APPENDIX XXXI V. History of the Constitutional Convention of 1776.1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pa Archives Vol

..’ JOHN 13. I.INN% WM.H. EGLE. M.D PROCEEDINGS OP THE CONVENTION FOR THE &tOVINCE 01; h~SYI,VANIA, HELD AT PHILADELPHIA, FROMJANUARY ‘3, 1775,TO J.4NUARY 3s 177~;. PROCEEDINGS. At a Provincial Convention for the Province of Pennsylvania, held at Philadelphia, Jan. 23, 1775, and continued by adjourn- ments, from day to day, to the 28th. PRESI%:NT: For the City and Liberties of Philadelphia: John Dickinson, Esq., John Cox, Thomas Mifflin, Esq., John Bayard, Charles Thomson, Esq., Christopher Ludwig, John Cadwalader, Esq., Thomas Barclay, George Clymer, Esq., George Schlosser, Joseph Reed, Esq., Jonathan B. Smith, Samuel Meredith, Francis Wade, William Rush, Lambert Csdwalnder, James Mease, Rcynold Keen, John Nixon, Richard Bathe, John Benezet, Samuel Penrose, Jacob Rush, Isaac Coates, William Bradford, William Coates, Elias Boys, Blathwaite Jones, James Robinson, Thomas Pryor, Manuel Eyre, Samuel Massey, Owen Biddle, Robert Towers, William H.eysham, Henry Jones, James Milligan, Joseph Wetherill, John Wilcox, Joseph C’opperthwaite, Sharp Delany, Joseph Dean, Francis Gurney, Benjamin Harbeson, John Purviance, James Ash, Robert Knox, Benjamin Losley, Francis Hassenclever, William Robinson, Thomas Cuthbert, Sen., Ricloff Albcrson, William Jackson, James Irvine. Isaac Melcher, 626 PROCEEDINGS OF TIIE Philadelphia Cownty. George Gray, Esq., Benjamin Jacobs, John Bull, Esq., John Moore, Esq., Samuel Ashmead, Esq. Samuel Miles, Esq., Samuel Ervine, Esq., Edward Milnor, John Roberts, Jacob Lnughlau, Thomas Ashton, Melchior Waggoner. Chester Cozlnty . Anthony Wayne, Esq., Lewis Davis, Hugh Lloyd, William Montgomery, Richard Thomas, Joseph Musgrave, Francis Johnson, Esq., Joshua Evans, Samuel Fairlamb, Persiier Frazer. Lancaster County. Adam Simon Kuhn, Esq., Sebastian Graaff, James Clemson, Esq., David Jenkins, Peter Grubb, Eartram Galbraith. -

Northampton Township Summer 2017 Newsletter

TownshipTownship SUMMER 2017 BUCKS COUNTY, PENNSYLVANIA Northampton Township Welcomes Summer 2017 Inside This Issue Hello Everyone, Northampton Township hope your summer is off to a great start! This issue of the Township Newsletter is packed with information Contact Information ...................... 3 Iabout many of the projects the Board of Supervisors and Administration have been working on for many years. All this hard work is now starting to come to fruition. Many exciting projects are nearing completion and all Trash Information .............................. 3 Northampton Township residents will begin seeing the positive benefits of these projects. Administration .................................. 4 The Board recently approved amendments to our zoning and subdivision and land development ordinances that incorporate design guidelines for the Village Overlay Districts of Richboro and Holland. The objectives of Tax Collector ..................................... 4 these amendments are to define uniform design standards to further the vision for the Village Overlay Districts (details on page 7). Public Works ..................................... 5 Another exciting development is the rebirth of the Mill Race Inn. After being closed for nearly 20 years, there is Northampton Township a renaissance for the Inn in the near future. In April, the Board approved a proposal from a developer to restore Police Department ......................... 5 the original mill building and incorporate into a Mediterranean Restaurant and event space for 100 to 150 people. Thanks to the Bucks County Redevelopment Authority for their assistance in this project (details on page 6). Mill Race Inn Redevelopment ............ 6 Late last year, the Public Works Building Expansion Project got under way and is nearing completion in mid- Northampton Township July. This project will significantly increase the efficiencies of Department operation and provide much needed Office of the Fire Marshal ............. -

3\(Otes on the 'Pennsylvania Revolutionaries of 17J6

3\(otes on the 'Pennsylvania Revolutionaries of 17j6 n comparing the American Revolution to similar upheavals in other societies, few persons today would doubt that the Revolu- I tionary leaders of 1776 possessed remarkable intelligence, cour- age, and effectiveness. Today, as the bicentennial of American inde- pendence approaches, their work is a self-evident monument. But below the top leadership level, there has been little systematic col- lection of biographical information about these leaders. As a result, in the confused welter of interpretations that has developed about the Revolution in Pennsylvania, purportedly these leaders sprung from or were acting against certain ill-defined groups. These sup- posedly important political and economic groups included the "east- ern establishment/' the "Quaker oligarchy/' ''propertyless mechan- ics/' "debtor farmers/' "new men in politics/' and "greedy bankers." Regrettably, historians of this period have tended to employ their own definitions, or lack of definitions, to create social groups and use them in any way they desire.1 The popular view, originating with Charles Lincoln's writings early in this century, has been that "class war between rich and poor, common people and privileged few" existed in Revolutionary Pennsylvania. A similar neo-Marxist view was stated clearly by J. Paul Selsam in his study of the Pennsylvania Constitution of 1776:2 The struggle obviously was based on economic interests. It was a conflict between the merchants, bankers, and commercial groups of the East and the debtor agrarian population of the West; between the property holders and employers and the propertyless mechanics and artisans of Philadelphia. 1 For the purposes of brevity and readability, the footnotes in this paper have been grouped together and kept to a minimum. -

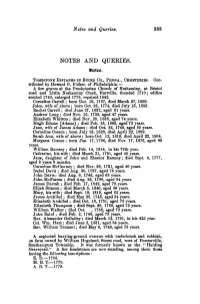

NOTES and QUEEIE8. •Rotes

Notes and Queries. 233 NOTES AND QUEEIE8. •Rotes. TOMBSTONE EPITAPHS IN BUCKS CO., PENNA., CEMETERIES. Con- tributed by Howard 0. Folker, of Philadelphia.— A few graves at the Presbyterian Church of Neshaminy, at Bristol road and Little Neshaminy Creek, Hartville, founded 1710; edifice erected 1743, enlarged 1775, repaired 1842. Cornelius Carrell; born Dec. 10, 1767, died March 27, 1850. Joice, wife of above; born Oct. 28, 1774, died July 15, 1856. Rachel Carrell; died June 27, 1832, aged 61 years. Andrew Long ; died Nov. 16, 1738, aged 47 years. Elizabeth Whitton ; died Nov. 23, 1838, aged 74 years. Hugh Edams [Adams] ; died Feb. 18, 1803, aged 72 years. Jane, wife of James Adams; died Oct. 22, 1746, aged 55 years. Cornelius Corson ; born July 13, 1823, died April 22, 1899. Sarah Ann, wife of above ; born Oct. 12, 1819, died April 22, 1904. Margaret Corson ; born Jan. 17, 1796, died Nov. 17, 1876, aged 80 years. William Ramsey ; died Feb. 14, 1814, in his 79th year. Catharine, his wife; died March 31, 1791, aged 45 years. Jane, daughter of John and Eleanor Ramsey; died Sept. 4, 1777, aged 3 years 9 months. Cornelius McCawney ; died Nov. 29, 1731, aged 40 years. Isabel Davis ; died Aug. 30, 1737, aged 78 years. John Davis; died Aug. 6, 1748, aged 63 years. John McFarren ; died Aug. 26, 1789, aged 84 years. James Darrah ; died Feb. 17, 1842, aged 78 years. Elijah Stinson ; died March 5, 1840, aged 89 years. Mary, his wife; died Sept" 19, 1819, aged 63 years. James Archibel; died May 25, 1748, aged 34 years. -

Martin's Bench and Bar of Philadelphia

MARTIN'S BENCH AND BAR OF PHILADELPHIA Together with other Lists of persons appointed to Administer the Laws in the City and County of Philadelphia, and the Province and Commonwealth of Pennsylvania BY , JOHN HILL MARTIN OF THE PHILADELPHIA BAR OF C PHILADELPHIA KKKS WELSH & CO., PUBLISHERS No. 19 South Ninth Street 1883 Entered according to the Act of Congress, On the 12th day of March, in the year 1883, BY JOHN HILL MARTIN, In the Office of the Librarian of Congress, at Washington, D. C. W. H. PILE, PRINTER, No. 422 Walnut Street, Philadelphia. Stack Annex 5 PREFACE. IT has been no part of my intention in compiling these lists entitled "The Bench and Bar of Philadelphia," to give a history of the organization of the Courts, but merely names of Judges, with dates of their commissions; Lawyers and dates of their ad- mission, and lists of other persons connected with the administra- tion of the Laws in this City and County, and in the Province and Commonwealth. Some necessary information and notes have been added to a few of the lists. And in addition it may not be out of place here to state that Courts of Justice, in what is now the Com- monwealth of Pennsylvania, were first established by the Swedes, in 1642, at New Gottenburg, nowTinicum, by Governor John Printz, who was instructed to decide all controversies according to the laws, customs and usages of Sweden. What Courts he established and what the modes of procedure therein, can only be conjectur- ed by what subsequently occurred, and by the record of Upland Court. -

H. Doc. 108-222

THE CONGRESS OF THE UNITED STATES 1789–2005 [ 43 ] TIME AND PLACE OF MEETING The Constitution (Art. I, sec. 4) provided that ‘‘The Congress shall assemble at least once in every year * * * on the first Monday in December, unless they shall by law appoint a different day.’’ Pursuant to a resolution of the Continental Congress the first session of the First Congress convened March 4, 1789. Up to and including May 20, 1820, eighteen acts were passed providing for the meet- ing of Congress on other days in the year. Since that year Congress met regularly on the first Mon- day in December until January 1934. The date for convening of Congress was changed by the Twen- tieth Amendment to the Constitution in 1933 to the 3d day of January unless a different day shall be appointed by law. The first and second sessions of the First Congress were held in New York City; subsequently, including the first session of the Sixth Congress, Philadelphia was the meeting place; since then Congress has convened in Washington, D.C. [ 44 ] FIRST CONGRESS MARCH 4, 1789, TO MARCH 3, 1791 FIRST SESSION—March 4, 1789, 1 to September 29, 1789 SECOND SESSION—January 4, 1790, to August 12, 1790 THIRD SESSION—December 6, 1790, to March 3, 1791 VICE PRESIDENT OF THE UNITED STATES—JOHN ADAMS, of Massachusetts PRESIDENT PRO TEMPORE OF THE SENATE—JOHN LANGDON, 2 of New Hampshire SECRETARY OF THE SENATE—SAMUEL A. OTIS, 3 of Massachusetts DOORKEEPER OF THE SENATE—JAMES MATHERS, 4 of New York SPEAKER OF THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES—FREDERICK A. -

A Genealogy of the Hiester Family

Gc 929.2 H532h 1339494 GENEALOGY COLLECTION 3 1833 03153 3554 A GENEALOGY The Hiester Family By V. E. a HILL PRINTED FOR PRIVATE DISTRIBUTION LEBANON. PA. REPORT PUBLISHING COMPANY 1903 1339494 1 "Knowledge of kindred and the genealogies of the ancient families v' dcscrvcth the highest praise. Herein consisteth a part of the knowledge of a man's own self. It is a great spur to virtue to look hack on the worth ^-} of our line."—Lord Bacon. Coat of Arms of the Hiester Family. [Copiei] from a record of the Hiester family by Mr. H. M. M. Richards, of Beading, THE origin of the Hiester Family was the Silesian knight, Premiscloros Hiisterniz, who flourished about 1329, and held the office of Mayor, or Town Captain of the city of Swineford. "A. D. 1480, the Patrician and Counsellor of Swineford, Adol- phus Louis, called 'der Hiester,' obtained from the Emperor Frederick, letters patent whereby he and his posterity were au- thorized to use the coat-of-arms he had inherited from his ances- tors, to whom it was formerly granted, with the faculty of trans- mitting the same as an hereditary right and privilege to all his descendants. "The Hiester family was afterward diffused through Austria, Saxony, Switzerland and other countries bordering on the river Rhine. Several of the members were distinguished statesmen and ministers of religion and among the Senators of Homburg, B-emen and Ratisbon, where many of the same name were found who afterward held the highest and most important offices in said cities. The first part of this sketch Is a translatiou from the German by G. -

Pennsylvania History (People, Places, Events) Record Holdings Scholars in Residence Pennsylvania History Day People Places Events Things

rruVik.. reliulsyiVUtlll L -tiestuly ratge I UI I Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission Home Programs & Events Researchr Historic Sites & Museums Records Management About Us Historic Preservation Pennsylvania State Archives CRGIS: Cultural Resources Geographic Information Doc Heritage Digital Archives (ARIAS) 0OF ExplorePAhistory.com V Land Records things Genealogy Pennsylvania History (People, Places, Events) Record Holdings Scholars in Residence Pennsylvania History Day People Places Events Things Documentary Heritaae Pennsylvania Governors Symbols and Official Designations Examples: " Keystone State," Flower, Tree Penn-sylyania Counties Outline of Pennsylvania History 1, n-n. II, ni, tv, c.tnto ~ no Ii~, ol-, /~~h nt/n. mr. on, ,t on~~con A~2 1 .rrniV1%', reiniSy1Vdaina riiSiur'y ragcaeiuo I ()I U Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission lome Programs & Events Research Historic Sites & Museums Records Management About Us Historic Preservation Pennsylvania State Archives PENNSYLVANIA STATE CRGIS: Cultural Resources Geographic Information HISTO RY Doc Heritage Digital Archives (ARIAS) ExplorePAhistory.com Land Records THE QUAKER PROVINCE: 1681-1776 Genealogy Pennsylvania History . (People, Places, Events) Record Holdings Y Scholars in Residence Pennsylvania History Day The Founding of Pennsylvania William Penn and the Quakers Penn was born in London on October 24, 1644, the son of Admiral Sir William Penn. Despite high social position and an excellent education, he shocked his upper-class associates by his conversion to the beliefs of the Society of Friends, or Quakers, then a persecuted sect. He used his inherited wealth and rank to benefit and protect his fellow believers. Despite the unpopularity of his religion, he was socially acceptable in the king's court because he was trusted by the Duke of York, later King James II. -

Lpennmglvaniaerman Genealogies

C KN LE D M E A OW G NT . Whil e under o bl ig a t io n s to various friends who have aided him in the compilation of this genealogy , the author desires to acknowledge especially the valuable assistance rendered him E . by Mrs . S . S . Hill (M iss Valeria Clymer) C O P YR IG HT E D 1 907 B Y T HE p ennspl vaniazmet m an S ociety . GENEALOGY O THE HIESTE R F MI F A LY. SCUTCHEON : A r is zu e , o r . a Sun , Crest : B e tween two horns , surm ount o ffr o n t é ing a helmet , a sun m as in the Ar s . Th e origin of the Hiester family was the Silesian Knight Pr em iscl o ro s Hii s t e rn iz flo , who urished about 1 3 2 9 and held the o fli ce o r T of Mayor, own Cap o f tain , the city of Swine ford . f . 1 o A D . 4 8 0 the Patrician and Counsellor Swineford , ( Adolphus Louis , called der Hiester , obtained from the E mperor Frederick letters patent , whereby he and his posterity were authorized t o use the coat- o f- arms he had inherited from his ancestors , to whom it was formerly o f granted , with the faculty transmitting the same , as an hereditary right and privilege , to all his descendants . - - - D r . o n Lawrence Hiester , b Frankfort the Main , Sep 1 1 6 8 . 1 8 1 tember 9 , 3 , d Helmstedt , April , 7 5 8 , Professor 1 2 0 of Surgery at Helmstedt from 7 , and the founder of 6 n n a n i e r m a n o e t Th e P e sylv a G S ci y . -

Charles Willson Peale at Belfield La Salle University Art Museum

La Salle University La Salle University Digital Commons Art Museum Exhibition Catalogues La Salle University Art Museum Fall 1987 Charles Willson Peale at Belfield La Salle University Art Museum Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.lasalle.edu/exhibition_catalogues Part of the Fine Arts Commons, and the History of Art, Architecture, and Archaeology Commons Recommended Citation La Salle University Art Museum, "Charles Willson Peale at Belfield" (1987). Art Museum Exhibition Catalogues. 63. http://digitalcommons.lasalle.edu/exhibition_catalogues/63 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the La Salle University Art Museum at La Salle University Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Art Museum Exhibition Catalogues by an authorized administrator of La Salle University Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Charles Willson Peale at Belfield r \ CHARLES WILLSON PEALE AT BELFIELD An Exhibition Checklist La Salle University Art Museum October 1 - December 1,1987 We are indebted to the following lenders: The American Philosophical Society Library Marge Layne Greenbaum Germantown Historical Society Historical Society of Pennsylvania Independence National Historical Park Philadelphia Museum of Art Three Private Collectors This exhibition has been funded by a grant from Manufacturers Hanover Financial Services. PORTRAITS The commentary for the portraits is taken from Charles Coleman Sellers, "Portraits and Miniatures by Charles Willson Peale," Transactions of The American Philosophical Society. Vol 42, Part I, 1952, and quoted with their land permission. Elizabeth Miller c. 1788 Oil on canvas. 36 x 27 ins. Lent by the Historical Society of Pennsylvania Elizabeth, a daughter of William Miller, who came from Scotland to Philadelphia in 1755, and Katherine Kennedy, was born in 1764. -

Washington City, 1800-1830 Cynthia Diane Earman Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses Graduate School Fall 11-12-1992 Boardinghouses, Parties and the Creation of a Political Society: Washington City, 1800-1830 Cynthia Diane Earman Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Earman, Cynthia Diane, "Boardinghouses, Parties and the Creation of a Political Society: Washington City, 1800-1830" (1992). LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses. 8222. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses/8222 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. BOARDINGHOUSES, PARTIES AND THE CREATION OF A POLITICAL SOCIETY: WASHINGTON CITY, 1800-1830 A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in The Department of History by Cynthia Diane Earman A.B., Goucher College, 1989 December 1992 MANUSCRIPT THESES Unpublished theses submitted for the Master's and Doctor's Degrees and deposited in the Louisiana State University Libraries are available for inspection. Use of any thesis is limited by the rights of the author. Bibliographical references may be noted, but passages may not be copied unless the author has given permission. Credit must be given in subsequent written or published work. A library which borrows this thesis for use by its clientele is expected to make sure that the borrower is aware of the above restrictions. -

![[Pennsylvania County Histories]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/2093/pennsylvania-county-histories-3172093.webp)

[Pennsylvania County Histories]

?7 H-,r e 3 ji. ii V. 3 H Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2018 with funding from This project is made possible by a grant from the Institute of Museum and Library Services as administered by the Pennsylvania Department of Education through the Office of Commonwealth Libraries https://archive.org/details/pennsylvaniacoun34unse A •- INDEX. S Page S Page S * Paj -“- - - -m~ .. - *■- T U V w / W X YZ w -^ f love and sympathy for all. 1 low tru remark, “Bro. Graves is a good man. 5 i He has had a successful year at Strasburg and returns for the third time. (interesting letter from rev. ill In various parts of the church sat JAMES K. RAYMOND- id several others. S. T. Kemble reported a P successfull year at Bristol. J. S. Lame pi Ministers Wlio Have Served Middle- . is not far from Middletown—Cornwall, town 31et.!jodist lEpiwcwpal Church. ISome Middletowucrs still remember some !C^ When you consider that all the min¬ 'of his sermons on Heaven. He is a gen¬ isters of the M. E. church sent to Middle- ial and popular man—when sent to Corn¬ i town since it has been organized into a wall, a year ago, he had to resign the separate charge, in ISoG or 57, are living Presidency of the Philadelphia Preachers? to-day, with but one exception, (Rev. Meeting. L. B. Hughes comes up from Allen John, who was aged, and died of a hard field of labor with an encouraging >i general debility while stationed there), report, including $200 more salary than ^ ! it would seem that it is not such an un¬ that estimated at the beginning of the healthy appointment after all.