The Journal of Ottoman Studies Xii

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

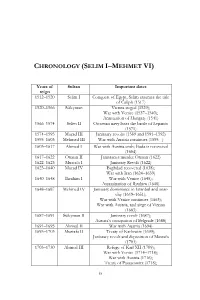

Selim I–Mehmet Vi)

CHRONOLOGY (SELIM I–MEHMET VI) Years of Sultan Important dates reign 1512–1520 Selim I Conquest of Egypt, Selim assumes the title of Caliph (1517) 1520–1566 Süleyman Vienna sieged (1529); War with Venice (1537–1540); Annexation of Hungary (1541) 1566–1574 Selim II Ottoman navy loses the battle of Lepanto (1571) 1574–1595 Murad III Janissary revolts (1589 and 1591–1592) 1595–1603 Mehmed III War with Austria continues (1595– ) 1603–1617 Ahmed I War with Austria ends; Buda is recovered (1604) 1617–1622 Osman II Janissaries murder Osman (1622) 1622–1623 Mustafa I Janissary Revolt (1622) 1623–1640 Murad IV Baghdad recovered (1638); War with Iran (1624–1639) 1640–1648 İbrahim I War with Venice (1645); Assassination of İbrahim (1648) 1648–1687 Mehmed IV Janissary dominance in Istanbul and anar- chy (1649–1651); War with Venice continues (1663); War with Austria, and siege of Vienna (1683) 1687–1691 Süleyman II Janissary revolt (1687); Austria’s occupation of Belgrade (1688) 1691–1695 Ahmed II War with Austria (1694) 1695–1703 Mustafa II Treaty of Karlowitz (1699); Janissary revolt and deposition of Mustafa (1703) 1703–1730 Ahmed III Refuge of Karl XII (1709); War with Venice (1714–1718); War with Austria (1716); Treaty of Passarowitz (1718); ix x REFORMING OTTOMAN GOVERNANCE Tulip Era (1718–1730) 1730–1754 Mahmud I War with Russia and Austria (1736–1759) 1754–1774 Mustafa III War with Russia (1768); Russian Fleet in the Aegean (1770); Inva- sion of the Crimea (1771) 1774–1789 Abdülhamid I Treaty of Küçük Kaynarca (1774); War with Russia (1787) -

THE JOURNAL of OTTOMAN .STUDIES Xx

OSMANLI ARAŞTIRMALARI xx Neşir Heyeti - Editorial Board Halil İNALerK-Nejat GÖYÜNÇ Heath W. LOWRY- İsmail ER ÜNSAL Klaus KREISER- A. Atilla ŞENTÜRK THE JOURNAL OF OTTOMAN .STUDIES xx İstanbul - 2000 Sahibi : ENDERUN KİTABEVİ adına İsmail ÖZDOGAN Tel: + 90 212 528 63 18 Fax :++- 90 212 528 63 17 Yazı İ ş l eri Sorumlusu : Nejat GÖYÜNÇ Tel : + 90 216 333 91 16 Basıldı ğ ı Yer : KİTAP MATBAACILIK San. ve Tic. Ltd. Şti . Tel: + 90 212 567 48 84 Cilt: FATiH MÜCELLiT Matbaacılık ve Ambalaj San. ve Tic. Ltd. Şti. Tel : + 90 501 28 23 - 61 2 86 71 Yaz ı şma Adresi: ENDERUN Kİ TABEVİ, BüyUk Reşitpaşa Cad. Yümni İş Merkezi 22/46 Rt!yaz ıı - istanbul THE LİFE OF KÖPRÜLÜZADE FAZIL MUSTAFA PASHA AND HIS REFORMS (1637-1691) Fehmi YILMAZ His life before his vizierate The Köprülüs are known as an eminent vizier family in the Ottoman state due to their reforming initiatives especially when the state encountered serious internal and external problems in the second half of the seventeenth century. The name of Köprülü comes from the town of Köprü Iocated near Amasya. Köprülü Mehmed Pasha, who gave his name to the family, was brought to İstanbul from Albania as a devshirme recruit when he was a child, and he was trained in the Acemi Oglanlar Odjagı of the pala:ce. He spent a significant period of his youthin the palace. He was appointed as hassa cook in the Matbah-ı Amire in 1623. He also joined the retinue of Boshnak Hüsrev Pas ha who was employed in the same period·in the Has-Oda and who would later become a grand vizier. -

Rebellion, Janissaries and Religion in Sultanic Legitimisation in the Ottoman Empire

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Istanbul Bilgi University Library Open Access “THE FURIOUS DOGS OF HELL”: REBELLION, JANISSARIES AND RELIGION IN SULTANIC LEGITIMISATION IN THE OTTOMAN EMPIRE UMUT DENİZ KIRCA 107671006 İSTANBUL BİLGİ ÜNİVERSİTESİ SOSYAL BİLİMLER ENSTİTÜSÜ TARİH YÜKSEK LİSANS PROGRAMI PROF. DR. SURAIYA FAROQHI 2010 “The Furious Dogs of Hell”: Rebellion, Janissaries and Religion in Sultanic Legitimisation in the Ottoman Empire Umut Deniz Kırca 107671006 Prof. Dr. Suraiya Faroqhi Yard. Doç Dr. M. Erdem Kabadayı Yard. Doç Dr. Meltem Toksöz Tezin Onaylandığı Tarih : 20.09.2010 Toplam Sayfa Sayısı: 139 Anahtar Kelimeler (Türkçe) Anahtar Kelimeler (İngilizce) 1) İsyan 1) Rebellion 2) Meşruiyet 2) Legitimisation 3) Yeniçeriler 3) The Janissaries 4) Din 4) Religion 5) Güç Mücadelesi 5) Power Struggle Sosyal Bilimler Enstitüsü’nde Tarih Yüksek Lisans derecesi için Umut Deniz Kırca tarafından Mayıs 2010’da teslim edilen tezin özeti. Başlık: “Cehennemin Azgın Köpekleri”: Osmanlı İmparatorluğu’nda İsyan, Yeniçeriler, Din ve Meşruiyet Bu çalışma, on sekizinci yüzyıldan ocağın kaldırılmasına kadar uzanan sürede patlak veren yeniçeri isyanlarının teknik aşamalarını irdelemektedir. Ayrıca, isyancılarla saray arasındaki meşruiyet mücadelesi, çalışmamızın bir diğer konu başlığıdır. Başkentte patlak veren dört büyük isyan bir arada değerlendirilerek, Osmanlı isyanlarının karakteristik özelliklerine ve isyanlarda izlenilen meşruiyet pratiklerine ışık tutulması hedeflenmiştir. Çalışmamızda kullandığımız metot dâhilinde, 1703, 1730, 1807 ve 1826 isyanlarını konu alan yazma eserler karşılaştırılmış, müelliflerin, eserlerini oluşturdukları süreçteki niyetleri ve getirmiş oldukları yorumlara odaklanılmıştır. Argümanların devamlılığını gözlemlemek için, 1703 ve 1730 isyanları ile 1807 ve 1826 isyanları iki ayrı grupta incelenmiştir. 1703 ve 1730 isyanlarının ortak noktası, isyancıların kendi çıkarları doğrultusunda padişaha yakın olan ve rakiplerini bu sayede eleyen politik kişilikleri hedef almalarıdır. -

Mighty Guests of the Throne Note on Transliteration

Sultan Ahmed III’s calligraphy of the Basmala: “In the Name of God, the All-Merciful, the All-Compassionate” The Ottoman Sultans Mighty Guests of the Throne Note on Transliteration In this work, words in Ottoman Turkish, including the Turkish names of people and their written works, as well as place-names within the boundaries of present-day Turkey, have been transcribed according to official Turkish orthography. Accordingly, c is read as j, ç is ch, and ş is sh. The ğ is silent, but it lengthens the preceding vowel. I is pronounced like the “o” in “atom,” and ö is the same as the German letter in Köln or the French “eu” as in “peu.” Finally, ü is the same as the German letter in Düsseldorf or the French “u” in “lune.” The anglicized forms, however, are used for some well-known Turkish words, such as Turcoman, Seljuk, vizier, sheikh, and pasha as well as place-names, such as Anatolia, Gallipoli, and Rumelia. The Ottoman Sultans Mighty Guests of the Throne SALİH GÜLEN Translated by EMRAH ŞAHİN Copyright © 2010 by Blue Dome Press Originally published in Turkish as Tahtın Kudretli Misafirleri: Osmanlı Padişahları 13 12 11 10 1 2 3 4 All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system without permission in writing from the Publisher. Published by Blue Dome Press 535 Fifth Avenue, 6th Fl New York, NY, 10017 www.bluedomepress.com Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Available ISBN 978-1-935295-04-4 Front cover: An 1867 painting of the Ottoman sultans from Osman Gazi to Sultan Abdülaziz by Stanislaw Chlebowski Front flap: Rosewater flask, encrusted with precious stones Title page: Ottoman Coat of Arms Back flap: Sultan Mehmed IV’s edict on the land grants that were deeded to the mosque erected by the Mother Sultan in Bahçekapı, Istanbul (Bottom: 16th century Ottoman parade helmet, encrusted with gems). -

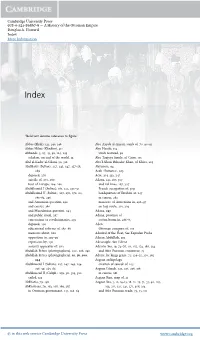

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-89867-6 — a History of the Ottoman Empire Douglas A

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-89867-6 — A History of the Ottoman Empire Douglas A. Howard Index More Information Index “Bold text denotes reference to figure” Abbas (Shah), 121, 140, 148 Abu Ayyub al-Ansari, tomb of, 70, 90–91 Abbas Hilmi (Khedive), 311 Abu Hanifa, 114 Abbasids, 3, 27, 45, 92, 124, 149 tomb restored, 92 scholars, on end of the world, 53 Abu Taqiyya family, of Cairo, 155 Abd al-Kader al-Gilani, 92, 316 Abu’l-Ghazi Bahadur Khan, of Khiva, 265 Abdülaziz (Sultan), 227, 245, 247, 257–58, Abyssinia, 94 289 Aceh (Sumatra), 203 deposed, 270 Acre, 214, 233, 247 suicide of, 270, 280 Adana, 141, 287, 307 tour of Europe, 264, 266 and rail lines, 287, 307 Abdülhamid I (Sultan), 181, 222, 230–31 French occupation of, 309 Abdülhamid II (Sultan), 227, 270, 278–80, headquarters of Ibrahim at, 247 283–84, 296 in census, 282 and Armenian question, 292 massacre of Armenians in, 296–97 and census, 280 on hajj route, 201, 203 and Macedonian question, 294 Adana, 297 and public ritual, 287 Adana, province of concessions to revolutionaries, 295 cotton boom in, 286–87 deposed, 296 Aden educational reforms of, 287–88 Ottoman conquest of, 105 memoirs about, 280 Admiral of the Fleet, See Kapudan Pasha opposition to, 292–93 Adnan Abdülhak, 319 repression by, 292 Adrianople. See Edirne security apparatus of, 280 Adriatic Sea, 19, 74–76, 111, 155, 174, 186, 234 Abdullah Frères (photographers), 200, 288, 290 and Afro-Eurasian commerce, 74 Abdullah Frères (photographers), 10, 56, 200, Advice for kings genre, 71, 124–25, 150, 262 244 Aegean archipelago -

Self and Others: the Diary of a Dervish in Seventeenth Century

Maisonneuve & Larose Self and Others: The Diary of a Dervish in Seventeenth Century Istanbul and First-Person Narratives in Ottoman Literature Author(s): Cemal Kafadar Reviewed work(s): Source: Studia Islamica, No. 69 (1989), pp. 121-150 Published by: Maisonneuve & Larose Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/1596070 . Accessed: 30/09/2012 16:26 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp . JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Maisonneuve & Larose is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Studia Islamica. http://www.jstor.org SELF AND OTHERS: THE DIARY OF A DERVISH IN SEVENTEENTH CENTURY ISTANBUL AND FIRST-PERSON NARRATIVES IN OTTOMAN LITERATURE Ottoman literary history,indeed all Ottoman cultural history, has been traditionallyviewed within the frameworkof a dualistic schema: courtly (high, learned, orthodox, cosmopolitan, polished, artificial, stiff,inaccessible to the masses) versus popular (folk, tainted with unorthodox beliefs-practicesand superstitions, but pure and simple in the sense of preserving "national" spirit, natural, honest). This schema took shape under the influenceof two major factors. On the one hand, there was the impact of the two-tiered model of cultural and religious studies in nineteenth- century Europe with its relatively sharp distinction between "high" and "low" traditions.(') On the other, there were the ideological needs of incipientTurkish nationalism to distance itself from the Ottoman elite while embracing some form of populism. -

The Ottoman Empire, 1700–1922, Second Edition

This page intentionally left blank The Ottoman Empire, 1700–1922 The Ottoman Empire was one of the most important non-Western states to survive from medieval to modern times, and played a vital role in European and global history. It continues to affect the peoples of the Middle East, the Balkans, and Central and Western Europe to the present day. This new survey examines the major trends during the latter years of the empire; it pays attention to gender issues and to hotly de- bated topics such as the treatment of minorities. In this second edition, Donald Quataert has updated his lively and authoritative text, revised the bibliographies, and included brief bibliographies of major works on the Byzantine Empire and the post–Ottoman Middle East. This ac- cessible narrative is supported by maps, illustrations, and genealogical and chronological tables, which will be of help to students and non- specialists alike. It will appeal to anyone interested in the history of the Middle East. DONALD QUATAERT is Professor of History at Binghamton University, State University of New York. He has published many books on Middle East and Ottoman history, including An Economic and Social History of the Ottoman Empire, 1300–1914 (1994). NEW APPROACHES TO EUROPEAN HISTORY Series editors WILLIAM BEIK Emory University T . C . W . BLANNING Sidney Sussex College, Cambridge New Approaches to European History is an important textbook series, which provides concise but authoritative surveys of major themes and problems in European history since the Renaissance. Written at a level and length accessible to advanced school students and undergraduates, each book in the series addresses topics or themes that students of Eu- ropean history encounter daily: the series will embrace both some of the more “traditional” subjects of study, and those cultural and social issues to which increasing numbers of school and college courses are devoted. -

Leer Artículo Completo

REAL ACADEMIA MATRITENSE DE HERÁLDICA Y GENEALOGÍA La Casa de Osmán. La sucesión de los Sultanes Otomanos tras la caída del Imperio. Por José María de Francisco Olmos Académico de Número MADRID MMIX José María de Francisco Olmos A raíz de la reciente muerte en Estambul el 23 de septiembre pasado (2009) de Ertugrul Osman V, jefe de la Casa de Osmán o de la Casa Imperial de los Otomanos, parece apropiado hacer unos comentarios sobre esta dinastía turca y musulmana que fue sin duda una de las grandes potencias del mundo moderno. Sus orígenes son medievales y se encuentran en una tribu turca (los ughuz de Kayi) que emigró desde las tierras del Turquestán hacia occidente durante el siglo XII. Su líder, Suleyman, los llevó hasta Anatolia hacia 1225, y su hijo Ertugrul (m.1288) pasó a servir a los gobernantes seljúcidas de la zona, recibiendo a cambio las tierras de Senyud (en Frigia), entrando así en contacto directo con los bizantinos. Osmán, hijo de Ertugrul, fue nombrado Emir por Alaeddin III, sultán seljúcida de Icconium (Konya) y cuando el poder de los seljúcidas de Rum desapareció (1299), Osmán se convirtió en soberano independiente iniciando así la dinastía otomana, o de los turcos osmanlíes. Osmán (m. 1326) y sus descendientes no hicieron sino aumentar su territorio y consolidar su poder en Anatolia. Su hijo Orján (m.1359) conquistó Brussa, a la que convirtió en su capital, organizó la administración, creó moneda propia y reorganizó al ejército (creó el famoso cuerpo de jenízaros), en Brussa construyó un palacio cuya puerta principal se denominaba la Sublime Puerta, nombre que luego se dio al poder imperial otomano hasta su desaparición. -

Celalzade Mustafa Çeleb, Bureaucracy

“KOCA N İŞ ANCI” OF KANUN İ: CELALZADE MUSTAFA ÇELEB İ, BUREAUCRACY AND “KANUN” IN THE REIGN OF SULEYMAN THE MAGNIFICENT (1520–1566) A Ph.D. Dissertation by MEHMET ŞAK İR YILMAZ Department of History Bilkent University Ankara September 2006 To my family “KOCA N İŞ ANCI” OF KANUN İ: CELALZADE MUSTAFA ÇELEB İ, BUREAUCRACY AND “KANUN” IN THE REIGN OF SULEYMAN THE MAGNIFICENT (1520–1566) The Institute of Economics and Social Sciences of Bilkent University by MEHMET ŞAK İR YILMAZ In Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in THE DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY BİLKENT UNIVERSITY ANKARA September 2006 I certify that I have read this thesis and have found that it is fully adequate, in scope and in quality, as a thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History. --------------------------------- Prof. Dr. Halil İnalcık Supervisor I certify that I have read this thesis and have found that it is fully adequate, in scope and in quality, as a thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History. --------------------------------- Prof. Dr. Özer Ergenç Examining Committee Member I certify that I have read this thesis and have found that it is fully adequate, in scope and in quality, as a thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History. --------------------------------- Prof. Dr. Evgeni Radushev Examining Committee Member I certify that I have read this thesis and have found that it is fully adequate, in scope and in quality, as a thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History. --------------------------------- Asst. Prof. Hasan Ünal Examining Committee Member I certify that I have read this thesis and have found that it is fully adequate, in scope and in quality, as a thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History. -

A Study of Muslim Economic Thinking in the 11Th A.H. / 17Th C.E. Century

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Munich Personal RePEc Archive MPRA Munich Personal RePEc Archive A study of Muslim economic thinking in the 11th A.H. / 17th C.E. century Abdul Azim Islahi Islamic Economics Institute, King Abdulaziz University, Jeddah, KSA 2009 Online at https://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/75431/ MPRA Paper No. 75431, posted 6 December 2016 02:55 UTC Abdul Azim Islahi Islamic Economics Research Center King Abdulaziz University Scientific Publising Centre King Abdulaziz University P.O. Box 80200, Jeddah, 21589 Kingdom of Saudi Arabia FOREWORD There are numerous works on the history of Islamic economic thought. But almost all researches come to an end in 9th AH/15th CE century. We hardly find a reference to the economic ideas of Muslim scholars who lived in the 16th or 17th century, in works dealing with the history of Islamic economic thought. The period after the 9th/15th century remained largely unexplored. Dr. Islahi has ventured to investigate the periods after the 9th/15th century. He has already completed a study on Muslim economic thinking and institutions in the 10th/16th century (2009). In the mean time, he carried out the study on Muslim economic thinking during the 11th/17th century, which is now in your hand. As the author would like to note, it is only a sketch of the economic ideas in the period under study and a research initiative. It covers the sources available in Arabic, with a focus on the heartland of Islam. -

The Sokollu Family Clan and the Politics of Vizierial

Uroš Dakiü THE SOKOLLU FAMILY CLAN AND THE POLITICS OF VIZIERIAL HOUSEHOLDS IN THE SECOND HALF OF THE SIXTEENTH CENTURY MA Thesis in Comparative History, with the specialization in Interdisciplinary Medieval Studies. CEU eTD Collection Central European University Budapest May 2012 THE SOKOLLU FAMILY CLAN AND THE POLITICS OF VIZIERIAL HOUSEHOLDS IN THE SECOND HALF OF THE SIXTEENTH CENTURY by Uroš Dakiü (Serbia) Thesis submitted to the Department of Medieval Studies, Central European University, Budapest, in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the Master of Arts degree in Comparative History, with the specialization in Interdisciplinary Medieval Studies. Accepted in conformance with the standards of the CEU. ____________________________________________ Chair, Examination Committee ____________________________________________ Thesis Supervisor ____________________________________________ Examiner ____________________________________________ CEU eTD Collection Examiner Budapest May 2012 ii THE SOKOLLU FAMILY CLAN AND THE POLITICS OF VIZIERIAL HOUSEHOLDS IN THE SECOND HALF OF THE SIXTEENTH CENTURY by Uroš Dakiü (Serbia) Thesis submitted to the Department of Medieval Studies, Central European University, Budapest, in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the Master of Arts degree in Comparative History, with the specialization in Interdisciplinary Medieval Studies Accepted in conformance with the standards of the CEU. ____________________________________________ External Reader CEU eTD Collection Budapest May 2012 iii THE SOKOLLU -

Introduction on Being Osman

Introduction On Being Osman In 1688, in the tumultuous aft ermath of the failed Ottoman siege of Vienna, a Muslim soldier surrendered to the Habsburg army and became a prisoner of war. Young and from a well-connected family, he expected to be quickly ransomed and reunited with his loved ones. Instead, Osman of Timişoara would spend twelve long years in captiv- ity, fi nally regaining his freedom only aft er a daring cross-border escape that could easily have cost his life. By that time, although still a com- paratively young man, Osman had faced enough adversity to last many lifetimes: torture by a sadistic master, brutal confi nement in a dungeon, the hunger and contagion of an army camp in winter, and worse. But Osman persevered, and as the years of his captivity wore on, he man- aged gradually to improve his condition and even to win the esteem of his captors. Eventually, Osman became a household servant of one of the highest-ranking noblemen of Habsburg Vienna, a position of relative privilege from which a range of completely unforeseen opportunities were opened to him. Th rough his master’s patronage, he learned a most unexpected trade, apprenticing with a Parisian chef to become an expert pâtissier. In his master’s service, he traveled throughout the Habsburg realms and well beyond, even to distant lands in Germany and Italy barely known to his Ottoman contemporaries. Th anks to his master’s connections, he also became a man of infl uence among Vien- na’s many Ottoman Muslims, intervening on behalf of some of them both with the authorities and with their captors.