Unicode Request for Modifier-Letter Support Background

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

8 December 2004 (Revised 10 January 2005) Topic: Unicode Technical Meeting #101, 15 -18 November 2004, Cupertino, California

To: LSA and UC Berkeley Communities From: Deborah Anderson, UCB representative and LSA liaison Date: 8 December 2004 (revised 10 January 2005) Topic: Unicode Technical Meeting #101, 15 -18 November 2004, Cupertino, California As the UC Berkeley representative and LSA liaison, I am most interested in the proposals for new characters and scripts that were discussed at the UTC, so these topics are the focus of this report. For the full minutes, readers should consult the "Unicode Technical Committee Minutes" web page (http://www.unicode.org/consortum/utc-minutes.html), where the minutes from this meeting will be posted several weeks hence. I. Proposals for New Scripts and Additional Characters A summary of the proposals and the UTC's decisions are listed below. As the proposals discussed below are made public, I will post the URLs on the SEI web page (www.linguistics.berkeley.edu/sei). A. Linguistics Characters Lorna Priest of SIL International submitted three proposals for additional linguistics characters. Most of the characters proposed are used in the orthographies of languages from Africa, Asia, Mexico, Central and South America. (For details on the proposed characters, with a description of their use and an image, see the appendix to this document.) Two characters from these proposals were not approved by the UTC because there are already characters encoded that are very similar. The evidence did not adequately demonstrate that the proposed characters are used distinctively. The two problematical proposed characters were: the modifier straight letter apostrophe (used for a glottal stop, similar to ' APOSTROPHE U+0027) and the Latin small "at" sign (used for Arabic loanwords in an orthography for the Koalib language from the Sudan, similar to @ COMMERCIAL AT U+0040). -

The Unicode Cookbook for Linguists: Managing Writing Systems Using Orthography Profiles

Zurich Open Repository and Archive University of Zurich Main Library Strickhofstrasse 39 CH-8057 Zurich www.zora.uzh.ch Year: 2017 The Unicode Cookbook for Linguists: Managing writing systems using orthography profiles Moran, Steven ; Cysouw, Michael DOI: https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.290662 Posted at the Zurich Open Repository and Archive, University of Zurich ZORA URL: https://doi.org/10.5167/uzh-135400 Monograph The following work is licensed under a Creative Commons: Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0) License. Originally published at: Moran, Steven; Cysouw, Michael (2017). The Unicode Cookbook for Linguists: Managing writing systems using orthography profiles. CERN Data Centre: Zenodo. DOI: https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.290662 The Unicode Cookbook for Linguists Managing writing systems using orthography profiles Steven Moran & Michael Cysouw Change dedication in localmetadata.tex Preface This text is meant as a practical guide for linguists, and programmers, whowork with data in multilingual computational environments. We introduce the basic concepts needed to understand how writing systems and character encodings function, and how they work together. The intersection of the Unicode Standard and the International Phonetic Al- phabet is often not met without frustration by users. Nevertheless, thetwo standards have provided language researchers with a consistent computational architecture needed to process, publish and analyze data from many different languages. We bring to light common, but not always transparent, pitfalls that researchers face when working with Unicode and IPA. Our research uses quantitative methods to compare languages and uncover and clarify their phylogenetic relations. However, the majority of lexical data available from the world’s languages is in author- or document-specific orthogra- phies. -

The Coinage of Akragas C

ACTA UNIVERSITATIS UPSALIENSIS Studia Numismatica Upsaliensia 6:1 STUDIA NUMISMATICA UPSALIENSIA 6:1 The Coinage of Akragas c. 510–406 BC Text and Plates ULLA WESTERMARK I STUDIA NUMISMATICA UPSALIENSIA Editors: Harald Nilsson, Hendrik Mäkeler and Ragnar Hedlund 1. Uppsala University Coin Cabinet. Anglo-Saxon and later British Coins. By Elsa Lindberger. 2006. 2. Münzkabinett der Universität Uppsala. Deutsche Münzen der Wikingerzeit sowie des hohen und späten Mittelalters. By Peter Berghaus and Hendrik Mäkeler. 2006. 3. Uppsala universitets myntkabinett. Svenska vikingatida och medeltida mynt präglade på fastlandet. By Jonas Rundberg and Kjell Holmberg. 2008. 4. Opus mixtum. Uppsatser kring Uppsala universitets myntkabinett. 2009. 5. ”…achieved nothing worthy of memory”. Coinage and authority in the Roman empire c. AD 260–295. By Ragnar Hedlund. 2008. 6:1–2. The Coinage of Akragas c. 510–406 BC. By Ulla Westermark. 2018 7. Musik på medaljer, mynt och jetonger i Nils Uno Fornanders samling. By Eva Wiséhn. 2015. 8. Erik Wallers samling av medicinhistoriska medaljer. By Harald Nilsson. 2013. © Ulla Westermark, 2018 Database right Uppsala University ISSN 1652-7232 ISBN 978-91-513-0269-0 urn:nbn:se:uu:diva-345876 (http://urn.kb.se/resolve?urn=urn:nbn:se:uu:diva-345876) Typeset in Times New Roman by Elin Klingstedt and Magnus Wijk, Uppsala Printed in Sweden on acid-free paper by DanagårdLiTHO AB, Ödeshög 2018 Distributor: Uppsala University Library, Box 510, SE-751 20 Uppsala www.uu.se, [email protected] The publication of this volume has been assisted by generous grants from Uppsala University, Uppsala Sven Svenssons stiftelse för numismatik, Stockholm Gunnar Ekströms stiftelse för numismatisk forskning, Stockholm Faith and Fred Sandstrom, Haverford, PA, USA CONTENTS FOREWORDS ......................................................................................... -

Livret Des Résumés Booklet of Abstracts

34èmes Journées de Linguistique d’Asie Orientale JLAO34 34th Paris Meeting on East Asian Linguistics 7–9 juillet 2021 / July, 7th–9th 2021 Colloque en ligne / Online Conference LIVRET DES RÉSUMÉS BOOKLET OF ABSTRACTS Comité d’organisation/Organizing committee Raoul BLIN, Ludovica LENA, Xin LI, Lin XIAO [email protected] *** Table des matières / Table of contents *** Van Hiep NGUYEN (Keynote speaker): On the study of grammar in Vietnam Julien ANTUNES: Description et analyse de l’accent des composés de type NOM-GENITIF-NOM en japonais moderne Giorgio Francesco ARCODIA: On ‘structural particles’ in Sinitic languages: typology and diachrony Huba BARTOS: Mandarin Chinese post-nuclear glides under -er suffixation Bianca BASCIANO: Degree achievements in Mandarin Chinese: A comparison between 加 jiā+ADJ and 弄 nòng+ADJ verbs Etienne BAUDEL: Chinese and Sino-Japanese lexical items in the Hachijō language of Japan Françoise BOTTERO: Xu Shen’s graphic analysis revisited Tsan Tsai CHAN: Cartographic fieldwork on sentence-final particles – Three challenges and some ways around them Hanzhu CHEN & Meng CHENG: Corrélation entre l’absence d’article et la divergence lexicale Shunting CHEN, Yiming LIANG & Pascal AMSILI: Chinese Inter-clausal Anaphora in Conditionals: A Linear Regression Study Zhuo CHEN: Differentiating two types of Mandarin unconditionals: Their internal and external syntax Katia CHIRKOVA: Aspect, Evidentiality, and Modality in Shuhi Anastasia DURYMANOVA: Nouns and verbs’ syntactic shift: some evidences against Old Chinese parts-of- speech -

A Grammar of Gyeli

A Grammar of Gyeli Dissertation zur Erlangung des akademischen Grades doctor philosophiae (Dr. phil.) eingereicht an der Kultur-, Sozial- und Bildungswissenschaftlichen Fakultät der Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin von M.A. Nadine Grimm, geb. Borchardt geboren am 28.01.1982 in Rheda-Wiedenbrück Präsident der Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin Prof. Dr. Jan-Hendrik Olbertz Dekanin der Kultur-, Sozial- und Bildungswissenschaftlichen Fakultät Prof. Dr. Julia von Blumenthal Gutachter: 1. 2. Tag der mündlichen Prüfung: Table of Contents List of Tables xi List of Figures xii Abbreviations xiii Acknowledgments xv 1 Introduction 1 1.1 The Gyeli Language . 1 1.1.1 The Language’s Name . 2 1.1.2 Classification . 4 1.1.3 Language Contact . 9 1.1.4 Dialects . 14 1.1.5 Language Endangerment . 16 1.1.6 Special Features of Gyeli . 18 1.1.7 Previous Literature . 19 1.2 The Gyeli Speakers . 21 1.2.1 Environment . 21 1.2.2 Subsistence and Culture . 23 1.3 Methodology . 26 1.3.1 The Project . 27 1.3.2 The Construction of a Speech Community . 27 1.3.3 Data . 28 1.4 Structure of the Grammar . 30 2 Phonology 32 2.1 Consonants . 33 2.1.1 Phonemic Inventory . 34 i Nadine Grimm A Grammar of Gyeli 2.1.2 Realization Rules . 42 2.1.2.1 Labial Velars . 43 2.1.2.2 Allophones . 44 2.1.2.3 Pre-glottalization of Labial and Alveolar Stops and the Issue of Implosives . 47 2.1.2.4 Voicing and Devoicing of Stops . 51 2.1.3 Consonant Clusters . -

Linguistic Nature of Prenasalization

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works All Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects 1977 Linguistic Nature of Prenasalization Mark H. Feinstein The Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/2207 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] INFORMATION TO USERS This material was produced from a microfilm copy of the original document. While the most advanced technological means to photograph and reproduce this document have been used, the quality is heavily dependent upon the quality of the original submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help you understand markings or patterns which may appear on this reproduction. 1. The sign or "target" for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is "Missing Page(s)". If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting thru an image and duplicating adjacent pages to insure you complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated w ith a large round black mark, it is an indication that the photographer suspected that the copy may have moved during exposure and thus cause a blurred image. You will find a good image of the page in the adjacent frame. 3. When a map, drawing or chart, etc., was part o f the material being photographed the photographer followed a definite method in "sectioning" the material. -

5892 Cisco Category: Standards Track August 2010 ISSN: 2070-1721

Internet Engineering Task Force (IETF) P. Faltstrom, Ed. Request for Comments: 5892 Cisco Category: Standards Track August 2010 ISSN: 2070-1721 The Unicode Code Points and Internationalized Domain Names for Applications (IDNA) Abstract This document specifies rules for deciding whether a code point, considered in isolation or in context, is a candidate for inclusion in an Internationalized Domain Name (IDN). It is part of the specification of Internationalizing Domain Names in Applications 2008 (IDNA2008). Status of This Memo This is an Internet Standards Track document. This document is a product of the Internet Engineering Task Force (IETF). It represents the consensus of the IETF community. It has received public review and has been approved for publication by the Internet Engineering Steering Group (IESG). Further information on Internet Standards is available in Section 2 of RFC 5741. Information about the current status of this document, any errata, and how to provide feedback on it may be obtained at http://www.rfc-editor.org/info/rfc5892. Copyright Notice Copyright (c) 2010 IETF Trust and the persons identified as the document authors. All rights reserved. This document is subject to BCP 78 and the IETF Trust's Legal Provisions Relating to IETF Documents (http://trustee.ietf.org/license-info) in effect on the date of publication of this document. Please review these documents carefully, as they describe your rights and restrictions with respect to this document. Code Components extracted from this document must include Simplified BSD License text as described in Section 4.e of the Trust Legal Provisions and are provided without warranty as described in the Simplified BSD License. -

Unicode Alphabets for L ATEX

Unicode Alphabets for LATEX Specimen Mikkel Eide Eriksen March 11, 2020 2 Contents MUFI 5 SIL 21 TITUS 29 UNZ 117 3 4 CONTENTS MUFI Using the font PalemonasMUFI(0) from http://mufi.info/. Code MUFI Point Glyph Entity Name Unicode Name E262 � OEligogon LATIN CAPITAL LIGATURE OE WITH OGONEK E268 � Pdblac LATIN CAPITAL LETTER P WITH DOUBLE ACUTE E34E � Vvertline LATIN CAPITAL LETTER V WITH VERTICAL LINE ABOVE E662 � oeligogon LATIN SMALL LIGATURE OE WITH OGONEK E668 � pdblac LATIN SMALL LETTER P WITH DOUBLE ACUTE E74F � vvertline LATIN SMALL LETTER V WITH VERTICAL LINE ABOVE E8A1 � idblstrok LATIN SMALL LETTER I WITH TWO STROKES E8A2 � jdblstrok LATIN SMALL LETTER J WITH TWO STROKES E8A3 � autem LATIN ABBREVIATION SIGN AUTEM E8BB � vslashura LATIN SMALL LETTER V WITH SHORT SLASH ABOVE RIGHT E8BC � vslashuradbl LATIN SMALL LETTER V WITH TWO SHORT SLASHES ABOVE RIGHT E8C1 � thornrarmlig LATIN SMALL LETTER THORN LIGATED WITH ARM OF LATIN SMALL LETTER R E8C2 � Hrarmlig LATIN CAPITAL LETTER H LIGATED WITH ARM OF LATIN SMALL LETTER R E8C3 � hrarmlig LATIN SMALL LETTER H LIGATED WITH ARM OF LATIN SMALL LETTER R E8C5 � krarmlig LATIN SMALL LETTER K LIGATED WITH ARM OF LATIN SMALL LETTER R E8C6 UU UUlig LATIN CAPITAL LIGATURE UU E8C7 uu uulig LATIN SMALL LIGATURE UU E8C8 UE UElig LATIN CAPITAL LIGATURE UE E8C9 ue uelig LATIN SMALL LIGATURE UE E8CE � xslashlradbl LATIN SMALL LETTER X WITH TWO SHORT SLASHES BELOW RIGHT E8D1 æ̊ aeligring LATIN SMALL LETTER AE WITH RING ABOVE E8D3 ǽ̨ aeligogonacute LATIN SMALL LETTER AE WITH OGONEK AND ACUTE 5 6 CONTENTS -

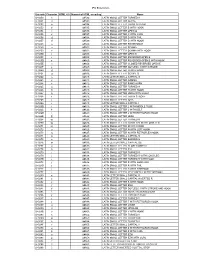

IPA Extensions

IPA Extensions Unicode Character HTML 4.0 Numerical HTML encoding Name U+0250 ɐ ɐ LATIN SMALL LETTER TURNED A U+0251 ɑ ɑ LATIN SMALL LETTER ALPHA U+0252 ɒ ɒ LATIN SMALL LETTER TURNED ALPHA U+0253 ɓ ɓ LATIN SMALL LETTER B WITH HOOK U+0254 ɔ ɔ LATIN SMALL LETTER OPEN O U+0255 ɕ ɕ LATIN SMALL LETTER C WITH CURL U+0256 ɖ ɖ LATIN SMALL LETTER D WITH TAIL U+0257 ɗ ɗ LATIN SMALL LETTER D WITH HOOK U+0258 ɘ ɘ LATIN SMALL LETTER REVERSED E U+0259 ə ə LATIN SMALL LETTER SCHWA U+025A ɚ ɚ LATIN SMALL LETTER SCHWA WITH HOOK U+025B ɛ ɛ LATIN SMALL LETTER OPEN E U+025C ɜ ɜ LATIN SMALL LETTER REVERSED OPEN E U+025D ɝ ɝ LATIN SMALL LETTER REVERSED OPEN E WITH HOOK U+025E ɞ ɞ LATIN SMALL LETTER CLOSED REVERSED OPEN E U+025F ɟ ɟ LATIN SMALL LETTER DOTLESS J WITH STROKE U+0260 ɠ ɠ LATIN SMALL LETTER G WITH HOOK U+0261 ɡ ɡ LATIN SMALL LETTER SCRIPT G U+0262 ɢ ɢ LATIN LETTER SMALL CAPITAL G U+0263 ɣ ɣ LATIN SMALL LETTER GAMMA U+0264 ɤ ɤ LATIN SMALL LETTER RAMS HORN U+0265 ɥ ɥ LATIN SMALL LETTER TURNED H U+0266 ɦ ɦ LATIN SMALL LETTER H WITH HOOK U+0267 ɧ ɧ LATIN SMALL LETTER HENG WITH HOOK U+0268 ɨ ɨ LATIN SMALL LETTER I WITH STROKE U+0269 ɩ ɩ LATIN SMALL LETTER IOTA U+026A ɪ ɪ LATIN LETTER SMALL CAPITAL I U+026B ɫ ɫ LATIN SMALL LETTER L WITH MIDDLE TILDE U+026C ɬ ɬ LATIN SMALL LETTER L WITH BELT U+026D ɭ ɭ LATIN SMALL LETTER L WITH RETROFLEX HOOK U+026E ɮ ɮ LATIN SMALL LETTER LEZH U+026F ɯ ɯ LATIN SMALL -

MUFI Character Recommendation V. 3.0: Alphabetical Order

MUFI character recommendation Characters in the official Unicode Standard and in the Private Use Area for Medieval texts written in the Latin alphabet ⁋ ※ ð ƿ ᵹ ᴆ ※ ¶ ※ Part 1: Alphabetical order ※ Version 3.0 (5 July 2009) ※ Compliant with the Unicode Standard version 5.1 ____________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ ※ Medieval Unicode Font Initiative (MUFI) ※ www.mufi.info ISBN 978-82-8088-402-2 ※ Characters on shaded background belong to the Private Use Area. Please read the introduction p. 11 carefully before using any of these characters. MUFI character recommendation ※ Part 1: alphabetical order version 3.0 p. 2 / 165 Editor Odd Einar Haugen, University of Bergen, Norway. Background Version 1.0 of the MUFI recommendation was published electronically and in hard copy on 8 December 2003. It was the result of an almost two-year-long electronic discussion within the Medieval Unicode Font Initiative (http://www.mufi.info), which was established in July 2001 at the International Medi- eval Congress in Leeds. Version 1.0 contained a total of 828 characters, of which 473 characters were selected from various charts in the official part of the Unicode Standard and 355 were located in the Private Use Area. Version 1.0 of the recommendation is compliant with the Unicode Standard version 4.0. Version 2.0 is a major update, published electronically on 22 December 2006. It contains a few corrections of misprints in version 1.0 and 516 additional char- acters (of which 123 are from charts in the official part of the Unicode Standard and 393 are additions to the Private Use Area). -

Proposal for Superscript Diacritics for Prenasalization, Preglottalization, and Preaspiration

1 Proposal for superscript diacritics for prenasalization, preglottalization, and preaspiration Patricia Keating Department of Linguistics, UCLA [email protected] Daniel Wymark Department of Linguistics, UCLA [email protected] Ryan Sharif Department of Linguistics, UCLA [email protected] ABSTRACT The IPA currently does not specify how to represent prenasalization, preglottalization, or preaspiration. We first review some current transcription practices, and phonetic and phonological literature bearing on the unitary status of prenasalized, preglottalized and preaspirated segments. We then propose that the IPA adopt superscript diacritics placed before a base symbol for these three phenomena. We also suggest how the current IPA Diacritics chart can be modified to allow these diacritics to be fit within the chart. 2 1 Introduction The IPA provides a variety of diacritics which can be added to base symbols in various positions: above ([a͂ ]), below ([n̥ ]), through ([ɫ]), superscript after ([tʰ]), or centered after ([a˞]). Currently, IPA diacritics which modify base symbols are never shown preceding them; the only diacritics which precede are the stress marks, i.e. primary ([ˈ]) and secondary ([ˌ]) stress. Yet, in practice, superscript diacritics are often used preceding base symbols; specifically, they are often used to notate prenasalization, preglottalization and preaspiration. These terms are very common in phonetics and phonology, each having thousands of Google hits. However, none of these phonetic phenomena is included on the IPA chart or mentioned in Part I of the Handbook of the International Phonetic Association (IPA 1999), and thus there is currently no guidance given to users about transcribing them. In this note we review these phenomena, and propose that the Association’s alphabet include superscript diacritics preceding the base symbol for prenasalization, preglottalization and preaspiration, in accord with one common way of transcribing them. -

O. Introduction

Studies in African Linguisticss Volume 26, Number 2, Fall 1997 TWO KINDS OF MORAIC NASAL IN CIYAO* Larry M. Hyman University of California, Berkeley and Annindo S. A. Ngunga University of California, Berkeley Eduardo Mondlane University A problematic issue in a number of Bantu languages concerns the phonological analysis of "preconsonantal nasality", i.e., the question of whether NC entities should be analyzed as single prenasalized consonants or as sequences of nasal + (homorganic) consonant. In this paper, the authors examine two kinds of moraic nasal---one syllabic, one not-in Ciyao, a Bantu language spoken in East Africa. They further demonstrate that there is a third type of preconsonantal nasality in Ciyao which is neither moraic nor syllabic. o. Introduction Among the few problematic issues surrounding the syllabification of consonants in Bantu languages is the proper interpretation of "preconsonantal nasality": For each relevant language of the family, one must first ask whether the sequencing of [+nasal] [-nasal] in forms such as Proto-Bantu *ba-ntu 'people' is properly viewed as a consonant cluster or as a single prenasalized consonant. Noting that * Research on Ciyao has been conducted in the context of the Comparative Bantu On-Line Dictionary (CBOLD) project, supported in part by National Science Foundation Grants #SBR93- 19415 and #SBR96-16330. Earlier versions of this paper were given at D.C. Santa Cruz, Universite Lumiere Lyon2, Universite d' Aix-en-Provence, and the University of Edinburgh. We would like to thank the participants at these presentations as well as Robert Botne and two anonymous reviewers for helpful comments on the paper.