The Canadian Legal Research and Writing Guide Formerly the Best Guide to Canadian Legal Research 2018 Canliidocs 161

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

RELX Group Annual Reports and Financial Statements 2015

Annual Reports and Financial Statements 2015 Annual Reports and Financial Statements 2015 RELX Group is a world-leading provider of information and analytics for professional and business customers across industries. We help scientists make new discoveries, lawyers win cases, doctors save lives and insurance companies offer customers lower prices. We save taxpayers and consumers money by preventing fraud and help executives forge commercial relationships with their clients. In short, we enable our customers to make better decisions, get better results and be more productive. RELX PLC is a London listed holding company which owns 52.9 percent of RELX Group. RELX NV is an Amsterdam listed holding company which owns 47.1 percent of RELX Group. Forward-looking statements The Reports and Financial Statements 2015 contain forward-looking statements within the meaning of Section 27A of the US Securities Act of 1933, as amended, and Section 21E of the US Securities Exchange Act of 1934, as amended. These statements are subject to a number of risks and uncertainties that could cause actual results or outcomes to differ materially from those currently being anticipated. The terms “estimate”, “project”, “plan”, “intend”, “expect”, “should be”, “will be”, “believe”, “trends” and similar expressions identify forward-looking statements. Factors which may cause future outcomes to differ from those foreseen in forward-looking statements include, but are not limited to competitive factors in the industries in which the Group operates; demand for the Group’s products and services; exchange rate fluctuations; general economic and business conditions; legislative, fiscal, tax and regulatory developments and political risks; the availability of third-party content and data; breaches of our data security systems and interruptions in our information technology systems; changes in law and legal interpretations affecting the Group’s intellectual property rights and other risks referenced from time to time in the filings of the Group with the US Securities and Exchange Commission. -

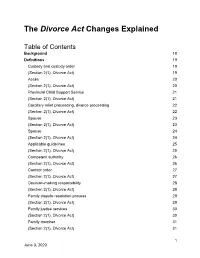

The Divorce Act Changes Explained

The Divorce Act Changes Explained Table of Contents Background 18 Definitions 19 Custody and custody order 19 (Section 2(1), Divorce Act) 19 Accès 20 (Section 2(1), Divorce Act) 20 Provincial Child Support Service 21 (Section 2(1), Divorce Act) 21 Corollary relief proceeding, divorce proceeding 22 (Section 2(1), Divorce Act) 22 Spouse 23 (Section 2(1), Divorce Act) 23 Spouse 24 (Section 2(1), Divorce Act) 24 Applicable guidelines 25 (Section 2(1), Divorce Act) 25 Competent authority 26 (Section 2(1), Divorce Act) 26 Contact order 27 (Section 2(1), Divorce Act) 27 Decision-making responsibility 28 (Section 2(1), Divorce Act) 28 Family dispute resolution process 29 (Section 2(1), Divorce Act) 29 Family justice services 30 (Section 2(1), Divorce Act) 30 Family member 31 (Section 2(1), Divorce Act) 31 1 June 3, 2020 Family violence 32 (Section 2(1), Divorce Act) 32 Legal adviser 35 (Section 2(1), Divorce Act) 35 Order assignee 36 (Section 2(1), Divorce Act) 36 Parenting order 37 (Section 2(1), Divorce Act) 37 Parenting time 38 (Section 2(1), Divorce Act) 38 Relocation 39 (Section 2(1), Divorce Act) 39 Jurisdiction 40 Two proceedings commenced on different days 40 (Sections 3(2), 4(2), 5(2) Divorce Act) 40 Two proceedings commenced on same day 43 (Sections 3(3), 4(3), 5(3) Divorce Act) 43 Transfer of proceeding if parenting order applied for 47 (Section 6(1) and (2) Divorce Act) 47 Jurisdiction – application for contact order 49 (Section 6.1(1), Divorce Act) 49 Jurisdiction — no pending variation proceeding 50 (Section 6.1(2), Divorce Act) -

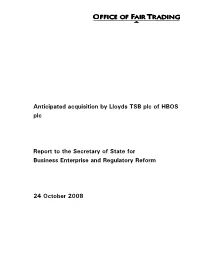

Lloyds TSB/HBOS Transaction Customers Will See Greater Continuity of HBOS Products, Services and Brands Than Would Otherwise Be the Case

Anticipated acquisition by Lloyds TSB plc of HBOS plc Report to the Secretary of State for Business Enterprise and Regulatory Reform 24 October 2008 Contents I OVERVIEW ................................................................................................ 4 Conclusions ............................................................................................... 4 Merger jurisdiction ...................................................................................... 5 Substantive competition assessment ............................................................. 5 Remedies................................................................................................... 7 Public interest consideration ......................................................................... 7 II PROCEDURAL OVERVIEW ........................................................................... 8 III PARTIES AND TRANSACTION.....................................................................10 The parties................................................................................................10 Transaction rationale ..................................................................................10 IV JURISDICTION AND LEGAL TEST ................................................................11 V THE COUNTERFACTUAL ............................................................................13 Introduction to the OFT's general approach to the counterfactual.....................13 The appropriate counterfactual in this case ...................................................14 -

The Judicial Function Under the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms Anne F Bayefsky

The Judicial Function under the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms Anne F Bayefsky* The author surveys the various American L'auteur resume les differentes theories am6- theories of judicial review in an attempt to ricaines du contr61e judiciaire dans le but de suggest approaches to a Canadian theory of sugg6rer une th6orie canadienne du r8le des the role of the judiciary under the Canadian juges sous Ia Charte canadiennedes droits et Charter of Rights and Freedoms. A detailed libert~s. Notamment, une 6tude d6taille de examination of the legislative histories of sec- 'histoire 1fgislative des articles 1, 52 et 33 de ]a Charte d6montre que les r~dacteurs ont tions 1, 52 and 33 of the Charterreveals that voulu aller au-delA de la Dclarationcana- the drafters intended to move beyond the Ca- dienne des droits et 6liminer le principe de ]a nadianBill ofRights and away from the prin- souverainet6 parlementaire. Cette intention ciple of parliamentary sovereignty. This ne se trouvant pas incorpor6e dans toute sa intention was not fully incorporated into the force au texte de Ia Charte,la protection des Charter,with the result that, properly speak- droits et libert~s au Canada n'est pas, Apro- ing, Canada's constitutional bill of rights is prement parler, o enchfiss~e )) dans ]a cons- not "entrenched". The author concludes by titution. En conclusion, l'auteur met 'accent emphasizing the establishment of a "contin- sur l'instauration d'un < colloque continu uing colloquy" involving the courts, the po- auxquels participeraient les tribunaux, les litical institutions, the legal profession and institutions politiques, ]a profession juri- society at large, in the hope that the legiti- dique et le grand public; ]a l6gitimit6 de la macy of the judicial protection of Charter protection judiciaire des droits garantis par rights will turn on the consent of the gov- la Charte serait alors fond6e sur la volont6 erned and the perceived justice of the courts' des constituants et Ia perception populaire de decisions. -

Pclaw 11.0 User Guide

© 2011 LexisNexis Practice Management Systems, Inc. All rights reserved. PCLaw® is a trademark of LexisNexis Practice Management Systems, Inc. LexisNexis, the Knowledge Burst logo, and lexis.com are registered trademarks of Reed Elsevier Properties Inc., used under license. Time Matters is a registered trademark of LexisNexis, a division of Reed Elsevier Inc. HotDocs is a registered trademark of Matthew Bender & Company, Inc. Other products and services may be trademarks or registered trademarks of their respective companies. This product contains software written by Eric Young and/or Tim Hudson. No part of this Application, Help Systems, Manuals, or related materials may be reproduced, transcribed, stored in any retrieval sys- tem, or translated into any language by any means without prior written permission of LexisNexis Practice Management Systems, Inc. Further, all users of the Application are governed by the License Agreement and Limited Warranty. Use of the Application acknowledges acceptance of the License Agreement and Limited Warranty. LexisNexis Practice Management Systems, Inc. 123 Commerce Valley Drive East Suite 310 Markham, ON L3T 7W8 Canada http://www.pclaw.com Table of Contents Installing PCLaw® ................................................................1 Written Tutorial ....................................................................19 Getting Started ...................................................................53 Working With Persons in PCLaw ......................................57 Time and Fees .....................................................................93 -

Private Law As Constitutional Context for Same-Sex Marriage

Private Law as Constitutional Context for Same-sex Marriage Private Law as Constitutional Context for Same-sex Marriage ROBERT LECKEY * While scholars of gay and lesbian activism have long eyed developments in Canada, the leading Canadian judgment on same-sex marriage has recently been catapulted into the field of vision of comparative constitutionalists indifferent to gay rights and matrimonial matters more generally. In his irate dissent in the case striking down a state sodomy law as unconstitutional, Scalia J of the United States Supreme Court mentions Halpern v Canada (Attorney General).1 Admittedly, he casts it in an unfavourable light, presenting it as a caution against the recklessness of taking constitutional protection of homosexuals too far.2 Still, one senses from at least the American literature that there can be no higher honour for a provincial judgment from Canada — if only in the jurisdictional sense — than such lofty acknowledgement that it exists. It seems fair, then, to scrutinise academic responses to the case for broader insights. And it will instantly be recognised that the Canadian judgment emerged against a backdrop of rapid change in the legislative and judicial treatment of same-sex couples in most Western jurisdictions. Following such scrutiny, this paper detects a lesson for comparative constitutional law in the scholarly treatment of the recognition of same-sex marriage in Canada. Its case study reveals a worrisome inclination to regard constitutional law, especially the judicial interpretation of entrenched rights, as an enterprise autonomous from a jurisdiction’s private law. Due respect accorded to calls for comparative constitutionalism to become interdisciplinary, comparatists would do well to attend,intra disciplinarily, to private law’s effects upon constitutional interpretation. -

CHILD SUPPORT: by JUDICIAL DECISION by LEGISLATION? (Pt

REFORM OF THE LAW CHILD SUPPORT: BY JUDICIAL DECISION BY LEGISLATION? (Pt. I) Alastair Dissett-Johnson* Dundee This isa two-partarticle. Partone analyses the recent Supreme Court ofCanada decision in Willick and the Provincial Appeal Court decisions in L6vesque and Edwards on the issue ofassessing child support. Part two examines the British Child Support Acts 1991-5, which introduced an administrative formula driven method ofassessing child support, and the Canadian Federal/Provincial Family Law Committees Report Recommendations on Child Support. The merits and problems associated with administrative andjudicial methods ofassessing child support are examined and contrasted. Il s'agit d'un article en deux parties. La première partie analyse la décision récente de la Cour suprême du Canada dans l'affaire Willick, ainsi que les décisions de la Cour d'appelprovinciale dans les affaires Lévesque etEdward qui évaluent laprotection sociale de l'enfant. La secondepartie examine, d'unepart, les Child Support Acts britanniques (Lois sur la protection sociale de l'enfant) votées de 1991 à 1995 et quiontintroduit des moyens administratifs, basés surune formule, permettant d'évaluer laprotection sociale de l'enfant et, d'autre part, le Rapport des comités sur la législationfamilialefédérale/provinciale canadienne et les recommandations concernant la protection sociale de l'enfant. Les aspects positifs et négatifsliésaux méthodesadministratives etjudiciairesd'évaluation de la protection sociale de l'enfant sont examinés. I. Introduction .... ........ -

Honours Bachelor of Producing for the Creative Industries

Honours Bachelor of Producing for the Creative Industries Applying for Ministerial Consent Under the Post-secondary Education Choice and Excellence Act, 2000 The Secretariat Postsecondary Education Quality Assessment Board 315 Front Street West 16th Floor Toronto, ON M7A 0B8 Tel.: 416-325-1686 Fax: 416-325-1711 E-mail: [email protected] sheridancollege.ca Section 1: Introduction 1.1 College and Program Information Full Legal Name of Organization: Sheridan College Institute of Technology and Advanced Learning URL for Organization Homepage (if applicable): http://www.sheridancollege.ca/ Proposed Degree Nomenclature: Honours Bachelor of Producing for the Creative Industries Location Trafalgar Campus, 1430 Trafalgar Road, Oakville, Ontario, L6H 2L1 Contact Information: Person Responsible for this submission: Name/Title: Melanie Spence-Ariemma, Provost and Vice President, Academic Full Mailing Address: 1430 Trafalgar Road, Oakville, Ontario, L6H 2L1 Telephone: (905) 845-9430 x4226 E-mail: [email protected] Name/Title: Joan Condie, Dean, Centre for Teaching and Learning Full Mailing Address: 1430 Trafalgar Road, Oakville, Ontario, L6H 2L1 Telephone: (905) 845-9430 x2559 E-mail: [email protected] Site Visit Coordinator (if different from above): Name/Title: Ashley Day, Coordinator, Program Review and Development Services Full Mailing Address: 1430 Trafalgar Road, Oakville, Ontario, L6H 2L1 Telephone: (905) 845-9430 x5561 E-mail: [email protected] Honours Bachelor of Producing for the Creative Industries -

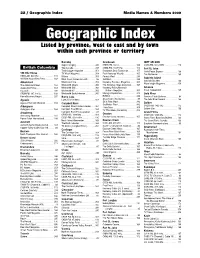

Geographic Index Media Names & Numbers 2009 Geographic Index Listed by Province, West to East and by Town Within Each Province Or Territory

22 / Geographic Index Media Names & Numbers 2009 Geographic Index Listed by province, west to east and by town within each province or territory Burnaby Cranbrook fORT nELSON Super Camping . 345 CHDR-FM, 102.9 . 109 CKRX-FM, 102.3 MHz. 113 British Columbia Tow Canada. 349 CHBZ-FM, 104.7mHz. 112 Fort St. John Truck Logger magazine . 351 Cranbrook Daily Townsman. 155 North Peace Express . 168 100 Mile House TV Week Magazine . 354 East Kootenay Weekly . 165 The Northerner . 169 CKBX-AM, 840 kHz . 111 Waters . 358 Forests West. 289 Gabriola Island 100 Mile House Free Press . 169 West Coast Cablevision Ltd.. 86 GolfWest . 293 Gabriola Sounder . 166 WestCoast Line . 359 Kootenay Business Magazine . 305 Abbotsford WaveLength Magazine . 359 The Abbotsford News. 164 Westworld Alberta . 360 The Kootenay News Advertiser. 167 Abbotsford Times . 164 Westworld (BC) . 360 Kootenay Rocky Mountain Gibsons Cascade . 235 Westworld BC . 360 Visitor’s Magazine . 305 Coast Independent . 165 CFSR-FM, 107.1 mHz . 108 Westworld Saskatchewan. 360 Mining & Exploration . 313 Gold River Home Business Report . 297 Burns Lake RVWest . 338 Conuma Cable Systems . 84 Agassiz Lakes District News. 167 Shaw Cable (Cranbrook) . 85 The Gold River Record . 166 Agassiz/Harrison Observer . 164 Ski & Ride West . 342 Golden Campbell River SnoRiders West . 342 Aldergrove Campbell River Courier-Islander . 164 CKGR-AM, 1400 kHz . 112 Transitions . 350 Golden Star . 166 Aldergrove Star. 164 Campbell River Mirror . 164 TV This Week (Cranbrook) . 352 Armstrong Campbell River TV Association . 83 Grand Forks CFWB-AM, 1490 kHz . 109 Creston CKGF-AM, 1340 kHz. 112 Armstrong Advertiser . 164 Creston Valley Advance. -

Mcgill Law Journal Revuede Droitde Mcgill

McGill Revue de Law droit de Journal McGill Vol. 50 DECEMBER 2005 DÉCEMBRE No 4 SPECIAL ISSUE / NUMÉRO SPÉCIAL NAVIGATING THE TRANSSYSTEMIC TRACER LE TRANSSYSTEMIQUE Where Law and Pedagogy Meet in the Transsystemic Contracts Classroom Rosalie Jukier* In this article, the author examines how the Dans cet article, l’auteure examine comment transsystemic McGill Programme, predicated on a fonctionne «sur le terrain», dans un cours d’Obligations uniquely comparative, bilingual, and dialogic contractuelles de première année, le programme theoretical foundation of legal education, operates “on transsystémique de McGill, bâti sur des fondements the ground” in a first-year Contractual Obligations théoriques de l’éducation juridique qui sont à la fois classroom. She describes generally how the McGill comparatifs, bilingues, et dialogiques. Elle explique Programme distinguishes itself from other comparative comment, de manière générale, le programme de or interdisciplinary projects in law, through its focus on McGill se distingue d’autres projets juridiques integration rather than on sequential comparison, as comparatifs ou interdisciplinaires, de par son insistance well as its attempt to link perspectives to mentalités of sur l’intégration plutôt que sur la comparaison different traditions. The author concludes with a more séquentielle, ainsi que de par son objectif de relier les detailed study of the area of specific performance as a perspectives et mentalités propres à différentes particular application of a given legal phenomenon in traditions. L’auteure conclut avec une étude plus different systemic contexts. approfondie de la doctrine de «specific performance» en tant qu’application spécifique dans divers contextes systémiques d'un phénomène juridique donné. * Associate Professor, Faculty of Law, McGill University. -

Familysource®

FamilySource® What’s in FamilySource® CASE LAW • Western Weekly Reports (W.W.R.) 1911- report series of other commercial • Historical Report Series publishers, including Quebec cases of FamilySource contains all full text cases dealing national importance. These law report • Alberta Law Reports (Alta. L.R.) 1908-33 with family law from the Westlaw Canada case series include: Decisions published law collection. This collection includes: • Canadian Cases on the Law of in major law report series of other Securities (C.C.L.S.) 1994-1998 commercial publishers, including • Complete coverage of reported • Canadian Intellectual Property Quebec cases of national importance. Canadian court decisions from the Reports (C.I.P.R.) 1984-90 These law report series include: common law provinces and Quebec cases of national importance, from • Canadian Reports, Appeal Cases • A.R. Alberta Reports 1986 and continuing forward (C.R.A.C.) 1871-78; 1912-13 • Alta. L.R.B.R. Alberta Labour Relations • Complete coverage of reported Supreme • Coutlee’s Canada Supreme Court Board Reports Court of Canada and Privy Council Cases (Cout. S.C.) 1875-1906 • B.C.A.C. British Columbia Appeal Cases decisions originating in any province • Eastern Law Reporter (E.L.R.) 1906-14 • C.C.C. Canadian Criminal Cases or territory from 1876 forward • Fox Patent Cases (Fox Pat.C.) 1940-71 • C.H.R.R. Canadian Human Rights Reporter • Complete coverage of Federal Court • Maritime Provinces Reports • C.I.R.B. Canada Industrial Relations Board decisions reported in the Federal Court (M.P.R.) 1929-68 • C.L.L.C. Canadian Labour Law Cases Reports from 1971 forward, and of the • New Brunswick Reports (N.B.R.) 1867-1929 Exchequer Court from 1875 through • C.L.R.B.R. -

Legal Teach-In November 10, 2016 London

Legal teach-in November 10, 2016 London 1 FORWARD-LOOKING STATEMENTS This presentation contains forward-looking statements within the meaning of Section 27A of the US Securities Act of 1933, as amended, and Section 21E of the US Securities Exchange Act of 1934, as amended. These statements are subject to a number of risks and uncertainties that could cause actual results or outcomes to differ materially from those currently being anticipated. The terms “outlook”, “estimate”, “project”, “plan”, “intend”, “expect”, “should be”, “will be”, “believe”, “trends” and similar expressions identify forward-looking statements. Factors which may cause future outcomes to differ from those foreseen in forward-looking statements include, but are not limited to competitive factors in the industries in which the Group operates; demand for the Group’s products and services; exchange rate fluctuations; general economic and business conditions; legislative, fiscal, tax and regulatory developments and political risks; the availability of third-party content and data; breaches of our data security systems and interruptions in our information technology systems; changes in law and legal interpretations affecting the Group’s intellectual property rights and other risks referenced from time to time in the filings of the Group with the US Securities and Exchange Commission. 2 1 Legal overview Mike Walsh Chief Executive Officer, Legal 3 | 4 Agenda Legal overview Mike Walsh Chief Executive Officer, Legal US legal information business Sean Fitzpatrick Managing Director,