Coping Strategies and Working Class Formation in Post-Soviet Ukraine

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

142-2019 Yukhnovskyi.Indd

Original Paper Journal of Forest Science, 66, 2020 (6): 252–263 https://doi.org/10.17221/142/2019-JFS Green space trends in small towns of Kyiv region according to EOS Land Viewer – a case study Vasyl Yukhnovskyi1*, Olha Zibtseva2 1Department of Forests Restoration and Meliorations, Forest Institute, National University of Life and Environmental Sciences of Ukraine, Kyiv 2Department of Landscape Architecture and Phytodesign, Forest Institute, National University of Life and Environmental Sciences of Ukraine, Kyiv *Corresponding author: [email protected] Citation: Yukhnovskyi V., Zibtseva O. (2020): Green space trends in small towns of Kyiv region according to EOS Land Viewer – a case study. J. For. Sci., 66: 252–263. Abstract: The state of ecological balance of cities is determined by the analysis of the qualitative composition of green space. The lack of green space inventory in small towns in the Kyiv region has prompted the use of express analysis provided by the EOS Land Viewer platform, which allows obtaining an instantaneous distribution of the urban and suburban territories by a number of vegetative indices and in recent years – by scene classification. The purpose of the study is to determine the current state and dynamics of the ratio of vegetation and built-up cover of the territories of small towns in Kyiv region with establishing the rating of towns by eco-balance of territories. The distribution of the territory of small towns by the most common vegetation index NDVI, as well as by S AVI, which is more suitable for areas with vegetation coverage of less than 30%, has been monitored. -

Public Evaluation of Environmental Policy in Ukraine

Public Council of All-Ukrainian Environmental NGOs under the aegis of the Ministry of the Environment and Natural Resources of Ukraine Organising Committee of Ukrainian Environmental NGOs for preparation to Fifth Pan-European Ministerial Conference "Environment for Europe" Public Evaluation of Environmental Policy in Ukraine Report of Ukrainian Environmental NGOs Кyiv — 2003 Public Evaluation of Environmental Policy in Ukraine. Report of Ukrainian Environmental NGOs. — Kyiv, 2003. — 139 pages The document is prepared by the Organising Committee of Ukrainian Environmental NGOs in the framework of the «Program of Measures for Preparation and Conduction of 5th Pan-European Ministerial Conference» «Environment for Europe» for 2002–2003» approved by the National Organising Committee of Ukraine. Preparation and publication of the report was done wit the support of: Regional Ecological Center - REC-Kyiv; Ministry of the Environment and Natural Resources of Ukraine; Milieukontakt Oost Europa in the framework of the project «Towards Kyiv-2003» with financial support of the Ministry of Territorial Planning, Construction and the Environment; UN office in Ukraine Contents Foreword . 1. Environmental Policy and Legislation . 1.1. Legislative Background of Environmental Policy . 1.2. Main State Documents Defining Environmental Policy . 1.3. Enforcement of Constitution of Ukraine . 1.4. Implementation of Environmental Legislation . 1.5. State of Ukrainian Legislation Reforming after Aarhus Convention Ratification . 1.6.Ukraine's Place in Transition towards Sustainable Development . 2. Environmental Management . 2.1. Activities of State Authorities . 2.2 Activities of State Control Authorities . 2.3. Environmental Monitoring System . 2.4. State Environmental Expertise . 2.5. Activities of Local Administrations in the Field of Environment . -

Journal of Forest Science

JOURNAL OF FOREST SCIENCE VOLUME 66 ISSUE 6 (On–line) ISSN 1805-935X Prague 2020 (Print) ISSN 1212-4834 Journal of Forest Science continuation of the journal Lesnictví-Forestry An international peer-reviewed journal published by the Czech Academy of Agricultural Sciences and supported by the Ministry of Agriculture of the Czech Republic Aims and scope: The journal publishes original results of basic and applied research from all fields of forestry related to European forest ecosystems. Papers are published in English. The journal is indexed in: • Agrindex of AGRIS/FAO database • BIOSIS Citation Index (Web of Science) • CAB Abstracts • CNKI (China National Knowledge Infrastructure) • CrossRef • Czech Agricultural and Food Bibliography • DOAJ (Directory of Open Access Journals) • EBSCO Academic Search • Elsevier Sciences Bibliographic Database • Emerging Sources Citation Index (Web of Science) • Google Scholar • J-Gate • Scopus • TOXLINE PLUS Periodicity: 12 issues per year, volume 66 appearing in 2020. Electronic open access Full papers from Vol. 49 (2003), instructions to authors and information on all journals edited by the Czech Academy of Agricultural Sciences are available on the website: https://www.agriculturejournals.cz/web/jfs/ Online manuscript submission Manuscripts must be written in English. All manuscripts must be submitted to the journal website (https://www. agriculturejournals.cz/web/jfs/). Authors are requested to submit the text, tables, and artwork in electronic form to this web address. It is to note that an editable file is required for production purposes, so please upload your text files as MS Word (.doc) files (pdf files will not be considered). Submissions are requested to include a cover letter (save as a separate file for upload), manuscript, tables (all as MS Word files – .doc), and photos with high (min 300 dpi) resolution (.jpg, .tiff and graphs as MS Excel file with data), as well as any ancillary materials. -

Ukr Glpm A2l 20150210.Pdf

22°0'0"E 23°0'0"E 24°0'0"E 25°0'0"E 26°0'0"E 27°0'0"E 28°0'0"E 29°0'0"E 30°0'0"E 31°0'0"E 32°0'0"E 33°0'0"E 34°0'0"E 35°0'0"E 36°0'0!!"E 37°0'0"E 38°0'0"E 39°0'0"E 40°0'0"E 41°0'0"E Michurinsk !! !! !! p E Yelets Lipetsk a !! Homyel N M BELARUS I ! g ! o ! ! ! N A n Brest " 0 Pinsk ' i 0 ° 2 5 n !Horodnya R !Shostka ! Pustohorod n ! Kursk K ! ! a Voronezh !Kuznetsovs'k ! ! l Hlukhiv ! P Lebedyn Krolevets' U Chernihiv ! VOLYNS'KA ! Staryy s ! c o RIVNENS'KA ! Oskol Ovruch Shestovytsya ! i Chornobyl'! CHERNIHIVS'KA ! ! Kovel' !Konotop t !Lublin ! ZHYTOMYRS'KA s RUSSIAN i SUMS'KA N !Nizhyn " 0 ' 0 g FEDERATION ° ! Korosten' Sumy 1 ! 5 o Volodymyr-Volyns'kyy !Kostopil' ! o L Luts'k ! ! !Romny Malyn ! l Borodyanka Novovolyns'k ! o !Rivne ! Novohrad-Volyns'kyy Vyshhorod !Pryluky Lebedyn Belgorod a (!o (!o ! ! !! ! Zdolbuniv ! ! r Sokal' Kiev ! Dubno Irpin Brovary e o ! Lokhvytsya ! \! Chervonohrad ! POLAND Netishyn o ! Boryspil' ! (! n Slavuta ! !Okhtyrka Vovchans'k ! o Yahotyn o ! (! ! ! Korostyshiv ! e Pyryatyn Zhytomyr ! ! ! G Brody ! Ozerne Vasylkiv KYYIVS'KA ! Fasti!v N ! Kremenets' Obukhiv " 0 ! ! ' Myrhorod Kharkiv 0 Lubny ! o! ° Rzeszow Bila ! ! 0 o 5 L'VIVS'KA Berdychiv ! Tserkva Uzyn Korotych (!o Beregovoye ! ! ! ! ! ! ! o! o Kaniv Merefa Chuhuyiv Horodok (! Starokostyantyniv ! o o ! Kupjansk o L'viv Zolotonosha POLTAVS'KA ! ! Krasyliv ! Poltava ! ! Lozovaya Khmil'nyk ! ! Kupyansk-Uzlovoy ! Volochys'k ! Sambir Ternopil' ! ! o o Suprunovka (! Khmel'nyts'kyy ! ! ! Cherkasy KHARKIVS'KA Kalynivka o ! Krasnohrad ! (! Stebnyk o ! ! ! Ivanivka -

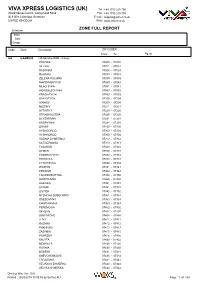

Viva Xpress Logistics (Uk)

VIVA XPRESS LOGISTICS (UK) Tel : +44 1753 210 700 World Xpress Centre, Galleymead Road Fax : +44 1753 210 709 SL3 0EN Colnbrook, Berkshire E-mail : [email protected] UNITED KINGDOM Web : www.vxlnet.co.uk Selection ZONE FULL REPORT Filter : Sort : Group : Code Zone Description ZIP CODES From To Agent UA UAAOD00 UA-Ukraine AOD - 4 days POLISKE 07000 - 07004 VILCHA 07011 - 07012 RADYNKA 07024 - 07024 RAHIVKA 07033 - 07033 ZELENA POLIANA 07035 - 07035 MAKSYMOVYCHI 07040 - 07040 MLACHIVKA 07041 - 07041 HORODESCHYNA 07053 - 07053 KRASIATYCHI 07053 - 07053 SLAVUTYCH 07100 - 07199 IVANKIV 07200 - 07204 MUSIIKY 07211 - 07211 DYTIATKY 07220 - 07220 STRAKHOLISSIA 07225 - 07225 OLYZARIVKA 07231 - 07231 KROPYVNIA 07234 - 07234 ORANE 07250 - 07250 VYSHGOROD 07300 - 07304 VYSHHOROD 07300 - 07304 RUDNIA DYMERSKA 07312 - 07312 KATIUZHANKA 07313 - 07313 TOLOKUN 07323 - 07323 DYMER 07330 - 07331 KOZAROVYCHI 07332 - 07332 HLIBOVKA 07333 - 07333 LYTVYNIVKA 07334 - 07334 ZHUKYN 07341 - 07341 PIRNOVE 07342 - 07342 TARASIVSCHYNA 07350 - 07350 HAVRYLIVKA 07350 - 07350 RAKIVKA 07351 - 07351 SYNIAK 07351 - 07351 LIUTIZH 07352 - 07352 NYZHCHA DUBECHNIA 07361 - 07361 OSESCHYNA 07363 - 07363 KHOTIANIVKA 07363 - 07363 PEREMOGA 07402 - 07402 SKYBYN 07407 - 07407 DIMYTROVE 07408 - 07408 LITKY 07411 - 07411 ROZHNY 07412 - 07412 PUKHIVKA 07413 - 07413 ZAZYMIA 07415 - 07415 POHREBY 07416 - 07416 KALYTA 07420 - 07422 MOKRETS 07425 - 07425 RUDNIA 07430 - 07430 BOBRYK 07431 - 07431 SHEVCHENKOVE 07434 - 07434 TARASIVKA 07441 - 07441 VELIKAYA DYMERKA 07442 - 07442 VELYKA -

The Ukrainian Weekly 2001, No.6

www.ukrweekly.com INSIDE:• Three deputies die in Ukraine — page 3. • St. Andrew’s Cathedral dedicates mosaic — page 7. • International film festival announces winners — page 12. Published by the Ukrainian National Association Inc., a fraternal non-profit association Vol. LXIX HE No.KRAINIAN 6 THE UKRAINIAN WEEKLY SUNDAY, FEBRUARY 11, 2001 EEKLY$1/$2 in Ukraine “Ukraine without Kuchma” protests intensify LastT of Ukraine’sU W by Roman Woronowycz Tu-160 bombers Kyiv Press Bureau KYIV – More than 10,000 people from many is dismantled regions of Ukraine marched through this capital by Roman Woronowycz city on February 6 waving the blue-yellow nation- Kyiv Press Bureau al emblem and chanting “Kuchma Out” and “Ukraine without Kuchma” before holding a mass PRYLUKY, Ukraine – Using a giant really at which leaders of various political stripes scissor-like tool, a U.S.-made Caterpillar called for the resignation of President Leonid excavator took all of 15 minutes on Kuchma. The politicians and demonstrators February 3 to snip through the metal skin charged that the president is involved in the disap- of the last of the Ukrainian-owned Tu-160 pearance of a Ukrainian journalist and the ensuing strategic nuclear bombers – in its time cover-up. probably the most feared piece of military The demonstration was marred by scuffles equipment in the old Soviet arsenal. between local militia, Communists who tried to As a crowd of some 100 military offi- disrupt the rally and paramilitary youth who took cials from the United States and Ukraine part in the protests, as well as an attack by about looked on, the nose of the aircraft, which 300 other youths from a heretofore unknown had already been gutted of salvageable organization called the Anarchist Syndicate on a equipment, first sagged forward and then, tent city re-erected in the city center. -

The Ukrainian National Association Forum

1NS1DE: ^ Ukraine marks solemn anniversary - page 3. " Plast U.S.A. holds biennial convention - page 5. e Organist from Ukraine goes on U.S. tour - page 15. THE UKRAINIAN WEEKLY Published by the Ukrainian National Association inc., a fraternal non-profit association vol. LXIX No. 49 THE UKRAINIAN WEEKLY SUNDAY, DECEMBER 9,2001 fyvS2 in Ukraine 10th anniversary of independence vote Ukraine begins census of population by Roman Woronowycz which the country belonged at the time. is marked with little fanfare in Ukraine Kyiv. Press Bureau That count showed Ukraine with a popu- lation of 51.45 million. by Roman Woronowycz anniversary of the national plebiscite held a KYiv - Ukraine began a head count Experts generally acknowledge that of its citizens on December 5 - the first Kyiv Press Bureau decade ago in which 84 percent of the the population in the country has one undertaken since the country Ukrainian population took part and nearly declined since then, with the latest esti- KYiv -Ukraine celebrated the 10th achieved independence and one that 91 percent answered in the affirmative to mates of the State Committee on anniversary of a national referendum that could show that the number of inhabi- the question on whether Ukraine should be Statistics putting the number of assured the country's independence with tants of the country is up to 5 percent an independent state, it was a result that put Ukrainians at just under 49 million. surpri singly little fanfare on December 1. lower than has been estimated. the final nail in the coffin of the Soviet Oleksander Osaulenko, director of the Perhaps the country was still recovering On the same day, national democratic Union. -

Of the Public Purchasing Announcernº11 (85) March 13, 2012

Bulletin ISSN: 2078–5178 of the public purchasing AnnouncerNº11 (85) March 13, 2012 Announcements of conducting procurement procedures � � � � � � � � � 2 Announcements of procurement procedures results � � � � � � � � � � � � 69 Urgently for publication � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � 141 Bulletin No�11 (85) March 13, 2012 Annoucements of conducting 06566 SOE “Donetsk Oblast Directorate on Liquidation procurement procedures of Unprofitable Coal–Mining Enterprises and Coal Refineries” (SOE “Donvuhlerestrukturyzatsiia”) Uspenskoho St., 86102 Makiivka, Donetsk Oblast 06541 SOE “Donetsk Coal and Energy Company” Nikulin Hryhorii Volodymyrovych 63 Artema St., 83001 Donetsk tel.: (06232) 9–33–02; Taran Viktor Mykolaiovych, Ahatii Volodymyr Valeriiovych, Martemianov Oleksandr tel./fax: (062) 302–81–61; Pavlovych, Tupchii Maryna Oleksandrivna e–mail: [email protected] tel.: (062) 345–79–68, 345–79–35, 382–61–67; Website of the Authorized agency which contains information on procurement: tel./fax: (062) 382–67–94; www.tender.me.gov.ua e–mail: [email protected] Procurement subject: physical liquidation of buildings and constructions Website of the Authorized agency which contains information on procurement: of mine “Petrovska” according to project on liquidation of www.tender.me.gov.ua “Petrovska” mine Website which contains additional information on procurement: www.duеk.dn.ua Supply/execution: Donetsk, mine “Petrovska”, May – August 2012 Procurement subject: code 02.01.1 – timber products (softwood mine prop), -

The Rank-And-File Perpetrators of 1932-1933 Famine in Ukraine and Their Representation in Cultural Memory

ʻIdle, Drunk and Good-for-Nothingʼ: The Rank-and-File Perpetrators of 1932-1933 Famine in Ukraine and Their Representation in Cultural Memory Daria Mattingly Robinson College July 2018 This dissertation is submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Preface This dissertation is the result of my own work and includes nothing that is the outcome of work done in collaboration. It is not substantially the same as any that I have submitted, or, is being concurrently submitted for a degree or other qualification at the University of Cambridge or any other University or any other University or similar institution except as declared in the Preface and specified in the text. I further state that no substantial part of my dissertation has already been submitted, or, is being concurrently submitted for any such degree, diploma or other qualification at the University of Cambridge or any other University or similar institution except as declared in the Preface and specified in the text. The word count of this dissertation is 77, 082. This falls within the word limit set by the Faculty of Modern and Medieval Languages Degree Committee. Abstract This dissertation examines identifiable traces of the perpetrators of the 1932-1933 famine in Ukraine, known as the Holodomor, and their representation in cultural memory. It shows that the men and women who facilitated the famine on the ground were predominantly ordinary people largely incongruous with the dominant image of the perpetrator in Ukrainian cultural memory. I organise this interdisciplinary study, which draws on a wide range of primary sources, including archival research at all levels – republican, oblast’, district, village and private, published and unpublished memoirs and, on one occasion, an interview with a perpetrator; major corpora of oral memory, post-memory and cultural texts – into two parts. -

Table of Contents Item Transcript

DIGITAL COLLECTIONS ITEM TRANSCRIPT Boris Goldshtein. Full, unedited interview, 2012 ID FL005.interview PERMALINK http://n2t.net/ark:/86084/b4707wq9b ITEM TYPE VIDEO ORIGINAL LANGUAGE RUSSIAN TABLE OF CONTENTS ITEM TRANSCRIPT ENGLISH TRANSLATION 2 CITATION & RIGHTS 11 2021 © BLAVATNIK ARCHIVE FOUNDATION PG 1/11 BLAVATNIKARCHIVE.ORG DIGITAL COLLECTIONS ITEM TRANSCRIPT Boris Goldshtein. Full, unedited interview, 2012 ID FL005.interview PERMALINK http://n2t.net/ark:/86084/b4707wq9b ITEM TYPE VIDEO ORIGINAL LANGUAGE RUSSIAN TRANSCRIPT ENGLISH TRANSLATION —Today is November 28, 2012. We are in Miami, meeting a veteran of the Great Patriotic War. Please introduce yourself and tell us where and when you were born. What sort of family did you grow up in, and what was life like before the war? My name is Boris Goldshtein and I was born on January 6, 1921, in the village of Popelnasta, Aleksandriya [Oleksandriia] District, Kirovograd [Kirovohrad] Oblast. My father was a blacksmith and my mother took care of the house. My older brother graduated from a technical school and then from an industrial college in Odessa [Odesa]. He was a battery commander during the war. He was killed. —What was his name? Pavel Samoylovich Goldshtein. I was conscripted into the armed forces in 1940. —I’m sorry, but I am going to interrupt you. Before the war, were there many Jews in your village? What were relations like between Jews and gentiles? Did the children make friends with one another? It was a large village, which sprawled out for about 4-5 kilometers. There were many Jews who lived there. We got along just fine with the locals. -

Annoucements of Conducting Procurement Procedures

Bulletin No�19 (93) May 08, 2012 Annoucements of conducting 11098 National University of the State Tax Service procurement procedures of Ukraine 31 K.Marksa St., 08201 Irpin, Kyiv Oblast Verzun Petro Mykolaiovych 11096 SOE “Horodnytsia Forestry” of Zhytomyr Oblast tel.: (04597) 6–04–72 Administration of Forestry Website of the Authorized agency which contains information on procurement: 5, 13–richchia Zhovtnia St., 11714 Horodnytsia Urban Settlement, Novohrad– www.tender.me.gov.ua Volynskyi Rayon, Zhytomyr Oblast Website which contains additional information on procurement: www.asta.edu.ua Metlytskyi Ivan Ivanovych Procurement subject: construction works on the object: “Reconstruction tel.: (04141) 6–52–46 of hostel of tax police faculty at 90 Sadova St., Irpin” – construction Website of the Authorized agency which contains information on procurement: works www.tender.me.gov.ua Supply/execution: 90 Sadova St., 08201 Irpin, Kyiv Oblast; till December 31, 2012 Procurement subject: code 60.10.2 – railway services in freight Procurement procedure: open tender transportation – 600 wagons Obtaining of competitive bidding documents: at the customer’s address, office 109 Supply/execution: at the customer’s address; June – December 2012 Submission: at the customer’s address, office 109 Procurement procedure: open tender 03.05.2012 10:00 Obtaining of competitive bidding documents: at the customer’s address, head’s Opening of tenders: 53 Sadova St., 08201 Irpin, Kyiv Oblast, office 104 office 03.05.2012 14:00 Submission: at the customer’s address, head’s office Tender security: not required 31.05.2012 10:00 Additional information: For additional information, please, call at Opening of tenders: at the customer’s address, head’s office tel.: (04597) 6–02–46 – Shpak Oksana Vitaliivna. -

The Ukrainian Weekly 1993

INSIDE: • Der Spiegel says Trawniki ID is a forgery — page 2. • Farewell letter of U.S. ambassador to Ukraine — page 6. • Part ii of interview with Sports Minister Valeriy Borzov — page 9. Vol. LXI No. 32 THE UKRAINIAN WEEKLY SUNDAY, AUGUST 8, 1993 50 cents Pennsy senator's amendment Federal court rules Demjanjuk seeks fair share of aid for Ul<rainemus t be allowed to re-enter US. by Xenia Ponomarenko assistance. JERSEY CITY, N.J. — After several awaiting an August 11 hearing on a peti UNA Washington Office In opening the mark-up. days of ups and downs, John Demjanjuk tion filed by Noam Federman, a leader of Subcommittee Chairman Sen. Paul and his family could celebrate yet anoth the far-right Kach Party, and Yizrael WASHINGTON — Sen. Harris Sarbanes (D-Md.) stated that controver er legal victory. On August 3, five days Yehezkeli, the Holocaust survivor who Wofford (D-Pa.) offered an amendment sial issues would be deferred for full after Mr. Demjanjuk was acquitted of all had served a two-year jail term for throw providing for a "fair share" of U.S. for committee consideration. After the sub Nazi war crimes charges by the Supreme ing acid into the face of Mr. Demjanjuk's eign assistance to Ukraine during the committee accepted the mark as pro Court of Israel, a federal court in lawyer, Yoram Sheftel. The petition Senate subcommittee consideration of posed by the chairman and the ranking Cincinnati ruled that the former argues that Mr. Demjanjuk should be the foreign aid authorization act. minority member, Sen.