Helixtrolysis by Louis Armand

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Entourage Effect at Finnegans Wake 1

The Entourage Effect At Finnegans Wake 1 The Entourage Effect At Finnegans Wake The Entourage Effect At Finnegans Wake. Steven James Pratt 2 The Entourage Effect At Finnegans Wake FORE WORDS Cannabis and Finnegans Wake are two of my favourite things, and I’ve been engaging with both for over twenty years. This paper pulls from, and pushes upon my experiences, and attempts to roll-it-all-up into a practical guide-cone. Not only a theoretical series of “what ifs,” but also a helpful introduction to the book and to the flower, “seedsmanchap” (FW, 221.) with luck enhancing the experience of reading and the positive effects of cannabis. If you’re already bored, scroll to the bottom and follow some of the links. Finnegans Wake (FW) for me, serves up the perfect antidote for those who do not read much these days. FW is the book for you, today. Get stuck in, light up, lighten up, there’s no right or wrong way to speak it aloud just try and make it new, explore your accents, keep it fresh. Use it as a doorstop, just go get a copy and let it grow on you. In the post-truth era of corporate-state controlled news’ media outlets, we might all use a lil’ linguistic and semantical earthquake, to shake loose the lies and dislodge the tantalizing deceits, and to rattle the vacuous gossip columns to pieces. Finnegans Wake, mixed with cannabis is my best bet, my offering, for a universal toolkit to help break on through to the other side with enough laughs and some shrieks of joy to prevent you crying yourself to sleep in depression at the state of the planet. -

True Sacrifice on Hegel's Presentation of Self-Consciousness

UDK: 130.3 FILOZOFIJA I DRUŠTVO XXVI (4), 2015. DOI: 10.2298/FID1504830K Original scientific article Received: 25.11.2105 — Accepted: 4.12.2105 Zdravko Kobe True Sacrifice On Hegel’s Presentation of Self-Consciousness Abstract The paper provides a modest reading of Hegel’s treatment of self- consciousness in his Phenomenology of Spirit and tries to present it as an integral part of the overall project of the experience of consciousness leading from understanding to reason. Its immediate objective is, it is argued, to think the independence and dependence, that is the pure and empirical I within the same unity of self-consciousness. This implies a double movement of finding a proper existence for the pure I and at the same time a breaking down of the empirical I’s attachment to particularity. It is argued that the Hegelian strug- gle for recognition intends to show how the access to reason demands the subject’s renunciation of its attachment to particularity, that is to sacrifice not only its bare life but every thing indeed, including its particular identity, 830 and yet, to go on living. Keywords: Hegel, Phenomenology of Spirit, self-consciousness, desire, recog- nition, master and servant, sacrifice, departicularisation, reason The chapter on self-consciousness in Hegel’s Phenomenology of Spirit gave rise to a flood of interpretations that made it one of the most widely commented pieces in the history of modern philosophy. Its success was partly due to the famous Paris lectures of Kojève who, combining Marx and Heidegger, presented it as a core matrix of Hegel’s entire thought. -

Of Finnegans Wake

University of Mississippi eGrove Electronic Theses and Dissertations Graduate School 2013 Pedagogy And Identity In "The Night Lessons" Of Finnegans Wake Zachary Paul Smola University of Mississippi Follow this and additional works at: https://egrove.olemiss.edu/etd Part of the Literature in English, British Isles Commons Recommended Citation Smola, Zachary Paul, "Pedagogy And Identity In "The Night Lessons" Of Finnegans Wake" (2013). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 541. https://egrove.olemiss.edu/etd/541 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at eGrove. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of eGrove. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ! PEDAGOGY AND IDENTITY IN “THE NIGHT LESSONS” OF FINNEGANS WAKE A Thesis Presented for the Master of Arts Degree in the Department of English The University of Mississippi ZACHARY P. SMOLA May 2013 ! ! Copyright © 2013 by Zachary P. Smola All rights reserved ! ABSTRACT This thesis explores chapter II.ii of James Joyce’s Finnegans Wake (1939)—commonly called “The Night Lessons”—and its peculiar use of the conventions of the textbook as a form. In the midst of the Wake’s abstraction, Joyce uses the textbook to undertake a rigorous exploration of epistemology and education. By looking at the specific expectations of and ambitions for textbooks in 19th century Irish national schools, this thesis aims to provide a more specific historical context for what textbooks might mean as they appear in Finnegans Wake. As instruments of cultural conditioning, Irish textbooks were fraught with tension arising from their investment in shaping religious and political identity. -

Roth Book Notes--Mcluhan.Pdf

Book Notes: Reading in the Time of Coronavirus By Jefferson Scholar-in-Residence Dr. Andrew Roth Mediated America Part Two: Who Was Marshall McLuhan & What Did He Say? McLuhan, Marshall. The Mechanical Bride: Folklore of Industrial Man. (New York: Vanguard Press, 1951). McLuhan, Marshall and Bruce R. Powers. The Global Village: Transformations in World Life and Media in the 21st Century. (New York: Oxford University Press, 1989). McLuhan, Marshall. The Gutenberg Galaxy: The Making of Typographic Man. (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1962). McLuhan, Marshall. Understanding Media: The Extensions of Man. (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1994. Originally Published 1964). The Mechanical Bride: The Gutenberg Galaxy Understanding Media: The Folklore of Industrial Man by Marshall McLuhan Extensions of Man by Marshall by Marshall McLuhan McLuhan and Lewis H. Lapham Last week in Book Notes, we discussed Norman Mailer’s discovery in Superman Comes to the Supermarket of mediated America, that trifurcated world in which Americans live simultaneously in three realms, in three realities. One is based, more or less, in the physical world of nouns and verbs, which is to say people, other creatures, and things (objects) that either act or are acted upon. The second is a world of mental images lodged between people’s ears; and, third, and most importantly, the mediasphere. The mediascape is where the two worlds meet, filtering back and forth between each other sometimes in harmony but frequently in a dissonant clanging and clashing of competing images, of competing cultures, of competing realities. Two quick asides: First, it needs to be immediately said that Americans are not the first ever and certainly not the only 21st century denizens of multiple realities, as any glimpse of Japanese anime, Chinese Donghua, or British Cosplay Girls Facebook page will attest, but Americans first gave it full bloom with the “Hollywoodization,” the “Disneyfication” of just about anything, for when Mae West murmured, “Come up and see me some time,” she said more than she could have ever imagined. -

The Being of Analogy Noah Roderick Noah Roderick the Being of Analogy

Noah Roderick The Being of Analogy Noah Roderick Noah Roderick The Being of Analogy The Being of Modern physics replaced the dualism of matter and form with a new distinction between matter and force. In this way form was marginalized, and with it the related notion of the object. Noah Roderick’s book is a refreshing effort to reverse the consequences of this now banal mainstream materialism. Ranging from physics through literature to linguistics, spanning philosophy from East to West, and weaving it all together in remarkably lucid prose, Roderick intro- duces a new concept of analogy that sheds unfamiliar light on such thinkers as Marx, Deleuze, Goodman, Sellars, and Foucault. More than a literary device, analogy teaches us something about being itself. OPEN HUMANITIES PRESS Cover design by Katherine Gillieson · Illustration by Tammy Lu The Being of Analogy New Metaphysics Series Editors: Graham Harman and Bruno Latour The world is due for a resurgence of original speculative metaphysics. The New Metaphys- ics series aims to provide a safe house for such thinking amidst the demoralizing caution and prudence of professional academic philosophy. We do not aim to bridge the analytic- continental divide, since we are equally impatient with nail-filing analytic critique and the continental reverence for dusty textual monuments. We favor instead the spirit of the intel- lectual gambler, and wish to discover and promote authors who meet this description. Like an emergent recording company, what we seek are traces of a new metaphysical ‘sound’ from any nation of the world. The editors are open to translations of neglected metaphysical classics, and will consider secondary works of especial force and daring. -

Works on Giambattista Vico in English from 1884 Through 2009

Works on Giambattista Vico in English from 1884 through 2009 COMPILED BY MOLLY BLA C K VERENE TABLE OF CON T EN T S PART I. Books A. Monographs . .84 B. Collected Volumes . 98 C. Dissertations and Theses . 111 D. Journals......................................116 PART II. Essays A. Articles, Chapters, et cetera . 120 B. Entries in Reference Works . 177 C. Reviews and Abstracts of Works in Other Languages ..180 PART III. Translations A. English Translations ............................186 B. Reviews of Translations in Other Languages.........192 PART IV. Citations...................................195 APPENDIX. Bibliographies . .302 83 84 NEW VICO STUDIE S 27 (2009) PART I. BOOKS A. Monographs Adams, Henry Packwood. The Life and Writings of Giambattista Vico. London: Allen and Unwin, 1935; reprinted New York: Russell and Russell, 1970. REV I EWS : Gianturco, Elio. Italica 13 (1936): 132. Jessop, T. E. Philosophy 11 (1936): 216–18. Albano, Maeve Edith. Vico and Providence. Emory Vico Studies no. 1. Series ed. D. P. Verene. New York: Peter Lang, 1986. REV I EWS : Daniel, Stephen H. The Eighteenth Century: A Current Bibliography, n.s. 12 (1986): 148–49. Munzel, G. F. New Vico Studies 5 (1987): 173–75. Simon, L. Canadian Philosophical Reviews 8 (1988): 335–37. Avis, Paul. The Foundations of Modern Historical Thought: From Machiavelli to Vico. Beckenham (London): Croom Helm, 1986. REV I EWS : Goldie, M. History 72 (1987): 84–85. Haddock, Bruce A. New Vico Studies 5 (1987): 185–86. Bedani, Gino L. C. Vico Revisited: Orthodoxy, Naturalism and Science in the ‘Scienza nuova.’ Oxford: Berg, 1989. REV I EWS : Costa, Gustavo. New Vico Studies 8 (1990): 90–92. -

What Cant Be Coded Can Be Decorded Reading Writing Performing Finnegans Wake

ORBIT - Online Repository of Birkbeck Institutional Theses Enabling Open Access to Birkbecks Research Degree output What cant be coded can be decorded Reading Writing Performing Finnegans Wake http://bbktheses.da.ulcc.ac.uk/198/ Version: Public Version Citation: Evans, Oliver Rory Thomas (2016) What cant be coded can be decorded Reading Writing Performing Finnegans Wake. PhD thesis, Birkbeck, University of London. c 2016 The Author(s) All material available through ORBIT is protected by intellectual property law, including copyright law. Any use made of the contents should comply with the relevant law. Deposit guide Contact: email “What can’t be coded can be decorded” Reading Writing Performing Finnegans Wake Oliver Rory Thomas Evans Phd Thesis School of Arts, Birkbeck College, University of London (2016) 2 3 This thesis examines the ways in which performances of James Joyce’s Finnegans Wake (1939) navigate the boundary between reading and writing. I consider the extent to which performances enact alternative readings of Finnegans Wake, challenging notions of competence and understanding; and by viewing performance as a form of writing I ask whether Joyce’s composition process can be remembered by its recomposition into new performances. These perspectives raise questions about authority and archivisation, and I argue that performances of Finnegans Wake challenge hierarchical and institutional forms of interpretation. By appropriating Joyce’s text through different methodologies of reading and writing I argue that these performances come into contact with a community of ghosts and traces which haunt its composition. In chapter one I argue that performance played an important role in the composition and early critical reception of Finnegans Wake and conduct an overview of various performances which challenge the notion of a ‘Joycean competence’ or encounter the text through radical recompositions of its material. -

Early Sources for Joyce and the New Physics: the “Wandering Rocks” Manuscript, Dora Marsden, and Magazine Culture

GENETIC JOYCE STUDIES – Issue 9 (Spring 2009) Early Sources for Joyce and the New Physics: the “Wandering Rocks” Manuscript, Dora Marsden, and Magazine Culture Jeff Drouin The bases of our physics seemed to have been put in permanently and for all time. But these bases dissolve! The hour accordingly has struck when our conceptions of physics must necessarily be overhauled. And not only these of physics. There must also ensue a reissuing of all the fundamental values. The entire question of knowledge, truth, and reality must come up for reassessment. Obviously, therefore, a new opportunity has been born for philosophy, for if there is a theory of knowledge which can support itself the effective time for its affirmation is now when all that dead weight of preconception, so overwhelming in Berkeley's time, is relieved by a transmuting sense of instability and self-mistrust appearing in those preconceptions themselves. — Dora Marsden, “Philosophy: The Science of Signs XV (continued)—Two Rival Formulas,” The Egoist (April 1918): 51. There is a substantial body of scholarship comparing James Joyce's later work with branches of contemporary physics such as the relativity theories, quantum mechanics, and wave-particle duality. Most of these studies focus on Finnegans Wake1, since it contains numerous references to Albert Einstein and also embodies the space and time debate of the mid-1920s between Joyce, Wyndham Lewis and Ezra Pound. There is also a fair amount of scholarship on Ulysses and physics2, which tends to compare the novel's metaphysics with those of Einstein's theories or to address the scientific content of the “Ithaca” episode. -

Rezension Von: Michael Groden: Ulysses in Progress: Princeton, 1977

James Joyce Quarterly University of Tulsa Tulsa, Oklahoma 74104 THOMAS F. STALEY Editor FRITZ SENN . European Editor CHARLOTTE STEWART Managing Editor ALAN M. COHN ... Bibliographer MARK DUNPHY, CURTIS COTTRELL, CORINNA DEL GRECO LOBNER Graduate Assistants ADVISORY EDITORS James R. Baker, San Diego State University, California; Bernard Benstock, University of Illinois; Heimet Bonheim, University of Cologne; Robert Boyle, S.J., Marquette University; Edmund Epstein, Queens College; Bernard Fleischmann, Montclair State College; Hans Walter Gabler, University of Munich; Arnold Goldman, University of Keele; Nathan Halper; Clive Hart, University of Essex; David Hayman, University of Wisconsin; Phillip Herring, University of Wisconsin; Fred Higginson, Kansas State University; Richard M. Kain, University of Louisville; Hugh Kenner, The Johns Hopkins University; Leo Knuth, University of Utrecht; A. Walton Litz, Princeton University; Vivian Mercier, University of California, Santa Barbara; Margot C. Norris, University of Michigan; Darcy O'Brien, University of Tulsa; Joseph Prescott, Wayne State University; Hugh Staples, University of Cincinnati; Weldon Thornton, University of North Carolina. Single Copy Price $3.00 (U.S.); $3.50 (foreign) Subscription Rates United States Elsexvhere 1 year 2 years 3 years 1 year 2 years 3 years Individuais: $10.00 $19.50 $29.00 $11.00 $21.50 $32.00 Institutions: 11.00 21.50 32.00 12.00 23.50 35.00 Send subscription inquiries and address changes to James Joyce Quarterly, University of Tulsa, Tulsa, OK 74104. Claims for back issues will be honored for three months only. All back issues except for the current volume may be ordered from Swets & Zeitlinger, Heereweg 347b, Lisse, The Netherlands, or P.O. -

Boston College Philosophy Department Spring 2009 Courses

Boston College Philosophy Department Spring 2009 Courses PL26403 LOGIC M W F 11 PURCELL PL29201 PHILOS OF COMMUNITY II T 4 30-6 15 MC MENAMIN PL29201 PHILOS OF COMMUNITY II T 4 30-6 15 FLANAGAN PL33901 HEIDEGGER PROJECT II T TH 1 30* OWENS PL40701 MEDIEVAL PHILOSOPHY T TH 10 30* SOLERE PL40801 19TH&20TH CEN PHILOSOPHY T TH 1 30* COBB-STEVENS PL44201 ROMANTICISM & IDEALISM T TH 1 30* RUMBLE PL45301 GANDHI,SATYAGRAHA&SOCIETY T TH 9* THAKER PL45601 HOLOCAUST:MORAL HISTORY T TH 3* BERNAUER PL47401 LAUGHTER,HUMOR,SATIRE M W F 1 O'BRIEN PL49701 PARMENIDES AND THE BUDDHA M W F 2 MARTIN PL50201 AMERICAN PRAGMATISM M W 3* WELLS PL50501 THE ARISTOTELIAN ETHICS M W F 1 MADIGAN PL51101 AFRICAN PHILOSOPHY M W 3* ONYANGO-ODUKE PL51201 PHILOSOPHY OF EXISTENCE T TH 3* KEARNEY PL52601 INTRO TO FEMINIST PHIL M W F 9 MC COY PL53201 PHIL RELIGION HUMAN SUBJ M W 3* BLANCHETTE PL53301 CAPSTONEPOETSPHLSPHRSMAPS TH 3-5 20 MCNELLIS PL54101 HEALTH SCIENCE:EAST/WEST T TH 12* THAKER PL54401 INTRO TO PHENOMENOLOGY T TH 10 30* KELLY PL58301 PHILOSOPHY OF BIOLOGY M W F 2 MCKAUGHAN PL61301 NATURAL LAW/NATURAL RIGHT F 10-11 50 ARAUJO PL69301 OEDIPUS AND PHILOSOPHY M W F 10 BLOECHL PL69801 HOSTING THE STRANGER W 5-6 50 KEARNEY For Graduate Students & Dept Permission Only DAVENPORT PL75701 KANT&LONERGAN ON ETHICS TH 4 30-6 50 BYRNE PL78801 ARISTOTLE'S METAPHYSICS TH 4 30-6 20 WIANS PL79101 ARISTOTLE/PLOTINUS/SOUL T 4 30-6 15 GURTLER PL79401 PHILOSOPHY/CHURCH FATHERS M W 3* SCHATKIN PL82701 ADVANCED MODERN PHIL W 2-3 50 SOLERE PL83201 PHIL&THEO IN AQUINAS M 6 30-8 15 BLANCHETTE PL83901 HEGEL W 4 30-6 50 SALLIS PL85601 SEM:HEIDEGGER II W 3-4 20 OWENS PL90101 HUSSERL'S LATER WORKS T 4 30-6 15 COBB-STEVENS PL99001 TEACHING SEMINAR F 4 30-6 COBB-STEVENS PL 160 02 Challenge of Justice Matthew Mullane M W 3* T TH 9* Level 1 – Undergraduate Elective Description: This course introduces the student to the principal understandings of justice that have developed in the Western philosophical and theological traditions. -

The New Socio-Cultural Paradigms and the Role of Jesuit Universities

The New Socio-Cultural Paradigms and the Role of Jesuit Universities Card. GIANFRANCO RAVASI A PREMISE The very word “university” philologically implies the task of embracing the “universe” of knowledge we are immersed in, and the quest to lead a great variety of knowledges into a “unity.” So universities, with their various faculties, departments, institutions, laboratories and so on, must always be careful to look both to the great heritage of the past and to the present time with its cultural paradigm shifts. We wish, here, to raise two different issues from a methodological point of view. The first is particularly significant within the horizon of the Jesuit universities. In a speech to the Roman Curia on December 22, 2016, Pope Francis proposed an “ancient saying that illustrates the dynamics of the Ignatian Spiritual Exercises, that is: deformata reformare, reformata conformare, conformata confirmare, confirmata transformare.” It is clear that there is a need for evolution and continuity in this process, for a dialogue with the past and an encounter with the present, for dialectics but also continuity, for changeable complexity and a basic single project. This is something raised by another voice – that of a personality quite different from Pope Francis – who based himself on the contemporary situation. Just before he died in 2011, Steve Jobs, the acclaimed founder of “Apple,” made a declaration that can be taken as his ideal testament: “Technology alone is not 2 enough. It’s technology married with liberal arts, married with the humanities, that yields us the results that make our hearts sing.” Practically, this was the symbolic synthesis of one of his earlier speeches, given June 12, 2005, at the university of Harvard. -

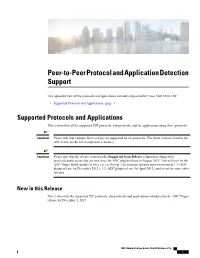

Peer-To-Peer Protocol and Application Detection Support

Peer-to-Peer Protocol and Application Detection Support This appendix lists all the protocols and applications currently supported by Cisco ASR 5500 ADC. • Supported Protocols and Applications, page 1 Supported Protocols and Applications This section lists all the supported P2P protocols, sub-protocols, and the applications using these protocols. Important Please note that various client versions are supported for the protocols. The client versions listed in the table below are the latest supported version(s). Important Please note that the release version in the Supported from Release column has changed for protocols/applications that are new since the ADC plugin release in August 2015. This will now be the ADC Plugin Build number in the x.xxx.xxx format. The previous releases were versioned as 1.1 (ADC plugin release for December 2012 ), 1.2 (ADC plugin release for April 2013), and so on for consecutive releases. New in this Release This section lists the supported P2P protocols, sub-protocols and applications introduced in the ADC Plugin release for December 1, 2017. ADC Administration Guide, StarOS Release 21.6 1 Peer-to-Peer Protocol and Application Detection Support New in this Release Protocol / Client Client Version Group Classification Supported from Application Release 6play 6play (Android) 4.4.1 Streaming Streaming-video ADC Plugin 2.19.895 Unclassified 6play (iOS) 4.4.1 6play — (Windows) BFM TV BFM TV 3.0.9 Streaming Streaming-video ADC Plugin 2.19.895 (Android) Unclassified BFM TV (iOS) 5.0.7 BFM — TV(Windows) Clash Royale