Some Kind of Pope

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Information Guide Vatican City

Information Guide Vatican City A guide to information sources on the Vatican City State and the Holy See. Contents Information sources in the ESO database .......................................................... 2 General information ........................................................................................ 2 Culture and language information..................................................................... 2 Defence and security information ..................................................................... 2 Economic information ..................................................................................... 3 Education information ..................................................................................... 3 Employment information ................................................................................. 3 European policies and relations with the European Union .................................... 3 Geographic information and maps .................................................................... 3 Health information ......................................................................................... 3 Human rights information ................................................................................ 4 Intellectual property information ...................................................................... 4 Justice and home affairs information................................................................. 4 Media information ......................................................................................... -

New Directions for AM

ISSUE NUMBER 684 ~THE IIVDUSTRY'S NEWSPAPER N S 1 D E: Widmann Elevated To CBS O &O VP WINTER ARBITRONS CBS VP /Owned AM Stations Nancy Widmann has been pro- FLOODING IN moted to the newly created post Baltimore: WLIF, WBSB roll upward of VP /Owned Radio Stations Boston: WBZ, WXKS -FM neck -and- and will now also oversee the neck company's FM group. She as- sumes the duties of VP /Owned Cleveland: WMMS down to 12, FM Stations Robert Hyland III, WZAK, WMJI up solidly who last week became GM for Dallas: KKDA-FM close to 10, leads KCBS -TV/Los Angeles. big Continuing as the highest- Denver: KBCO breathes down KOSI's ranking woman at CBS Radio, neck Widmann has held many execu- Detroit: WJLB rules roost, WRIF tive positions during her 15 regains AOR lead years with the company, in- Nancy Widmann Houston: KMJO holds lead as KKBQ cluding a six-year stint as VP/ Sales Manager for CBS Radio soars into second GM of WCBS-FM /New York. Spot Sales, and VP /Recruit- She also was VP/GM and N.Y. ment and Placement for CBS, rules Pittsburgh: KDKA Inc. Philadelphia: WEAZ ties WMMR at top Commented CBS Radio Divi- San Francisco: KABL almost beats sion President Bob Hosking, KGO; KMEL top contemporary New Directions For AM "Nancy's proven abilities with Tampa: WRBQ rises higher WHN Drops Country WCFL Becomes our six News and News/Talk stations, plus WCBS -FM, make Washington: WGAY takes lead, WHN Sports For All -Sports Chicago's AM Loop her eminently qualified for this WMZQ -FM vaults to third After more than 14 years in System H&G Communications has new position." Plus ratings for Nassau -Suffolk, Country, WHN /New York was combined the company's two Widmann, who oversees sev- Providence, and San Diego. -

Notes on PCJP Document on Economic Life

Notes on Towards Reforming the International Financial and Monetary Systems in the Context of Global Public Authority The following notes outline some key points in the 2011 document from the Pontifical Council for Justice and Peace, Towards Reforming the International Financial and Monetary Systems in the Context of Global Public Authority. The themes, principles and proposals contained in this Vatican document are based upon Catholic social teaching set forth by Pope John XXIII, Pope Paul VI, and Pope John Paul II as well as, in our present day, by Pope Benedict XVI. In the words of the U.S. bishops, the economy exists to serve the human person, not the other way around. Pope Benedict XVI taught, in his encyclical Caritas in Veritate, that to function correctly, the global economy needs ethics, and these moral dimensions of economic life need to be people-centered. In Caritas in Veritate, Benedict XVI pointed out that not only economic structures failed but trust had been broken. To reform the global economy so that it will be more just, stable and equitable, the Pontifical Council for Justice and Peace uses the teaching of Pope Benedict XVI to call for a new framework and structures of international solidarity and global financial regulation. The Pontifical Council for Justice and Peace argues that the primacy of the spiritual and the ethical needs to be restored, even in economic life. Such an approach will encourage markets and financial institutions that are at the service of the person and capable of responding to the needs of the most vulnerable and the common good. -

A History of English

A History of the English Language PAGE Proofs © John bEnjamins PublishinG company 2nd proofs PAGE Proofs © John bEnjamins PublishinG company 2nd proofs A History of the English Language Revised edition Elly van Gelderen Arizona State University John Benjamins Publishing Company Amsterdam PAGE/ Philadelphia Proofs © John bEnjamins PublishinG company 2nd proofs TM The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of 8 the American National Standard for Information Sciences – Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ansi z39.48-1984. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Gelderen, Elly van. A History of the English Language / Elly van Gelderen. -- Revised edition. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. 1. English language--History. 2. English language--History--Problems, exercises, etc. I. Title. PE1075.G453 2014 420.9--dc23 2014000308 isbn 978 90 272 1208 5 (Hb ; alk. paper) isbn 978 90 272 1209 2 (Pb ; alk. paper) isbn 978 90 272 7043 6 (Eb) © 2014 – John Benjamins B.V. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form, by print, photoprint, microfilm, or any other means, without written permission from the publisher. John Benjamins Publishing Co. · P.O. Box 36224 · 1020 me Amsterdam · The Netherlandspany John Benjamins North America · PP.O. Boxroofs 27519 · Philadelphia pa 19118-0519G com · usa PAGE Publishin Enjamins © John b 2nd proofs Table of contents Preface to the first edition (2006) ix Preface to the revised edition xii Notes to the user and abbreviations xiv List of tables xvi List of figures xix 1 The English language 1 1. The origins and history of English 1 2. -

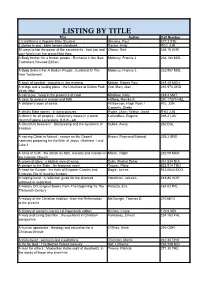

Parish Library Listing

LISTING BY TITLE Title Author Call Number 2 Corinthians (Lifeguide Bible Studies) Stevens, Paul 227.3 STE 3 stories in one : bible heroes storybook Rector, Andy REC JUN 50 ways to tap the power of the sacraments : how you and Ghezzi, Bert 234.16 GHE your family can live grace-filled lives A Body broken for a broken people : Eucharist in the New Moloney, Francis J. 234.163 MOL Testament Revised Edition A Body Broken For A Broken People : Eucharist In The Moloney, Francis J. 232.957 MOL New Testament A book of comfort : thoughts in late evening Mohan, Robert Paul 248.48 MOH A bridge and a resting place : the Ursulines at Dutton Park Ord, Mary Joan 255.974 ORD 1919-1980 A call to joy : living in the presence of God Matthew, Kelly 248.4 MAT A case for peace in reason and faith Hellwig, Monika K. 291.17873 HEL A children's book of saints Williamson, Hugh Ross / WIL JUN Connelly, Sheila A child's Bible stories : in living pictures Ryder, Lilian / Walsh, David RYD JUN A church for all peoples : missionary issues in a world LaVerdiere, Eugene 266.2 LAV church Eugene LaVerdiere, S.S.S - edi A Church to believe in : Discipleship and the dynamics of Dulles, Avery 262 DUL freedom A coming Christ in Advent : essays on the Gospel Brown, Raymond Edward 226.2 BRO narritives preparing for the Birth of Jesus : Matthew 1 and Luke 1 A crisis of truth - the attack on faith, morality and mission in Martin, Ralph 282.09 MAR the Catholic Church A crown of glory : a biblical view of aging Dulin, Rachel Zohar 261.834 DUL A danger to the State : An historical novel Trower, Philip 823.914 TRO A heart for Europe : the lives of Emporer Charles and Bogle, James 943.6044 BOG Empress Zita of Austria-Hungary A helping hand : A reflection guide for the divorced, Horstman, James L. -

A Pope of Their Own

Magnus Lundberg A Pope of their Own El Palmar de Troya and the Palmarian Church UPPSALA STUDIES IN CHURCH HISTORY 1 About the series Uppsala Studies in Church History is a series that is published in the Department of Theology, Uppsala University. The series includes works in both English and Swedish. The volumes are available open-access and only published in digital form. For a list of available titles, see end of the book. About the author Magnus Lundberg is Professor of Church and Mission Studies and Acting Professor of Church History at Uppsala University. He specializes in early modern and modern church and mission history with focus on colonial Latin America. Among his monographs are Mission and Ecstasy: Contemplative Women and Salvation in Colonial Spanish America and the Philippines (2015) and Church Life between the Metropolitan and the Local: Parishes, Parishioners and Parish Priests in Seventeenth-Century Mexico (2011). Personal web site: www.magnuslundberg.net Uppsala Studies in Church History 1 Magnus Lundberg A Pope of their Own El Palmar de Troya and the Palmarian Church Lundberg, Magnus. A Pope of Their Own: Palmar de Troya and the Palmarian Church. Uppsala Studies in Church History 1.Uppsala: Uppsala University, Department of Theology, 2017. ISBN 978-91-984129-0-1 Editor’s address: Uppsala University, Department of Theology, Church History, Box 511, SE-751 20 UPPSALA, Sweden. E-mail: [email protected]. Contents Preface 1 1. Introduction 11 The Religio-Political Context 12 Early Apparitions at El Palmar de Troya 15 Clemente Domínguez and Manuel Alonso 19 2. -

What Is an Apostolic Exhortation? It's a Papal Document That Exhorts

‘Evangelii Gaudium’ and ‘Laudato Si’ All creation “groans in travail” (Rom 8:22) How are we called to a deeper conversion? What is an apostolic exhortation? A papal document that encourages the faithful to implement a particular aspect of the Church’s life and teaching. What is an encyclical? A part of the ordinary magisterium (teaching authority) of the Church Evangelii Gaudium (English: The Joy of the Gospel) is a 2013 apostolic exhortation by Pope Francis on "the church's primary mission of evangelization in the modern world." Evangelii Gaudium What is Pope Francis’ main message in Evangelii Gaudium? The principal theme involves the need for a joyful proclamation of the Gospel to the entire world. “…an Apostolic Exhortation written around the theme of Christian joy in order that the Church may rediscover the original source of evangelisation in the contemporary world” In Evangelii Gaudium Pope Francis’ expresses: Concern that the Church is becoming more judgmental than merciful. He wants a Church that has the outgoing spirit of the pilgrim, as opposed to a Church closed in on itself, languishing in ‘institutional inertia’ He worries that some Catholics have become too attached to the external forms of the faith, while their hearts have grown cold. 6 insights provided by Pope Francis, in EG: 1 God’s inexhaustible mercy. 2 The way of beauty. 3 The ‘revolution of tenderness.’ 4 Humility before Scripture. 5 The wounds of Christ. 6 ‘Faith is always a cross.’ God’s inexhaustible mercy. We are called to renew our commitment to mercy as an external work “The Eucharist, although it is the fullness of sacramental life, is not a prize for the perfect but a powerful medicine and nourishment for the weak.” The way of beauty. -

The Holy See (Including Vatican City State)

COMMITTEE OF EXPERTS ON THE EVALUATION OF ANTI-MONEY LAUNDERING MEASURES AND THE FINANCING OF TERRORISM (MONEYVAL) MONEYVAL(2012)17 Mutual Evaluation Report Anti-Money Laundering and Combating the Financing of Terrorism THE HOLY SEE (INCLUDING VATICAN CITY STATE) 4 July 2012 The Holy See (including Vatican City State) is evaluated by MONEYVAL pursuant to Resolution CM/Res(2011)5 of the Committee of Ministers of 6 April 2011. This evaluation was conducted by MONEYVAL and the report was adopted as a third round mutual evaluation report at its 39 th Plenary (Strasbourg, 2-6 July 2012). © [2012] Committee of experts on the evaluation of anti-money laundering measures and the financing of terrorism (MONEYVAL). All rights reserved. Reproduction is authorised, provided the source is acknowledged, save where otherwise stated. For any use for commercial purposes, no part of this publication may be translated, reproduced or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic (CD-Rom, Internet, etc) or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or any information storage or retrieval system without prior permission in writing from the MONEYVAL Secretariat, Directorate General of Human Rights and Rule of Law, Council of Europe (F-67075 Strasbourg or [email protected] ). 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS I. PREFACE AND SCOPE OF EVALUATION............................................................................................ 5 II. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY....................................................................................................................... -

Integrating Ecology and Justice: the New Papal Encyclical by Mary Evelyn Tucker and John Grim

Feature Integrating Ecology and Justice: The New Papal Encyclical by Mary Evelyn Tucker and John Grim Mat McDermott Una Terra Una Famiglia Humana, One Earth One Family climate march in Vatican City in June 2015. In Brief In June of 2015, Pope Francis released the first encyclical on ecology. The Pope’s message highlights “integral ecology,” intrinsically linking ecological integrity and social justice. While the encyclical notes the statements of prior Popes and Bishops on the environment, Pope Francis has departed from earlier biblical language describing the domination of nature. Instead, he expresses a broader understanding of the beauty and complexity of nature, on which humans fundamentally depend. With “integral ecology” he underscores this connection of humans to the natural environment. This perspective shifts the climate debate to one of a human change of consciousness and conscience. As such, the encyclical has the potential to bring about a tipping point in the global community regarding the climate debate, not merely among Christians, but to all those attending to this moral call to action. 38 | Solutions | July-August 2015 | www.thesolutionsjournal.org n June 18, 2015 Pope Francis thinking. By drawing on and develop- We can compare Pope Francis’ released Laudato Si, the first ing the work of earlier theologians and thinking to the writing of Pope John encyclical in the history of ethicists, this encyclical makes explicit Paul II, who himself builds on Pope O Rerum the Catholic Church on ecology. An the links between social justice and Leo XIII’s progressive encyclical encyclical is the highest-level teaching eco-justice.1 Novarum on workers’ rights in 1891. -

THE CORE THEMES of the ENCYCLICAL FRATELLI TUTTI St

THE CORE THEMES OF THE ENCYCLICAL FRATELLI TUTTI St. John Lateran, 15 November 2020 Card. GIANFRANCO RAVASI Preamble Let us begin from a spiritual account drawn from Tibetan Buddhism, a different world from that of the encyclical, but significant nonetheless. A man walks alone on a desert track that dissolves into the distance on the horizon. He suddenly realises that there is another being, difficult to make out, on the same path. It may be a beast that inhabits these deserted spaces; the traveller’s heart beats faster and faster out of fear, as the wilderness does not offer any shelter or help, so he must continue to walk. As he advances, he discerns the profile: a man’s. However, fear does not leave him; in fact, that man could be a fierce bandit. He has no choice but to go on, as the fear of an assault grips his soul. The traveller no longer has the courage to look up. He can hear the other man’s steps approaching. The two men are now face to face: he looks up and stares at the person before him. In his surprise he cries out: “This is my brother whom I haven’t seen for many years!” We wish to refer to this ancient parable from a different religion and culture at the beginning of this presentation to show that the yearning pervading Pope Francis’s new encyclical Fratelli tutti is an essential component of the spiritual breadth of all humanity. In fact, we find a few unexpected “secular” quotations in the text, such as the 1962 album Samba da Bênção by Brazilian poet and musician Vinicius de Moraes (1913-1980) in which he sang: “Life, for all its confrontations, is the art of encounter” (n. -

How Do the Writings of Pope Benedict XVI on "Transformation" Apply to a Couple's Growth in Holiness in Sacramental Marriage?

The University of Notre Dame Australia ResearchOnline@ND Theses 2018 How do the writings of Pope Benedict XVI on "transformation" apply to a couple's growth in holiness in sacramental marriage? Houda Jilwan The University of Notre Dame Australia Follow this and additional works at: https://researchonline.nd.edu.au/theses Part of the Religion Commons COMMONWEALTH OF AUSTRALIA Copyright Regulations 1969 WARNING The material in this communication may be subject to copyright under the Act. Any further copying or communication of this material by you may be the subject of copyright protection under the Act. Do not remove this notice. Publication Details Jilwan, H. (2018). How do the writings of Pope Benedict XVI on "transformation" apply to a couple's growth in holiness in sacramental marriage? (Master of Philosophy (School of Philosophy and Theology)). University of Notre Dame Australia. https://researchonline.nd.edu.au/theses/194 This dissertation/thesis is brought to you by ResearchOnline@ND. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses by an authorized administrator of ResearchOnline@ND. For more information, please contact [email protected]. HOW DO THE WRITINGS OF POPE BENEDICT XVI ON “TRANSFORMATION” APPLY TO A COUPLE’S GROWTH IN HOLINESS IN SACRAMENTAL MARRIAGE? Houda Jilwan A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of Master of Philosophy School of Philosophy and Theology The University of Notre Dame Australia 2018 Table of Contents Introduction................................................................................................................................ 1 Chapter 1: The universal call to holiness .................................................................................. 11 1.1 Meaning of holiness ..................................................................................................... 11 1.2 A quick overview of the universal call to holiness in Scripture and Tradition .................. -

Why Vatican II Happened the Way It Did, and Who’S to Blame

SPECIAL EDITION SUMMER 2017 Dealing frankly with a messy pontificate, without going off the rails No accidents: why Vatican II happened the way it did, and who’s to blame Losing two under- appreciated traditionalists Bishops on immigration: why can’t we call them what they are? $8.00 Publisher’s Note The nasty personal remarks about Cardinal Burke in a new EDITORIAL OFFICE: book by a key papal advisor, Cardinal Maradiaga, follow a pattern PO Box 1209 of other taunts and putdowns of a sitting cardinal by significant Ridgefield, Connecticut 06877 cardinals like Wuerl and even Ouellette, who know that under [email protected] Pope Francis, foot-kissing is the norm. And everybody half- Your tax-deductible donations for the continu- alert knows that Burke is headed for Church oblivion—which ation of this magazine in print may be sent to is precisely what Wuerl threatened a couple of years ago when Catholic Media Apostolate at this address. he opined that “disloyal” cardinals can lose their red hats. This magazine exists to spotlight problems like this in the PUBLISHER/EDITOR: Church using the print medium of communication. We also Roger A. McCaffrey hope to present solutions, or at least cogent analysis, based upon traditional Catholic teaching and practice. Hence the stress in ASSOCIATE EDITORS: these pages on: Priscilla Smith McCaffrey • New papal blurtations, Church interference in politics, Steven Terenzio and novel practices unheard-of in Church history Original logo for The Traditionalist created by • Traditional Catholic life and beliefs, independent of AdServices of Hollywood, Florida. who is challenging these Can you help us with a donation? The magazine’s cover price SPECIAL THANKS TO: rorate-caeli.blogspot.com and lifesitenews.com is $8.