Metaphor and Metanoia: Linguistic Transfer and Cognitive Transformation in British and Irish Modernism

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Roth Book Notes--Mcluhan.Pdf

Book Notes: Reading in the Time of Coronavirus By Jefferson Scholar-in-Residence Dr. Andrew Roth Mediated America Part Two: Who Was Marshall McLuhan & What Did He Say? McLuhan, Marshall. The Mechanical Bride: Folklore of Industrial Man. (New York: Vanguard Press, 1951). McLuhan, Marshall and Bruce R. Powers. The Global Village: Transformations in World Life and Media in the 21st Century. (New York: Oxford University Press, 1989). McLuhan, Marshall. The Gutenberg Galaxy: The Making of Typographic Man. (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1962). McLuhan, Marshall. Understanding Media: The Extensions of Man. (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1994. Originally Published 1964). The Mechanical Bride: The Gutenberg Galaxy Understanding Media: The Folklore of Industrial Man by Marshall McLuhan Extensions of Man by Marshall by Marshall McLuhan McLuhan and Lewis H. Lapham Last week in Book Notes, we discussed Norman Mailer’s discovery in Superman Comes to the Supermarket of mediated America, that trifurcated world in which Americans live simultaneously in three realms, in three realities. One is based, more or less, in the physical world of nouns and verbs, which is to say people, other creatures, and things (objects) that either act or are acted upon. The second is a world of mental images lodged between people’s ears; and, third, and most importantly, the mediasphere. The mediascape is where the two worlds meet, filtering back and forth between each other sometimes in harmony but frequently in a dissonant clanging and clashing of competing images, of competing cultures, of competing realities. Two quick asides: First, it needs to be immediately said that Americans are not the first ever and certainly not the only 21st century denizens of multiple realities, as any glimpse of Japanese anime, Chinese Donghua, or British Cosplay Girls Facebook page will attest, but Americans first gave it full bloom with the “Hollywoodization,” the “Disneyfication” of just about anything, for when Mae West murmured, “Come up and see me some time,” she said more than she could have ever imagined. -

Works on Giambattista Vico in English from 1884 Through 2009

Works on Giambattista Vico in English from 1884 through 2009 COMPILED BY MOLLY BLA C K VERENE TABLE OF CON T EN T S PART I. Books A. Monographs . .84 B. Collected Volumes . 98 C. Dissertations and Theses . 111 D. Journals......................................116 PART II. Essays A. Articles, Chapters, et cetera . 120 B. Entries in Reference Works . 177 C. Reviews and Abstracts of Works in Other Languages ..180 PART III. Translations A. English Translations ............................186 B. Reviews of Translations in Other Languages.........192 PART IV. Citations...................................195 APPENDIX. Bibliographies . .302 83 84 NEW VICO STUDIE S 27 (2009) PART I. BOOKS A. Monographs Adams, Henry Packwood. The Life and Writings of Giambattista Vico. London: Allen and Unwin, 1935; reprinted New York: Russell and Russell, 1970. REV I EWS : Gianturco, Elio. Italica 13 (1936): 132. Jessop, T. E. Philosophy 11 (1936): 216–18. Albano, Maeve Edith. Vico and Providence. Emory Vico Studies no. 1. Series ed. D. P. Verene. New York: Peter Lang, 1986. REV I EWS : Daniel, Stephen H. The Eighteenth Century: A Current Bibliography, n.s. 12 (1986): 148–49. Munzel, G. F. New Vico Studies 5 (1987): 173–75. Simon, L. Canadian Philosophical Reviews 8 (1988): 335–37. Avis, Paul. The Foundations of Modern Historical Thought: From Machiavelli to Vico. Beckenham (London): Croom Helm, 1986. REV I EWS : Goldie, M. History 72 (1987): 84–85. Haddock, Bruce A. New Vico Studies 5 (1987): 185–86. Bedani, Gino L. C. Vico Revisited: Orthodoxy, Naturalism and Science in the ‘Scienza nuova.’ Oxford: Berg, 1989. REV I EWS : Costa, Gustavo. New Vico Studies 8 (1990): 90–92. -

What Cant Be Coded Can Be Decorded Reading Writing Performing Finnegans Wake

ORBIT - Online Repository of Birkbeck Institutional Theses Enabling Open Access to Birkbecks Research Degree output What cant be coded can be decorded Reading Writing Performing Finnegans Wake http://bbktheses.da.ulcc.ac.uk/198/ Version: Public Version Citation: Evans, Oliver Rory Thomas (2016) What cant be coded can be decorded Reading Writing Performing Finnegans Wake. PhD thesis, Birkbeck, University of London. c 2016 The Author(s) All material available through ORBIT is protected by intellectual property law, including copyright law. Any use made of the contents should comply with the relevant law. Deposit guide Contact: email “What can’t be coded can be decorded” Reading Writing Performing Finnegans Wake Oliver Rory Thomas Evans Phd Thesis School of Arts, Birkbeck College, University of London (2016) 2 3 This thesis examines the ways in which performances of James Joyce’s Finnegans Wake (1939) navigate the boundary between reading and writing. I consider the extent to which performances enact alternative readings of Finnegans Wake, challenging notions of competence and understanding; and by viewing performance as a form of writing I ask whether Joyce’s composition process can be remembered by its recomposition into new performances. These perspectives raise questions about authority and archivisation, and I argue that performances of Finnegans Wake challenge hierarchical and institutional forms of interpretation. By appropriating Joyce’s text through different methodologies of reading and writing I argue that these performances come into contact with a community of ghosts and traces which haunt its composition. In chapter one I argue that performance played an important role in the composition and early critical reception of Finnegans Wake and conduct an overview of various performances which challenge the notion of a ‘Joycean competence’ or encounter the text through radical recompositions of its material. -

Fundamentalist Journal, Volume 2, Number 7

Liberty University DigitalCommons@Liberty University 1983 The undF amentalist Journal 7-1983 Fundamentalist Journal, Volume 2, Number 7 Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.liberty.edu/fun_83 Recommended Citation "Fundamentalist Journal, Volume 2, Number 7" (1983). 1983. Paper 1. http://digitalcommons.liberty.edu/fun_83/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the The undF amentalist Journal at DigitalCommons@Liberty University. It has been accepted for inclusion in 1983 by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@Liberty University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. TUNDAI"IENTALI.ET One Dollqr & Ninety-Five Cents JOUPNAL Jtrly/August 1983 OneNation underGod on the Rebound The Churchand Her Rights The Christian Churchunder Communism America WakeUp! I .r'-, v |<(,*,, ! {, ()L/ ( I {! t1 v *'e ';;il l-,rl llL. (; c:h:r{r "rj Fr It U, j/ e/ +- -<-r-o z,o 3,;S L <-l Fj (^l o3 i" t' f.l cm ::r !^-.,.. a^ uci r! tJ , -o aq; -a ,i >! iJ.l vm a*j Nt- 5T T Have you ever wondered why Christians are usually portrayed unsympatheticallyon TV and in movies? . Why our childrenare learning anti- Christiarrmoral valuesin public schools? . Why so few Christianbooks.rre in your localbookstore and library-even when they are bestsellers? V,lhy? Bacnusethcrc's {t ttcTLtlt)ltltc of cettsorshilt sTLteepifigArtrcrica. No, it's not the obvious kind that actuallybr-rrns books. It's somethirrg much more subtle-and more effective. The real censorstodav are hard-coresecu- laristswhtl hold the p.,siti.,nsof influence in education,the media, and public life. -

Abbott, C.S. 1978. Marianne Moore: a Reference Guide

Abbott, C.S. 1978. Marianne Moore: A Reference Guide. Boston: G.K. Hall & Co. Abrams, M.H. 1953. The Mirror and the Lamp: Romantic Theory and the Critical Tradition. Oxford: Oxford U P. Abrams, M.H. 1971. Natural Supernaturalism: Tradition and Revolution in Romantic Literature. New York: W.W. Norton. Abrams, M.H. 1984. The Correspondent Breeze: Essays on English Romanticism. New York: W.W. Norton. Abrams, M.H. 1989. Doing Things With Texts: Essays in Criticism and Critical Theory. Ed. M. Fischer. New York: W.W. Norton. Ackerman, D. 1990. A Natural History of the Senses. New York: Random House. Adams, H. 1928. The Tendency of History. New York: MacMillan. Adams, H. 1964. The Education of Henry Adams. Two Volumes. New York: Time Incorporated. Adams, H. 1983. Philosophy of the Literary Symbolic. Tallahassee, FL: University Presses of Florida. Adams, H. 1971, ed. Critical Theory Since Plato. New York: Harcourt, Brace Jovanovich. Adams, H., ed. 1986. Critical Theory Since 1965. Tallahassee, FL: University Presses of Florida. Adams, H.P. 1935. The Life and Writings of Giambattista Vico. London: George Allen & Unwin. Adams, J. 1984. Yeats and the Masks of Syntax. New York: Columbia U P. Adams, S. 1997. Poetic Designs: An Introduction to Meters, Verse Forms, and Figures of Speech. Peterborough, ONT: Broadview Press. Addonizio, K. 1999. Ordinary Genius: A Guide for the Poet Within. New York: W.W. Norton. Addonizio, K. and D. Laux. 1997. The Poet's Companion: A Guide to the Pleasures of Writing Poetry. New York: W.W. Norton. Aland Jr., A. 1973. Evolution and Human Behavior: An Introduction to Darwinian Anthropology. -

The Sichuan Avant-Garde, 1982-1992

China’s Second World of Poetry: The Sichuan Avant-Garde, 1982-1992 by Michael Martin Day Digital Archive for Chinese Studies (DACHS) The Sinological Library, Leiden University 2005 2 Table of Contents Acknowledgements ............................................................................................................4 Preface …………………..………………………………………………………………..7 Chapter 1: Avant-Garde Poetry Nationwide – A Brief Overview ……………..……18 Chapter 2: Zhou Lunyou: Underground Poetry during the 1970s ………………… 35 Chapter 3: The Born-Again Forest : An Early Publication …………….…………….46 Chapter 4: Macho Men or Poets Errant? ……………………………………………..79 Poetry on University Campuses………………………………………….79 A Third Generation………………………………………………………82 Hu Dong, Wan Xia, and Macho Men……………………………………88 Li Yawei………………………………………………………………….99 Ma Song………………………………………………………………...103 Finishing with University………………………………………………107 Chapter 5: A Confluence of Interests: The Institution of the Anti-Institutional ….114 Setting the Scene………………………………………………………..114 The Establishment of the Sichuan Young Poets Association…………..123 The First Product of the Association: Modernists Federation………….130 Chapter 6: The Poetry of Modernists Federation ……………………………………136 Chapter 7: Make It New and Chinese Contemporary Experimental Poetry ….…..…169 Growing Ties and a Setback……………………………………………170 Day By Day Make It New and the Makings of an Unofficial Avant-Garde Polemic…………....180 Experimental Poetry : A Final Joint Action…………………………….195 Chapter 8: Moving into the Public Eye: A Grand Exhibition -

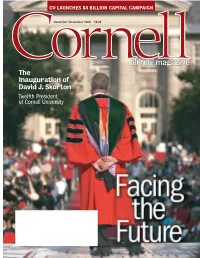

Alumni Magazine the Inauguration of David J

c1,c2,p1,c3,c4CAMND06 10/19/06 2:22 PM Page c1 CU LAUNCHES $4 BILLION CAPITAL CAMPAIGN November/December 2006 $6.00 alumni magazine The Inauguration of David J. Skorton Twelfth President of Cornell University c1,c2,p1,c3,c4CAMND06 10/19/06 4:00 PM Page c2 c1,c2,p1,c3,c4CAMND06 10/19/06 4:00 PM Page 1 002-003CAMND06toc 10/16/06 3:45 PM Page 2 Contents NOVEMBER / DECEMBER 2006 VOLUME 109 NUMBER 3 4 Letter From Ithaca alumni magazine French toast Features 6 Correspondence Natural selection 10 From the Hill The dawn of the campaign. Plus: Milstein Hall 3.0, meeting the Class of 2010, the ranking file, the Creeper pleads, and a new divestment movement. 16 Sports A rink renewed 18 Authors The full Marcham 35 Finger Lakes Marketplace 52 44 Wines of the Finger Lakes 46 In Our Own Words 2005 Lucas Cabernet Franc CAROL KAMMEN “Limited Reserve” To Cornell historian Carol Kammen, 62 Classifieds & Cornellians the unheard voices in the University’s in Business story belong to the students them- selves. So the senior lecturer dug into 65 Alma Matters the vaults of the Kroch Library and unearthed a trove of diaries, scrap- books, letters, and journals written by 68 Class Notes undergraduates from the founding to 109 the present.Their thoughts—now 46 assembled into a book, First-Person Alumni Deaths Cornell—reveal how the anxieties, 112 distractions, and preoccupations of students on the Hill have (and haven’t) changed since 1868.We offer some excerpts. Cornelliana Authority figures 52 Rhapsody in Red JIM ROBERTS ’71 112 The inauguration of David Skorton -

“Ways of Staying”

“WAYS OF STAYING” PARADOX AND DISLOCATION IN THE POSTCOLONY Kevin Jon Bloom A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Humanities, University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, in fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Creative Writing. Johannesburg, 2009 1 Declaration I declare that this thesis is my own unaided work. It is submitted for the degree of Master of Arts in the University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg. It has not been submitted for any other degree or examination in any other university. ---------------------------- Kevin Jon Bloom Twelfth day of February, 2009. 2 Abstract The first section of the thesis is a narrative non-fiction book-length work titled Ways of Staying , which is to be published by Picador Africa in May 2009 and is a journey through selected public and private concerns of contemporary South African life. Written in the first-person, it seeks to give the reader an intimate view of some of the more significant headlines of the past two years – the David Rattray murder, the ANC Polokwane conference, the xenophobic attacks, to name just a few – and to intersperse these with personal accounts of the fallout from violent crime (the author’s cousin Richard Bloom was murdered in a high-profile attack in 2006). The objective of the book is to present in a non-solution orientated (or heuristic) manner the various textures and paradoxes of a complicated country. The second section of the thesis is a reflexive essay on the above, where Ways of Staying is located within a range of thematic and symbolic influences, specifically: the work of novelist VS Naipaul vis-à-vis the parallel and incongruous dislocation of self and other in the post-colony; the work of Alan Paton, JM Coetzee and Rian Malan vis-à-vis the theme of ‘fear’ as a dominant force in white South African writing; and the non-fiction work of Antjie Krog vis-à-vis race and identity in a post- apartheid context. -

Was Mcluhan a Semiotician?

MediaTropes eJournal Vol I (2008): 113–126 ISSN 1913-6005 THE MEDIUM IS THE SIGN: WAS MCLUHAN A SEMIOTICIAN? MARCEL DANESI That the world is being threatened more and more by those who hold the levers of “media power,” i.e., by those who control television networks, movie production studios, and computer media, is obvious to virtually everyone. It was, of course, Marshall McLuhan who was among the first to emphasize this fact, showing how the “meaning structures” that the media produce shape human cognition. The interesting thing for a semiotician is that he did so in a way that is consistent with semiotic ideas and, above all else, semiotic method. Was McLuhan a semiotician? Of course, he never claimed to be one, and, whether he knew anything about semiotic theory as such is beside the point. It is not commonly known outside of semiotics proper that the “science of signs” grew out of attempts by the first physicians of the Western world to understand how the body and the mind interact within specific cultural domains. Indeed, in its oldest usage, the term semiotics was applied to the study of the observable pattern of physiological symptoms induced by particular diseases. Hippocrates (460?–377? BCE)—the founder of Western medical science—viewed the ways in which an individual in a specific culture would manifest and relate the symptomatology associated with a disease as the basis upon which to carry out an appropriate diagnosis and then to formulate a suitable prognosis. The physician Galen of Pergamum (130?–200? CE) similarly referred to diagnosis as a process of semiosis. -

Marshall Mcluhan and Higher Music Education Glen Carruthers

Document generated on 09/27/2021 5:34 p.m. Intersections Canadian Journal of Music Revue canadienne de musique --> See the erratum for this article Marshall Mcluhan and Higher Music Education Glen Carruthers Volume 36, Number 2, 2016 Article abstract The way in which Marshall McLuhan’s theories relate to teaching and learning URI: https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/1051593ar broadly has garnered scholarly attention. It is surprising, though, given his DOI: https://doi.org/10.7202/1051593ar impact on Schafer and others, that there is scant critical commentary on the implications of McLuhan’s theories for either mass music or higher music See table of contents education. The present study is a step towards redressing this gap. The study concludes that McLuhan’s iconoclastic views have direct bearing on formal learning environments, like music schools, that struggle with notions of Publisher(s) inclusivity and exclusivity, community music and concert music, improvisation and textual interpretation, even as they embrace timely and Canadian University Music Society / Société de musique des universités sweeping curricular reform. canadiennes ISSN 1911-0146 (print) 1918-512X (digital) Explore this journal Cite this article Carruthers, G. (2016). Marshall Mcluhan and Higher Music Education. Intersections, 36(2), 3–11. https://doi.org/10.7202/1051593ar Copyright © Canadian University Music Society / Société de musique des This document is protected by copyright law. Use of the services of Érudit universités canadiennes, 2018 (including reproduction) is subject to its terms and conditions, which can be viewed online. https://apropos.erudit.org/en/users/policy-on-use/ This article is disseminated and preserved by Érudit. -

Sept 02, 2013 | Critic.Co.Nz Live Entertainment From

Issue 21 | Sept 02, 2013 | critic.co.nz live entertainment from + THE KAIKORAI BAVARIAN BAND, TWO CARTOONS, MATT LANGLEY, THE PROPHET HENS, and PIPSY! + food & brew seminars from top industry gurus STUDENT TICKETS = $19.90 EDITOR Sam McChesney DePUTY EDITOR Zane Pocock SUB EDITOR Sarah Macindoe TeCHNICAL EDITOR 24 Sam Clark FEATURE DesIGNER 24 | Blood Donation and Gay Probation Daniel Blackball If those filthy Aussies can have equitable blood donation laws, why can’t we? Dr. Nick takes a look AD DESIGNER at the barriers to blood donation that gay men still face in New Zealand today. Nick Guthrie FEATURE WRITER Ines Shennan FEATURES NEws TeAM Thomas Raethel, Claudia Herron, 28 | The Great Annual Critic Jamie Breen, Josie Cochrane, BYO Review Jack Montgomerie, Bella Macdonald Taking one for the team, Ines Shennan bravely volunteered for Critic’s annual culinary foray SECTION EDITORS to find Dunedin’s best BYO restaurant for the Rosie Howells, Charlotte Doyle, discerning student palate. Lucy Hunter, Kirsty Dunn, Baz Macdonald, Basti Menkes, Raquel Moss, Tristan Keillor 32 | Me and My Genome Genomics offers incredible new possibilities in CONTRIBUTORS 08 preventive medicine, and it is now possible to Jacobin, Guy McCallum, NEWS have one’s genome sequenced for under $100. Jessica Bromell, Dr. Nick, But how much do we really want to know about Lindsey Horne, Alex Wilson, 08 | DCC Shafts Students ourselves, and is this information safe? Lindsey Tamarah Scott, Jonny Mahon-Heap, Despite Withdrawing Poll Horne investigates M and G, Hannah Twigg, The Dunedin City Council has scrapped Campbell Ecklein plans to introduce a polling booth on NEWS campus during the upcoming local body elections. -

Helixtrolysis by Louis Armand

HELIXTROLYSIS CYBEROLOGY & THE JOYCEAN “TYRONDYNAMON MACHINE” LOUIS ARMAND Prague 2014 Litteraria Pragensia Books www.litterariapragensia.com Copyright © Louis Armand, 2014 Published 2014 by Univerzita Karlova v Praze Filozofická Fakulta Litteraria Pragensia Books Centre for Critical & Cultural Theory, DALC Náměstí Jana Palacha 2 116 38 Praha 1, Czech Republic All rights reserved. This book is copyright under international copyright conventions. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without prior written permission from the copyright holders. Requests to publish work from this book should be directed to the publishers. The research & publication of this book have been supported from the ‘Program rozvoje vědních oblastí na Univerzitě Karlově,’ no. 9: ‘Literature & Art in Intercultural Relationships,’ subproject: ‘Transformations of Cultural Histories of Anglophone Countries: Identities, Periods, Canons.’ Cataloguing in Publication Data HELIXTROLYSIS: Cyberology and the Joycean “Tyrondynamon Machine,” by Louis Armand.—1st ed. p. cm. ISBN 978-80-7308-539-1 1. Critical Theory. 2. James Joyce. 3. Literary Theory. I. Armand, Louis. II. Title Printed in the Czech Republic by PB Tisk Cover, typeset & design © lazarus i.m. Donald F. Theal & Alan R. Roughley Contents Joycean Machines LITERATE TECHNOLOGIES 5 ABSTRACTION 8 EXPERIMENTAL LOGIC 10 TECHNĒ 12 Experimental Machines ENTROPOLOGY 15 MAXWELL’S DEMON 21 MACHINIC PERIODICITY