The Hobkirk Family of Southdean

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Soils Round Jedburgh and Morebattle

DEPARTMENT OF AGRICULTURE FOR SCOTLAND MEMOIRS OF THE SOIL SURVEY OF GREAT BRITAIN SCOTLAND THE SOILS OF THE COUNTRY ROUND JEDBURGH & MOREBATTLE [SHEETS 17 & 181 BY J. W. MUIR, B.Sc.(Agric.), A.R.I.C., N.D.A., N.D.D. The Macaulay Institute for Soil Research ED INB URGH HER MAJESTY'S STATIONERY OFFICE '956 Crown copyright reserved Published by HER MAJESTY’SSTATIONERY OFFICE To be purchased from 13~Castle Street, Edinburgh 2 York House, Kingsway, Lond6n w.c.2 423 Oxford Street, London W.I P.O. Box 569, London S.E. I 109 St. Mary Street, Cardiff 39 King Street, Manchester 2 . Tower Lane, Bristol I 2 Edmund Street, Birmingham 3 80 Chichester Street, Belfast or through any bookseller Price &I 10s. od. net. Printed in Great Britain under the authority of Her Majesty’s Stationery Office. Text and half-tone plates printed by Pickering & Inglis Ltd., Glasgow. Colour inset printed by Pillans & Ylson Ltd., Edinburgh. PREFACE The soils of the country round Jedburgh and Morebattle (Sheets 17 and 18) were surveyed during the years 1949-53. The principal surveyors were Mr. J. W. Muir (1949-52), Mr. M. J. Mulcahy (1952) and Mr. J. M. Ragg (1953). The memoir has been written and edited by Mr. Muir. Various members of staff of the Macaulay Institute for Soil Research have contributed to this memoir; Dr. R. L. Mitchell wrote the section on Trace Elements, Dr. R. Hart the section on Minerals in Fine Sand Fractions, Dr. R. C. Mackenzie and Mr. W. A. Mitchell the section on Minerals in Clay Fractions and Mr. -

Cochran-Patrick, RW, Notes on the Scottish

PROCEEDINGS of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland Our full archive of freely accessible articles covering Scottish archaeology and history is available at http://archaeologydataservice.ac.uk/archives/view/psas/volumes.cfm National Museums Scotland Chambers Street, Edinburgh www.socantscot.org Charity No SC 010440 5 SCOTTISE NOTE22 TH N SO H MINTS. IV. E SCOTTISNOTETH N SO H MINTS. WR . Y COCHRAB . N PATRICK, ESQ., B.A., LL.B., F.S.A. SCOT. Any account which can now be given of the ancient Scottish mints must necessarily he very incomplete. The early records and registers are no longe scantw fe existencen ri ye th notice d an , s gatheree which n hca d fro Acte m th Parliamentf so othed an , r original sources, only serv shoo et w how imperfect our knowledge is. It may not, however, he altogether without interest to hring together something of what is still available, in the hope that other sources of information may yet be discovered. The history of the Scottish mints may be conveniently divided into two periods,—the first extendinge fro th earliese f mo th d ten timee th o st thirteenth century; the second beginning with the fourteenth century, and coming down to the close of the Scottish coinage at the Union. It must he remembered that there is little or no historical evidence availabl firse th tr perioefo d beyond wha s afforde i tcoine th y s b dthem - selvesconclusiony An . scome whicb regardino y et hma o t musgt i e b t a certain extent conjectures e liablmodified authentiy h ,an an o t e y b d c information whic stily e discoveredb lhma t I present. -

The Galashiels and Selkirk Almanac and Directory for 1898

UMBRELLAS Re-Covered in One Hour from 1/9 Upwards. All Kinds of Repairs Promptly Executed at J. R. FULTON'S Umbrella Ware- house, 51 HIGH STREET, Galashiels. *%\ TWENTIETH YEAR OF ISSUE. j?St masr Ok Galasbiels and Selkirk %•* Almanac and Directorp IFOIR, X898 Contains a Variety of Useful information, County Lists for Roxburgh and Selkirk, Local Institutions, and a Complete Trade Directory. Price, - - One Penny. PUBLISHED BY JOH3ST ZMZCQ-CTiEiE] INT, Proprietor of the "Scottish Border Record," LETTERPRESS and LITHOGRAPHIC PRINTER, 25 Channel Street, Galashiels. ADVERTISEMENT. NEW MODEL OF THE People's Cottage Piano —^~~t» fj i «y <kj»~ — PATERSON & SONS would draw Special Attention to this New Model, which is undoubtedly the Cheapest and Best Cottage Piano ever offered, and not only A CHEAP PIANO, but a Thoroughly Reliable Instrument, with P. & Sons' Guakantee. On the Hire System at 21s per Month till paid up. Descriptive Price-Lists on Application, or sent Free by Post. A Large Selection of Slightly-used Instruments returned from Hire will be Sold at Great Reductions. Sole Agents for the Steinway and Bechstein Pianofortes, the two Greatest Makers of the present century. Catalogues on Application. PATEESON <Sc SONS, Musicsellers to the Queen, 27 George Street, EDINBURGH. PATERSON & SONS' Tuners visit the Principal Districts of Scotland Quarterly, and can give every information as to the Purchase or Exchanne of Pianofortes. Orders left with John McQueen, "Border Record" Office, Galashiels, shall receive prompt attention. A life V'C WELLINGTON KNIFE POLISH. 1 *™ KKL f W % Prepared for Oakey's Knife-Boards and all Patent Knife- UfgWa^^""Kmm ^"it— I U Clea-iing Machines. -

A Singular Solace: an Ecclesiastical History of Haddington, 1560-2000

A Singular Solace: An Ecclesiastical History of Haddington, 1560-2000 David William Dutton BA, MTh October 2020 This dissertation is submitted in part fulfilment of the requirements of the University of Stirling for the degree of Master of Philosophy in History. Division of History and Politics 1 Research Degree Thesis Submission Candidates should prepare their thesis in line with the code of practice. Candidates should complete and submit this form, along with a soft bound copy of their thesis for each examiner, to: Student Services Hub, 2A1 Cottrell Building, or to [email protected]. Candidate’s Full Name: DAVID WILLIAM DUTTON Student ID: 2644948 Thesis Word Count: 49,936 Maximum word limits include appendices but exclude footnotes and bibliographies. Please tick the appropriate box MPhil 50,000 words (approx. 150 pages) PhD 80,000 words (approx. 300 pages) PhD (by publication) 80,000 words (approx. 300 pages) PhD (by practice) 40,000 words (approx. 120 pages) Doctor of Applied Social Research 60,000 words (approx. 180 pages) Doctor of Business Administration 60,000 (approx. 180 pages) Doctor of Education 60,000 (approx. 180 pages) Doctor of Midwifery / Nursing / Professional Health Studies 60,000 (approx. 180 pages) Doctor of Diplomacy 60,000 (approx. 180 pages) Thesis Title: A Singular Solace: An Ecclesiastical History of Haddington, 1560-2000 Declaration I wish to submit the thesis detailed above in according with the University of Stirling research degree regulations. I declare that the thesis embodies the results of my own research and was composed by me. Where appropriate I have acknowledged the nature and extent of work carried out in collaboration with others included in the thesis. -

Welcome to Midlothian (PDF)

WELCOME TO MIDLOTHIAN A guide for new arrivals to Midlothian • Transport • Housing • Working • Education and Childcare • Staying safe • Adult learning • Leisure facilities • Visitor attractions in the Midlothian area Community Learning Midlothian and Development VISITOr attrACTIONS Midlothian Midlothian is a small local authority area adjoining Edinburgh’s southern boundary, and bordered by the Pentland Hills to the west and the Moorfoot Hills of the Scottish Borders to the south. Most of Midlothian’s population, of just over 80,000, lives in or around the main towns of Dalkeith, Penicuik, Bonnyrigg, Loanhead, Newtongrange and Gorebridge. The southern half of the authority is predominantly rural, with a small population spread between a number of villages and farm settlements. We are proud to welcome you to Scotland and the area www.visitmidlothian.org.uk/ of Midlothian This guide is a basic guide to services and • You are required by law to pick up litter information for new arrivals from overseas. and dog poo We hope it will enable you to become a part of • Smoking is banned in public places our community, where people feel safe to live, • People always queue to get on buses work and raise a family. and trains, and in the bank and post You will be able to find lots of useful information on office. where to stay, finding a job, taking up sport, visiting tourist attractions, as well as how to open a bank • Drivers thank each other for being account or find a child-minder for your children. considerate to each other by a quick hand wave • You can safely drink tap water There are useful emergency numbers and references to relevant websites, as well as explanations in relation to your rights to work. -

Settlement Profile Jedburgh

SETTLEMENT PROFILE JEDBURGH HOUSING MARKET AREA LOCALITY POPULATION Central Cheviot 4,030 PLACEMAKING CONSIDERATIONS The historic settlement of Jedburgh was built either side of the Jed Water which runs on a north-south axis, and is framed by Lanton Hill (280 metres) and Black Law (338 metres) to the west and south west and by lower more undulating hills to the east. The Conservation Area of Jedburgh includes much of the historic core of the town including the Abbey and the Castle Gaol. Similar to Edinburgh Old Town in its layout, Jedburgh has a long street that rises terminating with the castle at the highest point. The High Street is characterised by a mix of commercial, residential and social facilities, the central area is focused around where the Mercat Cross once sat with roads leading off in various directions. Properties within the Conservation Area are built in rows with some detached properties particularly along Friarsgate. Ranging from two to three and a half storeys in height, properties vary in styles. Although the elements highlighted above are important and contribute greatly to the character of Jedburgh they do not do so in isolation. Building materials and architectural details are also just as important. Sandstone, some whinstone, harling, and slate all help to form the character. Architectural details such as sash and case windows (though there are some unfortunate uPVC replacements), rybats, margins, detailed door heads above some entrances and in some instances pilasters all add to the sense of place. Any new development must therefore aim to contribute to the existing character of the Conservation Area. -

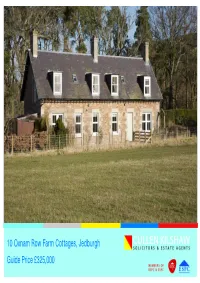

10 Oxnam Row.Pmd

10 Oxnam Row Farm Cottages, Jedburgh Guide Price £325,000 10 Oxnam Row is a well-presented detached cottage which LOCATION DIRECTIONS sits amidst stunning Scottish Borders countryside above Oxnam is an attractive small Borders village set amidst rolling From the A68 heading north take the right turn in Camptown, Oxnam Water and within easy reach of the historic market farmland yet just a short distance from Jedburgh. The mainly just before the bridge over Jed Water. Follow this road for 3.4 residential village offers an active community-owned village town of Jedburgh. The property was originally two miles and then turn right into the driveway and the entrance hall. A short drive away is the popular market town of Jedburgh gates for number 10 Oxnam Row will be straight ahead. cottages which have been combined to provide a bright where there is a good range of amenities including a wide and spacious home with high-quality fixtures and fittings range of shops, professional services, schools, health centre, supermarket, restaurants, cafes and a wide range of leisure including handmade solid oak doors. The front door opens amenities. Jedburgh is one of the most historic towns in the into an entrance hall which has a large storage cupboard Scottish Borders with many fine buildings including the Abbey. and stairs to the upper floor. The bright, dual aspect The main A68 is a short distance from the property which makes many of the surrounding Borders towns and villages within easy reception hall has two window seats offering stunning open commuting distance and providing access to Edinburgh and rural views; this room has flexible use as either a second Newcastle. -

Denholm Hall Farm East Draft Planning Brief

This page is intentionally blank. Denholm Hall Farm East Development Brief Contents Introduction 2 Local context 3 Policy context 4 Background 6 Site analysis 6 Opportunities & constraints 7 Development vision 9 Development contributions 11 Submission requirements 12 Contacts 14 Alternative format/language paragraph 16 Figure 1 Denholm Hall Farm East Site 2 Figure 2 Local context 3 Figure 3 Site analysis of key issues 5 Figure 4 Development vision 8 1 Denholm Hall Farm East Development Brief Introduction This brief sets out the main objectives and issues to be addressed in the development of two adjacent housing sites: - Denholm Hall Farm (RD4B); and - Denholm Hall Farm East (ADENH001) The sites are located on the north east edge of Denholm Village and the boundaries are shown on the aerial photograph in Figure 1. The brief provides a framework for the future development of the sites which are allocated for housing in the Consolidated Scottish Borders Local Plan 2011. The brief identifies where detailed attention to specific issues is required and where developer contributions will be sought. The brief should be read alongside relevant national, strategic and local planning guidance, a selection of which is provided on page 4, and should be a material consideration for any planning application submitted for the site. The development brief should be read in conjunction with the developer guidance in Annex A ???? Figure 1—Denholm Hall Farm East housing site - aerial view 2 Denholm Hall Farm East Development Brief Local context Figure 2—Local Context Denholm is situated in the central Borders, mid-way between Hawick and Jedburgh on the A698. -

Borders Family History Society Sales List February 2021

Borders Family History Society www.bordersfhs.org.uk Sales List February 2021 Berwickshire Roxburghshire Census Transcriptions 2 Census Transcriptions 8 Death Records 3 Death Records 9 Monumental Inscriptions 4 Monumental Inscriptions 10 Parish Records 5 Parish Records 11 Dumfriesshire Poor Law Records 11 Parish Records 5 Prison Records 11 Edinburghshire/Scottish Borders Selkirkshire Census Transcriptions 5 Census Transcriptions 12 Death Records 5 Death Records 12 Monumental Inscriptions 5 Monumental Inscriptions 13 Peeblesshire Parish Records 13 Census Transcriptions 6 Prison Records 13 Death Records 7 Other Publications 14 Monumental Inscriptions 7 Maps 17 Parish Records 7 Past Magazines 17 Prison Records 7 Postage Rates 18 Parish Map Diagrams 19 Borders FHS Monumental Inscriptions are recorded by a team of volunteer members of the Society and are compiled over several visits to ensure accuracy in the detail recorded. Additional information such as Militia Lists, Hearth Tax, transcriptions of Rolls of Honour and War Memorials are included. Wherever possible, other records are researched to provide insights into the lives of the families who lived in the Parish. Society members may receive a discount of £1.00 per BFHS monumental inscription volume. All publications can be ordered through: online : via the Contacts page on our website www.bordersfhs.org.uk/BFHSContacts.asp by selecting Contact type 'Order for Publications'. Sales Convenor, Borders Family History Society, 52 Overhaugh St, Galashiels, TD1 1DP, mail to : Scotland Postage, payment, and ordering information is available on page 17 NB Please note that many of the Census Transcriptions are on special offer and in many cases, we have only one copy of each for sale. -

Note on the Antiquity of the Wheel Causeway. by F

THE ANTIQUIT WHEEE TH F LYO CAUSEWAY9 12 . TV. NOTE ON THE ANTIQUITY OF THE WHEEL CAUSEWAY. BY F. HAVERFIELD, M.A., F.S.A. On 1895y 13t r JamehMa D , s Macdoimlcl rea thio t d s Societ papeya r e allegeoth n d Roman roa n Roxburghshirei d , commonly callee th d Wheel Causeway. He admitted that the Causeway was a real road of some sort, butreasonr fo , s which see mo t e satisfactory deniee h , d that it possessed any claim to be considered a Roman road. He did not, however, go on to discuss its history, and his silence produced a doubtless unintentional impression tha t i migha vert e yb t modern affair, first dignified by some over-enthusiastic antiquary with the title Causeway. I was rash enough, myself, to suggest as much in an article which I wrote two or three years ago on the Maiden Way (Transactions of the Cumberland Westmorlandd an Arch. Society, xiv. ' Wheelri432) A . g ' Whee Heada d l an Whee'Kirkd an close , ar 'l e by Causeway mighI ( t thought) have been named after them. This suggestion I find to be wrong : both road and name can lay claim to a respectable antiquity, and it may not be amiss to put together a few details about them. Thoug Middle t Roman useroae s th no h th n s wa di i e t i , Age pasa s sa fro headwatere mth Norte th f ho s Tyn Northumberlann ei heade th o -dt waters of the Jed and other tributaries of the Teviot. -

Jedburgh Tow Ur H Town T N Trail

je d b u r gh t ow n t ra il . jed bu rgh tow n tr ail . j edburgh town trail . jedburgh town trail . jedburgh town trail . town trail . jedb urgh tow n t rai l . je dbu rgh to wn tr ail . je db ur gh to wn tra il . jedb urgh town trail . jedburgh town jedburgh je db n trail . jedburgh town trail . jedburgh urg gh tow town tr h t jedbur ail . jed ow trail . introductionburgh n tr town town ail . burgh trail jedb il . jed This edition of the Jedburgh Town Trail has be found within this leaflet.. jed As some of the rgh urgh tra been revised by Scottish Borders Council sites along the Trail are houses,bu rwe ask you to u town tra rgh town gh tow . jedb il . jedbu working with the Jedburgh Alliance. The aim respect the owners’ privacy. n trail . je n trail is to provide the visitor to the Royal Burgh of dburgh tow Jedburgh with an added dimension to local We hope you will enjoy walking Ma rk et history and to give a flavour of the town’s around the Town Trail P la development. and trust that you ce have a pleasant 1 The Trail is approximately 2.5km (1 /2 miles) stay in Jedburgh long. This should take about two hours to complete but further time should be added if you visit the Abbey and the Castle Jail. Those with less time to spare may wish to reduce this by referring to the Trail map which is found in the centre pages. -

Excavations at Kelso Abbey Christophe Tabrahamrj * with Contribution Ceramie Th N So C Materia Eoiy B L N Cox, George Haggart Johd Yhursan N G T

Proc Antlqc So Scot, (1984), 365-404 Excavations at Kelso Abbey Christophe TabrahamrJ * With contribution ceramie th n so c materia Eoiy b l n Cox, George Haggart Johd yHursan n G t 'Here are to be seen the Ruines of an Ancient Monastery founde Kiny db g David' (John Slezer, Theatrum Scotlae) SUMMARY The following is a report on an archaeological investigation carried out in 1975 and 1976 on garden ground a little to the SE of the surviving architectural fragment of this Border abbey. Evidence was forthcoming of intensive occupation throughout the monastery's existence from the 16ththe 12th to centuries. area,The first utilized perhaps a masons' as lodge duringthe construction of the church and cloister, was subsequently cleared before the close of the 12th century to accommodate the infirmary hall and its associated buildings. This capacious structure, no doubt badly damaged during Warsthe Independence, of largelyhad beenof abandonedend the by the 15th century when remainingits walls were partially taken down anotherand dwelling erected upon the site. This too was destroyed in the following century, the whole area becoming a handy stone quarry for local inhabitants before reverting to open ground. INTRODUCTION sourca s i f regret o I e t that Kelso oldeste th , wealthiese th , mose th td powerfutan e th f o l four Border abbeys, should have been the one to have survived the least unimpaired. Nothing of e cloisteth r sav e outeth e r parlour remain t whas (illubu , t 4) survives e churcth s beef so hha n described 'of surpassing interest as one of the most spectacular achievements of Romanesque architecture in Scotland' (Cruden 1960, 60).