Willem Pijper: an Aper.;Ul

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Piet Wackie Eysten Jubileumboek Van De Stichting Voor Kamermuziek

Jubileumboek van de stichting voor kamermuziek Piet Wackie eysten ‘String quartets trudge onstage hundreds of times a year and play music of the gods for a passionate and intensely involved audience. Not much to write about…’ Arnold Steinhardt, Indivisible by Four Inhoudsopgave 1. Een ‘voorloopige commissie’ 5 2. De Vereeniging voor Kamermuziek te ’s-Gravenhage 13 3. De eerste seizoenen 19 4. Koninklijke belangstelling 25 5. Programmering 29 6. Het 12½-jarig jubileum 35 7. Een nieuwe voorzitter 39 8. Het 25-jarig jubileum 45 9. Oorlogsjaren 51 10. Na de oorlog 57 11. De vijftiger jaren 63 12. Blijvend hoog niveau 67 13. De kosten 73 14. Ledenwerving 79 15. De ‘Vereeniging’ wordt een stichting 83 16. Bestuurswisselingen en stijgende prijzen 87 17. Donkere wolken 93 18. Een website tot slot 101 Inhoudsopgave / 3 Dr. D.F. Scheurleer Daniël François Scheurleer werd op 13 november 1855 geboren in Den Haag, waar zijn vader firmant was van het sinds 1804 in Den Haag gevestigde bankiershuis Scheurleer & Zoonen. De jonge Daniël trad bij zijn vaders firma in dienst, nadat hij in Dresden aan het ‘Handelslehranstalt’ een opleiding had gevolgd en bij de Dresdner Bank een stage had doorlopen. Na het overlijden van zijn vader in 1882 werd hij, nog slechts 26 jaar oud, directeur van het familiebedrijf. De firma hield zich vooral bezig met vermogensbeheer van welgestelde Hagenaars uit de hogere kringen. De schrijver Louis Couperus bankierde zijn leven lang bij Scheurleer & Zoonen. Couperus en zijn vrouw verkeerden op vriendschappelijke voet met de heer en mevrouw Scheurleer. In zijn testament bepaalde Couperus dat het vermogensbeheer van de stichting die hij met dat testament in het leven riep, zou worden gevoerd door ‘de tegenwoordige en toekomstige individueele leden van de firma Scheurleer & Zoonen’. -

6 Program Notes

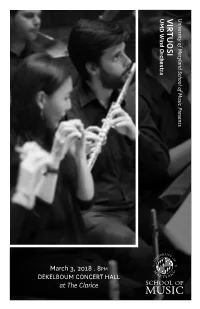

UMD Wind OrchestraUMD VIRTUOSI University Maryland of School Music of Presents March 3, 2018 . 8PM DEKELBOUM CONCERT HALL at The Clarice University of Maryland School of Music presents VIRTUOSI University of Maryland Wind Orchestra PROGRAM Michael Votta Jr., music director James Stern, violin Audrey Andrist, piano Kammerkonzert .........................................................................................................................Alban Berg I. Thema scherzoso con variazioni II. Adagio III. Rondo ritmico con introduzione James Stern, violin Audrey Andrist, piano INTERMISSION Serenade for Brass, Harp,Piano, ........................................................Willem van Otterloo Celesta, and Percussion I. Marsch II. Nocturne III. Scherzo IV. Hymne Danse Funambulesque .....................................................................................................Jules Strens I wander the world in a ..................................................................... Christopher Theofanidis dream of my own making 2 MICHAEL VOTTA, JR. has been hailed by critics as “a conductor with ABOUT THE ARTISTS the drive and ability to fully relay artistic thoughts” and praised for his “interpretations of definition, precision and most importantly, unmitigated joy.” Ensembles under his direction have received critical acclaim in the United States, Europe and Asia for their “exceptional spirit, verve and precision,” their “sterling examples of innovative programming” and “the kind of artistry that is often thought to be the exclusive -

Herinneringen Aan Eduard Van Beinum Nam Ook Hij Soms Zijn Toevlucht Tot Een Wijziging in De Instrumencacie of in De Dynamiek

28/ I t ï. 13 , I I 4 1 ,.' t, j t I JAARGANG: 1993 MAAND: DECEMBER NO:28 DIT BLAD IS EEN UITGAVE VAN DE: WILLEM MENG~LBERG VERENIGING opgericht 13 Februari 1987. SECRETARIAAT: DR. A. COSTER, ZIE ADRES / HIE~ONDER REDACTIE: DR. A. COSTER, AB VAN KAPEL, IRISLAAN 287, HOFBROUCKERLAAN 66, 2343 CN OEGSTGEEST. 2343 HZ OEGSTGEEST. TELEFOON: 071-175395. TELEFOON: 071-172562. SAMENSTELLING EN DISTRIBUTIE: JOHAN KREDIET, RIJKSSTRAATWEG 71, 1115 AJ DUIVENDRECHT. TELEFOON: 020-6991607 BESTUUR: v . VOORZITTER: OTTO HAMBURG VICE-VOORZITTER: PROF. DR. W.A.M. VAN DER KWAST SECRETARIS: DR. A. COSTER PENNINGMEESTER: DR. A. COSTER LEDEN: AB VAN KAPEL JOHAN KREDIET ... JURIDISCH ADVISEUR: MR. E.E.N. KRANS INHOUD VAN . DIT NUMMER: 1 van de redactie 3 MAHLERFEEST 1995 7 MUZIEK IN DE SCHADUW VAN HET DERDE RIJK 14 WILLEM KES 18 PIER RE MONTEUX 25 EDUARD VAN BEINUM 29 DISCOGRAFIE 31 KERSTMATINEES 40 CATHARINA VAN RENNES EN HAAR TIJDGENOTEN 41 EEN MUZIEKKRANSJE 43 MENGELBERG EN ZIJN TIJD 1886-1890 DE STATUTEN VAN ONZE VERENIGING -1- VAN DE REDACTIE De laatste tijd was er een grote belangstelling voor Mengel berg te constateren in de pers: le naar aanleiding van de plannen van het Concertgebouw om in 1995 een Mahle~-feest te organiseren, ongeveer naar model van het Mahler feest 75 jaar geleden in 1920 bij Mengelbergs 25- jarig jubileum; 2e naar aanleiding van de publicatie van het proefschrift van P,~uline Micheels: 'Muziek in de schaduw van het Derde rijk; De Nederlandse symfonie-orkesten 1933-1945' . Enkele artikelen uit de dagbladpers over deze onderwerpen zijn in dit nummer opgenomen. -

Download Artikel

UIT HET ARCHIEF Begin 20e eeuw was Bernard Zweers, samen met Johan Wagenaar en Alphons Diepenbrock, een van de leidende componisten binnen het Nederlandse muziekleven. Hij werd onsterfelijk met zijn derde symfonie Aan mijn Vaderland. Volgens musico- loog Eduard Reeser was deze symfonie Zweers’ geloofsbelijdenis. Maar wie was hij en wat waren zijn compositorische idealen? AUTEUR MARGARET KRILL NationaalBERNARD ZWEERS (1854-1924) componist Bernard Zweers kwam uit een Amsterdamsch Conservatorium. Ook gaf hij jaarlijks analyse- COLLECTIE NMI muzikaal gezin. Zijn vader cursussen in het Concertgebouw, waarin hij veel eigentijdse zong, was amateurcomponist, muziek behandelde. had een muziekhandel en ver- kocht piano’s. Bernard, zijn HOLLANDSCHE KUNST oudste zoon, kwam al snel in Als compositieleraar kreeg Zweers veel leerlingen die als de zaak waar hij ook piano’s componist naam zouden maken, zoals Sem Dresden, Daniel ging stemmen. Hij kreeg daar- Ruyneman, Anthon van der Horst en Willem Landré. Toch naast muzieklessen en op maakte hij zelf als componist niet echt ‘school’, daarvoor was veertienjarige leeftijd kocht hij waarschijnlijk veel te tolerant tegen zijn studenten. Wel hij theorieboeken omdat hij probeerde hij zijn leerlingen het belang van het bestaansrecht BERNARD ZWEERS graag wilde leren compone- van een Nederlandse toonkunst bij te brengen. Zweers zette ren. In de winkel van zijn zich namelijk nadrukkelijk af tegen de dominante muzikale vader leerde Bernard veel musici kennen zoals Johannes invloed uit Duitsland. Hij gaf een tegengeluid door zijn eigen Verhulst en ook een zekere J.W. Wilson waarmee hij veel liederen bijna uitsluitend op Nederlandse teksten te compo- quatre-mains ging spelen. Wilson nam hem in 1881 mee neren. -

Cr Lid \PAARGANG: 1998 MMN~: September NO : 47 1,1

- -., Iv1rwr-rrr--'IIIIF~N~LLIbBR~ 1_11 BM ~IcJN . cr lID \PAARGANG: 1998 MMN~: september NO : 47 1,1_ Dit blad is een uitgave van de WILLEfv1 MENGELBERG VERENIGING Opgericht 13 februari 1'987 SECRETARIAAT: Irislaan 287 2343 CN Oegstgeest 071-5175395 giro 155802 REDACTIE: Dr. A. Coster A. van Kapel .J. Krediet Irislaan·287 Hofbrouckerlaan 66 Rijksstraatweg 71 2343 CN Oegstgeest 2343 HZ Oegstgeest 111 5 AJ Duivendrecht 071-5175395 071-5172562 020-6991607 BESTUUR: Voorzitter: Prof. Dr. W.A.M. van der Kwast Vice-voorzitter Dr. W. van Welsenes Secr./penningm. Dr. A. Coster leden: A. van Kapel .L Krediet Juridisch adviseur Mr. E.E.N. Krans ***************.*.*************************************************************************** INHOUD VAN DIT NUMMER: OJ VAN DE REDACTIE 02-05 BERGEN 1898-1998 VOERMANS, ER IK 06 CONCERTGEBOUW 1898-1928 WAGENAAR, JOHAN 07-09 DE INVLOED SFEER VAN HET CONCERTGEB. DRESDEN, SEM 10-11 DE NEDERLANDSE COMPONISTEN DOPPER, CORN. 12 40-JAAR CULTURELE ARBEID ANROOY., PETER V 13-15 HET AMSTERDAMSCHE MUZIEKLEVEN IN 1928 PIJPER, WILLEM 16 DASS, DAS C.O. STETS BLüHEN MöGE STRAUSS, RICHARD 17 DAS C.O. IST DAS FUNDAMENT MAHLER, GUSTAV 18 VIVAT, CRESCAT, FLOREAT WALTHER, BRUNO 1 9 GRATULATIONS ELGAR, EDWARD 21 IL N'EXCISTE EN EUROPE CASELLO, ALFREDO 22-23 MUSIC IST DIE HöCHSTE AUSDRUCKKUNST NIELSEN, CARL 24-26 PROGRAMMA'S 40-JARIG JUBILEUM 27 1938 JUBILEUM H.M. KON. WILHELMINA 28-33 CARTE BLANCHE VOOR BERNARD HAITINK VOERMANS, ERIK 34-35 IK BEN NIET ZO BEROEMD ALS EEN POPSTER KOELEWIJN, JANN. 36-38 HENRIëTTE BOSMANS CHAPIRO, FAN IA 39-40 FRED. J. ROESKE ARNOLDUSSEN,P. -

Cele Mai Cunoscute Orchestre Simfonice Din Lume

Scris de cristina.mihalascu pe 24 octombrie 2010, 16:57 Cele mai cunoscute orchestre simfonice din lume - Sinteza unt ansambluri muzicale care au supravietuit regimurilor politice si razboaielor, care s-au adaptat schimbarilor vremii, dar care au ramas fidele stilului clasic de muzica. Cu moneda proprie sau nu, cu dirijori faimosi, cu propriile case de discuri si cu premii internationale, orchestrele simfonice ale lumii sunt calatorii muzicale catre desavarsirea sunetului. usa_chicago_orchestrahall_3.jpg Pe langa muzica, ele spun istoria. In fata modei, ele impun statornicia. Despre istoria institutiilor care au pastrat vie muzica culta, puteti citi in frazele care urmeaza. Trei publicatii de prestigiu dedicate industriei muzicale clasice, printre care monteverdi.tv, gramophone.co.uk si musolife.com, considera ca urmatoarele cinci orchestre simfonice sunt cele mai importante din lume: Orchestra Regala Amsterdam (Concertgebouw Orchestra Amsterdam) Pe 11 aprilie 1888, dupa ani de pregatiri, sala de concerte a orasului Amsterdam, Concertgebouw, a fost in mod oficial deschisa. In sfarsit, Amsterdam avea propriul templu al muzicii si foarte repede s-a dovedit a fi una dintre cele mai bune sali de concerte. O jumatate de an mai tarziu, pe 3 noiembrie 1888, Orchestra Concertgebouw a sustinut primul sau concert. Sub bageta dirijorilor Willem Kes si Willem Mengelberg, in scurt timp a devenit unul dintre cele mai importante ansambluri muzicale ale Europei. In 1897, compozitorul Richard Strauss vorbea de aceasta orchestra in termenii: “cu adevarat magnifica, plina de vigoare si de entuziasmul tineresc”, iar la inceputul secolului XX, sute de compozitori si dirijori au venit in Amsterdam sa cante alaturi de faimoasa orchestra. -

Universi^ International

INFORMATION TO USERS This was produced from a copy of a document sent to us for microfîlming. While the most advanced technological means to photograph and reproduce this document have been used, the quality is heavily dependent upon the quality of the material submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help you understand markings or notations which may appear on this reproduction. 1. The sign or “target” for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is “Missing Page(s)”. If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the Him along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting through an image and duplicating adjacent pages to assure you of complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a round black mark it is an indication that the film inspector noticed either blurred copy because of movement during exposure, or duplicate copy. Unless we meant to delete copyrighted materials that should not have been filmed, you will find a good image of the page in the adjacent frame. 3. When a map, drawing or chart, etc., is part of the material being photo graphed the photographer has followed a definite method in “sectioning” the material. It is customary to begin filming at the upper left hand comer of a large sheet and to continue from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. If necessary, sectioning is continued again—beginning below the first row and continuing on until complete. 4. For any illustrations that cannot be reproduced satisfactorily by xerography, photographic prints can be purchased at additional cost and tipped into your xerographic copy. -

Henk Badings (1907–1987) Trio Für Zwei Sopran- Und Eine Altblockflöte

812 S S A Henk Badings (1907–1987) Trio für zwei Sopran- und eine Altblockflöte for two soprano recorders and one alto recorder Vorwort/Spielanweisungen Das im Jahr 1955 entstandene Trio dieses Heftes ist sowohl für 3 Blockflöten (SSA) als auch für Blockflötenorchester geeignet. Mit wechselnder Besetzung in hohem und tiefen Register sowie Solo- und Tutti-Einsätzen lassen sich aparte dynamische Wir- kungen erzielen. Im 3. Satz empfiehlt es sich außerdem, ein Sopranino hinzuzuziehen. Vorschlag für die Besetzung im Blockflötenorchester: hohes Register Instrument Spieler Sopran 3 Sopran 5 Alt, im 3. Satz ein Sopranino 6 tiefes Register Tenor 1-2 Tenor 2-3 Bass 3 Für die Bassblockflöte liegt eine eigene Stimme bei. Preface/playing instructions The trio in this edition was written in 1955. It can be performed on 3 recorders (SSA) and is also suitable for recorder orchestra. With the changes of high and low registers and the solo and tutti parts special dynamic effects can be achieved. In the third movement it is recommended to use a sopranino. Suggestion for the distribution of parts in a recorder orchestra: high register instrument player soprano 3 soprano 5 treble, in 3rd movement sopranino 6 low register tenor 1-2 tenor 2-3 bass 3 An extra part has been included for the bass recorder. Préface/Consignes d’interprétation Le trio contenu dans ce cahier a été composé en 1955 et se prête aussi bien à une interprétation par trois flûtes à bec (SSA) que par un orchestre de flûtes à bec. Des effets de dynamique intéressants peuvent être obtenus en modifiant la distribution entre les registres inférieur et supérieur et en alternant les parties de solo et de tutti. -

Ferienkurse Für Internationale Neue Musik, 25.8.-29.9. 1946

Ferienkurse für internationale neue Musik, 25.8.-29.9. 1946 Seminare der Fachgruppen: Dirigieren Carl Mathieu Lange Komposition Wolfgang Fortner (Hauptkurs) Hermann Heiß (Zusatzkurs) Kammermusik Fritz Straub (Hauptkurs) Kurt Redel (Zusatzkurs) Klavier Georg Kuhlmann (auch Zusatzkurs Kammermusik) Gesang Elisabeth Delseit Henny Wolff (Zusatzkurs) Violine Günter Kehr Opernregie Bruno Heyn Walter Jockisch Musikkritik Fred Hamel Gemeinsame Veranstaltungen und Vorträge: Den zweiten Teil dieser Übersicht bilden die Veranstaltungen der „Internationalen zeitgenössischen Musiktage“ (22.9.-29.9.), die zum Abschluß der Ferienkurse von der Stadt Darmstadt in Verbindung mit dem Landestheater Darmstadt, der „Neuen Darmstädter Sezession“ und dem Süddeutschen Rundfunk, Radio Frankfurt, durchgeführt wurden. Datum Veranstaltungstitel und Programm Interpreten Ort u. Zeit So., 25.8. Erste Schloßhof-Serenade Kst., 11.00 Ansprache: Bürgermeister Julius Reiber Conrad Beck Serenade für Flöte, Klarinette und Streichorchester des Landes- Streichorchester (1935) theaters Darmstadt, Ltg.: Carl Wolfgang Fortner Konzert für Streichorchester Mathieu Lange (1933) Solisten: Kurt Redel (Fl.), Michael Mayer (Klar.) Kst., 16.00 Erstes Schloß-Konzert mit neuer Kammermusik Ansprachen: Kultusminister F. Schramm, Oberbürger- meister Ludwig Metzger Lehrkräfte der Ferienkurse: Paul Hindemith Sonate für Klavier vierhändig Heinz Schröter, Georg Kuhl- (1938) mann (Kl.) Datum Veranstaltungstitel und Programm Interpreten Ort u. Zeit Hermann Heiß Sonate für Flöte und Klavier Kurt Redel (Fl.), Hermann Heiß (1944-45) (Kl.) Heinz Schröter Altdeutsches Liederspiel , II. Teil, Elisabeth Delseit (Sopr.), Heinz op. 4 Nr. 4-6 (1936-37) Schröter (Kl.) Wolfgang Fortner Sonatina für Klavier (1934) Georg Kuhlmann (Kl.) Igor Strawinsky Duo concertant für Violine und Günter Kehr (Vl.), Heinz Schrö- Klavier (1931-32) ter (Kl.) Mo., 26.8. Komponisten-Selbstporträts I: Helmut Degen Kst., 16.00 Kst., 19.00 Einführung zum Klavierabend Georg Kuhlmann Di., 27.8. -

Literature of the Low Countries

Literature of the Low Countries A Short History of Dutch Literature in the Netherlands and Belgium Reinder P. Meijer bron Reinder P. Meijer, Literature of the Low Countries. A short history of Dutch literature in the Netherlands and Belgium. Martinus Nijhoff, The Hague / Boston 1978 Zie voor verantwoording: http://www.dbnl.org/tekst/meij019lite01_01/colofon.htm © 2006 dbnl / erven Reinder P. Meijer ii For Edith Reinder P. Meijer, Literature of the Low Countries vii Preface In any definition of terms, Dutch literature must be taken to mean all literature written in Dutch, thus excluding literature in Frisian, even though Friesland is part of the Kingdom of the Netherlands, in the same way as literature in Welsh would be excluded from a history of English literature. Similarly, literature in Afrikaans (South African Dutch) falls outside the scope of this book, as Afrikaans from the moment of its birth out of seventeenth-century Dutch grew up independently and must be regarded as a language in its own right. Dutch literature, then, is the literature written in Dutch as spoken in the Kingdom of the Netherlands and the so-called Flemish part of the Kingdom of Belgium, that is the area north of the linguistic frontier which runs east-west through Belgium passing slightly south of Brussels. For the modern period this definition is clear anough, but for former times it needs some explanation. What do we mean, for example, when we use the term ‘Dutch’ for the medieval period? In the Middle Ages there was no standard Dutch language, and when the term ‘Dutch’ is used in a medieval context it is a kind of collective word indicating a number of different but closely related Frankish dialects. -

Historie & Kroniek Concertgebouw Enz Compleet Gratis Epub, Ebook

HISTORIE & KRONIEK CONCERTGEBOUW ENZ COMPLEET GRATIS Auteur: none Aantal pagina's: 542 pagina's Verschijningsdatum: none Uitgever: Uitgeverij Walburg Pers B.V.||9789060115800 EAN: nl Taal: Link: Download hier Hendrik (Han Henri) de Booy (1867-1964) Namens de raad spreekt de heer Koopmans. Na de installatie wordt een drukbezochte receptie gehouden. Behandeld worden o. Hij heeft zijn benoeming bij Koninklijk Besluit van 18 februari ontvangen. De Nieuwe Schiedamsche Courant geeft een uitgebreide beschrijving van dit grootste Nederlandse zeeschip. Scheffer viert zijn jarig jubileum bij de drukkerij van de firma Gebr. Niemantsverdriet uit Vlaardingen vragen vergunning voor de oprichting van een suikerwerkfabriek aan de Westerkade Witkamp, één der directeuren van NV Distilleerderij Wed. Eelaart, overlijdt op jarige leeftijd. Ingenool in hotel Beijersbergen een lezing over de toekomst van het middenstandsbedrijf in verband met de toeneming van het aantal warenhuizen, filiaalbedrijven en verbruiks-coöperaties in stad en land. Geen enkel ontwerp is bekroond. Pappers woonachtig in de Kleine Baan te Schiedam raakt op de onbewaakte overweg te Kethel onder de trein en verongelukt dodelijk. Het kampioenschap en het 9-jarig bestaan worden onder leiding van voorzitter M. Kuijpers, Wed. Kooijman-van der Beek en Gebrs. Het woord wordt gevoerd door voorzitter Th. Teeuw, leraar aan de Ambachtsschool aan de St. Liduinastraat, viert zijn zilveren jubileum. Schaeffer een feestavond in Musis Sacrum. Kranenburg te Zuidland gaat voor f. Näring gaat als laagste inschrijver voor f. Hulsman vraagt vergunning voor oprichting van een rijwielfabriek in pand Buitenhavenweg Bouw vraagt een schenkvergunning voor het schenken van licht alcoholische dranken in het pand Dam Schiedam, voor de eerste maal onder leiding van voorzitster mevr. -

Chapter 1: Schoenberg the Conductor

Demystifying Schoenberg's Conducting Avior Byron Video: Silent, black and white footage of Schönberg conducting the Los Angeles Philharmonic in a rehearsal of Verklärte Nacht, Op. 4 in March 1935. Audio ex. 1: Schoenberg conducting Pierrot lunaire, ‘Eine blasse Wäscherin’, Los Angeles, CA, 24 September 1940. Audio ex. 2: Schoenberg conducting Verklärte Nacht Op. 4, Berlin, 1928. Audio ex. 3: Schoenberg conducting Verklärte Nacht Op. 4, Berlin, 1928. In 1975 Charles Rosen wrote: 'From time to time appear malicious stories of eminent conductors who have not realized that, in a piece of … Schoenberg, the clarinettist, for example, picked up an A instead of a B-flat clarinet and played his part a semitone off'.1 This widespread anecdote is often told about Schoenberg as a conductor. There are also music critics who wrote negatively and quite decisively about Schoenberg's conducting. For example, Theo van der Bijl wrote in De Tijd on 7 January 1921 about a concert in Amsterdam: 'An entire Schoenberg evening under the direction of the composer, who unfortunately is not a conductor!' Even in the scholarly literature one finds declarations from time to time that Schoenberg was an unaccomplished conductor.2 All of this might have contributed to the fact that very few people now bother taking Schoenberg's conducting seriously.3 I will challenge this prevailing negative notion by arguing that behind some of the criticism of Schoenberg's conducting are motives, which relate to more than mere technical issues. Relevant factors include the way his music was received in general, his association with Mahler, possibly anti-Semitism, occasionally negative behaviour of performers, and his complex relationship with certain people.