The Judicial Function Under the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms Anne F Bayefsky

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Majoritarian Difficulty and Theories of Constitutional Decision Making

THE MAJORITARIAN DIFFICULTY AND THEORIES OF CONSTITUTIONAL DECISION MAKING Michael C. Dorf* Recent scholarship in political science and law challenges the view that judicial review in the United States poses what Alexander Bickel famously called the “counter-majoritarian difficulty.” Although courts do regularly invalidate state and federal action on constitutional grounds, they rarely depart substantially from the median of public opinion. When they do so depart, if public opinion does not eventually come in line with the judicial view, constitutional amendment, changes in judicial personnel, and/or changes in judicial doctrine typically bring judicial understandings closer to public opinion. But if the modesty of courts dissolves Bickel’s worry, it raises a distinct one: Are courts that roughly follow public opinion capable of protecting minority rights against majoritarian excesses? Do American courts, in other words, have a “majoritarian difficulty?” This Article examines that question from an interpretive perspective. It asks whether there is a normatively attractive account of the practice of judicial review that takes account of the Court’s inability to act in a strongly counter-majoritarian fashion. After highlighting difficulties with three of the leading approaches to constitutional interpretation— representation-reinforcement, originalism, and living constitutionalism—the Essay concludes that accounts of the Court as a kind of third legislative chamber fit best with its majoritarian bias. However, such third-legislative-chamber accounts rest on libertarian premises that lack universal appeal. They also lack prescriptive force, although this may be a strength: Subordinating an interpretive theory—such as representation-reinforcement, originalism, or living constitutionalism—to a view of judicial review as a form of third-legislative-chamber veto can ease the otherwise unrealistic demands for counter-majoritarianism that interpretive theories face. -

Alexander Bickel's Philosophy of Prudence

The Yale Law Journal Volume 94, Number 7, June 1985 Alexander Bickel's Philosophy of Prudence Anthony T. Kronmant INTRODUCTION Six years after Alexander Bickel's death, John Hart Ely described his former teacher and colleague as "probably the most creative constitutional theorist of the past twenty years."" Many today would concur in Ely's judgment.' Indeed, among his academic peers, Bickel is widely -regarded with a measure of respect that borders on reverence. There is, however, something puzzling about Bickel's reputation, for despite the high regard in which his work is held, Bickel has few contemporary followers.' There is, today, no Bickelian school of constitutional theory, no group of scholars working to elaborate Bickel's main ideas or even to defend them, no con- tinuing and connected body of legal writing in the intellectual tradition to which Bickel claimed allegiance. In fact, just the opposite is true. In the decade since his death, constitutional theory has turned away from the ideas that Bickel championed, moving in directions he would, I believe, f Professor of Law, Yale Law School. 1. J. ELY, DEMOCRACY AND DISTRUST 71 (1980). 2. See B. SCHMIDT, HISTORY OF THE SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES: THE JUDICI- ARY AND RESPONSIBLE GOVERNMENT 1910-21 (pt. 2) 722 (1984) (describing Bickel as "the most brilliant and influential constitutional scholar of the generation that came of age during the era of the Warren Court"); Ackerman, The Storrs Lectures: Discovering the Constitution, 93 YALE L.J. 1013, 1014 (Bickel "revered as spokesman-in-chief for a school of thought that emphasizes the importance of judicial restraint"). -

Network Map of Knowledge And

Humphry Davy George Grosz Patrick Galvin August Wilhelm von Hofmann Mervyn Gotsman Peter Blake Willa Cather Norman Vincent Peale Hans Holbein the Elder David Bomberg Hans Lewy Mark Ryden Juan Gris Ian Stevenson Charles Coleman (English painter) Mauritz de Haas David Drake Donald E. Westlake John Morton Blum Yehuda Amichai Stephen Smale Bernd and Hilla Becher Vitsentzos Kornaros Maxfield Parrish L. Sprague de Camp Derek Jarman Baron Carl von Rokitansky John LaFarge Richard Francis Burton Jamie Hewlett George Sterling Sergei Winogradsky Federico Halbherr Jean-Léon Gérôme William M. Bass Roy Lichtenstein Jacob Isaakszoon van Ruisdael Tony Cliff Julia Margaret Cameron Arnold Sommerfeld Adrian Willaert Olga Arsenievna Oleinik LeMoine Fitzgerald Christian Krohg Wilfred Thesiger Jean-Joseph Benjamin-Constant Eva Hesse `Abd Allah ibn `Abbas Him Mark Lai Clark Ashton Smith Clint Eastwood Therkel Mathiassen Bettie Page Frank DuMond Peter Whittle Salvador Espriu Gaetano Fichera William Cubley Jean Tinguely Amado Nervo Sarat Chandra Chattopadhyay Ferdinand Hodler Françoise Sagan Dave Meltzer Anton Julius Carlson Bela Cikoš Sesija John Cleese Kan Nyunt Charlotte Lamb Benjamin Silliman Howard Hendricks Jim Russell (cartoonist) Kate Chopin Gary Becker Harvey Kurtzman Michel Tapié John C. Maxwell Stan Pitt Henry Lawson Gustave Boulanger Wayne Shorter Irshad Kamil Joseph Greenberg Dungeons & Dragons Serbian epic poetry Adrian Ludwig Richter Eliseu Visconti Albert Maignan Syed Nazeer Husain Hakushu Kitahara Lim Cheng Hoe David Brin Bernard Ogilvie Dodge Star Wars Karel Capek Hudson River School Alfred Hitchcock Vladimir Colin Robert Kroetsch Shah Abdul Latif Bhittai Stephen Sondheim Robert Ludlum Frank Frazetta Walter Tevis Sax Rohmer Rafael Sabatini Ralph Nader Manon Gropius Aristide Maillol Ed Roth Jonathan Dordick Abdur Razzaq (Professor) John W. -

Is Qualified Immunity Unlawful?

Is Qualified Immunity Unlawful? William Baude* The doctrine of qualified immunity operates as an unwritten defense to civil rights lawsuits brought under 42 U.S.C. § 1983. It prevents plaintiffs from recovering damages for violations of their constitutional rights unless a government official violated “clearly established law,” which usually requires specific precedent on point. This Article argues that the qualified immunity doctrine is unlawful and inconsistent with conventional principles of statutory interpretation. Members of the Supreme Court have offered three different justifications for imposing this unwritten defense on the text of Section 1983. First, that the doctrine of qualified immunity derives from a common-law “good-faith” defense. Second, that it compensates for an earlier putative mistake in broadening the statute. Third, that it provides “fair warning” to government officials, akin to the rule of lenity. On closer examination, each of these justifications falls apart for a mix of historical, conceptual, and doctrinal reasons. There was no such defense; there was no such mistake; lenity ought not apply. Furthermore, even if these things were otherwise, the doctrine of qualified immunity would not be the best response. DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.15779/Z38MG7FV8G Copyright © 2018 California Law Review, Inc. California Law Review, Inc. (CLR) is a California nonprofit corporation. CLR and the authors are solely responsible for the content of their publications. * Neubauer Family Assistant Professor of Law, University of -

The Originalism That Was, and the One That Will Be

GREVE (DO NOT DELETE) 3/28/2013 10:11 AM The Originalism That Was, and the One That Will Be Michael S. Greve* INTRODUCTION The original title for the conference talk on which this brief article is based, hand-picked by the excellent Jack Balkin, was, “What Was Originalism.” While characteristically clever and provocative, the suggestion of originalism’s death captures my position only imperfectly. I believe that originalism—in a broad, generic sense, encompassing any belief that the text is the baseline and that its authors’ expectations count for something—will become more orthodox than ever. And, like many participants at Jack’s wonderful conference, I suspect that his Living Originalism1 will hasten that trend: already, originalism’s conservative sentinels have predictably attempted to pocket the “originalism” part and to dismiss the “living” elements.2 However, a certain kind of conservative originalism, or perhaps several positions in originalism’s “logical space,”3 has or have become unsustainable—partly for theoretical, academic reasons, but in much larger part on account of changes in the broader political context in which originalism operates. Originalism will live, but its dominant forms will have a different tone and orientation. The originalism that in my estimation has outlived its usefulness has three central, interrelated features. First, it is Court-centered and preoccupied with legal interpretation. Second, it is positivist: judges must follow the constitutional rules because they are what they are and because the 1788 sovereign said so; any talk about why he, or we, or she the people said so is for interpretive purposes off limits. -

The Canadian Legal Research and Writing Guide Formerly the Best Guide to Canadian Legal Research 2018 Canliidocs 161

The Canadian Legal Research and Writing Guide Formerly the Best Guide to Canadian Legal Research 2018 CanLIIDocs 161 Edited by Melanie Bueckert, André Clair, Maryvon Côté, Yasmin Khan, and Mandy Ostick, based on work by Catherine Best, 2018 The Canadian Legal Research and Writing Guide is based on The Best Guide to Canadian Legal Research, An online legal research guide written and published by Catherine Best, which she started in 1998. The site grew out of Catherine’s experience teaching legal research and writing, and her conviction that a process-based analytical 2018 CanLIIDocs 161 approach was needed. She was also motivated to help researchers learn to effectively use electronic research tools. Catherine Best retired In 2015, and she generously donated the site to CanLII to use as our legal research site going forward. As Best explained: The world of legal research is dramatically different than it was in 1998. However, the site’s emphasis on research process and effective electronic research continues to fill a need. It will be fascinating to see what changes the next 15 years will bring. The text has been updated and expanded for this publication by a national editorial board of legal researchers: Melanie Bueckert legal research counsel with the Manitoba Court of Appeal in Winnipeg. She is the co-founder of the Manitoba Bar Association’s Legal Research Section, has written several legal textbooks, and is also a contributor to Slaw.ca. André Clair was a legal research officer with the Court of Appeal of Newfoundland and Labrador between 2010 and 2013. He is now head of the Legal Services Division of the Supreme Court of Newfoundland and Labrador. -

The Secret Life of the Political Question Doctrine

Georgetown University Law Center Scholarship @ GEORGETOWN LAW 2004 The Secret Life of the Political Question Doctrine Louis Michael Seidman Georgetown University Law Center, [email protected] This paper can be downloaded free of charge from: https://scholarship.law.georgetown.edu/facpub/563 37 J. Marshall L. Rev. 441-480 (2004) This open-access article is brought to you by the Georgetown Law Library. Posted with permission of the author. Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.georgetown.edu/facpub Part of the Constitutional Law Commons, Jurisprudence Commons, and the Law and Politics Commons THE SECRET LIFE OF THE POLITICAL QUESTION DOCTRINE LOUIS MICHAEL SEIDMAN· "Questions, in their nature political, or which are, by the constitution and laws, submitted to the executive, can never be . made in this court."l The irony, of course, is that Marbury v. Madison, itself, "made" a political question, and the answer the Court gave was deeply political as well. As everyone reading this essay knows, the case arose out of a bitter political controversy,2 and the opinion for the Court was a carefully crafted political document-"a masterwork of indirection," according to Robert McCloskey's well known characterization, "a brilliant example of Chief Justice Marshall's capacity to sidestep danger while seemingly to court it, to advance in one direction while his opponents are looking in another. ,,3 The purpose of this essay is to explore the many layers of this irony. I will argue that despite all of the premature reports of its demise, the political question doctrine is as central to modern • Professor of Law, Georgetown University Law Center. -

American Liberals and Judicial Activism: Alexander Bickel's Appeal from the New to the Old

Indiana Law Journal Volume 51 Issue 4 Article 3 Spring 1976 American Liberals and Judicial Activism: Alexander Bickel's Appeal from the New to the Old Maurice J. Holland Indiana University School of Law Follow this and additional works at: https://www.repository.law.indiana.edu/ilj Part of the Judges Commons, Jurisprudence Commons, and the Law and Politics Commons Recommended Citation Holland, Maurice J. (1976) "American Liberals and Judicial Activism: Alexander Bickel's Appeal from the New to the Old," Indiana Law Journal: Vol. 51 : Iss. 4 , Article 3. Available at: https://www.repository.law.indiana.edu/ilj/vol51/iss4/3 This Essay is brought to you for free and open access by the Law School Journals at Digital Repository @ Maurer Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Indiana Law Journal by an authorized editor of Digital Repository @ Maurer Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Review Essay American Liberals and Judicial Activism: Alexander Bickel's Appeal from the New to the Old MAURICE J. HOLLAND* I. Before his death in November 1974, Alexander Bickel ranked among the handful of American legal scholars who could fairly be described as men of letters.' This was more than a matter of the lucid and elegant prose in which, in contributions to Ne~w Republic and Comn- mentary over the span of two decades, he illuminated a remarkably various range of subjects. That Bickel attained to more than conven- tional professional eminence in his academic speciality of constitutional law was most owing to the extraordinary breadth of conception he brought to that pursuit. -

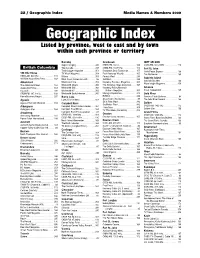

Geographic Index Media Names & Numbers 2009 Geographic Index Listed by Province, West to East and by Town Within Each Province Or Territory

22 / Geographic Index Media Names & Numbers 2009 Geographic Index Listed by province, west to east and by town within each province or territory Burnaby Cranbrook fORT nELSON Super Camping . 345 CHDR-FM, 102.9 . 109 CKRX-FM, 102.3 MHz. 113 British Columbia Tow Canada. 349 CHBZ-FM, 104.7mHz. 112 Fort St. John Truck Logger magazine . 351 Cranbrook Daily Townsman. 155 North Peace Express . 168 100 Mile House TV Week Magazine . 354 East Kootenay Weekly . 165 The Northerner . 169 CKBX-AM, 840 kHz . 111 Waters . 358 Forests West. 289 Gabriola Island 100 Mile House Free Press . 169 West Coast Cablevision Ltd.. 86 GolfWest . 293 Gabriola Sounder . 166 WestCoast Line . 359 Kootenay Business Magazine . 305 Abbotsford WaveLength Magazine . 359 The Abbotsford News. 164 Westworld Alberta . 360 The Kootenay News Advertiser. 167 Abbotsford Times . 164 Westworld (BC) . 360 Kootenay Rocky Mountain Gibsons Cascade . 235 Westworld BC . 360 Visitor’s Magazine . 305 Coast Independent . 165 CFSR-FM, 107.1 mHz . 108 Westworld Saskatchewan. 360 Mining & Exploration . 313 Gold River Home Business Report . 297 Burns Lake RVWest . 338 Conuma Cable Systems . 84 Agassiz Lakes District News. 167 Shaw Cable (Cranbrook) . 85 The Gold River Record . 166 Agassiz/Harrison Observer . 164 Ski & Ride West . 342 Golden Campbell River SnoRiders West . 342 Aldergrove Campbell River Courier-Islander . 164 CKGR-AM, 1400 kHz . 112 Transitions . 350 Golden Star . 166 Aldergrove Star. 164 Campbell River Mirror . 164 TV This Week (Cranbrook) . 352 Armstrong Campbell River TV Association . 83 Grand Forks CFWB-AM, 1490 kHz . 109 Creston CKGF-AM, 1340 kHz. 112 Armstrong Advertiser . 164 Creston Valley Advance. -

Mcgill Law Journal Revuede Droitde Mcgill

McGill Revue de Law droit de Journal McGill Vol. 50 DECEMBER 2005 DÉCEMBRE No 4 SPECIAL ISSUE / NUMÉRO SPÉCIAL NAVIGATING THE TRANSSYSTEMIC TRACER LE TRANSSYSTEMIQUE Where Law and Pedagogy Meet in the Transsystemic Contracts Classroom Rosalie Jukier* In this article, the author examines how the Dans cet article, l’auteure examine comment transsystemic McGill Programme, predicated on a fonctionne «sur le terrain», dans un cours d’Obligations uniquely comparative, bilingual, and dialogic contractuelles de première année, le programme theoretical foundation of legal education, operates “on transsystémique de McGill, bâti sur des fondements the ground” in a first-year Contractual Obligations théoriques de l’éducation juridique qui sont à la fois classroom. She describes generally how the McGill comparatifs, bilingues, et dialogiques. Elle explique Programme distinguishes itself from other comparative comment, de manière générale, le programme de or interdisciplinary projects in law, through its focus on McGill se distingue d’autres projets juridiques integration rather than on sequential comparison, as comparatifs ou interdisciplinaires, de par son insistance well as its attempt to link perspectives to mentalités of sur l’intégration plutôt que sur la comparaison different traditions. The author concludes with a more séquentielle, ainsi que de par son objectif de relier les detailed study of the area of specific performance as a perspectives et mentalités propres à différentes particular application of a given legal phenomenon in traditions. L’auteure conclut avec une étude plus different systemic contexts. approfondie de la doctrine de «specific performance» en tant qu’application spécifique dans divers contextes systémiques d'un phénomène juridique donné. * Associate Professor, Faculty of Law, McGill University. -

95Th Annual Honors Convocation

95TH ANNUAL HONORS CONVOCATION MARCH 18, 2018 2:00 P.M. HILL AUDITORIUM This year marks the 95th Honors Convocation held at the University of Michigan since the first was instituted on May 13, 1924, by President Marion LeRoy Burton. On these occasions, the University publicly recognizes and commends the undergraduate students in its schools and colleges who have earned distinguished academic records or have excelled as leaders in the community. It is with great pride that the University honors those students who have most clearly and effectively demonstrated academic excellence, dynamic leadership, and inspirational volunteerism. The Honors Convocation ranks with the Commencement Exercises as among the most important ceremonies of the University year. The names of the students who are honored for outstanding achievement this year appear in this program. They include all students who have earned University Honors in both Winter 2017 and Fall 2017, plus all seniors who have earned University Honors in either Winter 2017 or Fall 2017. The William J. Branstrom Freshman Prize recipients are listed, as well—recognizing first year undergraduate students whose academic achievement during their first semester on campus place them in the upper five percent of their school or college class. James B. Angell Scholars—students who receive all “A” grades over consecutive terms—are given a special place in the program. In addition, the student speaker is recognized individually for exemplary contributions to the University community. To all honored students, and to their parents, the University extends its hearty congratulations. Martin A. Philbert • Provost and Executive Vice President for Academic Affairs Honored Students Honored Faculty Faculty Colleagues and Friends of the University It is a pleasure to welcome you to the 95th University of Michigan Honors Convocation. -

A Legal and Epidemiological Justification for Federal Authority in Public Health Emergencies

A Legal and Epidemiological Justification for Federal Authority in Public Health Emergencies Amir Attaran & Kumanan Wilson* Federal Canada’s authority to control epidemic Les lois fédérales canadiennes relatives au contrôle disease under existing laws is seriously limited—a reality des maladies épidémiques sont faibles—ce que l’épidémie that was demonstrated in unflattering health and economic du SRAS a démontré tant bien sur le plan de la santé que terms by the SARS epidemic. Yet even Canadians who sur le plan économique. Pourtant, même les canadiens qui work in public health or medicine and who lament the œuvrent dans le domaine de la santé publique ou en federal government’s lack of statutory authority are often médecine et qui lamentent l’impuissance du gouvernement resigned to it because of an ingrained belief that the fédéral s’y résignent souvent. Cela s’explique par la Constitution Act, 1867 assigns responsibility over health to croyance inébranlable que la Loi constitutionnelle de 1867 the provinces and ties Parliament’s hands such that it cède la compétence exclusive en matière de santé aux cannot pass laws for epidemic preparedness and response. provinces, et restreint de surcroît la capacité du Parlement We show in this paper that this belief is legally wrong canadien de mener à bien l’adoption de lois fédérales en and medically undesirable. Not only does Parliament have matière de préparation et de réponse aux épidémies. the constitutional jurisdiction, mainly under the criminal Dans cet article, nous démontrons que cette croyance law and quarantine powers, to pass federal laws for est à la fois erronée sur le plan juridique et indésirable d’un epidemic preparedness and response, but current Supreme point de vue médical.