Faith-Based Mediation?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

State Visit of H.E. Paul BIYA, President of the Republic of Cameroon, to Italy 20 - 22 March 2017

TRAVAIL WORK FATHERLANDPATRIE PAIX REPUBLIQUEDU CAMEROUN PEACE REPUBLIQUE OF CAMEROON Paix - Travail - Patrie Peace - Work- Fatherland ------- ------- CABINET CIVIL CABINET CIVIL ------- ------- R E CELLULE DE COMMUNICATION R COMMUNICATION UNIT P N U EP N U B UB OO L LIC O MER O IQ F CA ER UE DU CAM State Visit of H.E. Paul BIYA, President of the Republic of Cameroon, to Italy 20 - 22 March 2017 PRESS KIT Our Website : www.prc.cm TRAVAIL WORK FATHERLANDPATRIE PAIX REPUBLIQUEDU CAMEROUN PEACE REPUBLIQUE OF CAMEROON Paix - Travail - Patrie Peace - Work- Fatherland ------- ------- CABINET CIVIL CABINET CIVIL R ------- E ------- P RE N U P N U B UB OO L LIC O MER O IQ F CA ER CELLULE DE COMMUNICATION UE DU CAM COMMUNICATION UNIT THE CAMEROONIAN COMMUNITY IN ITALY - It is estimated at about 12,000 people including approximately 4.000 students. - The Cameroonian students’ community is the first African community and the fifth worldwide. - Fields of study or of specialization are: medicine (about 2800); engineering (about 400); architecture (about 300); pharmacy (about 150) and economics (about 120). - Some Cameroonian students receive training in hotel management, law, communication and international cooperation. - Cameroonian workers in Italy are about 300 in number. They consist essentially of former students practicing as doctors, pharmacists, lawyers or business executives. - Other Cameroonians with precarious or irregular status operate in small jobs: labourers, domestic workers, mechanics, etc. The number is estimated at about 1.500. 1 TRAVAIL WORK FATHERLANDPATRIE REPUBLIQUEDU CAMEROUN PAIX REPUBLIQUE OF CAMEROON PEACE Paix - Travail - Patrie Peace - Work- Fatherland ------- ------- CABINET CIVIL CABINET CIVIL ------- ------- R E ELLULE DE COMMUNICATION R C P E N COMMUNICATION UNIT U P N U B UB OO L LIC O MER O IQ F CA ER UE DU CAM GENERAL PRESENTATION OF CAMEROON ameroon, officially the Republic of Cameroon is History a country in the west Central Africa region. -

The Kosovo Report

THE KOSOVO REPORT CONFLICT v INTERNATIONAL RESPONSE v LESSONS LEARNED v THE INDEPENDENT INTERNATIONAL COMMISSION ON KOSOVO 1 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS Great Clarendon Street, Oxford ox2 6dp Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford Executive Summary • 1 It furthers the University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, Address by former President Nelson Mandela • 14 and education by publishing worldwide in Oxford New York Map of Kosovo • 18 Athens Auckland Bangkok Bogotá Buenos Aires Calcutta Introduction • 19 Cape Town Chennai Dar es Salaam Delhi Florence Hong Kong Istanbul Karachi Kuala Lumpur Madrid Melbourne Mexico City Mumbai Nairobi Paris São Paulo Singapore Taipei Tokyo Toronto Warsaw PART I: WHAT HAPPENED? with associated companies in Berlin Ibadan Preface • 29 Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the uk and in certain other countries 1. The Origins of the Kosovo Crisis • 33 Published in the United States 2. Internal Armed Conflict: February 1998–March 1999 •67 by Oxford University Press Inc., New York 3. International War Supervenes: March 1999–June 1999 • 85 © Oxford University Press 2000 4. Kosovo under United Nations Rule • 99 The moral rights of the author have been asserted Database right Oxford University Press (maker) PART II: ANALYSIS First published 2000 5. The Diplomatic Dimension • 131 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, 6. International Law and Humanitarian Intervention • 163 without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, 7. Humanitarian Organizations and the Role of Media • 201 or as expressly permitted by law, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reprographics rights organisation. -

Rapporto Sulla Politica Estera Italiana: Il Governo Renzi

Quaderni IAI RAPPORTO SULLA POLITICA ESTERA ITALIANA: IL GOVERNO RENZI Edizione 2016 a cura di Ettore Greco e Natalino Ronzitti Edizioni Nuova Cultura Questa pubblicazione è frutto della partnership strategica tra l’Istituto Affari Internazionali (IAI) e la Compagnia di San Paolo. Quaderni IAI Direzione: Natalino Ronzitti La redazione di questo volume è stata curata da Sandra Passariello Prima edizione luglio 2016 – Edizioni Nuova Cultura Per Istituto Affari Internazionali (IAI) Via Angelo Brunetti 9 - I-00186 Roma www.iai.it Copyright © 2016 Edizioni Nuova Cultura - Roma ISBN: 9788868127138 Copertina: Luca Mozzicarelli È vietata la riproduzione non autorizzata, anche parziale, realizzata con qualsiasiComposizione mezzo, grafica: compresa Luca la Mozzicarelli fotocopia, anche ad uso interno o didattico. Indice Lista degli Autori .............................................................................................................................................7 Lista degli acronimi ........................................................................................................................................9 1. Le scelte in Europa ................................................................................................................................. 11 1.1 Ruolo e posizioni in Europa, di Ettore Greco .....................................................................13 1.2 L’agenda economica dell’Unione europea, di Ferdinando Nelli Feroci .......................21 1.3 La governance economica europea, di Fabrizio -

The Society for the Propagation of the Faith National Director’S Message Mission Today Message Summer 2014

Vol. 72, No. 3 Summer 2014 Church building in India Pilgrimage in Papua New Guinea: “In the footsteps of the missionaries” Christians in the Holy Land: An update And more… The Society for the Propagation of the Faith National Director’s Message Mission Today Message Summer 2014 For most of us, winter has essential for believing in God. Not for believing that God exist, passed and spring is in the but for believing that God is love, merciful and faithful.”(Vatican air. The weather is changing, City April 27, 2014-Zenit.org) plants and flower are bloom- ing. It is that in between time We know how real the suffering of so many people of faith is, yet of year. Perhaps, like me, you this very suffering underlines the radiant hope of the Risen Lord. are working on your new year’s Our Pontifical Mission Societies deal with these same realities. goals while anticipating goals to You, in your prayers and support for the works of the Societies achieve prior to Summer arriv- are truly bearers of Good News. As we head into the summer ing. Maybe you too are begin- months, let us remember to keep the work of evangelization in ning to plan summer activities our prayers and in our actions too. and vacations. Spring brings a sense of renewal and change. God bless you. Looking at the fearful state of the world, we ask: who will bring Father Alex back the memory of life to the people whose hope has been shat- Osei CSSp. tered? As Christians, hope is our virtue. -

The-Problem-With-Vatican-II.Pdf

THE PROBLEM WITH VATICAN II Michael Baker © Copyright Michael Baker 2019 All rights reserved. Apart from fair dealing for the purpose of study, research, criticism or review as permitted under the Copyright Act (C’th) 1968, no part may be reproduced by any process without written permission. Inquiries should be made to the publisher at P O Box 1282, Goulburn NSW 2580. Published by M J Baker in Goulburn, New South Wales, December 2019. This version revised, and shortened, January 2021. Digital conversion by Mark Smith 2 Ad Majoriam Dei Gloriam Our Lady of Perpetual Succour Ave Regina Caelorum, Ave Domina Angelorum. Salve Radix, Salve Porta, ex qua mundo Lux est orta ; Gaude Virgo Gloriosa, super omnes speciosa : Vale, O valde decora, et pro nobis Christum exora. V. Ora pro nobis sancta Dei Genetrix. R. Ut digni efficiamur promissionibus Christi. 3 THE PROBLEM WITH VATICAN II Michael Baker A study, in a series of essays, of the causes of the Second Vatican Council exposing their defects and the harmful consequences that have flowed in the teachings of popes, cardinals and bishops thereafter. This publication is a work of the website superflumina.org The author, Michael Baker, is a retired lawyer who spent some 35 years, first as a barrister and then as a solicitor of the Supreme Court of New South Wales. His authority to offer the commentary and criticism on the philosophical and theological issues embraced in the text lies in his having studied at the feet of Fr Austin M Woodbury S.M., Ph.D., S.T.D., foremost philosopher and theologian of the Catholic Church in Australia in the twentieth century, and his assistant teachers at Sydney’s Aquinas Academy, John Ziegler, Geoffrey Deegan B.A., Ph.D. -

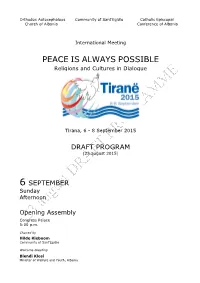

PEACE IS ALWAYS POSSIBLE Religions and Cultures in Dialogue

Orthodox Autocephalous Community of Sant'Egidio Catholic Episcopal Church of Albania Conference of Albania International Meeting PEACE IS ALWAYS POSSIBLE Religions and Cultures in Dialogue Tirana, 6 - 8 September 2015 DRAFT PROGRAM (23 august 2015) 6 SEPTEMBER Sunday Afternoon Opening Assembly Congress Palace 5:00 p.m. Chaired by Hilde Kieboom Community of Sant’Egidio Welcome Greeting Blendi Klosi Minister of Welfare and Youth, Albania Reading of the Message of Pope Francis Opening speeches Edi Rama Prime Minister of Albania Andrea Riccardi Founder of the Community of Sant’Egidio MUSIC Testimony Louis Raphaël I Sako Patriarch of Babylon of the Chaldeans, Iraq Contributions Anastasios Archbishop of Tirana and Primate of the Autocephalous Orthodox Church of Albania David Rosen Former Chief Rabbi of Ireland, AJC, Israel Muhy al-Din Afifi Secretary General of Al-Azhar Al-Sharif Islamic Research Academy, Egypt Sudheendra Kulkarni President of the Research Hindu Foundation of Mumbai, India 7 SEPTEMBER Monday Morning PANEL 1 Orthodox Cathedral, Auditorium 9:30 a.m. The Role of Christian Unity in a Divided World Chaired by Ole Christiam Maele Kvarme Lutheran Bishop, Norway Contributors Emmanuel Orthodox Metropolitan Bishop of France, President of KEK, Ecumenical Patriarchate Enthons Archbishop, Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahedo Church Tamas Fabiny Vice-President of the Lutheran World Federation Ignatiy Orthodox Metropolitan Bishop, Moscow Patriarchate Anders Wejryd Co-President of the World Council of Churches Matteo Zuppi Catholic Bishop, Italy PANEL -

Mediation in Africa Report

Full Study Unpacking the Mystery of Mediation in African Peace Processes Mediation Support Project CSS ETH Zurich © Mediation Support Project (MSP), CSS, and swisspeace 2008 Center for Security Studies (CSS) Swiss Federal Institute of Technology, ETH Zurich Seilergraben 45-49 - SEI CH - 8092 Zürich Tel.: +41-44-632 40 25 Fax: +41-44-632 19 41 [email protected] www.css.ethz.ch swisspeace Sonnenbergstrasse 17 P.O. Box CH - 3000 Bern 7 Tel.: +41-31-330 12 12 Fax: +41-31-330 12 13 [email protected] www.swisspeace.ch/mediation The summary and the full report with references can be accessed at: <www.css.ethz.ch> and <www.swisspeace.ch/mediation> Coordinator: Simon J A Mason Authors: Annika Åberg, Sabina Laederach, David Lanz, Jonathan Litscher, Simon J A Mason, Damiano Sguaitamatti (alphabetical order) Acknowledgements: We are greatly indebted to Murezi Michael of the Swiss Federal Department of Foreign Affairs (FDFA) for initiating and supporting this study project. Without his enthusiasm and perseverance, this study would not have reached such a happy end. Many thanks also to helpful input from Julian Thomas Hottinger, Carol Mottet, and Alain Sigg (Swiss FDFA), Matthias Siegfried (MSP, swisspeace), Mario Giro (St. Egidio) and Katia Papagianni (HD). Thanks also to Christopher Findlay for English proofreading and Marion Ronca (CSS) for layouting. Initiation and Support: Swiss Federal Department of Foreign Affairs (FDFA) Disclaimer: Any opinions expressed in this article present the views of the authors alone, and not those of the CSS, swisspeace, or the Swiss FDFA. Front cover photo: Sudan’s First Vice President Ali Osman Mohamed Taha (L) and Sudan People’s Liberation Move- ment (SPLM) leader John Garang (R) at the signing of the Comprehensive Peace Agreement on the 9 January 2005, ending a 21-year-old conflict in the south that has killed an estimated two million people mainly through famine and disease. -

Mary, the Us Bishops, and the Decade

REVEREND MONSIGNOR JOHN T. MYLER MARY, THE U.S. BISHOPS, AND THE DECADE OF SILENCE: THE 1973 PASTORAL LETTER “BEHOLD YOUR MOTHER WOMAN OF FAITH” A Doctoral Dissertation in Sacred Theology in Marian Studies in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Sacred Theology DIRECTED BY REV. JOHANN G. ROTEN, S.M., S.T.D. INTERNATIONAL MARIAN RESEARCH INSTITUTE UNIVERSITY OF DAYTON DAYTON, OHIO July 19, 2017 Mary, The U.S. Bishops, and the Decade of Silence: The 1973 Pastoral Letter “Behold Your Mother Woman of Faith” © 2017 by Reverend Monsignor John T. Myler ISBN: 978-1-63110-293-6 Nihil obstat: Francois Rossier, S.M.. STD Vidimus et approbamus: Johann G. Roten, S.M., PhD, STD – Director Bertrand A. Buby, S.M., STD – Examinator Thomas A. Thompson, S.M., PhD – Examinator Daytonensis (USA), ex aedibus International Marian Research Institute, et Romae, ex aedibus Pontificiae Facultatis Theologicae Marianum die 19 Julii 2014. All Rights Reserved Under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles or reviews. Printed in the United States of America by Mira Digital Publishing Chesterfield, Missouri 63005 For my Mother and Father, Emma and Bernard – my first teachers in the way of Faith… and for my Bishops, fathers to me during my Priesthood: John Nicholas, James Patrick, Wilton and Edward. Abbreviations Used CTSA Catholic Theological Society of America DVII Documents of Vatican II (Abbott) EV Evangelii Nuntiandi LG Lumen Gentium MC Marialis Cultus MS Marian Studies MSA Mariological Society of America NCCB National Conference of Catholic Bishops NCWN National Catholic Welfare Conference PL Patrologia Latina SC Sacrosanctam Concilium USCCB United States Conference of Catholic Bishops Contents Introduction I. -

Laudato Si.Org

Laudato si' Laudato si' (English: Praise Be to You!) is the second encyclical of Pope Francis. The encyclical has the subtitle "on care for our Laudato si' common home".[1] In it, the pope critiques consumerism and Central Italian for 'Praise Be to irresponsible development, laments environmental degradation and You!' global warming, and calls all people of the world to take "swift and Encyclical letter of Pope unified global action."[2] Francis The encyclical, dated 24 May 2015, was officially published at noon on 18 June 2015, accompanied by a news conference.[2] The Vatican released the document in Italian, German, English, Spanish, French, Polish, Portuguese and Arabic, alongside the original Latin.[3] The encyclical is the second published by Francis, after Lumen fidei Date 24 May 2015 ("The Light of Faith"), which was released in 2013. Since Lumen Subject On care for our common fidei was largely the work of Francis's predecessor Benedict XVI, home Laudato si' is generally viewed as the first encyclical that is entirely the work of Francis.[4][5] Pages 184 Number 2 of 2 of the pontificate Text In Latin (http://w2.vatican. Contents va/content/francesco/la/e ncyclicals/documents/pap Content Environmentalism a-francesco_20150524_e nciclica-laudato-si.html) Poverty Science and modernism In English (http://w2.vatic Technology an.va/content/francesco/e Other topics n/encyclicals/documents/ papa-francesco_2015052 Sources 4_enciclica-laudato-si.htm History l) Early stages Leak Release Reception Within Roman Catholic Church Criticism From other faiths From world leaders From the scientific community Impact on the United States political system Neoconservative critique and counterarguments From industry From other groups In music See also References Further reading Ecological consciousness Global climate change Life of St. -

Sahel and Sub-Saharan Africa Marco Massoni

Sahel and Sub-Saharan Africa Marco Massoni The First Italia-Africa Conference May the 18th 2016, few days before the 53rd anniversary of the founding of the Organization of the African Unity (OAU), now African Union (AU), whose anniversary is celebrated on May 25, the Italian Ministry of Foreign Affairs (MoFA) has hosted the First Italia-Africa Ministerial Conference, which was attended by high-level delegations coming from 52 African countries (out of 54 States), with more than 40 foreign ministers and twenty representatives of international organizations. The event was attended by the highest personalities: the Italian President of the Republic Sergio Mattarella, the Italian former Prime Minister, Matteo Renzi and the Italian former Foreign Minister (now Prime Minister), Paolo Gentiloni, the former President of the African Union Commission (AUC), the South African Nkosazana Dlamini Zuma, the AU Commissioner for Peace and Security, the Algerian Smail Chergui, and the Foreign Minister of Chad, Moussa Faki Mahamat 1 , representing the G-5 Sahel, a group of five Sahelian States (i.e. Burkina Faso, Chad, Mali, Mauritania and Niger), that have formed a reference block for external parties in this extremely difficult and unstable African macro-region. Also Claudio Descalzi (ENI), Mauro Moretti (Finmeccanica), Mario Pezzini (OECD), Matteo Del Fante (Terna), Francesco Starace (ENEL), Morlaye Bangoura (ECOWAS), Elham Ibrahim (UA), Stefano Manservisi (EU - DEVCO), Abdelkader Messahel (Arab League), Mohamed Ibn Chambas (UN), Irene Khan (IDLO), Said Djinnit (UN) and Parfait Onanga-Anyanga (MINUSCA) took part to the event. The Conference was organized into four panels: the first, entitled Italy and Africa. Challenges for a common growth, highlighting the economic sustainability; the second, entitled Environment and Social Development. -

Programme Italy-Africa Conferene

CONFERENZA MINISTERIALE Ministerial Conference/Conférence Ministérielle 18 MAY 2016 8.00 - 9.00 Registration and welcome coffee Sala Mappamondi 9.15 - 10.45 OPENING SESSION Sala Conferenze Internazionali ADDRESS BY > Sergio Mattarella, President of the Italian Republic INTRODUCTORY REMARKS > Paolo Gentiloni, Minister of Foreign Affairs and International Cooperation, Italy > Moussa Faki Mahamat, Minister of Foreign Affairs and African Integration, Republic of Chad > Smail Chergui, Commissioner for Peace and Security, AU 10.45 - 11.00 Break 11.00 - 13.00 PANEL I: ECONOMIC SUSTAINABILITY Sala Conferenze Internazionali Italy and Africa. Challenges for a common growth PARALLEL SESSIONS KEYNOTE SPEECHES > Maurizio Martina, Minister of Agricultural, Food and Forestry Policies, Italy > Kanayo Nwanze, President, IFAD > Fatih Birol, Executive Director, IEA ROUND TABLE > Georges Chikoti, Minister of External Relations, Angola > Alpha Barry, Minister of Foreign Affairs, Burkina Faso > Nii Osah Mills, Minister for Lands and Resources, Ghana > Amina Mohamed, Minister of Foreign Affairs, Kenya > Netumbo Nandi-Ndaitwah, Deputy Prime Minister and Minister of International Relations and Cooperations, Namibia IN COLLABORATION WITH > Jean-Claude Gakosso, Minister of Foreign Affairs, Republic of the Congo > Louise Mushikiwabo, Minister of Foreign Affairs, Rwanda > Abdusalam Omer, Minister of Foreign Affairs, Somalia > Augustine Mahiga, Minister of Foreign Affairs, Tanzania > Robert Dussey, Minister of Foreign Affairs, Togo > Samuel Otsile Outlule, Ambassador, Botswana > Cecilia Obono Ndong, Ambassador, Equatorial Guinea > Sheldon Moulton, Chargé d’Affaires, South Africa > Mohamed Khaled Khiari, Permanent Representative to the UN, Tunisia > Claudio Descalzi, CEO, ENI > Carlo Lambro, President, New Holland Agriculture Global Brand > Mauro Moretti, CEO, Finmeccanica > Mario Pezzini, Director Development Centre, OECD > MODERATOR: Andrea Bignami, Economic journalist, Sky TG24 PANEL II: SOCIO-ENVIRONMENTAL SUSTAINABILITY 11.00 - 13.00 Environment and Social Development. -

Chapter 1 Anthropological Theory

Introduction This dissertation is a historical ethnography of religious diversity in post- revolutionary Nicaragua, a study of religion and politics from the vantage point of Catholics who live in the city of Masaya located on the Pacific side of Nicaragua at the end of the twentieth century. My overarching research question is: How may ethnographically observed patterns in Catholic religious practices in contemporary Nicaragua be understood in historical context? Analysis of religious ritual provides a vehicle for understanding the history of the Nicaraguan struggle to imagine and create a viable nation-state. In Chapter 1, I explain how anthropology benefits by using Max Weber’s social theory as theoretical touchstone for paradigm and theory development. Considering postmodernism problematic for the future of anthropology, I show the value of Weber as a guide to reframing the epistemological questions raised by Michel Foucault and Talal Asad. Situating my discussion of contemporary anthropological theory of religion and ritual within a post-positive discursive framework—provided by a brief comparative analysis of the classical theoretical traditions of Durkheim, Marx, and Weber—I describe the framework used for my analysis of emerging religious pluralism in Nicaragua. My ethnographic and historical methods are discussed in Chapter 2. I utilize the classic methods of participant-observation, including triangulation back and forth between three host families. In every chapter, archival work or secondary historical texts ground the ethnographic data in its relevant historical context. Reflexivity is integrated into my ethnographic research, combining classic ethnography with post-modern narrative methodologies. My attention to reflexivity comes through mainly in the 10 description of my methods and as part of the explanation for my theoretical choices, while the ethnographic descriptions are written up as realist presentations.