I Am Writing to Bring to Your Attention an Important

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

05-11-2019 Gotter Eve.Indd

Synopsis Prologue Mythical times. At night in the mountains, the three Norns, daughters of Erda, weave the rope of destiny. They tell how Wotan ordered the World Ash Tree, from which his spear was once cut, to be felled and its wood piled around Valhalla. The burning of the pyre will mark the end of the old order. Suddenly, the rope breaks. Their wisdom ended, the Norns descend into the earth. Dawn breaks on the Valkyries’ rock, and Siegfried and Brünnhilde emerge. Having cast protective spells on Siegfried, Brünnhilde sends him into the world to do heroic deeds. As a pledge of his love, Siegfried gives her the ring that he took from the dragon Fafner, and she offers her horse, Grane, in return. Siegfried sets off on his travels. Act I In the hall of the Gibichungs on the banks of the Rhine, Hagen advises his half- siblings, Gunther and Gutrune, to strengthen their rule through marriage. He suggests Brünnhilde as Gunther’s bride and Siegfried as Gutrune’s husband. Since only the strongest hero can pass through the fire on Brünnhilde’s rock, Hagen proposes a plan: A potion will make Siegfried forget Brünnhilde and fall in love with Gutrune. To win her, he will claim Brünnhilde for Gunther. When Siegfried’s horn is heard from the river, Hagen calls him ashore. Gutrune offers him the potion. Siegfried drinks and immediately confesses his love for her.Ð When Gunther describes the perils of winning his chosen bride, Siegfried offers to use the Tarnhelm to transform himself into Gunther. -

SM358-Voyager Quartett-Book-Lay06.Indd

WAGNER MAHLER BOTEN DER LIEBE VOYAGER QUARTET TRANSCRIPTED AND RECOMPOSED BY ANDREAS HÖRICHT RICHARD WAGNER TRISTAN UND ISOLDE 01 Vorspiel 9:53 WESENDONCK 02 I Der Engel 3:44 03 II Stehe still! 4:35 04 III Im Treibhaus 5:30 05 IV Schmerzen 2:25 06 V Träume 4:51 GUSTAV MAHLER STREICHQUARTETT NR. 1.0, A-MOLL 07 I Moderato – Allegro 12:36 08 II Adagietto 11:46 09 III Adagio 8:21 10 IV Allegro 4:10 Total Time: 67:58 2 3 So geht das Voyager Quartet auf Seelenwanderung, überbringt klingende BOTEN DER LIEBE An Alma, Mathilde und Isolde Liebesbriefe, verschlüsselte Botschaften und geheime Nachrichten. Ein Psychogramm in betörenden Tönen, recomposed für Streichquartett, dem Was soll man nach der Transkription der „Winterreise“ als Nächstes tun? Ein Medium für spirituelle Botschaften. Die Musik erhält hier den Vorrang, den Streichquartett von Richard Wagner oder Gustav Mahler? Hat sich die Musikwelt Schopenhauer ihr zugemessen haben wollte, nämlich „reine Musik solle das nicht schon immer gewünscht? Geheimnisse künden, die sonst keiner wissen und sagen kann.“ Vor einigen Jahren spielte das Voyager Quartet im Rahmen der Bayreuther Andreas Höricht Festspiele ein Konzert in der Villa Wahnfried. Der Ort faszinierte uns über die Maßen und so war ein erster Eckpunkt gesetzt. Die Inspiration kam dann „Man ist sozusagen selbst nur ein Instrument, auf dem das Universum spielt.“ wieder durch Franz Schubert. In seinem Lied „Die Sterne“ werden eben diese Gustav Mahler als „Bothen der Liebe“ besungen. So fügte es sich, dass das Voyager Quartet, „Frauen sind die Musik des Lebens.“ das sich ja auf Reisen in Raum und Zeit begibt, hier musikalische Botschaften Richard Wagner versendet, nämlich Botschaften der Liebe von Komponisten an ihre Musen. -

The Ring Sample Lesson Plan: Wagner and Women **Please Note That This Lesson Works Best Post-Show

The Ring Sample Lesson Plan: Wagner and Women **Please note that this lesson works best post-show Educator should choose which female character to focus on based on the opera(s) the group has attended. See below for the list of female characters in each opera: Das Rheingold: Fricka, Erda, Freia Die Walküre: Brunhilde, Sieglinde, Fricka Siegfried: Brunhilde, Erda Götterdämmerung: Brunhilde, Gutrune GRADE LEVELS 6-12 TIMING 1-2 periods PRIOR KNOWLEDGE Educator should be somewhat familiar with the female characters of the Ring AIM OF LESSON Compare and contrast the actual women in Wagner’s life to the female characters he created in the Ring OBJECTIVES To explore the female characters in the Ring by studying Wagner’s relationship with the women in his life CURRICULAR Language Arts CONNECTIONS History and Social Studies MATERIALS Computer and internet access. Some preliminary resources listed below: Brunhilde in the “Ring”: (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Brynhildr#Wagner's_%22Ring%22_cycle) First wife Minna Planer: (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Minna_Planer) o Themes: turbulence, infidelity, frustration Mistress Mathilde Wesendonck: (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mathilde_Wesendonck) o Themes: infatuation, deep romantic attachment that’s doomed, unrequited love Second wife Cosima Wagner: (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cosima_Wagner) o Themes: devotion to Wagner and his works; Wagner’s muse Wagner’s relationship with his mother: (https://www.thefamouspeople.com/profiles/richard-wagner-392.php) o Theme: mistrust NATIONAL CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.RL.7.9 STANDARDS/ Compare and contrast a fictional portrayal of a time, place, or character and a STATE STANDARDS historical account of the same period as a means of understanding how authors of fiction use or alter history. -

The Bayreuth Festspielhaus: the Metaphysical Manifestation of Wagner's Der Ring Des Nibelungen Matthew Timmermans University of Ottawa

Nota Bene: Canadian Undergraduate Journal of Musicology Volume 8 | Issue 1 Article 6 The Bayreuth Festspielhaus: The Metaphysical Manifestation of Wagner's Der Ring des Nibelungen Matthew Timmermans University of Ottawa Recommended Citation Timmermans, Matthew (2015) "The Bayreuth Festspielhaus: The Metaphysical Manifestation of Wagner's Der Ring des Nibelungen," Nota Bene: Canadian Undergraduate Journal of Musicology: Vol. 8: Iss. 1, Article 6. The Bayreuth Festspielhaus: The Metaphysical Manifestation of Wagner's Der Ring des Nibelungen Abstract This essay explores how the architectural design of the Bayreuth Festspielhaus effects the performance of Wagner’s later operas, specifically Der Ring des Nibelungen. Contrary to Wagner’s theoretical writings, which advocate equality among the various facets of operatic production (Gesamtkuntswerk), I argue that Wagner’s architectural design elevates music above these other art forms. The evidence lies within the unique architecture of the house, which Wagner constructed to realize his operatic vision. An old conception of Wagnerian performance advocated by Cosima Wagner—in interviews and letters—was consciously left by Richard Wagner. However, I juxtapose this with Daniel Barenboim’s modern interpretation, which suggests that Wagner unconsciously, or by a Will beyond himself, created Bayreuth as more than the legacy he passed on. The juxtaposition parallels the revolutionary nature of Wagner’s ideas embedded in Bayreuth’s architecture. To underscore this revolution, I briefly outline Wagner’s philosophical development, specifically the ideas he extracted from the works of Ludwig Feuerbach and Arthur Schopenhauer, further defining the focus of Wagner’s composition and performance of the music. The analysis thereby challenges the prevailing belief that Wagner intended Bayreuth and Der Ring des Nibelungen, the opera which inspired the house’s inception, to embody Gesamtkunstwerk; instead, these creations internalize the drama, allowing the music to reign supreme. -

WAGNER and the VOLSUNGS None of Wagner’S Works Is More Closely Linked with Old Norse, and More Especially Old Icelandic, Culture

WAGNER AND THE VOLSUNGS None of Wagner’s works is more closely linked with Old Norse, and more especially Old Icelandic, culture. It would be carrying coals to Newcastle if I tried to go further into the significance of the incom- parable eddic poems. I will just mention that on my first visit to Iceland I was allowed to gaze on the actual manuscript, even to leaf through it . It is worth noting that Richard Wagner possessed in his library the same Icelandic–German dictionary that is still used today. His copy bears clear signs of use. This also bears witness to his search for the meaning and essence of the genuinely mythical, its very foundation. Wolfgang Wagner Introduction to the program of the production of the Ring in Reykjavik, 1994 Selma Gu›mundsdóttir, president of Richard-Wagner-Félagi› á Íslandi, pre- senting Wolfgang Wagner with a facsimile edition of the Codex Regius of the Poetic Edda on his eightieth birthday in Bayreuth, August 1999. Árni Björnsson Wagner and the Volsungs Icelandic Sources of Der Ring des Nibelungen Viking Society for Northern Research University College London 2003 © Árni Björnsson ISBN 978 0 903521 55 0 The cover illustration is of the eruption of Krafla, January 1981 (Photograph: Ómar Ragnarsson), and Wagner in 1871 (after an oil painting by Franz von Lenbach; cf. p. 51). Cover design by Augl‡singastofa Skaparans, Reykjavík. Printed by Short Run Press Limited, Exeter CONTENTS PREFACE ............................................................................................ 6 INTRODUCTION ............................................................................... 7 BRIEF BIOGRAPHY OF RICHARD WAGNER ............................ 17 CHRONOLOGY ............................................................................... 64 DEVELOPMENT OF GERMAN NATIONAL CONSCIOUSNESS ..68 ICELANDIC STUDIES IN GERMANY ......................................... -

SOMMARIO Una Premessa Sul Puro Umano E Wagner Oggi Il Puro

SOMMARIO L'ONTOLOGIA DELL'UMANO Una premessa sul puro umano e Wagner oggi Il puro umano VII L'intreccio XVII Wagner oggi XX RICHARD WAGNER LA POETICA DEL PURO UMANO A PARIGI: BERLIOZ, LISZT, WAGNER Un intreccio affascinante La malinconia dell'essere: la poetica della Romantik 3 La cultura musicale nella Parigi degli anni Trenta, una fìtta trama di relazioni 16 Berlioz, emancipazione del parametro timbrico 33 Liszt e Chopin, ricerca strumentale e compositiva 45 Wagner, «Un musicista tedesco a Parigi» 71 IN GERMANIA, LA POETICA DEL PURO UMANO Trame di passione Le composizioni strumentali giovanili 101 Mendelssohn e gli Schumann, incomprensioni e polemiche 123 I primi abbozzi teatrali e Le fate 133 II divieto d'amare, «Canto, canto e ancora canto, o tedeschi!» 144 Rienzi, «Armi», «Bandiere», «Onore», «Libertà» 153 L'Olandese volante, «Ah! Superbo oceano!» 170 http://d-nb.info/1024420035 Tannhàuser, «Potete voi tutti scoprirmi la natura dell'amore?» 196 Lohengrin, «Mai non dovrai domandarmi» 222 I Wibelunghi, i moti rivoluzionari, L'arte e la rivoluzione, Gesù di Nazareth 2S3 SCHOPENHAUER E LE «DIVINE PARTITURE» Gli scritti e i capolavori L'arrivo in Svizzera, Wieland il fabbro, Liszt, i brani pianistici, Berlioz 269 L'opera d'arte dell'avvenire, Il giudaismo nella musica, Opera e dramma, Una comunicazione ai miei amici 290 Schopenhauer, «Mi sentii subito profondamente attratto» 314 Wesendonck-Lieder, Parigi, Rossini, Ludwig II 322 Tristan, «Naufragare / affondare / inconsapevolmente / suprema letizia!» 359 Il libro bruno, La mia vita, Il -

Wagner Intoxication

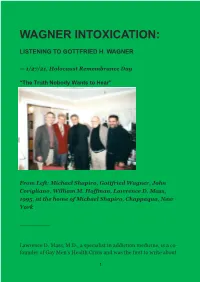

WAGNER INTOXICATION: LISTENING TO GOTTFRIED H. WAGNER — 1/27/21, Holocaust Remembrance Day “The Truth Nobody Wants to Hear” From Left: Michael Shapiro, Gottfried Wagner, John Corigliano, William M. Hoffman, Lawrence D. Mass, 1995, at the home of Michael Shapiro, Chappaqua, New York _________ Lawrence D. Mass, M.D., a specialist in addiction medicine, is a co- founder of Gay Men’s Health Crisis and was the first to write about 1 AIDS for the press. He is the author of We Must Love One Another or Die: The Life and Legacies of Larry Kramer. He is completing On The Future of Wagnerism, a sequel to his memoir, Confessions of a Jewish Wagnerite. For additional biographical information on Lawrence D. Mass, please see: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lawrence_D._Mass Larry Mass: For Gottfried Wagner, my work on Wagner, art and addiction struck an immediate chord of recognition. I was trying to describe what Gottfried has long referred to as “Wagner intoxication.” In fact, he thought this would make a good title for my book. The subtitle he suggested was taken from the title of his Foreword to my Confessions of a Jewish Wagnerite: “Redemption from Wagner the redeemer: some introductory thoughts on Wagner’s anti- semitism.” The meaning of this phrase, “redemption from the redeemer,” taken from Nietzsche, is discussed in the interview with Gottfried that follows these reflections. Like me, Gottfried sees the world of Wagner appreciation as deeply affected by a cultish devotion that from its inception was cradling history’s most irrational and extremist mass-psychological movement. -

SCHOLARLY PROGRAM NOTES of SELECTED WORKS by LUDWIG VAN BEETHOVEN, RICHARD WAGNER, and JAMES STEPHENSON III Jeffrey Y

Southern Illinois University Carbondale OpenSIUC Research Papers Graduate School 5-2017 SCHOLARLY PROGRAM NOTES OF SELECTED WORKS BY LUDWIG VAN BEETHOVEN, RICHARD WAGNER, AND JAMES STEPHENSON III Jeffrey Y. Chow Southern Illinois University Carbondale, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://opensiuc.lib.siu.edu/gs_rp CLOSING REMARKS In selecting music for this program, the works had instrumentation that fit with our ensemble, the Southern Illinois Sinfonietta, yet covering three major periods of music over just a little more than the past couple of centuries. As composers write more and more for a chamber ensemble like the musicians I have worked with to carry out this performance, it becomes more and more idiomatic for conductors like myself to explore their other compositions for orchestra, both small and large. Having performed my recital with musicians from both the within the Southern Illinois University Carbondale School of Music core and from the outside, this entire community has helped shaped my studies & my work as a graduate student here at Southern Illinois University Carbondale, bringing it all to a glorious end. Recommended Citation Chow, Jeffrey Y. "SCHOLARLY PROGRAM NOTES OF SELECTED WORKS BY LUDWIG VAN BEETHOVEN, RICHARD WAGNER, AND JAMES STEPHENSON III." (May 2017). This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at OpenSIUC. It has been accepted for inclusion in Research Papers by an authorized administrator of OpenSIUC. For more information, please contact [email protected]. -

Wagner in the "Cult of Art in Nazi Germany"

Loyola University Chicago Loyola eCommons History: Faculty Publications and Other Works Faculty Publications 2-1-2013 Wagner in the "Cult of Art in Nazi Germany" David B. Dennis Loyola University Chicago, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://ecommons.luc.edu/history_facpubs Part of the History Commons Author Manuscript This is a pre-publication author manuscript of the final, published article. Recommended Citation Dennis, David B.. Wagner in the "Cult of Art in Nazi Germany". WWW2013: Wagner World Wide (marking the Wagner’s bicentennial) at the University of South Carolina, Columbia, SC, , : , 2013. Retrieved from Loyola eCommons, History: Faculty Publications and Other Works, This Conference Proceeding is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Publications at Loyola eCommons. It has been accepted for inclusion in History: Faculty Publications and Other Works by an authorized administrator of Loyola eCommons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 License. © David B. Dennis 2013 Richard Wagner in the “Cult of Art” of Nazi Germany A Paper for the Wagner Worldwide 2013 Conference University of South Carolina, Columbia, SC January 30-February 2, 2013 David B. Dennis Professor of History Loyola University Chicago In his book on aesthetics and Nazi politics, translated in 2004 as The Cult of Art in Nazi Germany, Eric Michaud, Director of Studies at the École des Hautes Études en Sciences Sociales in Paris, wrote that National Socialist attention to the arts was intended “to present the broken [German] Volk with an image of its ‘eternal Geist’ and to hold up to it a mirror capable of restoring to it the strength to love itself.” 1 I came upon this, among other ideas of Michaud, when preparing the conceptual framework for my own book, Inhumanities: Nazi Interpretations of Western Culture, just released by Cambridge University Press. -

Read Book Wagner on Conducting

WAGNER ON CONDUCTING PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Richard Wagner,Edward Dannreuther | 118 pages | 01 Mar 1989 | Dover Publications Inc. | 9780486259321 | English | New York, United States Richard Wagner | Biography, Compositions, Operas, & Facts | Britannica Impulsive and self-willed, he was a negligent scholar at the Kreuzschule, Dresden , and the Nicholaischule, Leipzig. He frequented concerts, however, taught himself the piano and composition , and read the plays of Shakespeare, Goethe, and Schiller. Wagner, attracted by the glamour of student life, enrolled at Leipzig University , but as an adjunct with inferior privileges, since he had not completed his preparatory schooling. Although he lived wildly, he applied himself earnestly to composition. Because of his impatience with all academic techniques, he spent a mere six months acquiring a groundwork with Theodor Weinlig, cantor of the Thomasschule; but his real schooling was a close personal study of the scores of the masters, notably the quartets and symphonies of Beethoven. He failed to get the opera produced at Leipzig and became conductor to a provincial theatrical troupe from Magdeburg , having fallen in love with one of the actresses of the troupe, Wilhelmine Minna Planer, whom he married in In , fleeing from his creditors, he decided to put into operation his long-cherished plan to win renown in Paris, but his three years in Paris were calamitous. Living with a colony of poor German artists, he staved off starvation by means of musical journalism and hackwork. In , aged 29, he gladly returned to Dresden, where Rienzi was triumphantly performed on October The next year The Flying Dutchman produced at Dresden, January 2, was less successful, since the audience expected a work in the French-Italian tradition similar to Rienzi and was puzzled by the innovative way the new opera integrated the music with the dramatic content. -

Richard Wagner German Romantic Era Opera Composer (1813-1883)

Hey Kids, Meet Richard Wagner German Romantic Era Opera Composer (1813-1883) Richard Wagner was born in Leipzig, Germany, on May 22, 1813. He was the ninth son of Carl Friedrich Wagner and Johanna Rosine. Richard's father died of typhus six months after his birth. His mother then married painter, actor, and poet, Ludwig Geyer, and the family moved to Dresden. Richard took an interest in the plays in which his step- father performed, and Richard sometimes even partici- pated in the plays alongside of him. In late 1820, Richard received some piano instruction from a Latin teacher. As a teen, Richard's teacher said that he would "torture the piano in a most abominable fashion." Despite what his teacher thought, Richard enjoyed playing the piano, and began to compose music as a teenager. In 1831, he attended Leipzig University. He was impacted greatly by famous musicians, such as Beethoven, Mozart, and Wilhelmine Schröder-Devrient. In 1833 Wagner became a choir master in Würzburg, Germany. Within a year of obtaining this position, Wagner composed his first opera, Die Feen (The Fairies). This opera was not performed until after his death. Between 1857-1864, he wrote the opera Tristan and Isolde, a tragic love story. Many musi- cians consider Tristan and Isolde to be the beginning of modern classical music. Because of Wagner's strong political views and his poor money management, Wagner had to move often, moving to Russia, France, Switzerland, and then back to Germany. Even though his life was turbulent, he produced some of his most famous works during this time. -

Walk of Wagner in Bayreuth

heute 1883 1872 Richard Wagner dirigiert am 22.5.1872 Beethovens 9. Synphonie G. Bechstein, 1876 Der Trauerzug mit der Leiche Richard Wagners Weltkulturerbe Opernhaus Festspielhaus am Grünen Hügel Ankunft am BahnhofRichard-Wagner-Stationen in Bayreuth Tourist-Information 1860 wurde hier schon im Beisein von König Maximilian II. von Bayern Richard Auf der ganzen Welt gibt es kein Opernhaus, das dem Werk nur eines Als Wagner 1872 mit seiner Familie nach Bayreuth zog, stand hier noch der Festspielhaus Richard-Wagner-Museum Tourist-Information Wagners Tannhäuser aufgeführt. 1870 wurde es Wagner – er lebte damals Künstlers gewidmet wäre. Für diesen kulturpolitischen Traum hat Richard alte Bahnhof. 1876 – im Jahr der ersten Festspiele – waren die geplante zwei- Grüner Hügel Haus Wahnfried. Träger: & Bayreuth Shop noch in Tribschen in der Schweiz und war auf der Suche nach einem Ort für Wagner gekämpft in einer Zeit, als das Urheberrecht noch in den Anfängen te Eisenbahnverbindung nach Nürnberg und der neue Bau erst in Arbeit. Richard-Wagner-Stiftung Bayreuth Opernstraße 22 / 95444 Bayreuth seine eigenen Festspiele – von Dirigent Hans Richter wegen seiner überdimen- steckte, an anderen Theatern Aufführungen fast ohne Proben stattfanden, 1879 war er endlich vollendet und Cosima konnte am 23. September in ihr Leitung: Dr. Sven Friedrich Tel. 0921-885 88 sional großen Bühne gerühmt. Als Richard und Cosima 1871 den Bau besichtig- die Sänger schlecht – und schon gar nicht schauspielerisch – ausgebildet waren, Tagebuch schreiben: „Im neuen Bahnhof, der R. viele Freude macht, Bier Wegen umfassender Sanierung, Mail: [email protected] ten, stellten sie allerdings fest, dass die spätbarocke Ausstattung mit Apoll und Musiker ohne soziale Absicherung im Range von Dienstboten entlohnt wur- getrunken.