1494:1 Russellville, Arkansas

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Psalms in Our Times: an Online Study of the Psalms During the COVID-19 Pandemic

The Psalms in Our Times: An Online Study of the Psalms During the COVID-19 Pandemic Agenda for Weeks 1-3: - Series overview (week 1 only) - Check-in and review - Introduction of the Week’s Psalm(s) - Discussion and Question & Answer Agenda for Week 4: - Check-in and review - Sharing of Psalms (optional) - Wrap-up Sources for Psalm texts: - Book of Common Prayer (Psalter, pages 582-808) - Oremus Bible Browser (bible.oremus.org) Participants are invited to this document and take notes (or not) and work on creating their own Psalm for Session 4 (or not). All videos will be posted to the “St. John’s Episcopal Church Lancaster” YouTube page so participants can review or catch up as needed. Session 1 Psalm 29 Psalm 146 1Ascribe to the Lord, O heavenly beings, 1Praise the Lord! Praise the Lord, O my ascribe to the Lord glory and strength. soul! 2Ascribe to the Lord the glory of his name; 2I will praise the Lord as long as I live; I will worship the Lord in holy splendor. sing praises to my God all my life long. 3The voice of the Lord is over the waters; 3Do not put your trust in princes, in the God of glory thunders, the Lord, over mortals, in whom there is no help. mighty waters. 4When their breath departs, they return to 4The voice of the Lord is powerful; the voice the earth; on that very day their plans of the Lord is full of majesty. perish. 5The voice of the Lord breaks the cedars; 5Happy are those whose help is the God of the Lord breaks the cedars of Lebanon. -

Service Music

Service Music 386 387 388 389 390 391 392 393 394 395 396 397 398 399 400 401 402 403 404 405 406 407 408 409 410 411 412 413 414 415 416 417 418 419 420 421 422 423 424 425 426 427 428 429 430 431 432 433 434 435 436 437 Indexes Copyright Permissions Copyright Page Under Construction 441 442 Chronological Index of Hymn Tunes Plainsong Hymnody 1543 The Law of God Is Good and Wise, p. 375 800 Come, Holy Ghost, Our Souls Inspire 1560 That Easter Day with Joy Was Bright, p. 271 plainsong, p. 276 1574 In God, My Faithful God, p. 355 1200?Jesus, Thou Joy of Loving Hearts 1577 Lord, Thee I Love with All My Heart, p. 362 Sarum plainsong, p. 211 1599 How Lovely Shines the Morning Star, p. 220 1250 O Come, O Come Emmanuel 1599 Wake, Awake, for Night Is Flying, p. 228 13th century plainsong, p. 227 1300?Of the Father's Love Begotten Calvin's Psalter 12th to 15th century tropes, p. 246 1542 O Food of Men Wayfaring, p. 213 1551 Comfort, Comfort Ye My People, p. 226 Late Middle Ages and Renaissance Melodies 1551 O Gladsome Light, p. 379 English 1551 Father, We Thank Thee Who Hast Planted, p. 206 1415 O Love, How Deep, How Broad, How High! English carol, p. 317 Bohemian Brethren 1415 O Wondrous Type! O Vision Fair! 1566 Sing Praise to God, Who Reigns Above, p. 324 English carol, p. 320 German Unofficial English Psalters and Hymnbooks, 1560-1637 1100 We Now Implore the Holy Ghost 1567 Lord, Teach Us How to Pray Aright -Thomas Tallis German Leise, p. -

Concordia Journal

CONCORDIA JOURNAL Volume 28 July 2002 Number 3 CONTENTS ARTICLES The 1676 Engraving for Heinrich Schütz’s Becker Psalter: A Theological Perspective on Liturgical Song, Not a Picture of Courtly Performers James L. Brauer ......................................................................... 234 Luther on Call and Ordination: A Look at Luther and the Ministry Markus Wriedt ...................................................................... 254 Bridging the Gap: Sharing the Gospel with Muslims Scott Yakimow ....................................................................... 270 SHORT STUDIES Just Where Was Jonah Going?: The Location of Tarshish in the Old Testament Reed Lessing .......................................................................... 291 The Gospel of the Kingdom of God Paul R. Raabe ......................................................................... 294 HOMILETICAL HELPS ..................................................................... 297 BOOK REVIEWS ............................................................................... 326 BOOKS RECEIVED ........................................................................... 352 CONCORDIA JOURNAL/JULY 2002 233 Articles The 1676 Engraving for Heinrich Schütz’s Becker Psalter: A Theological Perspective on Liturgical Song, Not a Picture of Courtly Performers James L. Brauer The engraving at the front of Christoph Bernhard’s Geistreiches Gesang- Buch, 1676,1 (see PLATE 1) is often reproduced as an example of musical PLATE 1 in miniature 1Geistreiches | Gesang-Buch/ -

Psalm Extracts

Longman’s Charity ~ Psalms A Novel about Landscape and Childhood, Sanity and Abuse, Truth and Redemption Paul Brazier The extracts from the psalms that open each chapter were based, initially, on existing translations, however I then re-translated by going back to the original Greek translation of the Hebrew Bible: The Septuagint, from the late 2nd century BC. Prologue—A Welcoming Κύριε, μὴ τῷ θυμῷ σου ἐλέγξῃς με “Have mercy on me, O Lord, for I am weak; μηδὲ τῇ ὀργῇ σου παιδεύσῃς με. O Lord, heal me, for my very bones are troubled.” PSALM 6 vv. 2 PSALM 6:2 PART ONE THE LAND & THE CHILD ἰδοὺ γὰρ ἐν ἀνομίαις συνελήμφθην, καὶ ἐν ἁμαρτίαις “Behold, I was brought forth in iniquity, and in sin my ἐκίσσησέν με ἡ μήτηρ μου. mother did conceive me.” PSALM 50 (51) vv. 5 PSALM 51:5 Chapter 1 καὶ ἔστησεν αὐτὴν τῷ Ιακωβ εἰς πρόσταγμα καὶ τῷ “He sends the springs into the valleys, they flow among Ισραηλ διαθήκην αἰώνιον λέγων Σοὶ δώσω τὴν γῆν the hills. They give drink to every beast of the field . Χανααν σχοίνισμα κληρονομίας ὑμῶν ... He causes the grass to grow for the cattle, and ἐξανατέλλων χόρτον τοῖς κτήνεσιν καὶ χλόην τῇ vegetation for man, that he may bring forth food from δουλείᾳ τῶν ἀνθρώπων τοῦ ἐξαγαγεῖν ἄρτον ἐκ τῆς the earth...” γῆς. PSALM 103 (104) vv. 10-11a, &, 14 PSALM 104:10-11a & 14 Chapter 2 ἰδοὺ γὰρ ἐν ἀνομίαις συνελήμφθην, καὶ ἐν ἁμαρτίαις “Behold, I was brought forth in iniquity, and in sin my ἐκίσσησέν με ἡ μήτηρ μου. -

18Summer-Vol24-No3-TM.Pdf

Theology Matters Vol 24, No. 3 Summer 2018 Rediscovering the Office of Elder The Shepherd Model by Eric Laverentz At the center of our name, tradition, identity, and ethos guard the purity of the church in the lives of its as Presbyterians is a term that has lost almost all members. In dealing with offenses, the session holds connection with what it meant to most who have called both judiciary and executive authority. But the most themselves Presbyterians over the last five centuries. important function of elders is to watch over the flock, Even to many of our parents and grandparents being a of which they are under-shepherds, guarding, “presbyter” or “elder” meant something quite different counseling, comforting, instructing, encouraging, and than it means to most of us today. admonishing, as circumstances require. The penalties imposed on wrongdoers are censure, suspension from The not too distant past paints a picture of elders vested the communion of the Church, and excommunication.1 with spiritual authority who were deeply enmeshed in the lives of people. This is very different from the As foreign as this description of duties sounds to 21st service rendered in most elder-led churches today. We century ears, it was not the elders of First Presbyterian have seen a total shift in understanding of what it Church, Dayton, Ohio, in the 1880s who were guarding means to be an elder over the last generation or two. the purity of their members and exercising discipline The shift is so complete that few of us have any that were out of touch with the historical and Biblical institutional memory of the way it used to be. -

Finding God in the Book of Moses

Finding God in The Book of Moses Santa Barbara Community Church Winter / Spring Calendar 2007 Teaching Study Text Title Date 1/28 1 Genesis 1:1-2:3 Finding God in the Beginning 2/4 2 Genesis 2-3 In the Garden: God Betrayed 2/11 3 Genesis 11:27— Calling a Chaldean: God’s Promise 12:9 2/18 4 Genesis 21—22 A Son Called Laughter: God Provides 2/25 5 Genesis 16; Hagar and Ishmael: God Hears 21:8-21 3/4 6 Genesis 25:19- Jacob’s Blessing: God Chooses 34; 26:34—28:5 3/11 7 Genesis 42—47 Joseph: God Plans 3/18 8 Exodus 1-2 Moses: God Knows 3/25 9 Exodus 11-12 Passover: God Delivers 4/1 10 Exodus 19 Smoke on the Mountain: God Unapproachable 4/8 11 Exodus 20:1-21 The Ten Words: God Wills 4/15 Easter 4/22 12 Exodus 24:15— The Tent: God Dwells 27:19 4/29 Retreat Sunday The text of this study was written and prepared by Reed Jolley. Thanks to DeeDee Underwood, Erin Patterson, Bonnie Fear and Susi Lamoutte for proof reading the study. And thanks to Kat McLean (cover and studies 1,4,8, 11), Kaitee Hering (studies 3,5,7,10), and Paul Benthin (studies 2,6,9,12) for providing the illustrations. All Scripture citations unless otherwise noted are from the English Standard Version. May God bless Santa Barbara Community Church as we study his word! SOURCES/ABBREVIATIONS Childs Brevard Childs. The Book of Exodus: A Critical, Theological Commentary, Westminster, 1967 Cole R. -

Psalm 100 Sweelinck, Ed

CM9412 Psalm 100 Sweelinck, ed. Hooper / SAATB a cappella Psalm 100 Vous tous qui la terr’ habitez Jan Pieterszoon Sweelinck For RANDALL HOOPER unlawfulpromotional SAATB Voices a cappella Duration: 3:49 to RANGES: copy use or only print FREE MP3 rehearsal and accompaniments www.carlfischer.com 2 About the Composer Jan Pieterszoon Sweelinck (1562-1621) was born and raised in Amsterdam. He worked as the organist at the Oude Kerk in Amsterdam from ca. 1580 until his death in 1621. Because the Calvinists saw the organ as a worldly instrument and forbade its use during religious services, he was actually a civil servant employed by the city of Amsterdam. It is assumed that his duties were to provide music twice daily in the church, an hour in the morning and in the evening. When there was a service, this hour came before and/or after the service. As well as being one of the most famous organists and teachers of this time, Sweelinck was the last and most important com- poser of the musically rich golden era of the Netherlanders. All of his vocal works Forwere printed in his lifetime. His polyphonic setting of Psalter has been called a monu- ment of Netherlandish music, unequalled in the sphere of sacred polyphony. From the outset he intended to set the entire Psalter, and he dedicated much of his creative life unlawfulto this music.promotional The texts are from the French metrical Psalter, not the Dutch version which was used in most Dutch churches. This is probably because the psalms were not intended for use in public Calvinist services but rather within a circle of well-to-do musical amateurs among whom French was the preferred language. -

New England Church ' Relations^ and Continuity in Early Congregational History

New England Church ' Relations^ and Continuity in Early Congregational History BY RAYMOND PIIINEAS STEARNS AND DAVID HOLMKS BRAWNER N HIS ground-breaking study of early Engiish dissenters, I ChampHn Barrage announced a half-century ago that the "beginnings of Independency or Congregationalism, are not, as heretofore, traced to the Brownists or Barrowists, but to the Congregational Puritanism advocated by Henry Jacob and William Bradshaw about 1604 and 1605, and later put in practice by various Puritan congregations on the Continent, when it was brought to America and back into England."^ This evolutionary scheme, as developed and substantiated in later studies, has by now acquired considerable authority. The late Perry Miller's Orthodoxy in Aíassachiíseits was ''a development of the hints" received from Burrage and others; Charles M. Andrews adopted a simiiar point of view; and in 1947 Professor Thomas JeiTer- son Wertenbaker went so far as to write that ''before the end of the reign of James Í, English Congregationalism, the Congregationalism which was transplanted in New England, had assumed its final form."- Obviously, the Burrage thesis has proved a boon to his- torians in that it provided a framework within which they ^ Thi Early English DlnenUrs in the Light of Recent Research, I$¡o~i64^i (3 vols., Cam- bridge, England, I'.Jiz), I, 33. "^ Orikodoxy in Massachuseiis, i6^^o-i6so {Cambridge, NTass., 1933), p. sv; Andrews, The Colonial P/^rizd i-ij American History {4 vois., New Haven, 1934--193S), I, 379, o. 2; Wertcnbaker, The Puritan Oligarchy {KKVÍ York, n.d.), p. 26. 14 AMERICAN ANTIQUARIAN SOCIETY [April, have been able to work out the early history of non-separat- ing Congregationalism as a continuous development, inde- pendent of the Separatist movement. -

Psalm 1 the Two Ways 1 Happy Are Those Who Do Not Follow the Advice

Psalm 1 The Two Ways 1 Happy are those who do not follow the advice of the wicked, or take the path that sinners tread, or sit in the seat of scoffers; 2 but their delight is in the law of the LORD, and on his law they meditate day and night. 3 They are like trees planted by streams of water, which yield their fruit in its season, and their leaves do not wither. In all that they do, they prosper. 4 The wicked are not so, but are like chaff that the wind drives away. 5 Therefore the wicked will not stand in the judgment, nor sinners in the congregation of the righteous; 6 for the LORD watches over the way of the righteous, but the way of the wicked will perish. Psalm 98 Praise the Judge of the World 1 O sing to the LORD a new song, for he has done marvellous things. His right hand and his holy arm have gotten him victory. 2 The LORD has made known his victory; he has revealed his vindication in the sight of the nations. 3 He has remembered his steadfast love and faithfulness to the house of Israel. All the ends of the earth have seen the victory of our God. 4 Make a joyful noise to the LORD, all the earth; break forth into joyous song and sing praises. 5 Sing praises to the LORD with the lyre, with the lyre and the sound of melody. 6 With trumpets and the sound of the horn make a joyful noise before the King, the LORD. -

Cantus Christi Copyright © 2002 Christ Church, Moscow, Idaho 2004 Revised Edition

Cantus Christi Copyright © 2002 Christ Church, Moscow, Idaho 2004 Revised Edition Published by Canon Press P.O. Box 8729, Moscow, ID 83843. 800–488–2034 www.canonpress.org 05 06 07 08 09 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopy, recording, or otherwise, without prior permission of the author, except as provided by USA copyright law. The publisher gratefully acknowledges permission to reprint texts, tunes and arrangements granted by the publishers, organizations and individuals listed on pages xviii and 443–445. Every effort has been made to secure current copyright permission information on the Psalms, hymns, and service music used. If any right has been infringed, the publisher promises to make the correction in subsequent printings as the additional information is received. ISBN: Cantus Christi (clothbound) 1–59128–003- 6 ISBN: Cantus Christi (accompanist’s edition) 1–59128–004–4 Tabl e of Conte nt s Manifesto on Psalms and Hymns by Douglas Wilson . v Introduction to Musical Style by Dr. Louis Schuler . ix List of Abbreviations . xvii Copyright Holders . xviii Section I Psalms . 1 Section II Hymns . 197 Baptism . 198 Communion . 202 Advent . 218 Christmas . 230 Epiphany . 251 Christ’s Passion . 255 Triumphal Entry . 268 Resurrection . 269 Ascension . 274 Pentecost . 276 All Saints . 280 Thanksgiving . 283 Adoration . 286 Supplication . 336 Evening Hymns . 377 Section III Service Music . 385 Indexes . 441 Copyright Permissions . 443 Chronological Index of Hymn Tunes . 446 Index of Authors, Composers, and Sources . -

Copyright by Gary Dean Beckman 2007

Copyright by Gary Dean Beckman 2007 The Dissertation Committee for Gary Dean Beckman Certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: The Sacred Lute: Intabulated Chorales from Luther’s Age to the beginnings of Pietism Committee: ____________________________________ Andrew Dell’ Antonio, Supervisor ____________________________________ Susan Jackson ____________________________________ Rebecca Baltzer ____________________________________ Elliot Antokoletz ____________________________________ Susan R. Boettcher The Sacred Lute: Intabulated Chorales from Luther’s Age to the beginnings of Pietism by Gary Dean Beckman, B.A.; M.A. Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Texas at Austin December 2007 Acknowledgments I would like to acknowledge Dr. Douglas Dempster, interim Dean, College of Fine Arts, Dr. David Hunter, Fine Arts Music Librarian and Dr. Richard Cherwitz, Professor, Department of Communication Studies Coordinator from The University of Texas at Austin for their help in completing this work. Emeritus Professor, Dr. Keith Polk from the University of New Hampshire, who mentored me during my master’s studies, deserves a special acknowledgement for his belief in my capabilities. Olav Chris Henriksen receives my deepest gratitude for his kindness and generosity during my Boston lute studies; his quite enthusiasm for the lute and its repertoire ignited my interest in German lute music. My sincere and deepest thanks are extended to the members of my dissertation committee. Drs. Rebecca Baltzer, Susan Boettcher and Elliot Antokoletz offered critical assistance with this effort. All three have shaped the way I view music. -

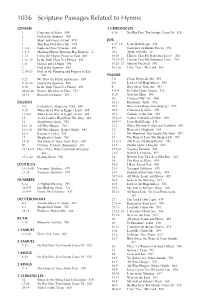

1036 Scripture Passages Related to Hymns

1036 Scripture Passages Related to Hymns GENESIS 2 CHRONICLES 1: Cantemos al Señor 695 6:14 No Hay Dios Tan Grande Como Tú 525 1: God of the Sparrow 485 1: Many and Great, O God 479 JOB 1: This Day God Gives Me 693 3:17–18 Jesus Shall Reign 478 1:1–2 Soplo del Dios Viviente 458 8:9 Cantemos un Himno Nuevo 431 1:3–5 Morning Hymn (Morning Has Broken) 4 14:1 Abide with Me 21 1:12 I Sing the Mighty Power of God 481 19:25 I Know That My Redeemer Lives! 434 1:12–13 In the Bulb There Is a Flower 491 19:25–27 I Know That My Redeemer Lives 795 1:31 Gracias por el Amor 696 19:25–27 Song of Farewell 796 2: God of the Sparrow 485 42:1–6 I Say “Yes,” My Lord 565 2:18–23 God, in the Planning and Purpose of Life 793 PSALMS 8:22 We Plow the Fields and Scatter 659 3:4 Christ Be beside Me 553 9:12–16 God of the Sparrow 485 4:8 Lord of All Hopefulness 556 9:15 In the Bulb There Is a Flower 491 8: How Great Thou Art 483 28:10–22 Nearer, My God, to Thee 794 8:4–5 El Cielo Canta Alegría 516 28:12 Blessed Assurance 582 9:10 You Are Mine 596 16: Center of My Life 566 EXODUS 16:11 Enséñame, Señor 561 3:5 Cantando la Alegría de Vivir 680 18:3 How Can I Keep from Singing? 570 6:10 When Israel Was in Egypt’s Land 488 19:2 Cantemos al Señor 695 11:4–8 When Israel Was in Egypt’s Land 488 19:2 Canticle of the Sun 482 15: At the Lamb’s High Feast We Sing 449 19:2–4 Vamos Cantando al Señor 689 16: Shepherd of Souls 755 19:5–7 Jesus Shall Reign 478 16:1–21 All Who Hunger 769 22:2 When My Soul Is Sore and Troubled 559 16:1–21 All Who Hunger, Gather Gladly 684 23: Heart