The Semantic and Syntactic Ingredients of Greek Dish Names

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Soup Appetizers Lunch Entrees

SOUP LUNCH ENTREES CHICKEN AVGOLEMONO . .3.95 Served until 3:30pm A traditional soup made with a broth of lemon, egg and chicken. All entrees served with a salad and warm bread. Rice pilaf available with all entrees for an additional. 1.75 • Extra yogurt .50 each. APPETIZERS SOUVLAKI LUNCHEON PLATE 7.95 A skewer of our Greek Shish-ka-bob. If you prefer, your Souvlaki can be prepared HOT ITEMS with all lamb for an additional charge of 1.50 per skewer. CALAMARAKIA TIGANITA 10.95 THRACIAN CHICKEN LUNCHEON PLATE 7.95 Not even in the Greek Isles will you find a dish like this! Baby squid dipped in Symeon’s A single breast of our marinated, charbroiled chicken. original batter, deep-fried to a crisp golden brown and sprinkled with Symeon’s Seasonings. LEMON-ROSEMARY CHICKEN 7.95 MELITZANES TIGANITES 7.95 A low cholesterol and low sodium version of our Thracian chicken. Fresh eggplant, deep fried and sprinkled with Symeon’s seasonings. Salad served with a salt free dressing and without feta cheese. KREATOPITA 2.95 CHICKEN FLORENTINE 9.95 Ground beef, sautéed onions and feta cheese wedged between layers of buttery filo pastry Our chicken breast is stuffed with spinach and feta cheese, topped with Kasseri cheese and baked to a golden brown. and a hint of wine, then baked to a golden brown. 4941 Commercial Drive SPANAKOTIROPITA 2.95 CHICKEN KA-BOB 10.95 Yorkville, New York 13492 Spinach and feta cheese wedged between layers of buttery filo pastry and baked to a golden brown. -

Super Hot Specials!

SUPER HOT SPECIALS! Check our weekly specials at WWW.BAIZMARKET.COM FOR ALL OF YOUR DOMESTIC & INTERNATIONAL FOODS! BAKERY, DELI, GROCERY, FRESH MEATS, PRODUCE, & MEDITERRANEAN RESTAURANT THREE LOCATIONS TO BETTER SERVE YOU 602-603-1049 602-252-8996 480-718-9227 VALID ONLY AT THIS LOCATION 8030 N. 27th Ave 523 N. 20thSt. 1858 W. Baseline Rd. START 09/12/2019 END 09/18/2019 Phoenix, AZ 85051 Phoenix, AZ 85006 Mesa AZ, 85202 Mon.-Sat. 9:00am – 9:00pm • Sun. 9:00am – 8:00pm Mon.-Sat. 9:00am – 6:30pm • Sun. 9:00am – 6:00pm Mon.-Sat. 9:00am – 9:00pm • Sun. 9:00am – 8:00pm ¢ ¢ $ Brown Onions Green Grapes 99lb 2 3 99 Romaine Lettuce pcs 1 lbs ¢ ¢ White Peach ¢ 69lb 69lb Cauliflower Yellow Peach 49lb Roma Tomatoes ¢ Large Granny ¢ American & $ 69 Smith Apples 49 Italian Parsley lb lb 4 1 Bunches FRESH FRESH FRESH Boneless Baby Lamb 49 Beef T-Bone Lamb 59 Chops Steak 79 5 lb 6 lb 6 lb حالل حالل HALAL HALAL FRESH FRESH FRESH Beef Short Lamb Burger Ribeye Ribs Patties 94 Steak 49 4 lb 7 lb 49 حالل حالل lb 4 HALAL HALAL FRESH FRESH FRESH Goat Meat Cut 74 Baby Lamb Breakfast Beef 99 Shoulder Steak 5 lb 4 lb 49 5 lb حالل HALAL حالل HALAL SERVICE DELI All Fresh Imported Olives & Feta Cheeses, Halal Cold Cut Meats, Fresh Nuts & Pastries! Chicago Touma 49 Blue 79 Greek Feta 49 Edam Cheese 4 lb Cheese 5 lb Cheese 3 lb Cheese 79 5 lb Kalamata Jumbo Olives Kasseri Cheese 79 Lappi 97 Monterey Jack 94 Karoun 5 lb Cheese 4 lb Cheese 2 lb 69 3 lb Halawa Plain 46 2 lb Provolone 97 Swiss 79 Danish Feta 99 Cheese 2 lb Cheese 4 lb Cheese 2 lb HALALحالل 99 69 3 ea -

Data Submission

Food Additives and Contaminants Part B – raw data submission Food Additives & Contaminants, Part B publishes surveillance data indicating the presence and levels of occurrence of designated food additives, residues and contaminants in foods and animal feed. Data using validated methods must meet stipulated quality standards to be acceptable and must be presented in a prescribed format for subsequent data-handling. This note describes the REQUIRED format for submission of data to enable easy and rapid entry onto the database. Entry will allow readers to access the original data set behind the paper and subscribers to the journal to download aggregated data sets across a range of papers where matrices and/or analytes are common. Food Additives & Contaminants, Part B has a restricted scope in terms of classes of food additives, residues and contaminants that are included, being based on a goal of covering those areas where there is a need to record surveillance data for the purposes of exposure and risk assessment. Accumulated data sets available from the database will assist in such analyses. The Sample spreadsheet This should contain one row for EVERY sample, including any samples which were analysed but no residues were found, if these are included in the final data set reported in the paper. Sample_id – this column is vital and should be used to give each sample a unique identifier. It may be simple, for example 1, 2, 3 .....n or contain a more complex textual string used by the original survey, for example something like “13547/27.6 AAC”. It does not matter how complex it is, as long as the same identifier is used to relate that sample to all the rows of results on the results spreadsheet for that sample. -

Product Catalog

Importers, Manufacturers & Distributors of Specialty Foods ATALO C MAY 2020 G www.krinos.com Importers, Manufacturers & Distributors of Specialty Foods 1750 Bathgate Ave. Bronx, NY 10457 Ph: (718) 729-9000 Atlanta | Chicago | New York ANTIPASTI . 17 APPETIZERS . 19 BEVERAGES . 34 BREADS . 26 CHEESE. 1 COFFEE & TEA. 32 CONFECTIONARY. 40 COOKING & BAKING . 37 DAIRY . 27 FISH . 28 HONEY. 11 JAMS & PRESERVES . 13 MEATS . 30 OILS & VINEGARS . 9 OLIVES . 5 PASTA, GRAINS, RICE & BEANS . 23 PEPPERS. 20 PHYLLO . 22 SEASONAL SPECIALTIES . 49 SNACKS . 39 SPREADS. 14 TAHINI. 16 VEGETABLES . 21 www.krinos.com CHEESE 20006 20005 20206 20102 20000 Athens Athens Krinos Krinos Krinos Feta Cheese - Domestic Feta Cheese - Domestic Feta Cheese - Domestic Feta Cheese - Domestic Feta Cheese - Domestic 8/4lb vac packs 5gal pail 2/8lb pails 10lb pail 5gal pail 21327 21325 21207 21306 21305 Krinos Krinos Krinos Krinos Krinos Dunavia Creamy Cheese Dunavia Creamy Cheese White Cheese - Bulgarian White Cheese - Bulgarian White Cheese - Bulgarian 12/400g tubs 8kg pail 12/14oz (400g) tubs 12/900g tubs 4/4lb tubs 21326 21313 21320 21334 21345 Krinos Krinos Krinos Krinos Krinos White Cheese - Bulgarian White Cheese - Bulgarian White Cheese - Bulgarian Greek Organic Feta Cheese Greek Organic Feta Cheese 2/4kg pails 6kg pail 5gal tin 12/5.3oz (150g) vac packs 12/14oz (400g) tubs 21202 21208 21206 21201 21205 Krinos Krinos Krinos Krinos Krinos Greek Feta Cheese Greek Feta Cheese Greek Feta Cheese Greek Feta Cheese Greek Feta Cheese 12/200g vac packs 2 x 6/250g wedges 12/14oz -

Zeus Grecian Island

Two locations serving you! Brighton • Lansing s h o w n w i t h to p p i ng & w hip ped cream 6 Authentic Taste • Real Value Carry Out Available great beginnings s a m p le WeAppetizer load this tantalizing Sampler platter with Platter mozzarella r pl cheese stix, cheese-stuffed jalapeño peppers and att er s golden chicken fingers. Great for sharing - 9.99 hown Saganaki Imported Kasseri cheese flamed tableside for a FChickenive tender Fingersbreaded chicken traditional Greek celebration of food. Opa! breast strips - 5.99 Served with fresh pita - 6.99 Mozzarella Cheese Stix (6) - 4.99 - 4.99 Zeus’ Chili Fry Supreme Fried Mushrooms A platter of fries, our chili sauce, shredded - 4.99 cheddar cheese, lettuce, tomatoes and onions. Fried Zucchini Sided with sour cream and salsa - 5.99 TheseWing meaty Dings lightly breaded wings are Stuffed Grape Leaves served plain or with your choice of Six stuffed grape leaves served buffalo or BBQ sauce chilled with fresh pita - 5.49 5 - 4.39 10 - 7.69 15 - 10.99 (6) - 4.99 AHummus middle Eastern delight! Ground chick peas with Stuffed Jalapeño Peppers tahini and select spices served with fresh pita - 5.49 FShrimpive succulent Cocktail chilled shrimp - 6.99 Get them deep-fried - 2.00 extra ATzatziki traditional blend of cucumber, garlic and yogurt served with fresh pita for dipping - 5.49 (Spanakopita) ASpinach Greek specialty! PieThin layers of filo pastry ThickOnion cut, Rings hand-battered and golden fried - 3.69 filled with garden fresh spinach, feta cheese and special seasonings. -

AMADA ROOM SERVICE.Pdf

Room service Menu Breakfast / Frühstück / Πρόγευμα Served from 7.00 until 11.00 Serviert von 7.00 bis 11.00 Uhr Σερβίρεται από τις 7.00 έως 11.00 π.μ. Kindly call “Guest Services” to place your order Wählen Sie bitte die “Guest Services” Παρακαλώ πολύ καλέστε το “Guest Services” Continental “plus” Breakfast Bakery basket Dear valuable Guest if you have any special request Bread rolls, toasted bread, Croissant and Danish pastries Served with Butter, marmalade and honey Choice of cereals Corn flakes, Muesli, All Bran Fresh Fruit salad and Greek Yogurt A hard-boiled egg and freshly squeezed Orange juice Coffee or Tea with milk €28,00c Continental Plus Frühstück Brotkorb Brötchen, Toastbrot, Croissant und Dänische Pasteten Serviert mit Butter, Marmelade und Honig Auswahl an Frühstückscerealien Cornflakes, Müsli, All Bran Frischer Obstsalat und Griechischer Joghurt Ein hart gekochtes Ei und frisch gepresster Orangensaft Kaffee oder Tee mit Milch €28,00c Ευρωπαϊκό “Plus” πρόγευμα Καλαθάκι με αρτοσκευάσματα ψωμάκι, ψωμί του τοστ, κρουασάν και Δανέζικα γλυκά Σερβίρεται με βούτυρο, μαρμελάδα και μέλι Επιλογή δημητριακών Νιφάδες καλαμποκιού, Μούσλι, Δημητρικά ολικής άλεσης Φρέσκια φρουτοσαλάτα και στραγγιστό γιαούρτι Ένα βραστό σφιχτό αυγό και φρέσκο χυμό πορτοκαλιού Καφές ή τσάι με γάλα €28,00c “A la Carte Breakfast Choices” Organic Eggs Fried | Omelette | Scrambled Spiegeleier | Omelett | Rührei Τηγανητά | Ομελέτα | Στραπατσάδα €12,50c Omelette Three Eggs | Vegetables | Cold Cuts | Cheese Drei Eier | Gemüse | Aufschnitt | Käse Τρία Αυγά | Λαχανικά -

Take-Out Menu & Family Meal Deals

PASTAS Casseroles Served with a Dinner Salad (Kalamata olives are NOT pitted) and Seasonal Vegetables All Casseroles are Served with a Dinner Salad (Kalamata Olives are NOT Pitted) SMALL LARGE and Seasonal Vegetables PAPAPAVLO’S PASTA (ADD 6 OZ. CHICKEN BREAST $4.00) .......... $16.95 ...$20.95 SPANAKOPITA ..................................................................................................... $17.50 Penne Prepared Perfectly with Butter, Garlic and Parmesan Cheese Our Traditional Spinach Casserole of Fresh Spinach, Green Onions and Feta Baked in a Crispy Filo Pastry MEAT PASTA ........................................................................................ $18.95 ...$23.95 PASTITSIO ............................................................................................................. $20.95 Papapavlo’s Pasta Flavored With Mushrooms, Onions, Rosemary, Stewed Tomatoes Very Lean Beef Sautéed, Seasoned and Layered with Long, Tubular Macaroni and Baked in a Filo Pastry and Garlic, Topped with Parmesan Cheese MOUSSAKA ........................................................................................................... $21.95 GRILLED VEGETABLE PASTA (VEGAN UPON REQUEST) .......... $17.95 ...$22.95 Thinly Sliced Sautéed Eggplant and Russet Potatoes Layered Among a Delicious Blend of Hearty Seasoned Grilled Red and Green Bell Peppers, Pesto, Green Zucchini, Mushrooms & Eggplant Served Over Linguine Ground Beef, then Topped with a Creamy, yet Firm Béchamel Sauce and Baked then Tossed in a One of a Kind Roasted -

Meze Platter for Two (Veg) 34 Hummus, Tzatziki, Dolma, Falafel, Tahini, Spanakopita, Feta Cheese, and Greek Olives

MEZÉ’S Add fresh vegetable slices 3 HUMMUS (GF,VEG) 8 CALAMARI 11 Garbanzo beans, sesame paste (tahini), garlic, and Lightly breaded and golden fried squid with spicy lemon juice. Served with warm pita tzatziki CILANTRO JALAPENO HUMMUS (GF, VEG) 8 LAMB CHOPS (GF) 14 Served with warm pita Grilled lamb chops f inished with latho lemono TOMATO BASIL HUMMUS (GF, VEG) 8 SOUVLAKIA (Greek Kabob) (GF) Hummus Contest winner. Served with warm pita CHICKEN 11 / FILET 13 Mini skewers of protein served with tzatziki and FIERY FETA (GF, VEG) 8 pita Feta cheese, roasted red pepper, and garlic. Served with warm pita FIERY FETA MAC’ N CHEESE (VEG) 11 Penne pasta, kasseri, cheddar, f irey feta, and pita BABA GHANOUSH (GF, VEG) 8 crumbs (add bacon 1) Grilled eggplant, tahini, garlic, and lemon juice. Served with warm pita SPANAKOPITA (VEG) 11 Puff pastry f illed with fresh spinach, leeks, TZATZIKI (GF, VEG) 8 feta cheese, mint, dill, and served with tzatziki Greek yogurt, cucumber, garlic, dill, and mint. Served with warm pita DOLMATHES (GF) 14 Grape leaves stuffed with ground sirloin, rice, mint, FETA & OLIVES (GF, VEG) 10 dill, with avgolemono sauce Rousas feta cheese and assorted Greek olives GARLIC MASHED POTATOES (GF, VEG) 7 DOLMA (GF, VEG) 11 Roasted garlic and mizithra cheese Rice, green onion, parsley, dill, garlic mixed and wrapped in grape leaves POTATOES LEMONATO (GF) 7 Fried potatoes tossed in lemon juice and fresh herbs FALAFEL (GF, VEG) 9 Chickpea croquet, served with tahini and pita MEZE FRIES (VEG) 9 Hand cut and tossed in garlic, fresh parsley, topped SAGANAKI (VEG) 16 with feta cheese Pan seared kasseri cheese, flambéed in Metaxa brandy GREEK QUESADILLA (VEG) 9 Pita bread, feta, kasseri, cheddar, bell peppers, SHRIMP & OUZO SAGANAKI (GF) 19 onion, and tomato. -

French Sheep's Milk Cheese, Esquirrou, Is World Champion

Volume 38 March 9, 2018 Number 8 French sheep’s milk cheese, Like us on Facebook and follow us on Twitter! Esquirrou, is World Champion A MADISON, Wis. — A hard First runner-up in the con- The World Championship Austria; Le Maréchal made sheep’s milk cheese called test, with a fi nal round score of Cheese Contest, initiated in by Fromagerie Le Maréchal INSIDE Esquirrou, made in France at 98.267, is Arzberger Ursteirer, a 1957, is the largest technical SA, Granges-Marnand, Vaud, Mauleon Fromagerie by Michel hard cow’s milk cheese aged in cheese, butter, and yogurt com- Switzerland; Sartori Reserve ✦ Guest column: Touyarou and imported by a silver mine and made by Franz petition in the world. A team Espresso BellaVitano made by ‘Prevention and control of Savencia Cheese USA of New Moestl and Team of Almenland of 56 internationally-renowned Mike Matucheski, Sartori Co., yeast and molds in cheese.’ Holland, Pennsylvania, has Stollenkäse in Passail, Austria. judges evaluated all entries over Antigo, Wisconsin; De Graafst- For details, see page 4. been named the 2018 World Mont Vully Bio — a raw milk the three-day competition. room Oud made by De Graaf- Champion Cheese. cheese washed with Pinot Noir In addition to the champion stroom, Bleskensgraaf, Zuid ✦ Partnership fi nalized Earning a score of 98.376 out wine and made by Ewald Scha- and two runners-up, the top 20 Holland, Netherlands; Cheb- for Michigan facility. of 100 in last night’s fi nal judging fer of Fromagerie Schafer in fi nalists of the contest include: rie made by Woolwich Dairy’s For details, see page 5. -

Soups and Salads Starters

SOUPS AND SALADS Soup of Yesterday Greek Village Salad Always better the next day. MKT The iconic salad of Greece with tomatoes, Kalamata olives, cucumber, feta, pickled Avgolemono Soup red onion, Greek olive oil, oregano, Classic chicken, egg and lemon with orzo 8.00 and red wine vinegar Sm 8.95 / Lg 15.50 Caesar Salad a la Greque Seasonal Salad 10.00 Grilled romaine spear with crispy chickpea croutons, shaved kasseri cheese, alici Add to Any Salad: Chicken 8.50 anchovy, and creamy lemon-tahini dressing 10.00 Lamb or Shrimp* 10.00 Steak or Salmon* 12.00 STARTERS Nikanos Fried Calamari Warm Olives With fried chickpeas, tomato, A mix of marinated Greek olives, feta, marinated cherry peppers, garlic, chickpeas, and herbs 8.50 and lemon vinaigrette 14.50 Spanakopita Grilled Octopus Traditional Greek spinach and feta pie 11.95 With a warm salad of haricot vert, new potatoes, cherry tomatoes, oil cured olives, Warm Eggplant Bruschetta fava, and preserved lemon vinaigrette MKT On grilled semolina bread 9.50 Steamed Maine Mussels Crispy Ikarian Style Zucchini Wheels With ouzo, tomatoes, fennel, garlic, With tzatziki 10.50 olive oil, and herbs 14.00 Dolmades Keftedes Traditional Greek stuffed grape leaves Lamb meatballs braised in tomato sauce with avgolemono sauce 10.00 with grated kasseri cheese 10.00 Traditional Dips and Spreads Saganaki Tzatziki, Hummus, Tiggie’s Red Bean, Flaming Kashkaval cheese with ouzo, (with grilled pita) toasted fennel seed, and grapes 11.95 4.50 for One / 12.00 for Three *Consuming raw or undercooked meats, poultry, seafood, shellfish, or eggs may increase your risk of foodborne illness. -

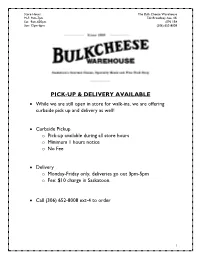

Pick-Up & Delivery Available

Store Hours: The Bulk Cheese Warehouse M-F: 9am-7pm 732 Broadway Ave, SK Sat: 9am-630pm S7N 1B4 Sun: 12pm-6pm (306) 652-8008 PICK-UP & DELIVERY AVAILABLE • While we are still open in store for walk-ins, we are offering curbside pick up and delivery as well! • Curbside Pickup o Pick-up available during all store hours o Minimum 1 hours notice o No Fee • Delivery o Monday-Friday only, deliveries go out 3pm-5pm o Fee: $10 charge in Saskatoon. • Call (306) 652-8008 ext-4 to order 1 Store Hours: The Bulk Cheese Warehouse M-F: 9am-7pm 732 Broadway Ave, SK Sat: 9am-630pm S7N 1B4 Sun: 12pm-6pm (306) 652-8008 PRODUCT LIST CHEESE FIRM CHEESES BLUE WASH RINDS • CHEDDAR (MED, 3, 4, 5, 8 YR) • SHROPSHIRE • OKA (CLASSIQUE, • MONTEREY JACK (REG/CHILI) • STILTON MUSHROOMS) • MUNSTER • GORGONZOLA • ST. PAULIN • HAVARTI (DILL, TOMATO, JALAPENO) • CAMBOZOLA • PORT SALUT • ASIAGO • ERMITE • TALLEGIO • MOZZA (REG, BUFFALO) • DANISH • ST. NECTAIRE • CURDS • HUNTSMAN • LIMBERGER • LATIN CHEESES (OAXACA, COTIJA, • ST. AGUR • SAINT MARCELLIN PANELA, FRESCO) • CHAUMES • RACLETTE (SWISS, OKA, FRENCH) SWISS BRIE STYLE GOUDA • EMMENTAL • CHATEAU DE • MILD, MEDIUM, AGED • GRUYERE BOURGOGNE • SPICED • COMTE • GRAND CRÈME • BEEMSTER 12 MONTH • FRERE JACQUES • ROITELET • BEEMSTER XO • MAASDAM • NORMANVILLE • BEEMSTER VLASKAAS • MONT VULLY • CAMEMBERT • OLD AMSTERDAM • TRUFFLE HEAVEN • SALMON DILL BRIE GREEK PARM FETA • HALLOUMI • GRANA PADANO • MACEDONIAN • SAGANAKI • REGGIANO • BULGARIAN • KEFALOTYRI • CROTONESE • SHEEP & GOAT • HALVA • CANADIAN • GOAT • KASSERI • ROMANO -

HUMMUS Tahini, Za'atar, Chickpeas, Pita 9 Add Crispy Lamb Or Grilled

HUMMUS OLIVES MEDITERRANEAN BRANZINO EACH 14 tahini, za’atar, chickpeas, pita 9 citrus marinated 5 “A LA PLANCHA” add crispy lamb or grilled chicken +5 spicy zhoug, SANGRIA add crispy mushrooms +3 HAMACHI CRUDO* lemon herbed labneh 38 wine, rum, citrus, chile, radish 12 seasonal fruit SMOKED EGGPLANT MESO’S BRICK CHICKEN pomegranate, za’atar, Mary’s Free Range chicken, KUFTA MEATBALLS POMEGRANATE MULE Aleppo, pita 9 lamb and beef, baby spinach, house spice blend, red yogurt vodka, pomegranate, pomegranate, pine nuts, tahini 17 half 24 | whole 44 RED BEET LABNEH lime, ginger beer bull’s blood beet greens, SAUTÉ ED PRAWNS BAHARAT NEW YORK STEAK hazelnut, pita 9 smoked paprika, 10 oz, tomato, onion, and herb salad 42 OLD FASHIONED garlic, sour grapes 23 whiskey, tea gum, bitters, LAMB SHANK ”TAGINE” citrus vanilla tincture HARISSA SEARED OCTOPUS ratatouille couscous, dried pear, confit potatoes, crispy Tuscan kale, golden raisins, dried cranberries FATTOUSH FIRE + SMOKE PALOMA herbed labneh 21 single 29 | double 55 cherry tomatoes, cucumbers, feta, house infused spicy tequila, pita croutons, sumac vinaigrette 15 mezcal, grapefruit, lime, CHARRED HALLOUMI TAGLIATELLE merguez sausage, piquillo peppers, Aleppo salt rim GOLDEN BEET SALAD honey, sesame seeds, tomato, kasseri cheese blend 24 arugula, goat cheese, mint, Maldon 16 candied hazelnuts, pear vinaigrette 14 MANHATTAN CAULIFLOWER STEAK whiskey, hibiscus infused vermouth, “A LA PLANCHA” tart cherry, bitters herb tarator, orange suprêmes, crispy quinoa, mint 12 PICKLED VEGETABLES GARDEN