A Canadian Political Thinker: Pierre Elliot Trudeau

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Victor‐Lévy Beaulieu and Québec's Linguistic and Cultural Identity Struggle

PSU McNair Scholars Online Journal Volume 3 Issue 1 Identity, Communities, and Technology: Article 14 On the Cusp of Change 2009 Victor‐Lévy Beaulieu and Québec's Linguistic and Cultural Identity Struggle Anna Marie Brown Portland State University Follow this and additional works at: https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/mcnair Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Brown, Anna Marie (2009) "Victor‐Lévy Beaulieu and Québec's Linguistic and Cultural Identity Struggle," PSU McNair Scholars Online Journal: Vol. 3: Iss. 1, Article 14. https://doi.org/10.15760/mcnair.2009.25 This open access Article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial- ShareAlike 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0). All documents in PDXScholar should meet accessibility standards. If we can make this document more accessible to you, contact our team. Portland State University McNair Research Journal 2009 Victor‐Lévy Beaulieu and Québec's Linguistic and Cultural Identity Struggle by Anna Marie Brown Faculty Mentor: Jennifer Perlmutter Citation: Brown, Anna Marie. Victor‐Lévy Beaulieu and Québec's Linguistic and Cultural Identity Struggle. Portland State University McNair Scholars Online Journal, Vol. 3, 2009: pages [25‐55] McNair Online Journal Page 1 of 31 Victor-Lévy Beaulieu and Québec's Linguistic and Cultural Identity Struggle Anna Marie Brown Jennifer Perlmutter, Faculty Mentor Six months ago, the latest literary work from Québécois author Victor-Lévy Beaulieu came off the presses. Known by his fans as simply VLB, Beaulieu is considered to be among the greatest contemporary Québec writers,1 and this most recent work, La Grande tribu, marks his seventieth. -

What Has He Really Done Wrong?

The Chrétien legacy Canada was in such a state that it WHAT HAS HE REALLY elected Brian Mulroney. By this stan- dard, William Lyon Mackenzie King DONE WRONG? easily turned out to be our best prime minister. In 1921, he inherited a Desmond Morton deeply divided country, a treasury near ruin because of over-expansion of rail- ways, and an economy gripped by a brutal depression. By 1948, Canada had emerged unscathed, enriched and almost undivided from the war into spent last summer’s dismal August Canadian Pension Commission. In a the durable prosperity that bred our revising a book called A Short few days of nimble invention, Bennett Baby Boom generation. Who cared if I History of Canada and staring rescued veterans’ benefits from 15 King had halitosis and a professorial across Lake Memphrémagog at the years of political logrolling and talent for boring audiences? astonishing architecture of the Abbaye launched a half century of relatively St-Benoît. Brief as it is, the Short History just and generous dealing. Did anyone ll of which is a lengthy prelude to tries to cover the whole 12,000 years of notice? Do similar achievements lie to A passing premature and imperfect Canadian history but, since most buy- the credit of Jean Chrétien or, for that judgement on Jean Chrétien. Using ers prefer their own life’s history to a matter, Brian Mulroney or Pierre Elliott the same criteria that put King first more extensive past, Jean Chrétien’s Trudeau? Dependent on the media, and Trudeau deep in the pack, where last seven years will get about as much the Opposition and government prop- does Chrétien stand? In 1993, most space as the First Nations’ first dozen aganda, what do I know? Do I refuse to Canadians were still caught in the millennia. -

The Judicial Function Under the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms Anne F Bayefsky

The Judicial Function under the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms Anne F Bayefsky* The author surveys the various American L'auteur resume les differentes theories am6- theories of judicial review in an attempt to ricaines du contr61e judiciaire dans le but de suggest approaches to a Canadian theory of sugg6rer une th6orie canadienne du r8le des the role of the judiciary under the Canadian juges sous Ia Charte canadiennedes droits et Charter of Rights and Freedoms. A detailed libert~s. Notamment, une 6tude d6taille de examination of the legislative histories of sec- 'histoire 1fgislative des articles 1, 52 et 33 de ]a Charte d6montre que les r~dacteurs ont tions 1, 52 and 33 of the Charterreveals that voulu aller au-delA de la Dclarationcana- the drafters intended to move beyond the Ca- dienne des droits et 6liminer le principe de ]a nadianBill ofRights and away from the prin- souverainet6 parlementaire. Cette intention ciple of parliamentary sovereignty. This ne se trouvant pas incorpor6e dans toute sa intention was not fully incorporated into the force au texte de Ia Charte,la protection des Charter,with the result that, properly speak- droits et libert~s au Canada n'est pas, Apro- ing, Canada's constitutional bill of rights is prement parler, o enchfiss~e )) dans ]a cons- not "entrenched". The author concludes by titution. En conclusion, l'auteur met 'accent emphasizing the establishment of a "contin- sur l'instauration d'un < colloque continu uing colloquy" involving the courts, the po- auxquels participeraient les tribunaux, les litical institutions, the legal profession and institutions politiques, ]a profession juri- society at large, in the hope that the legiti- dique et le grand public; ]a l6gitimit6 de la macy of the judicial protection of Charter protection judiciaire des droits garantis par rights will turn on the consent of the gov- la Charte serait alors fond6e sur la volont6 erned and the perceived justice of the courts' des constituants et Ia perception populaire de decisions. -

The Canadian Legal Research and Writing Guide Formerly the Best Guide to Canadian Legal Research 2018 Canliidocs 161

The Canadian Legal Research and Writing Guide Formerly the Best Guide to Canadian Legal Research 2018 CanLIIDocs 161 Edited by Melanie Bueckert, André Clair, Maryvon Côté, Yasmin Khan, and Mandy Ostick, based on work by Catherine Best, 2018 The Canadian Legal Research and Writing Guide is based on The Best Guide to Canadian Legal Research, An online legal research guide written and published by Catherine Best, which she started in 1998. The site grew out of Catherine’s experience teaching legal research and writing, and her conviction that a process-based analytical 2018 CanLIIDocs 161 approach was needed. She was also motivated to help researchers learn to effectively use electronic research tools. Catherine Best retired In 2015, and she generously donated the site to CanLII to use as our legal research site going forward. As Best explained: The world of legal research is dramatically different than it was in 1998. However, the site’s emphasis on research process and effective electronic research continues to fill a need. It will be fascinating to see what changes the next 15 years will bring. The text has been updated and expanded for this publication by a national editorial board of legal researchers: Melanie Bueckert legal research counsel with the Manitoba Court of Appeal in Winnipeg. She is the co-founder of the Manitoba Bar Association’s Legal Research Section, has written several legal textbooks, and is also a contributor to Slaw.ca. André Clair was a legal research officer with the Court of Appeal of Newfoundland and Labrador between 2010 and 2013. He is now head of the Legal Services Division of the Supreme Court of Newfoundland and Labrador. -

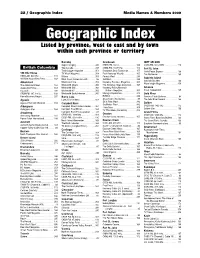

Geographic Index Media Names & Numbers 2009 Geographic Index Listed by Province, West to East and by Town Within Each Province Or Territory

22 / Geographic Index Media Names & Numbers 2009 Geographic Index Listed by province, west to east and by town within each province or territory Burnaby Cranbrook fORT nELSON Super Camping . 345 CHDR-FM, 102.9 . 109 CKRX-FM, 102.3 MHz. 113 British Columbia Tow Canada. 349 CHBZ-FM, 104.7mHz. 112 Fort St. John Truck Logger magazine . 351 Cranbrook Daily Townsman. 155 North Peace Express . 168 100 Mile House TV Week Magazine . 354 East Kootenay Weekly . 165 The Northerner . 169 CKBX-AM, 840 kHz . 111 Waters . 358 Forests West. 289 Gabriola Island 100 Mile House Free Press . 169 West Coast Cablevision Ltd.. 86 GolfWest . 293 Gabriola Sounder . 166 WestCoast Line . 359 Kootenay Business Magazine . 305 Abbotsford WaveLength Magazine . 359 The Abbotsford News. 164 Westworld Alberta . 360 The Kootenay News Advertiser. 167 Abbotsford Times . 164 Westworld (BC) . 360 Kootenay Rocky Mountain Gibsons Cascade . 235 Westworld BC . 360 Visitor’s Magazine . 305 Coast Independent . 165 CFSR-FM, 107.1 mHz . 108 Westworld Saskatchewan. 360 Mining & Exploration . 313 Gold River Home Business Report . 297 Burns Lake RVWest . 338 Conuma Cable Systems . 84 Agassiz Lakes District News. 167 Shaw Cable (Cranbrook) . 85 The Gold River Record . 166 Agassiz/Harrison Observer . 164 Ski & Ride West . 342 Golden Campbell River SnoRiders West . 342 Aldergrove Campbell River Courier-Islander . 164 CKGR-AM, 1400 kHz . 112 Transitions . 350 Golden Star . 166 Aldergrove Star. 164 Campbell River Mirror . 164 TV This Week (Cranbrook) . 352 Armstrong Campbell River TV Association . 83 Grand Forks CFWB-AM, 1490 kHz . 109 Creston CKGF-AM, 1340 kHz. 112 Armstrong Advertiser . 164 Creston Valley Advance. -

Mcgill Law Journal Revuede Droitde Mcgill

McGill Revue de Law droit de Journal McGill Vol. 50 DECEMBER 2005 DÉCEMBRE No 4 SPECIAL ISSUE / NUMÉRO SPÉCIAL NAVIGATING THE TRANSSYSTEMIC TRACER LE TRANSSYSTEMIQUE Where Law and Pedagogy Meet in the Transsystemic Contracts Classroom Rosalie Jukier* In this article, the author examines how the Dans cet article, l’auteure examine comment transsystemic McGill Programme, predicated on a fonctionne «sur le terrain», dans un cours d’Obligations uniquely comparative, bilingual, and dialogic contractuelles de première année, le programme theoretical foundation of legal education, operates “on transsystémique de McGill, bâti sur des fondements the ground” in a first-year Contractual Obligations théoriques de l’éducation juridique qui sont à la fois classroom. She describes generally how the McGill comparatifs, bilingues, et dialogiques. Elle explique Programme distinguishes itself from other comparative comment, de manière générale, le programme de or interdisciplinary projects in law, through its focus on McGill se distingue d’autres projets juridiques integration rather than on sequential comparison, as comparatifs ou interdisciplinaires, de par son insistance well as its attempt to link perspectives to mentalités of sur l’intégration plutôt que sur la comparaison different traditions. The author concludes with a more séquentielle, ainsi que de par son objectif de relier les detailed study of the area of specific performance as a perspectives et mentalités propres à différentes particular application of a given legal phenomenon in traditions. L’auteure conclut avec une étude plus different systemic contexts. approfondie de la doctrine de «specific performance» en tant qu’application spécifique dans divers contextes systémiques d'un phénomène juridique donné. * Associate Professor, Faculty of Law, McGill University. -

Les Pierres Crieront !

4 • Le Devoir, samedi 2 avril 1977 L’ancien et le nouveau. éditorial Les pierres crieront ! par JEAN MARTUCCI les pierres crieront”. Je peux bien leur de — “Maître, reprends tes disciples!” Ils mander d’être moins bruyants. Ils peuvent Le Livre blanc sur la langue sont en train de passer pour des marxistes et bien se fatiguer de manifester et d animer des communistes en dénonçant avec si peu des comités des citoyens. On peut bien les Depuis qu’il est question d’une nouvelle loi tion odieuse entre citoyens natifs du Québec de nuances les abus des grosses compagnies traire, le droit de la minorité anglophone à faire taire en leur prêchant la prudence et la une existence propre et à un réseau d’institu et citoyens originaires d’ailleurs, comme si et des grandes puissances. Ils jouent un jeu sur la langue, MM. René Lévesque et Camille résignation. A la limite, d’autres que moi dangereux, tu sais. Calme-les un peu. A les Laurin ont émis à maintes reprises le voeu que tions qui en étaient l’expression logique. tous, une fois acquise la citoyenneté pour les peuvent les retirer du circuit par la prison, entendre, les pauvres et les chômeurs ont le futur régime linguistique, loin d’être une Dans le domaine économique, le libéralisme nouveaux venus, ne devaient pas être rigou l’asile ou l’excommunication. Mais, du mi toujours raison, les vieillards sont tous des source de divisions acrimonieuses, soit l’ex de la majorité avait malheureusement donné reusement égaux devant la loi. C’est aussi li lieu des champs passés au napalm, des villes oubliés, les Amérindiens et les Inuit au miter tout a fait arbitrairement l’apparte pression d’un consensus très large et un fac lieu à une véritable domination de la minorité raient le droit plus que nous tous de rester pulvérisées par les armes nucléaires et des teur de rapprochement entre Québécois d’ori à laquelle il importait de mettre un terme. -

A Legal and Epidemiological Justification for Federal Authority in Public Health Emergencies

A Legal and Epidemiological Justification for Federal Authority in Public Health Emergencies Amir Attaran & Kumanan Wilson* Federal Canada’s authority to control epidemic Les lois fédérales canadiennes relatives au contrôle disease under existing laws is seriously limited—a reality des maladies épidémiques sont faibles—ce que l’épidémie that was demonstrated in unflattering health and economic du SRAS a démontré tant bien sur le plan de la santé que terms by the SARS epidemic. Yet even Canadians who sur le plan économique. Pourtant, même les canadiens qui work in public health or medicine and who lament the œuvrent dans le domaine de la santé publique ou en federal government’s lack of statutory authority are often médecine et qui lamentent l’impuissance du gouvernement resigned to it because of an ingrained belief that the fédéral s’y résignent souvent. Cela s’explique par la Constitution Act, 1867 assigns responsibility over health to croyance inébranlable que la Loi constitutionnelle de 1867 the provinces and ties Parliament’s hands such that it cède la compétence exclusive en matière de santé aux cannot pass laws for epidemic preparedness and response. provinces, et restreint de surcroît la capacité du Parlement We show in this paper that this belief is legally wrong canadien de mener à bien l’adoption de lois fédérales en and medically undesirable. Not only does Parliament have matière de préparation et de réponse aux épidémies. the constitutional jurisdiction, mainly under the criminal Dans cet article, nous démontrons que cette croyance law and quarantine powers, to pass federal laws for est à la fois erronée sur le plan juridique et indésirable d’un epidemic preparedness and response, but current Supreme point de vue médical. -

Thesis Survey

THESES SURVEY RECENSION DES THESES I. Doctoral Theses/Theses de doctorat Ebow P. Bondzi-Simpson, The International Regulation of Relationships between Transnational Corporations and Host States: Conceptual Analyses and an Inquiry into Attempts at Codification and Control, University of Toronto In this study, a juridical examination is made of the relationships between transnational corporations (TNCs) and host states, especially developing coun- tries as hosts. It notes the positive contributions that TNCs make to host states and encourages this trend. But more especially, it notes the tensions that have existed between them and endeavours to provide legal responses that take into account the legitimate interests of these two main actors. A harmonization approach is adopted in developing the said responses. Some of the specific subjects that have received attention, and for which responses have been provided, include: the scope of the right to renegotiate investment contracts; the conditions for reference of international investment disputes to international dispute settlement machinery; closing loop-holes on transfer pricing practices; providing more certain and uniform consumer and environmental protection standards, and restricting the grounds for nationaliza- tion of foreign property and assessing appropriate compensation therefor. However, while the thesis attempts to develop some juridical responses to regulate some of the inhospitable features of foreign direct investment, it must also be pointed out that the increasingly developing country hosts are seeking to attract foreign investors on reasonable terms. Indeed, many developing coun- tries - as well as former socialist countries - are becoming market-oriented in their policies, either voluntarily or subject to domestic pressures or pressures from international business concerns or even from multilateral agencies such as the International Monetary Fund (IMF) or the International Bank for Recon- struction and Development (IBRD). -

Une Maison Exemplaire!

ENVIRONNEMENT DÉVELOPPEMENT DURABLE Thomas Mulcair Le transport par L’économique, était ministre en eau est la voie le social et 2006 et le Québec écologique des l’environnement se donnait sa loi entreprises vont de pair Page I 3 Page I 4 Page I 5 CAHIER THÉMATIQUE I › LE DEVOIR, LES SAMEDI 17 ET DIMANCHE 18 NOVEMBRE 2012 MAISON DU DÉVELOPPEMENT DURABLE Une maison exemplaire! Toutes les ressources sont mises en commun Organisme à but non lucratif distinct de ses membres fonda- teurs, la Maison du développement durable (MDD) a fêté son premier anniversaire le 6 octobre dernier et est en voie d’être le premier organisme à obtenir une certification LEED Platine en milieu urbain pour des bureaux. Robert Perreault, direc- teur de la MDD, se réjouit du succès et de l’attrait que la Mai- son crée autour du développement durable. JACINTHE LEBLANC de-chaussée, mais aussi de la présence de la Maison en l y a un an, la Maison du plein milieu du Quartier des développement durable spectacles. accueillait officiellement Le nom retenu de la Mai- ses huit membres pro- son du développement dura- priétaires et sept groupes ble se justifie si l’on consi- Ilocataires. L’idée est partie de dère qui en sont les membres la volonté, il y a une dizaine fondateurs, selon M. Per- d’années, d’offrir un environ- reault, puisque cela fait partie nement de travail sain, mais de chacun d’entre eux. Le dé- aussi de regrouper sous un veloppement doit se préoccu- même toit des groupes so- per de l’environnement, mais ciaux et environnementaux aussi «des humains, de leur ayant une perspective com- culture, de leur droit. -

Quebec' International Strategies: Mastering Globalization and New

Quebec’ international strategies: mastering globalization and new possibilities of governance Guy Lachapelle Ph.D. Concordia University Secretary General of the International Political Science Association Stéphane Paquin, Ph.D. Research Fellow International Political Science Association Paper presented at the Conference Québec and Canada in the New Century : New Dynamics, New Opportunities Queen’s University School of Policy Studies Room 202 31 October – 1 November 2003 Quebec’ international strategies: mastering globalization and new possibilities of governance The objective of this chapter is to summarize the debates and research issues related to the impact of globalization and the crisis of the nation-state and how its redefine the strategies of the Québec governments. The Québec society has become since the Second World War, and especially in the last thirty years, a more global society which simply means that Quebecers understand the importance to act not only locally but also globally. Québec governments have adopted several policies to respond to these challenges. This chapter is divided into three themes. The first theme focuses directly on the globalization debate, on its definition, on its consequences, on the transformation of the Quebec State and the international system. Clearly, globalization is redefining the political relations between Quebec, other nations, the federal government and also between the others communities within the Canadian state. The second theme looks over the issue of governance and upon the political and sociological fragmentation between Québec, as a nation, and the rest of Canada1. Globalization is expanding the set of actions of the sub-state governments and nationalist movements, such as the Parti Québécois, have in hands several means to ensure their survival as a nation. -

Derek Mckee Faculté De Droit, Université De Montréal Pavillon Maximilien-Caron C.P

Derek McKee Faculté de droit, Université de Montréal Pavillon Maximilien-Caron C.P. 6128, succ. Centre-ville Montréal, Québec H3C 3J7 (514) 343-2329 [email protected] I. BACKGROUND Academic and Professional Appointments 2018– Faculté de droit, Université de Montréal Associate Professor 2012–2018 Faculté de droit, Université de Sherbrooke Associate Professor (2018) Assistant Professor (2013–2018) Professor chargé d’enseignement (2012–2013) 2006–2007 Supreme Court of Canada Law Clerk to Chief Justice Beverley McLachlin Education 2007–2013 University of Toronto, Faculty of Law Doctor of Juridical Science (S.J.D.) Dissertation: “Internationalism and Global Governance in Canadian Public Law” Supervisor: Prof. Kerry Rittich SSHRC Canada Graduate Scholarship, 2008–2011 ($105,000) Ontario Graduate Scholarship, 2007–2008 ($15,000) University of Toronto Faculty of Law Doctoral Scholarship, 2007–2008 ($9,000) 2002–2006 McGill University, Faculty of Law Bachelor of Civil Laws/Bachelor of Laws (B.C.L./LL.B.) Dean’s Honour List Joseph Cohen, Q.C. Award, 2006 (shared) Montreal Bar Association Prize for highest standing in Civil Procedure, 2006 Daniel Mettarlin Memorial Scholarship for academic achievement and demonstrated interest in public interest advocacy, 2005 (shared) Harry Batshaw prize for the best result in the course “Foundations of Canadian Law,” 2003 English Editorial Board, McGill Law Journal, 2003–2005 1993–1998 Harvard University Bachelor of Arts magna cum laude Joint concentration in Visual and Environmental Studies and Anthropology Senior thesis: “Darshan in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction” PROF. DEREK MCKEE – CURRICULUM VITAE – UPDATED NOVEMBER 2019 1 Professional credentials Law Society of Ontario (called to the bar 2007) Languages English (native speaker), French (fluent), German (intermediate) II.