Mega Transport Project Financing in Sweden and Denmark – Does Financing Outside the Normal Channels Have Sustainability Implications?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Property and Citizenship in Developing Societies

1st Conference of the Procit Research Network Property and Citizenship in Developing Societies 28-31 May 2013, Copenhagen www.procit.dk www.eilenberg.dk Cover Image: Jakarta slums Photo by Michael Eilenberg University of Aarhus, Denmark Property and Citizenship in Developing Societies Conference 28-31 May 2013 Copenhagen PROGRAM AND ABSTRACTS ORGANIZING COMMITTEE Prof. Christian Lund, University of Copenhagen Prof. Michael Eilenberg, University of Aarhus Ms. Christine Svop, University of Aarhus PROPERTY AND CITIZENSHIP IN DEVELOPING SOCIETIES No single political institution controls space. Neither in recent democracies nor in one-party regimes, or in post-conflict societies, do governments actually wield the control they aspire to exercise. Therefore, people protect their claims by whatever means available in order to solidify access and secure exclusion of others. Actors address different institutions to have claims validated, and they will fashion their claims to land according to the nature of the institution. Conversely, however, political institutions will attempt to validate certain claims as rights and thus attempt to establish political authority – and sovereignty. The production of property rights in varied forms and the intertwined production of political subjects results in the inclusion and exclusion of people. We invite papers that analyse the assemblages of governing powers and investigate the institutional dynamics of recognition and exclusion and what institutions become the results of these processes? In particular we welcome papers that deal with connections between access to land and resources, and political identity and subjectivity. In this lies a profound question about state formation. The papers can engage with these questions in rural, peri-urban and urban settings alike. -

Tetra Smoothes Efficient Operations for Movia's Transportation Routes In

CASE STUDY TETRA takes control of transport - by sea, by land Greater Copenhagen and Sealand Region – Denmark. Customer Profile Denmark’s capital, Copenhagen, houses the Royal Family, the Company Danish Parliament, and a number of government and financial Movia Public Transport institutions, as well as international organisations and company Industry Name headquarters. In recent years, economic activity levels have Transportation increased significantly and, with the opening of a rail & road Product Name • Dimetra IP TETRA system bridge between Copenhagen and Malmö (Sweden), the city • MTM700s with Vehicle has become a gateway to Scandinavia and the Baltic Area. Integrated Units Furthermore, the Copenhagen Airport serves as the main airport • MTH800 Hand-portables in northern Europe/Scandinavia. Solution Features • Dimetra IP provides high performance The city boasts a well-developed public transport network in terms • Highly resilient network solution of local trains, metro lines and buses. But increasing traffic levels in • Fast, reliable call set up recent years have led to congestion, which has renewed the focus • GPS Location Service on improving both traffic controls and public transport. Benefits • Voice & text radio communications Regional restructuring creates new communication challenges for Denmark’s largest • Centralised traffic monitoring transport authority. & control Movia Public Transport was formed in 2007, with the merger of HUR Trafik and two local county • Improved business efficiency transit agencies – VT and STS. This was in response to major municipal restructuring undertaken & SLAs by the Danish Government some five years earlier. • Increased passenger satisfaction Today, Movia is Denmark’s largest public transport agency, serving approximately 220 million passengers a year. It covers a population of some 2.4 million in Denmark’s Capital Region (with the exception of Bornholm), including Greater Copenhagen and the rest of the Sealand Region. -

Precedent Study

Smarter Travel in Six European Cities A Precedent Study Kay Cullinane BEng MIEI Research Masters Student of Civil Engineering at the University of Limerick Tom Cosgrove FIEI FIStructE Professor of Civil Engineering at the University of Limerick Smarter Travel European Precedent Study April 2010 Information contained in this report may be freely used provided the source is fully acknowledged Smarter Travel European Precedent Study April 2010 Table of contents 1.0 INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................ 1 2.0 MALMÖ ........................................................................................................................ 3 3.0 COPENHAGEN ............................................................................................................... 11 4.0 ODENSE ....................................................................................................................... 17 5.0 GRONINGEN ................................................................................................................. 24 6.0 DELFT ......................................................................................................................... 31 7.0 FREIBURG ..................................................................................................................... 35 8.0 REFERENCES ................................................................................................................. 39 Smarter Travel European Precedent Study -

Copenhagen Proposal to Host

Copenhagen proposal to host International Conference on Theorem Proving ITP 2011 ITP 2011 Table of Contents 1. Application .............................................................................................. 3 1.1. Associate Professor Carsten Schürmann and Associate Professor Joseph Roland Kiniry .................................................................................................. 4 2. Invitations ............................................................................................... 6 2.1. IT University of Copenhagen ........................................................................ 7 2.2. Lord Mayor, City of Copenhagen................................................................... 8 2.3. Wonderful Copenhagen, CVB ....................................................................... 9 3. Local Organisation ................................................................................. 10 3.1. The Organisers and Conference committee ................................................... 11 3.2. Tentative Conference Schedule ................................................................... 13 3.3. Public Relations and Outreach ..................................................................... 14 4. Why Copenhagen ................................................................................... 15 4.1. Copenhagen - The Greenest City in Europe ................................................... 16 4.2. ICT in Scandinavia ................................................................................... -

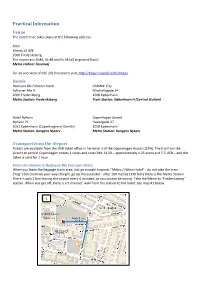

Practical Information Venue the Conference Takes Place at the Following Address

Practical Information Venue The conference takes place at the following address: Kilen Kilevej 14 A/B 2000 Frederiksberg The rooms are: Ks43, Ks.48 and Ks.54 (all at ground floor) Metro station: Fasanvej For an overview of ICIC 2010 locations visit, http://tinyurl.com/icic2010maps Hotels Radisson Blu Falconer Hotel CABINN City Falkoner Alle 9 Mitchellsgade 14 2000 Frederikberg 1568 København Metro Station: Frederiksberg Train Station: København H (Central Station) Hotel Nyhavn Copenhagen Strand Nyhavn 71 Havnegade 37 1051 København (Copenhagen in Danish) 1058 København Metro Station: Kongens Nytorv Metro Station: Kongens Nytorv Transport from the Airport Tickets are available from the DSB ticket office in Terminal 3 of the Copenhagen Airport (CPH). The trip from the airport to central Copenhagen covers 3 zones and costs DKK 31.50 – approximately 4.25 euros and 5.5 USD – and the ticket is valid for 1 hour. From the Airport to Radisson Blu Falconer Hotel: When you leave the baggage claim area, just go straight towards "Metro / Hilton Hotel" - do not take the train ("tog") but continue your way straight, go up the escalator - after 100 metres (330 feet) there is the Metro Station. There is only 1 line leaving the airport every 4 minutes, so you cannot be wrong. Take the Metro to “Frederiksberg” station. When you get off, there is a 5 minutes’ walk from the station to the hotel. See map #1 below. 1 From the Airport to Hotel Nyhavn and Copenhagen Strand: When you leave the baggage claim area, just go straight towards "Metro / Hilton Hotel" - do not take the train ("tog") but continue your way straight, go up the escalator - after 100 m there is the Metro. -

Light Rail Project in Copenhagen the Ring 2½ Corridor

Downloaded from orbit.dtu.dk on: Oct 05, 2021 Light rail project in Copenhagen the Ring 2½ corridor Andersen, Jonas Lohmann Elkjær; Landex, Alex; Nielsen, Otto Anker Published in: Trafikdage 2006 Publication date: 2006 Document Version Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Link back to DTU Orbit Citation (APA): Andersen, J. L. E., Landex, A., & Nielsen, O. A. (2006). Light rail project in Copenhagen: the Ring 2½ corridor. In Trafikdage 2006 General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Light rail project in Copenhagen – the Ring 2½ corridor Jonas L.E. Andersen, Research Assistant, M.Sc., [email protected] Alex Landex, Research Assistant, M.Sc., [email protected] Otto Anker Nielsen, Professor, [email protected] Centre for Traffic and Transport (CTT), Technical University of Denmark (DTU) Bygning 115, st.tv. Bygningstorvet, 2800 Kgs. Lyngby 1. Abstract The need for high class public transport service of the increasing travel across the radial urban structure of the greater Copenhagen region was examined through planning of a light rail. -

Velkommen Til København! Welcome to Copenhagen!

Velkommen til København! Welcome to Copenhagen! Online Vacation Center welcomes you to Copenhagen and wishes you a pleasant stay! One of the oldest capital cities in Europe and home to the oldest European Monarchy, Copenhagen is considered the crown jewel of Scandinavia. With its rich history, modern approach to life, stunning architecture and thriving culinary scene, Copenhagen is a truly unique city. In this guide you will find useful information about the city; however, we encourage you to speak with the concierge for more detailed information. We also recommend keeping a business card from the hotel in your wallet or taking a picture of it, so that you always have the hotel address with you. Online Vacation Center is interested in your feedback, so we encourage you to fill out our post-vacation survey when you get home. Every comment is read by management, and some great additions to our programs have been suggested by clients like you. Have a wonderful stay in Copenhagen! THINGS TO DO AND SEE Strøget - One of the longest pedestrian streets in Europe with an array of cafés and boutiques. Many stores are closed on Sunday. Nyhavn - A picturesque 17th-century canal with colorful houses along the waterfront. National Museum of Denmark (Nationalmuseet) - Contains fascinating exhibits that focuses on 14,000 years of Danish history and cultural exhibits from around the world. Closed on Mondays. For information, visit https://en.natmus.dk/ The Little Mermaid Statue (Den Lille Havfrue) - The world-famous statue based on Hans Christian Anderson’s fairy tale. Bus 26 stops close to the statue, or take the water ferry from Nyhavn to the Nordre Toldbod ferry stop and walk 10 minutes from there. -

2. Local Transport Plans and Visions There Are Five Main Plans/Visions

2. Local Plans and Visions transport There are five main plans/visions setting goals for transport planning and actions: The Transport and Environmental Plan 2004: The overriding objective is to assure a fully functional transportation system for the city causing substantially less environmental impact than today. The plan contains an action plan on 20 initiatives. Copenhagen’s Cycle Politic 2002-2012 is the first overall action plan for the cycle conditions in the city. More cyclists, safety, speed, comfort are some of the subjects in focus. Eco-metropolis 2007: Has 4 themes and 13 measurable goals. One of the themes is Copenhagen as the World’s Best City for Cyclists. Especially important for transport is the objective saying “50 % of all people going to work or education in Copenhagen will go by bike”. CopenhagenClimate Plan 2009 contains 15 initiatives for transport and the goal is to reduce CO2-emissions from transport by 10 % from 2005 to 2015. The lighthouse initiative is electric and hydrogen cars running on wind energy. Municipal Strategy 2009: The overall objective for the modal split in Copenhagen is that for all trips ”on wheels” at least 1/3 must be by public transport, at least 1/3 by cycle and less than 1/3 by car. The key efforts of the plans for transport are The City of Cyclists Improved public transport Traffic calming and parking restrictions Environmental efforts like low emission zones, possible congestion charging and environmentally friendly vehicles The City of Cyclists The City of Copenhagen has set itself the overall goal to be the world’s best city for cyclists, and since 2007 this has set the framework for measures in the cyclist area. -

Supporting Electric Vehicles in Freight Transport in Copenhagen Municipality

Supporting electric vehicles in freight transport in Copenhagen Municipality Association of Danish Transport and Logistics Centres Hanna Baster Kent Bentzen Lars Bentzen Michael Stie Laugesen July 2014 2 I. DESCRIPTION OF URBAN FREIGHT TRAFFIC SITUATION IN COPENHAGEN MUNICIPALITY 9 1. Overall traffic and emission situation in Copenhagen Municipality 9 2. Problems/challenges identified within the urban freight transport activities performed in Copenhagen Municipality 14 3. Status of E-mobility in Copenhagen Municipality 17 II. GOALS 20 III. DEFINITION OF THE REQUIRED CONDITIONS FOR DEPLOYING DELIVERY ELECTRIC VEHICLES 23 1. Problems identified 23 2. Conditions required to enable green image becoming profitable 25 IV. SUMMARY OF FINDINGS (SECTION I-III) 27 V. RECOMMENDATIONS FOR SUPPORTING THE DEPLOYMENT OF ELECTRIC DELIVERY VEHICLES IN COPENHAGEN MUNICIPALITY 29 1. Regulatory tools 30 2. Cooperation between stakeholders 33 3. Promotion 35 4. Financial support tools 38 5. Logistic chain optimization 39 VI. RECOMMENDATION 45 REFERENCES 47 FOOTNOTES 49 3 List of figues Figure 1 Estimation of composition of cost of pollution generated daily ................................. 12 Figure 2 CO2 emission goals for energy production in 2025 in Copenhagen Municipality ..... 13 Figure 3 CPH Climate Plan: Role of alternatively fuelled vehicles in achieving CO2 goals. .. 20 Figure 4 Level of air pollutants produced by different types ................................................... 22 Figure 5 Cost of different alternative fuels (DKK/km). ........................................................... -

Arrival Instructions Dear Student, We Are Pleased to Welcome You to The

Arrival Instructions Dear student, We are pleased to welcome you to the Doctoral Colloquium, which will be hosted by Copenhagen Business School, Denmark from May 30 – June 1st 2010. We hope the following information will be of help during the Conference and make your stay in Copenhagen more enjoyable. Arrival in Copenhagen and transport Airport Copenhagen is the main hub for all air travel in this region of Northern Europe. Its stunning international airport (Kastrup) is eight kilometres southeast of the city. From the airport it takes just 14 minutes to reach the city centre by train or Metro, and 20 minutes to reach Copenhagen Business School (line M2 to CBS by the Metro). Regional trains and taxis are also available. The Metro station is located at the end of Terminal 3. Metro trains depart every 4 to 6 minutes during the day and every 15 minutes in the evening. The Metro operates from 5:00 in the morning until midnight from Monday to Wednesday, and around the clock Thursday to Sunday. Tickets are available at the Metro station and at the DBS ticket counter in Terminal 3. Regional trains also connect the airport with the Nørreport train/Metro station and the Central Railway Station. The train station is at Terminal 3. Tickets are available at the DBS office in Terminal 3 and in the station area. Taxis are plentiful. The fare includes VAT and a service charge. If you want to pay by credit card, inform the driver before the start of the journey. More information on getting to and from the airport . -

Copenhagen's Green Economy

Copenhagen Green Economy Leader Report A report by the Economics of Green Cities Programme at the London School of Economics and Political Science. Research Directors Graham Floater Director of Seneca and Principal Research Fellow, London School of Economics and Political Science Philipp Rode Executive Director of LSE Cities and Senior Research Fellow, London School of Economics and Political Science Dimitri Zenghelis Principal Research Fellow, Grantham Research Institute, London School of Economics and Political Science London School of Economics and Political Science Research Team Houghton Street London Matthew Ulterino WC2A 2AE Researcher, LSE Cities UK Duncan Smith Research Officer, LSE Cities Tel: +44 (0)20 7405 7686 Karl Baker Researcher, LSE Cities Catarina Heeckt Researcher, LSE Cities Advisors Nicky Gavron Greater London Authority Production and Graphic Design Atelier Works www.atelierworks.co.uk The full report is available for download from: http:// www.kk.dk/da/om-kommunen/indsatsomraader-og- politikker/natur-miljoe-og-affald/klima/co2-neutral- hovedstad This Report is intended as a basis for discussion. While every effort has been made to ensure the accuracy of the material in this report, the authors and/or LSE Cities will not be liable for any loss or damage incurred through the use of this report. Published by LSE Cities, London School of Economics and Political Science, 2014. Research support for this project was provided by Seneca Consultants SPRL. Cover photo credit: [email protected] Contents Executive Summary 7 -

ÖRESUND METRO COPENHAGEN MALMÖ 2017 This Report Has Been Compiled by the Municipality of Copenhagen and City of Malmö

COPENHAGEN MALMÖ ÖRESUND METRO CONNECTS GREATER COPENHAGEN RESULTS OF PHASE 3 – PRELIMINARY STUDY ÖRESUND METRO COPENHAGEN MALMÖ 2017 This report has been compiled by the Municipality of Copenhagen and City of Malmö. STEERING GROUP Bo Andersson, Chair of the City of Malmö Søren Tegen Pedersen, Deputy Chair of the Municipality of Copenhagen STEERING GROUP AFFILIATES City of Malmö: Christer Larsson, Jan-Inge Ahlfridh, Jan Haak, Johan Emanuelson PROJECT MANAGEMENT City of Malmö: Malena Möller, Klas Nydahl Municipality of Copenhagen: Jeppe Grønholt-Pedersen, Jarl Zinn EXTERNAL CONSULTANTS Rambøll, Metroselskabet, Trailc, Ehrenberg Kommunikation PHOTOS AND ILLUSTRATIONS Metroselskabet, Øresunds Brokonsortiet, Rambøll Palludan Fremtid, Malmö Arena, City of Malmö and Municipality of Copenhagen, Cees van Roeden, Jakob Boserup, Pierre Mens LAYOUT KK Design Copenhagen/Malmö, 2017 ÖRESUND METRO COPENHAGEN MALMÖ ÖRESUND METRO CONNECTS GREATER COPENHAGEN - RESULTS OF PHASE 3 – PRELIMINARY STUDY CONTENTS 3 Phases 1 and 2 (2012–2015) 4 Introduction Phase 3 5 The joint challenge 6 The Öresund metro expands the functional labour market and creates space for growth 7 The Öresund metro connects cities 9 The Öresund metro creates links to high-speed trains 10 Capital expenditure and technical conditions 11 Knowledge of the Öresund metro and its significance and effects 12 The continued work ABOUT THE ÖRESUND METRO PROJECT An Öresund metro between Copenhagen and Malmö is the vision for a metro line below Öresund with departures every 1½ minutes and a travel duration of approximately 20 minutes. It is a long-term and sustainable life- line that can bring the region’s two largest cities and Greater Copenhagen closer to each other and create greater accessibility and stronger cohesion.