Celalzade Mustafa Çeleb, Bureaucracy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

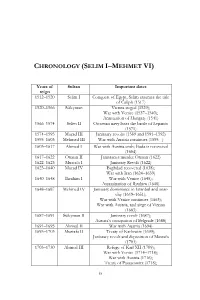

Selim I–Mehmet Vi)

CHRONOLOGY (SELIM I–MEHMET VI) Years of Sultan Important dates reign 1512–1520 Selim I Conquest of Egypt, Selim assumes the title of Caliph (1517) 1520–1566 Süleyman Vienna sieged (1529); War with Venice (1537–1540); Annexation of Hungary (1541) 1566–1574 Selim II Ottoman navy loses the battle of Lepanto (1571) 1574–1595 Murad III Janissary revolts (1589 and 1591–1592) 1595–1603 Mehmed III War with Austria continues (1595– ) 1603–1617 Ahmed I War with Austria ends; Buda is recovered (1604) 1617–1622 Osman II Janissaries murder Osman (1622) 1622–1623 Mustafa I Janissary Revolt (1622) 1623–1640 Murad IV Baghdad recovered (1638); War with Iran (1624–1639) 1640–1648 İbrahim I War with Venice (1645); Assassination of İbrahim (1648) 1648–1687 Mehmed IV Janissary dominance in Istanbul and anar- chy (1649–1651); War with Venice continues (1663); War with Austria, and siege of Vienna (1683) 1687–1691 Süleyman II Janissary revolt (1687); Austria’s occupation of Belgrade (1688) 1691–1695 Ahmed II War with Austria (1694) 1695–1703 Mustafa II Treaty of Karlowitz (1699); Janissary revolt and deposition of Mustafa (1703) 1703–1730 Ahmed III Refuge of Karl XII (1709); War with Venice (1714–1718); War with Austria (1716); Treaty of Passarowitz (1718); ix x REFORMING OTTOMAN GOVERNANCE Tulip Era (1718–1730) 1730–1754 Mahmud I War with Russia and Austria (1736–1759) 1754–1774 Mustafa III War with Russia (1768); Russian Fleet in the Aegean (1770); Inva- sion of the Crimea (1771) 1774–1789 Abdülhamid I Treaty of Küçük Kaynarca (1774); War with Russia (1787) -

Milli Mücadele Döneminde Mehmet Akif Ve Islamcilik*

Turkish Studies - International Periodical For The Languages, Literature and History of Turkish or Turkic Volume 9/12 Fall 2014, p. 563-572, ANKARA-TURKEY MİLLİ MÜCADELE DÖNEMİNDE MEHMET AKİF VE İSLAMCILIK* Emin OBA** Dinçer ÖZTÜRK** Hulisi GÜRBÜZ** ÖZET Mehmet Akif Ersoy edebi kişiliği, ahlakı ve yaşam tarzı ile örnek bir insan modelidir. İstiklal Marşı şairi olarak da bilinen Akif, Türk halkının gönlünde taht kurmuştur. Sadece Türkiye’deki Türklerin değil, diğer coğrafyalarda yaşayan Türklerinde gönlünü fethetmiş, sevgisini kazanmıştır. Çalışmamızda, Mehmet Akif’in İslamcılık fikirleri ve faaliyetleri hakkında bilgi verilmeye çalışılmıştır. Akif’in İslamcılık fikri için yaptıklarına değinilmiştir. Onun İslamcılık anlayışı ve beklentilerinin neler olduğu ve bu beklentileri gerçekleştirmek için yaptığı çalışmalar dikkate alınmıştır. Akif halkı, Asr-ı Saadet zamanındaki İslam yaşamı gibi, bir hayatın yaşanması gerektiği fikrini savunmuştur. Bunu vaazlarında dile getirmiştir. Burada Akif’in daha çok Anadolu’da verdiği vaazlara dikkat çekilmek istenmiştir (Kastamonu Nasrullah Camii Vaazı, Balıkesir Zağanos Paşa Camii Vaazı gibi). Mehmet Akif’in Milli Mücadele’deki faaliyetleri ve fikirleri verilmeye çalışılmıştır. Akif, Müslüman toplumların, Gayr-ı Müslim toplumların boyunduruğu altında yaşayamayacağı fikrini savunmuştur. Osmanlı devletinin yıkılma sürecine girmesinden dolayı, imparatorluğun bünyesinde yaşayan devletlerin kendi kaderinin tayin etmesi gerektiği fikrini savunarak, Milli Mücadeleye her alanda destek vermiştir. Bu doğrultuda Anadolu’nun çeşitli yerlerinde vaazlar vermiş, halkın milli mücadeleye destek vermelerini istemiştir. Ayrıca, çalışmamızda Akif’in Sebilü’r-reşad ve Sırat-ı Müstakim’deki konumu hakkında bilgilere de yer verilmiştir. Akif, bu mecmualar aracılığıyla Milli Mücadeleyi eserleriyle desteklemiştir. Akif’in siyasi yönü üzerinde de durulmuştur. O siyasetin her türlüsünden kaçınmıştır, daha ileri giderek siyaset kelimesinden bile uzak durmuştur. Siyasetten Allah’a sığınmıştır. -

Turkomans Between Two Empires

TURKOMANS BETWEEN TWO EMPIRES: THE ORIGINS OF THE QIZILBASH IDENTITY IN ANATOLIA (1447-1514) A Ph.D. Dissertation by RIZA YILDIRIM Department of History Bilkent University Ankara February 2008 To Sufis of Lāhijan TURKOMANS BETWEEN TWO EMPIRES: THE ORIGINS OF THE QIZILBASH IDENTITY IN ANATOLIA (1447-1514) The Institute of Economics and Social Sciences of Bilkent University by RIZA YILDIRIM In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in THE DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY BILKENT UNIVERSITY ANKARA February 2008 I certify that I have read this thesis and have found that it is fully adequate, in scope and in quality, as a thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History. …………………….. Assist. Prof. Oktay Özel Supervisor I certify that I have read this thesis and have found that it is fully adequate, in scope and in quality, as a thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History. …………………….. Prof. Dr. Halil Đnalcık Examining Committee Member I certify that I have read this thesis and have found that it is fully adequate, in scope and in quality, as a thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History. …………………….. Prof. Dr. Ahmet Yaşar Ocak Examining Committee Member I certify that I have read this thesis and have found that it is fully adequate, in scope and in quality, as a thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History. …………………….. Assist. Prof. Evgeni Radushev Examining Committee Member I certify that I have read this thesis and have found that it is fully adequate, in scope and in quality, as a thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History. -

Teşkilat Ve Đşleyiş Bakımından Doğu Hududundaki Osmanlı Kaleleri Ve

Teşkilat ve Đşleyiş Bakımından Doğu Hududundaki Osmanlı Kaleleri ve Mevâcib Defterleri The Ottoman Castles in Eastern Border of in Terms of Organization and Operation and Mevacib Defters Orhan Kılıç * Özet Bir çeşit askeri sayım niteliğinde olan mevâcib defterleri ulûfe sistemi içinde olan askeri sınıfların tespiti için en önemli arşiv kaynaklarıdır. Bu defterler sayesinde merkez ve merkez dışında görev yapan yevmiyyeli askerlerin mevcudunu, aldıkları ücretleri, isimlerini ve teşkilatlanmalarını tespit etmek mümkündür. Osmanlı coğrafyasının değişik bölgelerindeki hudut kaleleri, iç bölgelerdeki kalelere göre çok daha kalabalık ve askeri sınıfların çeşitliliği bakımından daha da zengin olmuştur. Bu kalelerde kadrolu askerlerinin yanı sıra merkezden görevlendirilen nöbetçi askerler de muhafaza hizmetinde bulunmuşlardır. Bu yapılanma, hudut kalelerinin bulunduğu şehirlerin adeta bir asker şehri görüntüsü vermesine sebep olmuştur. Anahtar Kelimeler: Osmanlı, Van, Erzurum, Yeniçeri, Mevâcib, Kale teşkilatı. Abstract Mevacib defters, a type of military counting, are the most important archive sources to determine the military corps in ulufe. Due to these defter, it is possible to identify the size, payments, names and organizations of the retained soldiers working in and out of center. Border castles in the different parts of the Ottoman geography were more crowded than the inland castles and richer according to the variety of military corps. In these castles, sentries assigned from the center gave maintenance service as well as permanent soldiers. This settlement made the cities in which these castles exist have an appearance of a military city. Keywords: Ottoman, Van, Erzurum, Mevâcib, Janissary, Castle organization. * Prof. Dr., Fırat Üniversitesi Đnsani ve Sosyal Bilimler Fakültesi Tarih Bölümü Elazığ/TÜRKĐYE. [email protected] 88 ORHAN KILIÇ Osmanlı askeri sistemi iki temel unsurun üzerine bina edilmişti. -

By Aijaz Ahmed

THESIS ISLAM IN MODERN TURKEY (1938-82) flBSTRflCT THESIS SUBMITTED FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF MLOSOPHY IN ISLAMIC STUDIES BY AIJAZ AHMED UNDER THE SUPERVISION OF DR. SAYYIDAHSAN READER DEPARTMiNT OF ISLAMIC STTUDISS ALI6ARH MUSLIM UNIVERSITY ALIGARH (INDIA) 20Di STff^o % ABSTRACT In tenth century, the Turks of central Asia had converted to Islam and by the eleventh century they began to push their way into South-Eastern Russia and Persia. The Ottoman State emerged consequent to an Islamic movement under Ghazi Osman (1299-1326), founder of the dynasty, at Eskisehir, in North- Eastern Anatolia. Sufis, Ulema and Ghazis of Anatolia played an important role in this movement. For six centuries the Ottomans were almost constantly at war with Christian Europe and had succeeded in imposing the Islamic rule over a large part of Europe. The later Sultans could not maintain it strictly. With the expansion of the Ottoman dominions the rulers became more autocratic with the sole aim of conquering alien land. To achieve this the rulers granted freedom and cultural autonomy to his non-Muslim subjects and allowed the major religious groups to establish self governing communities under the leadership of their own religious chiefs. The recent work is spread over two parts containing eight chapters with a brief introduction and my own conclusions. Each part has four chapters. Part I, chapters I to IV, deals with the political mobilization of the Turkish peasants from the beginning of the modernization period and to the war of Independence as well as the initial stages of the transition to comparative politics. -

Investigation of Structural and Architectural Properties of Historical Kastamonu Houses

IOSR Journal of Engineering (IOSRJEN) www.iosrjen.org ISSN (e): 2250-3021, ISSN (p): 2278-8719 Vol. 07, Issue 12 (December. 2017), ||V1|| PP 69-73 Investigation Of Structural And Architectural Properties Of Historical Kastamonu Houses Ahmet Gökdemir1,Can Demirel2 1(Gazi University Faculty of Technology Department of Civil Engineering,Ankara /Turkey) 2(Kırklareli University, Pınarhisar Vocational School, Construction Department, Kırklareli /Turkey) Corresponding Author: Can Demirel2 Abstract: The destruction and desolation of historical environment is important not only in the architectural terms but also in cultural and historical values. Kastamonu, the city rich in historical and cultural heritage, is one of the most important settlements of the traditional Turkish house and of the near-term Ottoman architecture. In this study, the architectural and structural features of the Historical Kastamonu Houses are examined and the causes of damage to houses are mentioned in the light of this information. Keywords: - Kastamonu Houses, architectural, historical, cultural. --------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- Date of Submission: 15-12-2017 Date of acceptance: 30-12-2017 --------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- I. INTRODUCTION Traditional Turkish houses have undergone major developments in time and in regions distinct in terms of climate, nature and culture, and this has brought different house types. On the other hand, all traditional houses are made up of certain cultural values. When the architectural design and details of traditional Turkish houses are examined, it is seen that all designs and solutions serve a certain purpose and have a certain benefit. In particular, the concept of privacy developed through the transition to settled life and acceptance of Islam; played an important role in the formation of traditional Turkish houses. -

Effect of Smell in Historical Environments

New Trends and Issues Proceedings on Humanities and Social Sciences Volume 4, Issue 11, (2017) 297-306 ISSN : 2547-881 www.prosoc.eu Selected Paper of 6th World Conference on Design and Arts (WCDA 2017), 29 June – 01 July 2017, University of Zagreb, Zagreb – Croatia. Effect of Smell in Historical Environments Nur Belkayali a*, Faculty of Engineering and Architecture, Kastamonu University, Kastamonu 37000, Turkey. Elif Ayan b, Faculty of Engineering and Architecture, Kastamonu University, Kastamonu 37000, Turkey. Suggested Citation: Belkayali, N. & Ayan, E. (2017). Effect of smell in historical environments. New Trends and Issues Proceedings on Humanities and Social Sciences. [Online]. 4(11), 297-306. Available from: www.prosoc.eu Selection and peer review under responsibility of Prof. Dr. Ayse Cakir Ilhan, Ankara University, Turkey. ©2017 SciencePark Research, Organization & Counseling. All rights reserved. Abstract Smell is an obscure composition in the space planning and design processes, while visual and audial aspects are more dominant. Smell has an important place in the preference of the place, is an important factor affecting people in terms of sociological, psychological and bioclimatic comforts, although it differs from person to person. In this study, the existence of natural and artificial smell sources in historical environments and the effect of the smell of the preference of these environments were investigated. The study was carried out in historical sites located in the urban site in the centre of Kastamonu province. The study emphasises that in the process of space planning and design, smell should be evaluated together with other senses. Also, attempts have been made to determine the contribution of the sources of smell to historical places, which has an important position for urban identity. -

THE JOURNAL of OTTOMAN .STUDIES Xx

OSMANLI ARAŞTIRMALARI xx Neşir Heyeti - Editorial Board Halil İNALerK-Nejat GÖYÜNÇ Heath W. LOWRY- İsmail ER ÜNSAL Klaus KREISER- A. Atilla ŞENTÜRK THE JOURNAL OF OTTOMAN .STUDIES xx İstanbul - 2000 Sahibi : ENDERUN KİTABEVİ adına İsmail ÖZDOGAN Tel: + 90 212 528 63 18 Fax :++- 90 212 528 63 17 Yazı İ ş l eri Sorumlusu : Nejat GÖYÜNÇ Tel : + 90 216 333 91 16 Basıldı ğ ı Yer : KİTAP MATBAACILIK San. ve Tic. Ltd. Şti . Tel: + 90 212 567 48 84 Cilt: FATiH MÜCELLiT Matbaacılık ve Ambalaj San. ve Tic. Ltd. Şti. Tel : + 90 501 28 23 - 61 2 86 71 Yaz ı şma Adresi: ENDERUN Kİ TABEVİ, BüyUk Reşitpaşa Cad. Yümni İş Merkezi 22/46 Rt!yaz ıı - istanbul THE LİFE OF KÖPRÜLÜZADE FAZIL MUSTAFA PASHA AND HIS REFORMS (1637-1691) Fehmi YILMAZ His life before his vizierate The Köprülüs are known as an eminent vizier family in the Ottoman state due to their reforming initiatives especially when the state encountered serious internal and external problems in the second half of the seventeenth century. The name of Köprülü comes from the town of Köprü Iocated near Amasya. Köprülü Mehmed Pasha, who gave his name to the family, was brought to İstanbul from Albania as a devshirme recruit when he was a child, and he was trained in the Acemi Oglanlar Odjagı of the pala:ce. He spent a significant period of his youthin the palace. He was appointed as hassa cook in the Matbah-ı Amire in 1623. He also joined the retinue of Boshnak Hüsrev Pas ha who was employed in the same period·in the Has-Oda and who would later become a grand vizier. -

Rebellion, Janissaries and Religion in Sultanic Legitimisation in the Ottoman Empire

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Istanbul Bilgi University Library Open Access “THE FURIOUS DOGS OF HELL”: REBELLION, JANISSARIES AND RELIGION IN SULTANIC LEGITIMISATION IN THE OTTOMAN EMPIRE UMUT DENİZ KIRCA 107671006 İSTANBUL BİLGİ ÜNİVERSİTESİ SOSYAL BİLİMLER ENSTİTÜSÜ TARİH YÜKSEK LİSANS PROGRAMI PROF. DR. SURAIYA FAROQHI 2010 “The Furious Dogs of Hell”: Rebellion, Janissaries and Religion in Sultanic Legitimisation in the Ottoman Empire Umut Deniz Kırca 107671006 Prof. Dr. Suraiya Faroqhi Yard. Doç Dr. M. Erdem Kabadayı Yard. Doç Dr. Meltem Toksöz Tezin Onaylandığı Tarih : 20.09.2010 Toplam Sayfa Sayısı: 139 Anahtar Kelimeler (Türkçe) Anahtar Kelimeler (İngilizce) 1) İsyan 1) Rebellion 2) Meşruiyet 2) Legitimisation 3) Yeniçeriler 3) The Janissaries 4) Din 4) Religion 5) Güç Mücadelesi 5) Power Struggle Sosyal Bilimler Enstitüsü’nde Tarih Yüksek Lisans derecesi için Umut Deniz Kırca tarafından Mayıs 2010’da teslim edilen tezin özeti. Başlık: “Cehennemin Azgın Köpekleri”: Osmanlı İmparatorluğu’nda İsyan, Yeniçeriler, Din ve Meşruiyet Bu çalışma, on sekizinci yüzyıldan ocağın kaldırılmasına kadar uzanan sürede patlak veren yeniçeri isyanlarının teknik aşamalarını irdelemektedir. Ayrıca, isyancılarla saray arasındaki meşruiyet mücadelesi, çalışmamızın bir diğer konu başlığıdır. Başkentte patlak veren dört büyük isyan bir arada değerlendirilerek, Osmanlı isyanlarının karakteristik özelliklerine ve isyanlarda izlenilen meşruiyet pratiklerine ışık tutulması hedeflenmiştir. Çalışmamızda kullandığımız metot dâhilinde, 1703, 1730, 1807 ve 1826 isyanlarını konu alan yazma eserler karşılaştırılmış, müelliflerin, eserlerini oluşturdukları süreçteki niyetleri ve getirmiş oldukları yorumlara odaklanılmıştır. Argümanların devamlılığını gözlemlemek için, 1703 ve 1730 isyanları ile 1807 ve 1826 isyanları iki ayrı grupta incelenmiştir. 1703 ve 1730 isyanlarının ortak noktası, isyancıların kendi çıkarları doğrultusunda padişaha yakın olan ve rakiplerini bu sayede eleyen politik kişilikleri hedef almalarıdır. -

A Comparison of Mehmet Akif Ersoy and Ziya Gökalp

ISLAMIST AND TURKIST CONCEPTUALIZATION OF NATION IN THE LATE OTTOMAN PERIOD: A COMPARISON OF MEHMET AKİF ERSOY AND ZİYA GÖKALP A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE INSTITUTE OF SOCIAL SCIENCES OF ANKARA YILDIRIM BEYAZIT UNIVERSITY BY KEMAL UFUK IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF INTERNATIONAL RELATIONS IN THE DEPARTMENT OF INTERNATIONAL RELATIONS JUNE 2019 Approval of the Institute of Social Sciences: __________________________________ Doç. Dr. Seyfullah YILDIRIM Manager of Institute I certify that this thesis satisfies all the requirements as a thesis for the degree of Master of Science. ____________________________________ Prof. Dr. Birol AKGÜN Head of Department This is to certify that we have read this thesis and that in our opinion it is fully adequate, in scope and quality, as a thesis for the degree of Master of Science. _____________________________________ Asst. Prof. Dr. Bayram SİNKAYA Supervisor Examining Committee Members Assoc. Prof. Dr. Mustafa Serdar PALABIYIK (TOBB ETU, PSIR)__________________ Asst. Prof. Dr. Bayram SİNKAYA (AYBU, IR) __________________ Asst. Prof. Dr. Güliz DİNÇ (AYBU, PSPA) __________________ ii I hereby declare that all information in this thesis has been obtained and presented in accordance with academic rules and ethical conduct. I also declare that, as required by these rules and conduct, I have fully cited and referenced all material and results that are not original to this work; otherwise I accept all legal responsibility. Name, Last name : Kemal UFUK Signature : iii ABSTRACT ISLAMIST AND TURKIST CONCEPTUALIZATION OF NATION IN THE LATE OTTOMAN PERIOD: A COMPARISON OF MEHMET AKİF ERSOY AND ZİYA GÖKALP UFUK, Kemal M.A., Department of International Relations Supervisor: Asst. -

Resources for the Study of Islamic Architecture Historical Section

RESOURCES FOR THE STUDY OF ISLAMIC ARCHITECTURE HISTORICAL SECTION Prepared by: Sabri Jarrar András Riedlmayer Jeffrey B. Spurr © 1994 AGA KHAN PROGRAM FOR ISLAMIC ARCHITECTURE RESOURCES FOR THE STUDY OF ISLAMIC ARCHITECTURE HISTORICAL SECTION BIBLIOGRAPHIC COMPONENT Historical Section, Bibliographic Component Reference Books BASIC REFERENCE TOOLS FOR THE HISTORY OF ISLAMIC ART AND ARCHITECTURE This list covers bibliographies, periodical indexes and other basic research tools; also included is a selection of monographs and surveys of architecture, with an emphasis on recent and well-illustrated works published after 1980. For an annotated guide to the most important such works published prior to that date, see Terry Allen, Islamic Architecture: An Introductory Bibliography. Cambridge, Mass., 1979 (available in photocopy from the Aga Khan Program at Harvard). For more comprehensive listings, see Creswell's Bibliography and its supplements, as well as the following subject bibliographies. GENERAL BIBLIOGRAPHIES AND PERIODICAL INDEXES Creswell, K. A. C. A Bibliography of the Architecture, Arts, and Crafts of Islam to 1st Jan. 1960 Cairo, 1961; reprt. 1978. /the largest and most comprehensive compilation of books and articles on all aspects of Islamic art and architecture (except numismatics- for titles on Islamic coins and medals see: L.A. Mayer, Bibliography of Moslem Numismatics and the periodical Numismatic Literature). Intelligently organized; incl. detailed annotations, e.g. listing buildings and objects illustrated in each of the works cited. Supplements: [1st]: 1961-1972 (Cairo, 1973); [2nd]: 1972-1980, with omissions from previous years (Cairo, 1984)./ Islamic Architecture: An Introductory Bibliography, ed. Terry Allen. Cambridge, Mass., 1979. /a selective and intelligently organized general overview of the literature to that date, with detailed and often critical annotations./ Index Islamicus 1665-1905, ed. -

Contextualizing an 18 Century Ottoman Elite: Şerđf Halđl Paşa of Şumnu and His Patronage

CONTEXTUALIZING AN 18TH CENTURY OTTOMAN ELITE: ŞERĐF HALĐL PAŞA OF ŞUMNU AND HIS PATRONAGE by AHMET BĐLALOĞLU Submitted to the Graduate School of Arts and Social Sciences in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in History Sabancı University 2011 CONTEXTUALIZING AN 18TH CENTURY OTTOMAN ELITE: ŞERĐF HALĐL PAŞA OF ŞUMNU AND HIS PATRONAGE APPROVED BY: Assoc. Prof. Dr. Tülay Artan …………………………. (Dissertation Supervisor) Assist. Prof. Dr. Hülya Adak …………………………. Assoc. Prof. Dr. Bratislav Pantelic …………………………. DATE OF APPROVAL: 8 SEPTEMBER 2011 © Ahmet Bilaloğlu, 2011 All rights Reserved ABSTRACT CONTEXTUALIZING AN 18 TH CENTURY OTTOMAN ELITE: ŞERĐF HALĐL PAŞA OF ŞUMNU AND HIS PATRONAGE Ahmet Bilaloğlu History, MA Thesis, 2011 Thesis Supervisor: Tülay Artan Keywords: Şumnu, Şerif Halil Paşa, Tombul Mosque, Şumnu library. The fundamental aim of this thesis is to present the career of Şerif Halil Paşa of Şumnu who has only been mentioned in scholarly research due to the socio-religious complex that he commissioned in his hometown. Furthermore, it is aimed to portray Şerif Halil within a larger circle of elites and their common interests in the first half of the 18 th century. For the study, various chronicles, archival records and biographical dictionaries have been used as primary sources. The vakıfnâme of the socio-religious complex of Şerif Halil proved to be a rare example which included some valuable biographical facts about the patron. Apart from the official posts that Şerif Halil Paşa occupied in the Defterhâne and the Divânhâne , this study attempts to render his patronage of architecture as well as his intellectual interests such as calligraphy and literature.