Pachyderm S P E C I E S S U R V I V a L 1995 Number 19 C O M M I S S I O N Contents

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Health Emergency Information and Risk Assessment Health Emergency Information and Risk Assessment Overview

1 Health Emergency Information and Risk Assessment Health Emergency Information and Risk Assessment Overview This Weekly Bulletin focuses on selected acute public health emergencies Contents occurring in the WHO African Region. The WHO Health Emergencies Programme is currently monitoring 71 events in the region. This week’s edition covers key new and ongoing events, including: 2 Overview Humanitarian crisis in Niger 3 - 6 Ongoing events Ebola virus disease in Democratic Republic of the Congo Humanitarian crisis in Central African Republic 7 Summary of major issues, challenges Cholera in Burundi. and proposed actions For each of these events, a brief description, followed by public health measures implemented and an interpretation of the situation is provided. 8 All events currently being monitored A table is provided at the end of the bulletin with information on all new and ongoing public health events currently being monitored in the region, as well as recent events that have largely been controlled and thus closed. Major issues and challenges include: The humanitarian crisis in Niger and the Central African Republic remains unabated, characterized by continued armed attacks, mass displacement of the population, food insecurity, and limited access to healthcare services. In Niger, the extremely volatile security situation along the borders with Burkina Faso, Mali, and Nigeria occasioned by armed attacks from Non-State Actors as well as resurgence in inter-communal conflicts, is contributing to an unprecedented mass displacement of the population along with its associated consequences. Seasonal flooding with huge impact as well as high morbidity and mortality rates from common infectious diseases have also complicated response to the humanitarian crisis. -

Cameroon | Displacement Report, Far North Region Round 9 | 26 June – 7 July 2017 Cameroon | Displacement Report, Far North Region, Round 9 │ 26 June — 7 July 2017

Cameroon | Displacement Report, Far North Region Round 9 | 26 June – 7 July 2017 Cameroon | Displacement Report, Far North Region, Round 9 │ 26 June — 7 July 2017 The opinions expressed in the report are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the International Organization for Migration (IOM). The designations employed and the presentation of material throughout the report do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of IOM concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area, or of its authorities, or concerning its frontiers or boundaries.1 IOM is committed to the principle that humane and orderly migration benefits migrants and society. As an intergovernmental organization, IOM acts with its partners in the international community to: assist in meeting the operational challenges of migration; advance understanding of migration issues; encourage social and economic development through migration; and uphold the human dignity and well-being of migrants. International Organization for Migration UN House Comice Maroua Far North Region Cameroon Cecilia Mann Tel.: +237 691 794 050 E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.globaldtm.info/cameroon/ © IOM 2017 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without the prior written permission of the publisher. 1 The maps included in this report are illustrative. The representations and the use of borders and geographic names may include errors and do not imply judgment on legal status of territories nor acknowledgement of borders by the Organization. -

Innovative Approaches

INNOVATIVE APPROACHES PREPOSITIONING OBSTETRIC KITS A Strategy for Reducing Maternal and Neonatal Mortality in Health Facilities in the Northern Region of Cameroon CAMEROON PARTNERS: Ministry of Health, UNFPA, SIDA , C2D (The Partnership Framework with France), H4+ Partners JUSTIFICATION OF THE INNOVATION The burden of maternal deaths is of great concern in Cameroon. Among various causes, is the fact that before 2011, in all health facilities including those in the northern region of P H Cameroon, pregnant women were expected to O T pay in advance for care related to delivery and O BY S. TORFINN management of obstetric complications. This prevented access to care for poor women or caused significant delays in the decision to use health facilities, thus leading to an increase in maternal and neonatal mortality in the poorest areas in Cameroon. To address this issue, the Ministry of Health and partners introduced an innovative approach in the northern region of Cameroon, the prepositioning of obstetric kits (birthing kit and emergency caesarean bag) in health facilities. These kits have general use items and medicines for normal vaginal delivery and caesarean delivery respectively. The strategy aims to reduce maternal and neonatal mortality by reducing the third delay (time lost between reaching the facility and initiation of treatment) to access care, especially delayed treatment of obstetric complications and deliveries in these facilities. 1 CAMEROON VE I BACKGROUND INNOVAT APPORACHES Maternal mortality continues to rise in Cameroon, with data reporting an increase of 352 maternal deaths per 100,000 live births from 1998 to 2011 with 430 deaths per 100,000 live births (DHS II, 1998) to 669 maternal deaths per 100,000 live births (DHS III, 2004) then 782 deaths per 100,000 live births (DHS IV, 2011). -

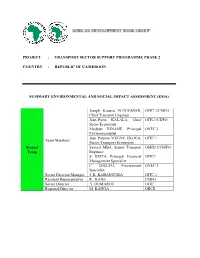

Project : Transport Sector Support Programme Phase 2

PROJECT : TRANSPORT SECTOR SUPPORT PROGRAMME PHASE 2 COUNTRY : REPUBLIC OF CAMEROON SUMMARY ENVIRONMENTAL AND SOCIAL IMPACT ASSESSMENT (ESIA) Joseph Kouassi N’GUESSAN, OITC.1/CMFO Chief Transport Engineer Jean-Pierre KALALA, Chief OITC1/CDFO Socio-Economist Modeste KINANE, Principal ONEC.3 Environmentalist Jean Paterne MEGNE EKOGA, OITC.1 Team Members Senior Transport Economist Project Samuel MBA, Senior Transport OSHD.2/CMFO Team Engineer S. KEITA, Principal Financial OITC1 Management Specialist C. DJEUFO, Procurement ONEC.3 Specialist Sector Division Manager J. K. KABANGUKA OITC.1 Resident Representative R. KANE CMFO Sector Director A. OUMAROU OITC Regional Director M. KANGA ORCE SUMMARY ENVIRONMENTAL AND SOCIAL IMPACT ASSESSMENT (ESIA) Programme Name : Transport Sector Support Programme Phase 2 SAP Code: P-CM-DB0-015 Country : Cameroon Department : OITC Division : OITC-1 1. INTRODUCTION This document is a summary of the Environmental and Social Impact Assessment (ESIA) of the Transport Sector Support Programme Phase 2 which involves the execution of works on the Yaounde-Bafoussam-Bamenda road. The impact assessment of the project was conducted in 2012. This assessment seeks to harmonize and update the previous one conducted in 2012. According to national regulations, the Yaounde-Bafoussam-Babadjou road section rehabilitation project is one of the activities that require the conduct of a full environmental and social impact assessment. This project has been classified under Environmental Category 1 in accordance with the African Development Bank’s Integrated Safeguards System (ISS) of July 2014. This summary has been prepared in accordance with AfDB’s environmental and social impact assessment guidelines and procedures for Category 1 projects. -

Republique Du Cameroun Republic of Cameroon Details Des Projets Par Region, Departement, Chapitre, Programme Et Action Extreme N

REPUBLIQUE DU CAMEROUN REPUBLIC OF CAMEROON PAIX - TRAVAIL - PATRIE PEACE - WORK - FATHERLAND DETAILS DES PROJETS PAR REGION, DEPARTEMENT, CHAPITRE, PROGRAMME ET ACTION OPERATIONS BOOK PER REGION, DIVISION, HEAD, PROGRAMME AND ACTION Exercice/ Financial year : 2017 Région EXTREME NORD Region FAR NORTH Département DIAMARE Division En Milliers de FCFA In Thousand CFAF Année de Tâches démarrage Localité Montant AE Montant CP Tasks Starting Year Locality Montant AE Montant CP Chapitre/Head MINISTERE DE L'ADMINISTRATION TERRITORIALE ET DE LA DECENTRALISATION 07 MINISTRY OF TERRITORIAL ADMINISTRATION AND DECENTRALIZATION PETTE : Reprogrammation des travaux de construction de la sous-préfecture (Phase 1) PETTE 50 000 50 000 2 017 PETTE : Reprogramming of the construction of the Sub-Divisional Office MAROUA: Règlement de la maîtrise d'œuvre pour la construction résidence Préfet MAROUA 5 350 5 350 MAROUA: Payment of the project management of the construction of the residence of 2 017 the SDO MAROUA: Règlement des travaux de la première phase de construction résidence Préfet MAROUA 80 000 80 000 2 017 MAROUA: Payment of the construction of the residence of the SDO Total Chapitre/Head MINATD 135 350 135 350 Chapitre/Head MINISTERE DE LA JUSTICE 08 MINISTRY OF JUSTICE Cour d'Appel de l'Extrême-Nord : Etudes architecturales et géotechniques pour la MAROUA I 40 000 5 000 construction 2 017 Architectural and geotchnical construction studies of the Court of Appeal of Far-North Total Chapitre/Head MINJUSTICE 40 000 5 000 Chapitre/Head MINISTERE DES MARCHES -

Cameroon |Far North Region |Displacement Report Round 15 | 03– 15 September 2018

Cameroon |Far North Region |Displacement Report Round 15 | 03– 15 September 2018 Cameroon | Far North Region | Displacement Report | Round 15 | 03– 15 September 2018 The opinions expressed in the report are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the International Organization for Migration (IOM). The designations employed and the presentation of material throughout the report do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of IOM concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area, or of its authorities, or concerning its frontiers or boundaries1. IOM is committed to the principle that humane and orderly migration benefits migrants and society. As an intergovernmental organization, IOM acts with its partners in the international community to assist in meeting the operational challenges of migration, advance understanding of migration issues, encourage social and economic development through migration and uphold the human dignity and well-being of migrants. International Organization for Migration Cameroon Mission Maroua Sub-Office UN House Comice Maroua Far North Region Cameroon Tel.: +237 222 20 32 78 E-mail: [email protected] Websites: https://ww.iom.int/fr/countries/cameroun and https://displacement.iom.int/cameroon All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without the prior written permission of the publisher. 1The maps included in this report are illustrative. The representations and the use of borders and geographic names may include errors and do not imply judgment on legal status of territories nor acknowledgement of borders by the Organization. -

Rapport De Situation N° 15 Épidémie De Cholera Dans La Région De L’Extrême-Nord Cameroun - 18 Septembre 2019

RAPPORT DE SITUATION N° 15 ÉPIDÉMIE DE CHOLERA DANS LA RÉGION DE L’EXTRÊME-NORD CAMEROUN - 18 SEPTEMBRE 2019 - Réunion du comité Régional de lutte contre le choléra présidé par le Sensibilisation contre le choléra à Boboyo par l’équipe CERPLE, ECD Gouverneur de la Région de l’Extrême-Nord, 12/09/2019 Kaélé et AAEDC/Unicef, Région de l’Extrême-Nord, 08/09/2019 I. FAITS SAILLANTS • 12/09/2019 : Deuxième réunion du comité Régional de Lutte contre la Choléra présidée par le Gouverneur de la région de l’Extrême-Nord ; • 16/09/2019 : 01 nouveau décès hospitalier enregistré dans le district de santé Kaélé, aire de santé Kaélé ; • 3 nouveaux cas notifiés à Zouayé (DS Karhay) après 26 jours de notification zéro ; • À ce jour : o 243 cas suspects enregistrés dans les districts de santé Kaélé, Kar Hay, Moutourwa, Maroua 1 et Guidiguis ; o 08/18 échantillons confirmés par le laboratoire de la CNPS de Maroua ; o 11 décès (dont 04 en communauté et 07 hospitaliers) enregistrés dans les aires de santé Midjivin, Gané, Mindjil et Boboyo ; o Taux de létalité : 4,5%. 1 II. SITUATION ÉPIDÉMIOLOGIQUE Cas Décès 10 8 6 4 Nombre de cas 2 0 7/5/2019 8/4/2019 8/9/2019 9/3/2019 9/8/2019 6/25/2019 6/30/2019 7/10/2019 7/15/2019 7/20/2019 7/25/2019 7/30/2019 8/14/2019 8/19/2019 8/24/2019 8/29/2019 9/13/2019 9/18/2019 Date de début des symptômes Figure 1 : Courbe épidémique des cas suspects et des décès de choléra dans la Région de l’Extrême-Nord, 18/09/2019 Tableau 1 : Résumé de la situation épidémiologique au 18/09/2019 DS DS Binder DS DS Kaélé DS Kar Hay DS Moutourwa -

Patrimoine Et Patrimonialisation Au Cameroun Les Diy-Gid-Biy Des Monts Mandara Septentrionaux Pour Une Étude De Cas

Patrimoine et patrimonialisation au Cameroun Les Diy-gid-biy des monts Mandara septentrionaux pour une étude de cas Thèse Jean-Marie Datouand Djoussou Doctorat en ethnologie et patrimoine Philosophiae Doctor (Ph. D.) Québec, Canada © Jean-Marie Datouang Djoussou, 2014 RÉSUMÉ Portant le titre Patrimoine et patrimonialisation au Cameroun: les Diy-gid-biy des monts Mandara septentrionaux pour une étude de cas, notre thèse est un chainon d'éléments argumentatifs orientés vers l'élucidation du statut de bien patrimonial. Elle s'inscrit dans le champ des recherches considérant le patrimoine et la patrimonialisation comme un ensemble de codes discursifs dont l'intérêt pour l'anthropologue est la compréhension du sens et non de la caractéristique ontique. Il s'agit de l'intelligibilité des rapports aux éléments patrimoniaux qui passe par une mise en évidence de la patrimonialité, l'expression des changements et des conséquences sociaux patrimogènes. De ce fait, le travail met en discours les mises en patrimoine et les rapports sous-tendant le statut d'élément patrimonial. D'une manière générale, c'est un exposé sur le grand paysage patrimonial du Cameroun à travers un regard à la fois vertical et horizontal qui souligne les différentes formes de constructions patrimoniales ayant eu cours dans ledit pays. Il est donc question d‘une mise en relief de l'alchimie de la construction patrimoniale, et donc, du comment les choses deviennent patrimoniales. Pour ce faire, notre thèse se penche sur l'analyse des processus de mise en patrimoine en les considérant dans deux échelles de temps focalisées respectivement sur leur genèse historique et leur construction procédurale actuelle. -

Proceedingsnord of the GENERAL CONFERENCE of LOCAL COUNCILS

REPUBLIC OF CAMEROON REPUBLIQUE DU CAMEROUN Peace - Work - Fatherland Paix - Travail - Patrie ------------------------- ------------------------- MINISTRY OF DECENTRALIZATION MINISTERE DE LA DECENTRALISATION AND LOCAL DEVELOPMENT ET DU DEVELOPPEMENT LOCAL Extrême PROCEEDINGSNord OF THE GENERAL CONFERENCE OF LOCAL COUNCILS Nord Theme: Deepening Decentralization: A New Face for Local Councils in Cameroon Adamaoua Nord-Ouest Yaounde Conference Centre, 6 and 7 February 2019 Sud- Ouest Ouest Centre Littoral Est Sud Published in July 2019 For any information on the General Conference on Local Councils - 2019 edition - or to obtain copies of this publication, please contact: Ministry of Decentralization and Local Development (MINDDEVEL) Website: www.minddevel.gov.cm Facebook: Ministère-de-la-Décentralisation-et-du-Développement-Local Twitter: @minddevelcamer.1 Reviewed by: MINDDEVEL/PRADEC-GIZ These proceedings have been published with the assistance of the German Federal Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development (BMZ) through the Deutsche Gesellschaft für internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ) GmbH in the framework of the Support programme for municipal development (PROMUD). GIZ does not necessarily share the opinions expressed in this publication. The Ministry of Decentralisation and Local Development (MINDDEVEL) is fully responsible for this content. Contents Contents Foreword ..............................................................................................................................................................................5 -

Monthly Humanitarian Situation Report CAMEROON Date: 27Th May 2013

Monthly Humanitarian Situation Report CAMEROON Date: 27th May 2013 Highlights The Health and Nutrition week (SASNIM) was organized in the 10 regions from 26 to 30 April; 1,152,045 children aged 6-59 months received vitamin A and 1,349,937 children aged 12-59 months were dewormed in the Far North and North region. 1,727,391 (101%) children under 5 received Polio drops (OPV), and 38,790 pregnant women received Intermittent Preventive treatment (IPT). A mass screening of acute malnutrition in the North and Far North region was carried out during [the Mother and Child Health and Nutrition Action Week (SASNIM), reaching 90% of children. Out of 1,420,145 children 6-59 months estimated to be covered, 1,288,475 children were enrolled in the mass screening with MUAC, 425,892 in the North region and 862,583 in the Far North. 50,583 MAM cases and 9,269 SAM cases were found and referred to outpatient centres. 10 health districts out of 43 require urgent action. A 10 member delegation led by the UN Foundation team consisting of US Congressional aides and Rotary International visited Garoua - North Region to look at Child Survival and HIV initiatives from April 27 – May 2nd 2013. Following the declaration of state of emergency on May 14 in Nigeria, the actions carried out by Nigerian Government towards the Boko Haram rebels in Maiduguru State (neighbor of Cameroon) may lead to displacement of population from Nigeria to Cameroun. Some Cameroonians living near Nigeria Borno State are moving into Far North region of Cameroon. -

WEEKLY BULLETIN on OUTBREAKS and OTHER EMERGENCIES Week 49: 2 - 8 December 2019 Data As Reported By: 17:00; 8 December 2019

WEEKLY BULLETIN ON OUTBREAKS AND OTHER EMERGENCIES Week 49: 2 - 8 December 2019 Data as reported by: 17:00; 8 December 2019 REGIONAL OFFICE FOR Africa WHO Health Emergencies Programme 1 62 51 12 New event Ongoing events Outbreaks Humanitarian crises 1 179 0 11 1 Mali 1 0 3 1 9 969 54 Senegal 25 916 255 1 0 Niger 1 194 0 Guinea Burkina Faso 52 0 Chad 4 690 18 26 2 2 089 21 Côte d’Ivoire Nigeria Sierra léone 9 0 839 4 South Sudan Ethiopia 804 179 118 2 9 437 7 4 Ghana 3 787 192 Cameroon Central African 3 0 Liberia 3 963 23 Benin Republic 16 0 54 739 0 1 170 14 1 071 53 1 638 40 Togo 55 476 275 1 0 Democratic Republic Uganda 95 20 1 569 5 3 0 of Congo 4 758 37 Congo Kenya 3 320 2 209 1 1 Legend 6 0 2 788 34 269 058 5 430 Measles Humanitarian crisis 11 434 0 26 505 465 Burundi Hepatitis E 7 392 429 2 823 Monkeypox 76 0 50 8 1 064 6 Yellow fever Lassa fever Dengue fever 4 761 95 Cholera Angola Ebola virus disease Rift Valley Fever Comoros 60 0 1 0 Chikungunya 144 0 cVDPV2 Zambia 1 0 Leishmaniasis Malaria Mozambique Floods Plague Cases Namibia Countries reported in the document Deaths Non WHO African Region WHO Member States with no reported events 6 746 56 N W E 3 0 Lesotho 59 0 South Africa 20 0 S Graded events † 3 15 2 Grade 3 events Grade 2 events Grade 1 events 37 22 20 21 Ungraded events PB ProtractedProtracted 3 3 events events Protracted 2 events ProtractedProtracted 1 1 events event 1 Health Emergency Information and Risk Assessment Health Emergency Information and Risk Assessment Health Emergency Information and Risk Assessment Overview This Weekly Bulletin focuses on public health emergencies occurring in the WHO Contents African Region. -

Republique Du Cameroun Ministere De L'energie Et De L'eau Contrat D'affermage Du Service Public De L'alimentation En Eau

REPUBLIQUE DU CAMEROUN MINISTERE DE L'ENERGIE ET DE L’EAU CONTRAT D'AFFERMAGE DU SERVICE PUBLIC DE L’ALIMENTATION EN EAU POTABLE DES CENTRES URBAINS ET PERIURBAINS DU CAMEROUN SOMMAIRE TITRE I – RÉGIME DE L'AFFERMAGE............................................................................... 6 Article 1 - Définitions ..............................................................................................................6 Article 2 - Valeur de l’exposé et des annexes..........................................................................9 Article 3 - Objet du Contrat d'Affermage..................................................................................9 Article 4 - Objet de l’Affermage...............................................................................................9 Article 5 - Définition du Périmètre d'Affermage......................................................................10 Article 6 - Révision du Périmètre d'Affermage.......................................................................10 Article 7 - Biens de retour .....................................................................................................10 Article 8 - Régime de Biens de Retour..................................................................................12 Article 9 - Renouvellement des Biens de Retour ...................................................................13 Article 10 - Inventaire des Biens de Retour.............................................................................13 Article 11 - Biens