“Ways of Staying”

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hlophe Tribunal on Brink of Collapse?

Legalbrief | your legal news hub Thursday 30 September 2021 Hlophe tribunal on brink of collapse? SA's first tribunal with the power to recommend the removal of a judge from office appears to be on the brink of collapse, notes Legalbrief. Five years after Constitutional Court judges first lodged a misconduct complaint against Western Cape Judge President John Hlophe, the JSC's Judicial Conduct Tribunal is to decide tomorrow whether it considers itself 'legitimate'. A City Press report noted yesterday's adjournment of the hearing comes after lawyers representing the two justices of the Constitutional Court at the centre of the matter argued that they have a 'right not to testify before an illegitimate structure'. Selby Mbenenge SC, who is representing Justices Chris Jafta and Bess Nkabinde, the two Hlophe allegedly tried to influence in favour of President Jacob Zuma, said that the tribunal should not even be postponed; it should just 'pack up and go'. Mbenenge has argued on behalf of the two justices that the rules which apply to the proceedings are those which were in force before the Judicial Service Commission (JSC) Act was amended in 2010. The JSC Act required that the rules be published in the Government Gazette by the Minister of Justice, which was never done. For this reason, argues Mbenenge, the tribunal - appointed in terms of the amended legislation - is 'not a properly appointed structure'. According to the report, Mbenenge has argued that if he is wrong, and the new rules apply, they will then rely on an argument advanced by Hlophe's legal team on Monday that the JSC has since last year dealt with this matter under the new Act. -

Judicial Independce in South Africa: a Constitutional Perspective

1 JUDICIAL INDEPENDCE IN SOUTH AFRICA: A CONSTITUTIONAL PERSPECTIVE by Lunga Khanya Siyo (209509051) Submitted in part fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Laws in Constitutional Litigation (LLM) in the School of Law at the University of KwaZulu Natal Supervisor: Professor John C Mubangizi December 2012 2 DECLARATION I, Lunga Khanya Siyo, registration number 209509051, hereby declare that the dissertation entitled “Judicial Independence in South Africa: A Constitutional Perspective” is the result of my own unaided research and has not been previously submitted in part or in full for any other degree or to any other University. Signature: ………………………… Date: ……………………………… 3 DEDICATION This dissertation is dedicated to my parents, Milile Mpambaniso and Ncedeka Siyo. 4 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I am indebted to a number of people who have directly and indirectly assisted me in writing this dissertation. I‟d like to thank my parents, who taught me that there is no substitution for hard work and dedication. I thank them for their wisdom, guidance and support. I am nothing without them. This dissertation would not have been possible without the supervision of Professor John C Mubangizi. I am indebted to him for affording me the privilege of working with him during the course of this year. I‟d like to thank him for his advice and invaluable lessons. Most importantly, I am indebted to him for his incisive comments and contributions. My sincere gratitude goes to Ms Marelie Martiz from the School of Law. Although she did not have any involvement in writing this dissertation, she has assisted me in many other academic endeavours. -

Gender, Power and Iron Metallurgy in Archives of African Societies from the Phongolo-Mzimkhulu Region

Gender, power and iron metallurgy in archives of African societies from the Phongolo-Mzimkhulu region Steven Kotze A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Humanities, University of Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, in fulfilment of the requirements of Master of Arts. Durban, 2018 Declaration I declare that this thesis is my own, unaided work unless otherwise acknowledged. It is being submitted for the Degree of Master of Arts at the University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg. It has not been submitted before for any degree or examination at any other university. Steven Kotze 15 July 2018 i Abstract This dissertation examines the social, cultural and economic significance of locally forged field-hoes, known as amageja in Zulu. A key question I have engaged in this study is whether gender-based divisions of labour in nineteenth-century African communities of this region, which largely consigned agricultural work to women, also affect attitudes towards the tools they used. I argue that examples of field-hoes held in eight museum collections form an important but neglected archive of “hoeculture”, the form of subsistence crop cultivation based on the use of manual implements, within the Phongolo-Mzimkhulu geographic region that roughly approximates to the modern territory of KwaZulu-Natal. In response to observations made by Maggs (1991), namely that a disparity exists in the numbers of field- hoes collected by museums in comparison with weapons, I conducted research to establish the present numbers of amageja in these museums, relative to spears in the respective collections. The dissertation assesses the historical context that these metallurgical artefacts were produced in prior to the twentieth-century and documents views on iron production, spears and hoes or agriculture recorded in oral testimony from African sources, as well as Zulu-language idioms that make reference to hoes. -

Jacob Zuma: the Man of the Moment Or the Man for the Moment? Alex Michael & James Montagu

Research & Assessment Branch African Series Jacob Zuma: The Man of the Moment or the Man for the Moment? Alex Michael & James Montagu 09/08 Jacob Zuma: The Man of the Moment or the Man for the Moment? Alex Michael & James Montagu Key Findings • Zuma is a pragmatist, forging alliances based on necessity rather than ideology. His enlarged but inclusive cabinet, rewards key allies with significant positions, giving minor roles to the leftist SACP and COSATU. • Long-term ANC allies now hold key Justice, Police and State Security ministerial positions, reducing the likelihood of legal charges against him resurfacing. • The blurring of party and state to the detriment of public institutions, which began under Mbeki, looks set to continue under Zuma. • Zuma realises that South Africa relies too heavily on foreign investment, but no real change in economic policy could well alienate much of his populist support base and be decisive in the longer term. 09/08 Jacob Zuma: The Man of the Moment or the Man for the Moment? Alex Michael & James Montagu INTRODUCTION Jacob Zuma, the new President of the Republic of South Africa and the African National Congress (ANC), is a man who divides opinion. He has been described by different groups as the next Mandela and the next Mugabe. He is a former goatherd from what is now called KwaZulu-Natal (KZN) with no formal education and a long career in the ANC, which included a 10 year spell at Robben Island and 14 years of exile in Mozambique, Swaziland and Zambia. Like most ANC leaders, his record is not a clean one and his role in identifying and eliminating government spies within the ranks of the ANC is well documented. -

The Power of Heritage to the People

How history Make the ARTS your BUSINESS becomes heritage Milestones in the national heritage programme The power of heritage to the people New poetry by Keorapetse Kgositsile, Interview with Sonwabile Mancotywa Barbara Schreiner and Frank Meintjies The Work of Art in a Changing Light: focus on Pitika Ntuli Exclusive book excerpt from Robert Sobukwe, in a class of his own ARTivist Magazine by Thami ka Plaatjie Issue 1 Vol. 1 2013 ISSN 2307-6577 01 heritage edition 9 772307 657003 Vusithemba Ndima He lectured at UNISA and joined DACST in 1997. He soon rose to Chief Director of Heritage. He was appointed DDG of Heritage and Archives in 2013 at DAC (Department of editorial Arts and Culture). Adv. Sonwabile Mancotywa He studied Law at the University of Transkei elcome to the Artivist. An artivist according to and was a student activist, became the Wikipedia is a portmanteau word combining youngest MEC in Arts and Culture. He was “art” and “activist”. appointed the first CEO of the National W Heritage Council. In It’s Bigger Than Hip Hop by M.K. Asante. Jr Asante writes that the artivist “merges commitment to freedom and Thami Ka Plaatjie justice with the pen, the lens, the brush, the voice, the body He is a political activist and leader, an and the imagination. The artivist knows that to make an academic, a historian and a writer. He is a observation is to have an obligation.” former history lecturer and registrar at Vista University. He was deputy chairperson of the SABC Board. He heads the Pan African In the South African context this also means that we cannot Foundation. -

Metaphor and Metanoia: Linguistic Transfer and Cognitive Transformation in British and Irish Modernism

Western University Scholarship@Western Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository 8-20-2013 12:00 AM Metaphor and Metanoia: Linguistic Transfer and Cognitive Transformation in British and Irish Modernism Andrew C. Wenaus The University of Western Ontario Supervisor Dr. Jonathan Boulter The University of Western Ontario Graduate Program in English A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree in Doctor of Philosophy © Andrew C. Wenaus 2013 Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd Part of the Continental Philosophy Commons, Literature in English, British Isles Commons, Modern Languages Commons, Modern Literature Commons, Other Arts and Humanities Commons, and the Philosophy of Mind Commons Recommended Citation Wenaus, Andrew C., "Metaphor and Metanoia: Linguistic Transfer and Cognitive Transformation in British and Irish Modernism" (2013). Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository. 1512. https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd/1512 This Dissertation/Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarship@Western. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository by an authorized administrator of Scholarship@Western. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Metaphor and Metanoia: Linguistic Transfer and Cognitive Transformation in British and Irish Modernism (Thesis Format: Monograph) by Andrew C. Wenaus Graduate Program in English A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy The School of Graduate and Postdoctoral Studies The University of Western Ontario London, Ontario, Canada © Andrew C. Wenaus 2013 ABSTRACT This dissertation contributes to the critical expansions now occurring in what Douglas Mao and Rebecca L. -

Fundamentalist Journal, Volume 2, Number 7

Liberty University DigitalCommons@Liberty University 1983 The undF amentalist Journal 7-1983 Fundamentalist Journal, Volume 2, Number 7 Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.liberty.edu/fun_83 Recommended Citation "Fundamentalist Journal, Volume 2, Number 7" (1983). 1983. Paper 1. http://digitalcommons.liberty.edu/fun_83/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the The undF amentalist Journal at DigitalCommons@Liberty University. It has been accepted for inclusion in 1983 by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@Liberty University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. TUNDAI"IENTALI.ET One Dollqr & Ninety-Five Cents JOUPNAL Jtrly/August 1983 OneNation underGod on the Rebound The Churchand Her Rights The Christian Churchunder Communism America WakeUp! I .r'-, v |<(,*,, ! {, ()L/ ( I {! t1 v *'e ';;il l-,rl llL. (; c:h:r{r "rj Fr It U, j/ e/ +- -<-r-o z,o 3,;S L <-l Fj (^l o3 i" t' f.l cm ::r !^-.,.. a^ uci r! tJ , -o aq; -a ,i >! iJ.l vm a*j Nt- 5T T Have you ever wondered why Christians are usually portrayed unsympatheticallyon TV and in movies? . Why our childrenare learning anti- Christiarrmoral valuesin public schools? . Why so few Christianbooks.rre in your localbookstore and library-even when they are bestsellers? V,lhy? Bacnusethcrc's {t ttcTLtlt)ltltc of cettsorshilt sTLteepifigArtrcrica. No, it's not the obvious kind that actuallybr-rrns books. It's somethirrg much more subtle-and more effective. The real censorstodav are hard-coresecu- laristswhtl hold the p.,siti.,nsof influence in education,the media, and public life. -

Reforming the Supreme Court of Canada

SPECIAL SERIES ON THE FEDERAL DIMENSIONS OF REFORMING THE SUPREME COURT OF CANADA Constitutional Court Appointment: The South African Process Yonatan T. Fessha Law Faculty, University of the Western Cape Institute of Intergovernmental Relations School of Policy Studies, Queen’s University SC Working Paper 2010 - 06 Fessha, Y.T. Constitutional Court Appointment: The South African Process…. Page 1 Introduction An important part of the constitutional democracy project that characterizes post-apartheid South Africa is the establishment of a constitutional court. The strong constitutional culture entrenched in the new South Africa is to a large extent attributable to the establishment, work and stature of the Constitutional Court. The aim of this paper is to provide a brief overview of the appointment process to the Constitutional Court. It also touches on the most relevant issues pertaining to the appointment of judges in South Africa, which is not only applicable to the Constitutional Court but extends to all other courts in the country. As a point of departure, the paper introduces the Constitutional Court. It then proceeds to discuss the Judicial Service Commission, the body responsible for the appointment and dismissal of judges. The appointment process for judges is briefly discussed after which the role of provincial representation in the appointment of judges is evaluated. Finally, the issue of racial and gender transformation of the judiciary is given brief attention. The Constitutional Court The Constitutional Court (CC) exercises jurisdiction only over constitutional matters and issues connected with decisions on constitutional matters.1 Declared by the Constitution as the highest court on constitutional matters,2 the court consists of the Chief justice, the Deputy Chief Justice and nine other judges. -

One Hundred Years of the Kwazulu-Natal Bench by LB Broster SC, a Coutsoudis and AJ Boulle, Kwazulu-Natal Bar

SA JUDICIARY100 YEARS OLD Juta, Kotzé and rule from 1949-1959), and Munnik CJ (from 1981-1992). Hlophe Menzies who were CJ, the first black JP of the division, is perhaps the best-known of either judges of the the current group of Judges President in the country. Amongst court or members of other things, he was responsible for the controversial decision in the families of judges of dispute between the Pharmaceutical Society of South Africa, New the court. Clicks South Africa (Pty) Ltd and the Minister of Health (New Clicks Perhaps the most South Africa (Pty) Ltd v Tshabalala-Msimang and Another NNO; well-known advocate Pharmaceutical Society of South Africa and Others v Tshabalala- ever to practise in Msimang and Another NNO 2005 (2) SA 530 (C)). the Cape was Harry The CPD also made important contributions to the development Snitcher QC, who also of the new constitutional law in cases such as the Grootboom deci- acted for appellants sion that enforced the right to housing (Government of the Republic Judge President John Hlophe, in the Harris decision, and Cape High Court of South Africa and Others v Grootboom and Others 2001 (1) SA 46 many another similar cause (CC)) and the Metrorail decision which enforced the right to life (Rail celebre. Commuters Action Group and Others v Transnet Ltd t/a Metrorail Of the Judges President of the court, several stand out purely and Others 2005 (2) SA 359 (CC)). because of the long duration of their tenure. These were Van Zyl CJ In this way the division has contributed to a process of constitu- (who took the court through the difficult years of the aftermath of tional development - from Slave Lodge to beacon of Good Hope. -

Bulletin 9 of 2018 MVDM

Bulletin 6 of 2013 Period: 1 February 2013 to 8 February 2013 Bulletin` 9 of 2018 Period: 02 March 2018 – 09 March 2018 IMPORTANT NEWS SUBDIVISION OF AGRICULTURAL LAND ACT 70 OF 1970 Certain properties have been excluded from the provisions of the Act iro the following municipalities: • Franshoek, Klapmuts, Lamotte, Lyndoch, Pniel, Languedoc, Kylemore, Raithby, Wemmershoek and Stellenbosch, Stellenbosch Local Municipality, Western Cape; • Tlokwe Local Municipality, North West; • City of Cape Town Metro Municipality, Western Cape; • Abbotsdale, Mooreesburg, Ongegund, Riebeek-Kasteel and Yzerfontein, Swartland Local Municipality, Western Cape; • KwaDukuza Municipality, KwaZulu-Natal; • Mandeni, Umswathi Municipality, KwaZulu-Natal; • Richmond, Impendle Municipality, KwaZulu-Natal; • Umgeni Local Municipality, KwaZulu-Natal, Witbank, Emalahleni Local Municipality, Mpumalanga, Mpofana Local Municipality, KwaZulu-Natal and Mkhambathini Local Municipality, KwaZulu-Natal; and • City of Matlosana Local Municipality, North West and Makhado Local Municipality, Limpopo Source: Government Gazette 41473, 2 March 2018 IMPORTANT NOTICE FOR INSOLVENCY PRACTITIONERS The Insolvency Steering Committee of the Master’s Office issued a notice that as from the 01 April 2018 the Masters Offices will no longer accept copies, emails or faxes of requisitions lodged. All Requisitions lodged must be Original. The section 9(3) security will also be increased to R30 000-00 as from the 01 April 2018. Source: The SARIPA Education, Training and Development Committee MORE AMENDMENTS TO POLICY HOLDER PROTECTION RULES Draft amendments to the long and short-term insurance policy holder protection rules released for comment include conduct of business requirements for micro-insurance products. According to an accompanying statement, once in force the amendments will also align each set of rules with the 2017 Insurance Act; and provide for certain conduct-of- business-related requirements under the Long and Short-term Insurance Acts pending their repeal. -

The Sichuan Avant-Garde, 1982-1992

China’s Second World of Poetry: The Sichuan Avant-Garde, 1982-1992 by Michael Martin Day Digital Archive for Chinese Studies (DACHS) The Sinological Library, Leiden University 2005 2 Table of Contents Acknowledgements ............................................................................................................4 Preface …………………..………………………………………………………………..7 Chapter 1: Avant-Garde Poetry Nationwide – A Brief Overview ……………..……18 Chapter 2: Zhou Lunyou: Underground Poetry during the 1970s ………………… 35 Chapter 3: The Born-Again Forest : An Early Publication …………….…………….46 Chapter 4: Macho Men or Poets Errant? ……………………………………………..79 Poetry on University Campuses………………………………………….79 A Third Generation………………………………………………………82 Hu Dong, Wan Xia, and Macho Men……………………………………88 Li Yawei………………………………………………………………….99 Ma Song………………………………………………………………...103 Finishing with University………………………………………………107 Chapter 5: A Confluence of Interests: The Institution of the Anti-Institutional ….114 Setting the Scene………………………………………………………..114 The Establishment of the Sichuan Young Poets Association…………..123 The First Product of the Association: Modernists Federation………….130 Chapter 6: The Poetry of Modernists Federation ……………………………………136 Chapter 7: Make It New and Chinese Contemporary Experimental Poetry ….…..…169 Growing Ties and a Setback……………………………………………170 Day By Day Make It New and the Makings of an Unofficial Avant-Garde Polemic…………....180 Experimental Poetry : A Final Joint Action…………………………….195 Chapter 8: Moving into the Public Eye: A Grand Exhibition -

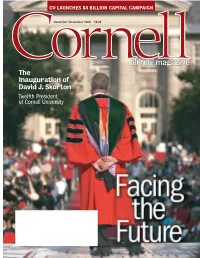

Alumni Magazine the Inauguration of David J

c1,c2,p1,c3,c4CAMND06 10/19/06 2:22 PM Page c1 CU LAUNCHES $4 BILLION CAPITAL CAMPAIGN November/December 2006 $6.00 alumni magazine The Inauguration of David J. Skorton Twelfth President of Cornell University c1,c2,p1,c3,c4CAMND06 10/19/06 4:00 PM Page c2 c1,c2,p1,c3,c4CAMND06 10/19/06 4:00 PM Page 1 002-003CAMND06toc 10/16/06 3:45 PM Page 2 Contents NOVEMBER / DECEMBER 2006 VOLUME 109 NUMBER 3 4 Letter From Ithaca alumni magazine French toast Features 6 Correspondence Natural selection 10 From the Hill The dawn of the campaign. Plus: Milstein Hall 3.0, meeting the Class of 2010, the ranking file, the Creeper pleads, and a new divestment movement. 16 Sports A rink renewed 18 Authors The full Marcham 35 Finger Lakes Marketplace 52 44 Wines of the Finger Lakes 46 In Our Own Words 2005 Lucas Cabernet Franc CAROL KAMMEN “Limited Reserve” To Cornell historian Carol Kammen, 62 Classifieds & Cornellians the unheard voices in the University’s in Business story belong to the students them- selves. So the senior lecturer dug into 65 Alma Matters the vaults of the Kroch Library and unearthed a trove of diaries, scrap- books, letters, and journals written by 68 Class Notes undergraduates from the founding to 109 the present.Their thoughts—now 46 assembled into a book, First-Person Alumni Deaths Cornell—reveal how the anxieties, 112 distractions, and preoccupations of students on the Hill have (and haven’t) changed since 1868.We offer some excerpts. Cornelliana Authority figures 52 Rhapsody in Red JIM ROBERTS ’71 112 The inauguration of David Skorton