Suny, Brockport Partisanship and the Constitution

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

NOTES and QUEEIE8. •Rotes

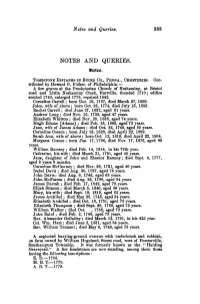

Notes and Queries. 233 NOTES AND QUEEIE8. •Rotes. TOMBSTONE EPITAPHS IN BUCKS CO., PENNA., CEMETERIES. Con- tributed by Howard 0. Folker, of Philadelphia.— A few graves at the Presbyterian Church of Neshaminy, at Bristol road and Little Neshaminy Creek, Hartville, founded 1710; edifice erected 1743, enlarged 1775, repaired 1842. Cornelius Carrell; born Dec. 10, 1767, died March 27, 1850. Joice, wife of above; born Oct. 28, 1774, died July 15, 1856. Rachel Carrell; died June 27, 1832, aged 61 years. Andrew Long ; died Nov. 16, 1738, aged 47 years. Elizabeth Whitton ; died Nov. 23, 1838, aged 74 years. Hugh Edams [Adams] ; died Feb. 18, 1803, aged 72 years. Jane, wife of James Adams; died Oct. 22, 1746, aged 55 years. Cornelius Corson ; born July 13, 1823, died April 22, 1899. Sarah Ann, wife of above ; born Oct. 12, 1819, died April 22, 1904. Margaret Corson ; born Jan. 17, 1796, died Nov. 17, 1876, aged 80 years. William Ramsey ; died Feb. 14, 1814, in his 79th year. Catharine, his wife; died March 31, 1791, aged 45 years. Jane, daughter of John and Eleanor Ramsey; died Sept. 4, 1777, aged 3 years 9 months. Cornelius McCawney ; died Nov. 29, 1731, aged 40 years. Isabel Davis ; died Aug. 30, 1737, aged 78 years. John Davis; died Aug. 6, 1748, aged 63 years. John McFarren ; died Aug. 26, 1789, aged 84 years. James Darrah ; died Feb. 17, 1842, aged 78 years. Elijah Stinson ; died March 5, 1840, aged 89 years. Mary, his wife; died Sept" 19, 1819, aged 63 years. James Archibel; died May 25, 1748, aged 34 years. -

A Genealogy of the Hiester Family

Gc 929.2 H532h 1339494 GENEALOGY COLLECTION 3 1833 03153 3554 A GENEALOGY The Hiester Family By V. E. a HILL PRINTED FOR PRIVATE DISTRIBUTION LEBANON. PA. REPORT PUBLISHING COMPANY 1903 1339494 1 "Knowledge of kindred and the genealogies of the ancient families v' dcscrvcth the highest praise. Herein consisteth a part of the knowledge of a man's own self. It is a great spur to virtue to look hack on the worth ^-} of our line."—Lord Bacon. Coat of Arms of the Hiester Family. [Copiei] from a record of the Hiester family by Mr. H. M. M. Richards, of Beading, THE origin of the Hiester Family was the Silesian knight, Premiscloros Hiisterniz, who flourished about 1329, and held the office of Mayor, or Town Captain of the city of Swineford. "A. D. 1480, the Patrician and Counsellor of Swineford, Adol- phus Louis, called 'der Hiester,' obtained from the Emperor Frederick, letters patent whereby he and his posterity were au- thorized to use the coat-of-arms he had inherited from his ances- tors, to whom it was formerly granted, with the faculty of trans- mitting the same as an hereditary right and privilege to all his descendants. "The Hiester family was afterward diffused through Austria, Saxony, Switzerland and other countries bordering on the river Rhine. Several of the members were distinguished statesmen and ministers of religion and among the Senators of Homburg, B-emen and Ratisbon, where many of the same name were found who afterward held the highest and most important offices in said cities. The first part of this sketch Is a translatiou from the German by G. -

Pennsylvania History (People, Places, Events) Record Holdings Scholars in Residence Pennsylvania History Day People Places Events Things

rruVik.. reliulsyiVUtlll L -tiestuly ratge I UI I Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission Home Programs & Events Researchr Historic Sites & Museums Records Management About Us Historic Preservation Pennsylvania State Archives CRGIS: Cultural Resources Geographic Information Doc Heritage Digital Archives (ARIAS) 0OF ExplorePAhistory.com V Land Records things Genealogy Pennsylvania History (People, Places, Events) Record Holdings Scholars in Residence Pennsylvania History Day People Places Events Things Documentary Heritaae Pennsylvania Governors Symbols and Official Designations Examples: " Keystone State," Flower, Tree Penn-sylyania Counties Outline of Pennsylvania History 1, n-n. II, ni, tv, c.tnto ~ no Ii~, ol-, /~~h nt/n. mr. on, ,t on~~con A~2 1 .rrniV1%', reiniSy1Vdaina riiSiur'y ragcaeiuo I ()I U Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission lome Programs & Events Research Historic Sites & Museums Records Management About Us Historic Preservation Pennsylvania State Archives PENNSYLVANIA STATE CRGIS: Cultural Resources Geographic Information HISTO RY Doc Heritage Digital Archives (ARIAS) ExplorePAhistory.com Land Records THE QUAKER PROVINCE: 1681-1776 Genealogy Pennsylvania History . (People, Places, Events) Record Holdings Y Scholars in Residence Pennsylvania History Day The Founding of Pennsylvania William Penn and the Quakers Penn was born in London on October 24, 1644, the son of Admiral Sir William Penn. Despite high social position and an excellent education, he shocked his upper-class associates by his conversion to the beliefs of the Society of Friends, or Quakers, then a persecuted sect. He used his inherited wealth and rank to benefit and protect his fellow believers. Despite the unpopularity of his religion, he was socially acceptable in the king's court because he was trusted by the Duke of York, later King James II. -

Lpennmglvaniaerman Genealogies

C KN LE D M E A OW G NT . Whil e under o bl ig a t io n s to various friends who have aided him in the compilation of this genealogy , the author desires to acknowledge especially the valuable assistance rendered him E . by Mrs . S . S . Hill (M iss Valeria Clymer) C O P YR IG HT E D 1 907 B Y T HE p ennspl vaniazmet m an S ociety . GENEALOGY O THE HIESTE R F MI F A LY. SCUTCHEON : A r is zu e , o r . a Sun , Crest : B e tween two horns , surm ount o ffr o n t é ing a helmet , a sun m as in the Ar s . Th e origin of the Hiester family was the Silesian Knight Pr em iscl o ro s Hii s t e rn iz flo , who urished about 1 3 2 9 and held the o fli ce o r T of Mayor, own Cap o f tain , the city of Swine ford . f . 1 o A D . 4 8 0 the Patrician and Counsellor Swineford , ( Adolphus Louis , called der Hiester , obtained from the E mperor Frederick letters patent , whereby he and his posterity were authorized t o use the coat- o f- arms he had inherited from his ancestors , to whom it was formerly o f granted , with the faculty transmitting the same , as an hereditary right and privilege , to all his descendants . - - - D r . o n Lawrence Hiester , b Frankfort the Main , Sep 1 1 6 8 . 1 8 1 tember 9 , 3 , d Helmstedt , April , 7 5 8 , Professor 1 2 0 of Surgery at Helmstedt from 7 , and the founder of 6 n n a n i e r m a n o e t Th e P e sylv a G S ci y . -

Charles Willson Peale at Belfield La Salle University Art Museum

La Salle University La Salle University Digital Commons Art Museum Exhibition Catalogues La Salle University Art Museum Fall 1987 Charles Willson Peale at Belfield La Salle University Art Museum Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.lasalle.edu/exhibition_catalogues Part of the Fine Arts Commons, and the History of Art, Architecture, and Archaeology Commons Recommended Citation La Salle University Art Museum, "Charles Willson Peale at Belfield" (1987). Art Museum Exhibition Catalogues. 63. http://digitalcommons.lasalle.edu/exhibition_catalogues/63 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the La Salle University Art Museum at La Salle University Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Art Museum Exhibition Catalogues by an authorized administrator of La Salle University Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Charles Willson Peale at Belfield r \ CHARLES WILLSON PEALE AT BELFIELD An Exhibition Checklist La Salle University Art Museum October 1 - December 1,1987 We are indebted to the following lenders: The American Philosophical Society Library Marge Layne Greenbaum Germantown Historical Society Historical Society of Pennsylvania Independence National Historical Park Philadelphia Museum of Art Three Private Collectors This exhibition has been funded by a grant from Manufacturers Hanover Financial Services. PORTRAITS The commentary for the portraits is taken from Charles Coleman Sellers, "Portraits and Miniatures by Charles Willson Peale," Transactions of The American Philosophical Society. Vol 42, Part I, 1952, and quoted with their land permission. Elizabeth Miller c. 1788 Oil on canvas. 36 x 27 ins. Lent by the Historical Society of Pennsylvania Elizabeth, a daughter of William Miller, who came from Scotland to Philadelphia in 1755, and Katherine Kennedy, was born in 1764. -

Washington City, 1800-1830 Cynthia Diane Earman Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses Graduate School Fall 11-12-1992 Boardinghouses, Parties and the Creation of a Political Society: Washington City, 1800-1830 Cynthia Diane Earman Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Earman, Cynthia Diane, "Boardinghouses, Parties and the Creation of a Political Society: Washington City, 1800-1830" (1992). LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses. 8222. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses/8222 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. BOARDINGHOUSES, PARTIES AND THE CREATION OF A POLITICAL SOCIETY: WASHINGTON CITY, 1800-1830 A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in The Department of History by Cynthia Diane Earman A.B., Goucher College, 1989 December 1992 MANUSCRIPT THESES Unpublished theses submitted for the Master's and Doctor's Degrees and deposited in the Louisiana State University Libraries are available for inspection. Use of any thesis is limited by the rights of the author. Bibliographical references may be noted, but passages may not be copied unless the author has given permission. Credit must be given in subsequent written or published work. A library which borrows this thesis for use by its clientele is expected to make sure that the borrower is aware of the above restrictions. -

![[Pennsylvania County Histories]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/2093/pennsylvania-county-histories-3172093.webp)

[Pennsylvania County Histories]

?7 H-,r e 3 ji. ii V. 3 H Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2018 with funding from This project is made possible by a grant from the Institute of Museum and Library Services as administered by the Pennsylvania Department of Education through the Office of Commonwealth Libraries https://archive.org/details/pennsylvaniacoun34unse A •- INDEX. S Page S Page S * Paj -“- - - -m~ .. - *■- T U V w / W X YZ w -^ f love and sympathy for all. 1 low tru remark, “Bro. Graves is a good man. 5 i He has had a successful year at Strasburg and returns for the third time. (interesting letter from rev. ill In various parts of the church sat JAMES K. RAYMOND- id several others. S. T. Kemble reported a P successfull year at Bristol. J. S. Lame pi Ministers Wlio Have Served Middle- . is not far from Middletown—Cornwall, town 31et.!jodist lEpiwcwpal Church. ISome Middletowucrs still remember some !C^ When you consider that all the min¬ 'of his sermons on Heaven. He is a gen¬ isters of the M. E. church sent to Middle- ial and popular man—when sent to Corn¬ i town since it has been organized into a wall, a year ago, he had to resign the separate charge, in ISoG or 57, are living Presidency of the Philadelphia Preachers? to-day, with but one exception, (Rev. Meeting. L. B. Hughes comes up from Allen John, who was aged, and died of a hard field of labor with an encouraging >i general debility while stationed there), report, including $200 more salary than ^ ! it would seem that it is not such an un¬ that estimated at the beginning of the healthy appointment after all. -

H. Doc. 108-222

FIFTH CONGRESS MARCH 4, 1797, TO MARCH 3, 1799 FIRST SESSION—May 15, 1797, to July 10, 1797 SECOND SESSION—November 13, 1797, to July 16, 1798 THIRD SESSION—December 3, 1798, to March 3, 1799 SPECIAL SESSIONS OF THE SENATE—March 4, 1797, for one day only; July 17, 1798 to July 19, 1798 VICE PRESIDENT OF THE UNITED STATES—THOMAS JEFFERSON, of Virginia PRESIDENT PRO TEMPORE OF THE SENATE—WILLIAM BRADFORD, 1 of Rhode Island; JACOB READ, 2 of South Carolina; THEODORE SEDGWICK, 3 of Massachusetts; JOHN LAURANCE, 4 of New York; JAMES ROSS, 5 of Pennsylvania SECRETARY OF THE SENATE—SAMUEL A. OTIS, of Massachusetts DOORKEEPER OF THE SENATE—JAMES MATHERS, of New York SPEAKER OF THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES—JONATHAN DAYTON, 6 of New Jersey CLERK OF THE HOUSE—JOHN BECKLEY, of Virginia; JONATHAN W. CONDY, 7 of Pennsylvania SERGEANT AT ARMS OF THE HOUSE—JOSEPH WHEATON, of Rhode Island DOORKEEPER OF THE HOUSE—THOMAS CLAXTON CONNECTICUT Henry Latimer MARYLAND SENATORS REPRESENTATIVE AT LARGE SENATORS 16 James Hillhouse James A. Bayard John Henry James Lloyd 17 Uriah Tracy GEORGIA John E. Howard REPRESENTATIVES AT LARGE REPRESENTATIVES John Allen SENATORS George Baer, Jr. Joshua Coit 8 James Gunn William Craik Jonathan Brace 9 Josiah Tattnall John Dennis George Dent Samuel W. Dana REPRESENTATIVES AT LARGE Nathaniel Smith William Hindman Abraham Baldwin James Davenport 10 William Matthews John Milledge William Edmond 11 Samuel Smith Chauncey Goodrich Richard Sprigg, Jr. 12 KENTUCKY Roger Griswold MASSACHUSETTS SENATORS SENATORS John Brown DELAWARE Benjamin Goodhue Humphrey Marshall SENATORS Theodore Sedgwick John Vining 13 REPRESENTATIVES REPRESENTATIVES Joshua Clayton 14 Thomas T. -

Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission Guide to Civil War Holdings

PENNSYLVANIA HISTORICAL AND MUSEUM COMMISSION GUIDE TO CIVIL WAR HOLDINGS 2009 Edition—Information current to January 2009 Dr. James P. Weeks and Linda A. Ries Compilers This survey is word-searchable in Adobe Acrobat. 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS Acknowledgements……………………………………………………………..page 3 Introduction by Dr. James P. Weeks………………………………….………...page 4 How to Use this Guide….………………………………………………………page 6 Abbreviations………….……………………..………………………….………page 7 Bureau of Archives and History State Archives Division, Record Groups………………………………..……....page 8 State Archives Division, Manuscript Groups…………………………………...page 46 State Archives Division, Affiliated Archives (Hartranft) ………………………page 118 PHMC Library …………………….……………………………………………page 119 Bureau of The State Museum of Pennsylvania Community and Domestic Life Section……………….………………………..page 120 Fine Arts Section……………………………………….…….…………...…… page 120 Military History Section……………………………….……..…………………page 126 Bureau of Historic Sites and Museums Pennsylvania Anthracite Heritage Museum………………………….……..…..page 131 Drake Well Museum Eckley Miner’s Village Erie Maritime Museum Landis Valley Museum Old Economy Village Pennsylvania Military Museum Railroad Museum of Pennsylvania Bureau for Historic Preservation State Historical Markers Program………………………………………………page 137 National Register of Historic Places and Register of Historical Landmarks……………………………….………………. ………………….…page 137 3 Acknowledgements This survey is a result of the PHMC Scholar-in-Residence (SIR) Program. In 2001, Diane Reed, Chief of the Commission’s Publications and Sales Division proposed that a book be created telling the story of Pennsylvania during the Civil War using the vast holdings of the PHMC. In order to create the book, an overview of the PHMC Civil War holdings was necessary. A SIR collaborative project was funded early in 2002, and Dr. James P. Weeks of the Pennsylvania State University History Department was chosen to create the survey, working with Linda Ries of the Archives staff. -

CONTINUE 1 Forms of Payment: Cash Check: CPC Visa Master Card Discover

Print Catalog Order Form Name:_______________________________________________________________________ Company Name: _____________________________________________________________ Address: _____________________________________________________________________ City: _______________________________ State: ____________ Zip:__________________ Phone: _____________________________ Email:__________________________________ Size *Luster Photo Paper Prints *Canvas Gloss Prints & Stretcher Frame Shipping 8X10 $23.95 $74.95 $6.95 11X14 $40.95 $86.95 $6.95 11X17 $47.95 $103.95 $6.95 16X20 $58.95 $109.95 $6.95 20X24 $69.95 $125.95 $6.95 24X30 $81.95 $174.95 $6.95 30X40 $96.95 $232.95 $9.95 *Luster E-Surface Paper (KODAK PROFESSIONAL Portra Endura Paper): Accurate color, realistic saturation, excellent neutral flesh reproduction and brighter colors are just a few of the attributes to describe E-Surface paper. Its 10-mil RC base gives prints a durable photographic feel, and has the highest color gamut available for vivid color reproduction. With this paper don’t worry about prints fading. The standard is 100 years in home display and 200 years in dark storage. *Artist Canvas – Gloss Finish: Poly/Cotton blend. Ideal for photographic & fine art reproductions. Gloss finish for optimum vibrancy, archival quality, and image stability. The canvas print(s) will be mounted on a custom stretcher frame so it will be ready for framing. # Title Format Size Price Qty. Luster Canvas Luster Canvas Luster Canvas Sub-Total $__________________________ S/H Fee (Mail Order Only) $__________________________ Sub-Total $__________________________ 6% PA Sales Tax $__________________________ Grand Total $__________________________ CONTINUE 1 Forms of Payment: Cash Check: CPC Visa Master Card Discover Name on Credit Card:_________________________________________________________ Billing Address: _______________________________________________________________ Credit Card #: ___ ___ ___ ___- ___ ___ ___ __- ___ ___ ___ ___-___ ___ ___ ___ Expiration Date: ___ ___/___ ___ CVV2# (Last 3 Digits above Sig. -

Library of Congress Classification

E AMERICA E America General E11-E29 are reserved for works that are actually comprehensive in scope. A book on travel would only occasionally be classified here; the numbers for the United States, Spanish America, etc., would usually accommodate all works, the choice being determined by the main country or region covered 11 Periodicals. Societies. Collections (serial) For international American Conferences see F1404+ Collections (nonserial). Collected works 12 Several authors 13 Individual authors 14 Dictionaries. Gazetteers. Geographic names General works see E18 History 16 Historiography 16.5 Study and teaching Biography 17 Collective Individual, see country, period, etc. 18 General works Including comprehensive works on America 18.5 Chronology, chronological tables, etc. 18.7 Juvenile works 18.75 General special By period Pre-Columbian period see E51+; E103+ 18.82 1492-1810 Cf. E101+ Discovery and exploration of America Cf. E141+ Earliest accounts of America to 1810 18.83 1810-1900 18.85 1901- 19 Pamphlets, addresses, essays, etc. Including radio programs, pageants, etc. 20 Social life and customs. Civilization. Intellectual life 21 Historic monuments (General) 21.5 Antiquities (Non-Indian) 21.7 Historical geography Description and travel. Views Cf. F851 Pacific coast Cf. G419+ Travels around the world and in several parts of the world including America and other countries Cf. G575+ Polar discoveries Earliest to 1606 see E141+ 1607-1810 see E143 27 1811-1950 27.2 1951-1980 27.5 1981- Elements in the population 29.A1 General works 29.A2-Z Individual elements, A-Z 29.A43 Akan 29.A73 Arabs 29.A75 Asians 29.B35 Basques Blacks see E29.N3 29.B75 British 29.C35 Canary Islanders 1 E AMERICA E General Elements in the population Individual elements, A-Z -- Continued 29.C37 Catalans 29.C5 Chinese 29.C73 Creoles 29.C75 Croats 29.C94 Czechs 29.D25 Danube Swabians 29.E37 East Indians 29.E87 Europeans 29.F8 French 29.G26 Galicians (Spain) 29.G3 Germans 29.H9 Huguenots 29.I74 Irish 29.I8 Italians 29.J3 Japanese 29.J5 Jews 29.K67 Koreans 29.N3 Negroes. -

APPENDIX XXXI V. History of the Constitutional Convention of 1776.1

APPENDIX XXXI V. SECTION I. History of the Constitutional Convention of 1776.1 SECTION II. Proceedings of the Provincial Conference held at Carpenter’s Hall from June 18, 1776, to June 26, 1776. SECTION III. Proceedings of the First Constitutional Convention of Penn sylvania, held at the State House, in Philadelphia, July 14, 1776, to September 28, 1776. SECTION IV. The First Constitution of Pennsylvania. SECTION I. HISTORY OF THE CONSTITUTIONAL CONVENTION OF 1776. The Constitutional Convention of 1776 was the outgrowth of the dissension between the conservative and reactionary parties in Pennsylvania politics, which had existed in various forms for many years, andwas brought to a climax by the move- ment for national independence. This account of the Constitutional Convention of 1776 is an abridgement (by Artemus Stewart, Esq.), of an article by the late Paul Leicester Ford, entitled “The Adoption of the Pennsylvania Constitution of 1776,” publIshed in the Political Science Quarterly, Vol. 10, ~. 426-459. This article, so far as the editor has been able to discover, is the only modern publication dealing critically with the subject; and in several instances, where Mr. Ford’s language did not admit of abridgement to any considerable degree, the article is here repro- duced verbatim. ~ (451) 452 The St&ules az~Large of Pennsylvania. [1776 Under the association which was formed in opposition to the revenue laws of 1767, and which lasted for upwards of two years, committees were established not only in the capitals of every province, but also in most of the country towns and subordinate districts. These committees were not only k~pt up after that association was at an end, but were greatly re- vised, extended and reduced to system, so that when any in- telligence of importance, of which it was deemed necessary to inform the people at large, reached the capital, it was at once sent to the county committees and by them forwarded to the committees of the districts, who disseminated it among the people.