The Hindu, the Muslim, and the Border In

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Complete List of Books in Library Acc No Author Title of Book Subject Publisher Year R.No

Complete List of Books in Library Acc No Author Title of book Subject Publisher Year R.No. 1 Satkari Mookerjee The Jaina Philosophy of PHIL Bharat Jaina Parisat 8/A1 Non-Absolutism 3 Swami Nikilananda Ramakrishna PER/BIO Rider & Co. 17/B2 4 Selwyn Gurney Champion Readings From World ECO `Watts & Co., London 14/B2 & Dorothy Short Religion 6 Bhupendra Datta Swami Vivekananda PER/BIO Nababharat Pub., 17/A3 Calcutta 7 H.D. Lewis The Principal Upanisads PHIL George Allen & Unwin 8/A1 14 Jawaherlal Nehru Buddhist Texts PHIL Bruno Cassirer 8/A1 15 Bhagwat Saran Women In Rgveda PHIL Nada Kishore & Bros., 8/A1 Benares. 15 Bhagwat Saran Upadhya Women in Rgveda LIT 9/B1 16 A.P. Karmarkar The Religions of India PHIL Mira Publishing Lonavla 8/A1 House 17 Shri Krishna Menon Atma-Darshan PHIL Sri Vidya Samiti 8/A1 Atmananda 20 Henri de Lubac S.J. Aspects of Budhism PHIL sheed & ward 8/A1 21 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad Bhagabatam PHIL Dhirendra Nath Bose 8/A2 22 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad PHIL Oriental Pub. 8/A2 Bhagabatam VolI 23 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad PHIL Oriental Pub. 8/A2 Bhagabatam Vo.l III 24 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad Bhagabatam PHIL Oriental Pub. 8/A2 25 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad PHIL Oriental Pub. 8/A2 Bhagabatam Vol.V 26 Mahadev Desai The Gospel of Selfless G/REL Navijvan Press 14/B2 Action 28 Shankar Shankar's Children Art FIC/NOV Yamuna Shankar 2/A2 Number Volume 28 29 Nil The Adyar Library Bulletin LIT The Adyar Library and 9/B2 Research Centre 30 Fraser & Edwards Life And Teaching of PER/BIO Christian Literature 17/A3 Tukaram Society for India 40 Monier Williams Hinduism PHIL Susil Gupta (India) Ltd. -

Writers and Creative Advisors Selected for Drishyam | Sundance Institute Screenwriters Lab in Udaipur, India April 48

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Media contacts: March 23, 2016 Chalena Cadenas 310.360.1981 [email protected] Mauli Singh [email protected] Writers and Creative Advisors Selected for Drishyam | Sundance Institute Screenwriters Lab in Udaipur, India April 48 Lab Recognizes and Supports Six Emerging Independent Filmmakers from India Los Angeles, CA — Sundance Institute and Drishyam Films today announced the artists and creative advisors selected for the second Drishyam | Sundance Institute Screenwriters Lab in Udaipur, India April 48. The Lab supports emerging filmmakers in India, as part of the Institute’s sustained commitment to international artists, which in the last 25 years has included programs in Brazil, Mexico, Jordan, Turkey, Japan, Cuba, Israel and Central Europe. Now in its second year, the fourday Lab is a creative and strategic partnership between Drishyam Films and Sundance Institute, and gives independent screenwriters the opportunity to work intensively on their feature film scripts in an environment that encourages innovation and creative risktaking. The Lab is centered around oneonone story sessions with creative advisors. Screenwriting fellows engage in an artistically rigorous process that offers lessons in craft, a fresh perspective on their work and a platform to fully realize their material. Leading the Lab in India is Drishyam founder, Manish Mundra. He said, “A beautiful heritage city in my hometown of Rajasthan, Udaipur forms an ideal writers retreat, and is the perfect environment for a diverse group of emerging writers and renowned mentors to have a refreshing and productive exchange. Our goal is that the six selected Indian projects, after undergoing a comprehensive mentoring process, will quickly move from script to screen and make their mark globally. -

Movie Aquisitions in 2010 - Hindi Cinema

Movie Aquisitions in 2010 - Hindi Cinema CISCA thanks Professor Nirmal Kumar of Sri Venkateshwara Collega and Meghnath Bhattacharya of AKHRA Ranchi for great assistance in bringing the films to Aarhus. For questions regarding these acquisitions please contact CISCA at [email protected] (Listed by title) Aamir Aandhi Directed by Rajkumar Gupta Directed by Gulzar Produced by Ronnie Screwvala Produced by J. Om Prakash, Gulzar 2008 1975 UTV Spotboy Motion Pictures Filmyug PVT Ltd. Aar Paar Chak De India Directed and produced by Guru Dutt Directed by Shimit Amin 1954 Produced by Aditya Chopra/Yash Chopra Guru Dutt Production 2007 Yash Raj Films Amar Akbar Anthony Anwar Directed and produced by Manmohan Desai Directed by Manish Jha 1977 Produced by Rajesh Singh Hirawat Jain and Company 2007 Dayal Creations Pvt. Ltd. Aparajito (The Unvanquished) Awara Directed and produced by Satyajit Raj Produced and directed by Raj Kapoor 1956 1951 Epic Productions R.K. Films Ltd. Black Bobby Directed and produced by Sanjay Leela Bhansali Directed and produced by Raj Kapoor 2005 1973 Yash Raj Films R.K. Films Ltd. Border Charulata (The Lonely Wife) Directed and produced by J.P. Dutta Directed by Satyajit Raj 1997 1964 J.P. Films RDB Productions Chaudhvin ka Chand Dev D Directed by Mohammed Sadiq Directed by Anurag Kashyap Produced by Guru Dutt Produced by UTV Spotboy, Bindass 1960 2009 Guru Dutt Production UTV Motion Pictures, UTV Spot Boy Devdas Devdas Directed and Produced by Bimal Roy Directed and produced by Sanjay Leela Bhansali 1955 2002 Bimal Roy Productions -

Yash Chopra the Legend

YASH CHOPRA THE LEGEND Visionary. Director. Producer. Legendary Dream Merchant of Indian Cinema. And a trailblazer who paved the way for the Indian entertainment industry. 1932 - 2012 Genre defining director, star-maker and a studio mogul, Yash Chopra has been instrumental in shaping the symbolism of mainstream Hindi cinema across the globe. Popularly known as the ‘King of Romance’ for his string of hit romantic films spanning over a five-decade career, he redefined drama and romance onscreen. Born on 27 September 1932, Yash Chopra's journey began from the lush green fields of Punjab, which kept reappearing in his films in all their splendour. © Yash Raj Films Pvt. Ltd. 1 www.yashrajfilms.com Yash Chopra started out as an assistant to his brother, B. R. Chopra, and went on to direct 5 very successful films for his brother’s banner - B. R. Films, each of which proved to be a significant milestone in his development as a world class director of blockbusters. These were DHOOL KA PHOOL (1959), DHARMPUTRA (1961), WAQT (1965) - India’s first true multi-starrer generational family drama, ITTEFAQ (1969) & AADMI AUR INSAAN (1969). He has wielded the baton additionally for 4 films made by other film companies - JOSHILA (1973), DEEWAAR (1975), TRISHUL (1978) & PARAMPARA (1993). But his greatest repertoire of work were the 50 plus films made under the banner that he launched - the banner that stands for the best of Hindi cinema - YRF. Out of these films, he directed 13 himself and these films have defined much of the language of Hindi films as we know them today. -

Depiction of Real Life Misery Through the Lens of Hindi Film “ Dastak( (1970)”: an Analysis Neema Negi DSVV Uttrakahnd [email protected]

Everant.in/index.php/sshj Survey Report Social Science and Humanities Journal Depiction of Real life misery through the lens of Hindi Film “ Dastak( (1970)”: An Analysis Neema Negi DSVV Uttrakahnd [email protected] ABSTRACT ABSTRACT: Cinema is considered as the tool of social transformation, changing Corresponding Author: agent and the reflection of society. The different eras of Hindi Cinema Neema Negi illustrate the different concern of a common man and their struggle. The various themes represent the image of India with a different approach. Social issues in the earlier eras were the dominant one theme on poverty , unemployment, problem of urban spaces, exploitation of peasants ,corruption, nation and nationalism were the main subject and each storytellers represent those emotions and problems in an ideal way .The present paper analyse the social issues and struggle of a common man and moreover how the director execute the human drama the agony faced by an ordinary people who live in the metropolis and their aspirations of life with the use of metaphors.. Keywords: social issues, metaphors, urban space I- Thematic trends of Hindi Cinema Hindi Cinema deals with diverse themes from last magnificent 100 years . Variety of socially relevant issues cultural issues are addressed by combining them with a fantasies, tradition and myths. Hindi film can be used to know the history of society and culture of India . Indian Cinema has been reflecting social, political and economic dynamics of the national community in it’s narrative since the beginning of the 20th century. The themes such as globalization nation and nationalism, caste, class, gender, terrorism and social issues themes but also suggest cinematic interpretation to solve the problems. -

Bollywood As National(Ist) Cinema Violence, Patriotism and the National- Popular in Rang De Basanti

Third Text, Vol. 23, Issue 6, November, 2009, 703–716 Bollywood as National(ist) Cinema Violence, Patriotism and the National- Popular in Rang De Basanti Neelam Srivastava This essay sets out to explore the relationship between violence, patrio- tism and the national-popular within the medium of film by examining the Indian film-maker Rakeysh Mehra’s recent Bollywood hit, Rang de Basanti (Paint It Saffron, 2006). The film can be seen to form part of a body of work that constructs and represents violence as integral to the emergence of a national identity, or rather, its recuperation. Rang de Basanti is significant in contemporary Indian film production for the enormous resonance it had among South Asian middle-class youth, both in India and in the diaspora. It rewrites, or rather restages, Indian nationalist history not in the customary pacifist Gandhian vein, but in the mode of martyrdom and armed struggle. It represents a more ‘masculine’ version of the nationalist narrative for its contemporary audiences, by retelling the story of the Punjabi revolutionary Bhagat Singh as an Indian hero and as an example for today’s generation. This essay argues that its recuperation of a violent anti-colonial history is, in fact, integral to the middle-class ethos of the film, presenting the viewers with a bourgeois nationalism of immediate and timely appeal, coupled with an accessible (and politically acceptable) social activism. As the 1. Quoted in Namrata Joshi, sociologist Ranjini Majumdar noted, ‘the film successfully fuels the ‘My Yellow Icon’, Outlook middle-class fantasy of corruption being the only problem of the coun- India, online edition, 20 1 February 2006, available try’. -

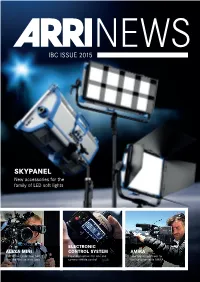

SKYPANEL New Accessories for the Family of LED Soft Lights

NEWS IBC ISSUE 2015 SKYPANEL New accessories for the family of LED soft lights ELECTRONIC ALEXA MINI CONTROL SYSTEM AMIRA Karl Walter Lindenlaub ASC, BVK Expanded options for lens and New application areas for tries the Mini on Nine Lives camera remote control the highly versatile AMIRA EDITORIAL DEAR FRIENDS AND COLLEAGUES We hope you can join postproduction through ARRI Media, illustrating us here at IBC, where we the uniquely broad range of products and services are showcasing our latest we offer. 18 camera systems and lighting technologies. For the ARRI Rental has also been busy supplying the first time in ARRI News we are also introducing our ALEXA 65 system to top DPs on major feature films newest business unit: ARRI Medical. Harnessing – many are testing the large-format camera for the core imaging technology and reliability of selected sequences and then opting to use it on ALEXA, our ARRISCOPE digital surgical microscope main unit throughout production. In April IMAX is already at work in operating theaters, delivering announced that it had chosen ALEXA 65 as the unsurpassed 3D images of surgical procedures. digital platform for 2D IMAX productions. In this issue we share news of how AMIRA is Our new SkyPanel LED soft lights, announced 12 being put to use on productions so diverse and earlier this year and shipping now as promised, are wide-ranging that it has taken even us by surprise. proving extremely popular and at IBC we are The same is true of the ALEXA Mini, which was unveiling a full selection of accessories that will introduced at NAB and has been enthusiastically make them even more flexible. -

Ek Paheli 1971 Mp3 Songs Free Download Ek Nai Paheli

ek paheli 1971 mp3 songs free download Ek Nai Paheli. Ek Nai Paheli is a Hindi album released on 10 Feb 2009. This album is composed by Laxmikant - Pyarelal. Ek Nai Paheli Album has 8 songs sung by Anuradha Paudwal, Lata Mangeshkar, K J Yesudas. Listen to all songs in high quality & download Ek Nai Paheli songs on Gaana.com. Related Tags - Ek Nai Paheli, Ek Nai Paheli Songs, Ek Nai Paheli Songs Download, Download Ek Nai Paheli Songs, Listen Ek Nai Paheli Songs, Ek Nai Paheli MP3 Songs, Anuradha Paudwal, Lata Mangeshkar, K J Yesudas Songs. Ek paheli 1971 mp3 songs free download. "Sunny Leones Ek Paheli Leela Makes Over Rs 15 Cr in Opening Weekend - NDTV Movies. The Indian box office is still reeling from Furious 7's blockbuster earnings of over Rs 80 . Jay Bhanushali: Really happy that people are enjoying 'Ek Paheli Leela' It's Sunny side up: Ek Paheli Leela touches Rs 10.5 crore in two days. More news for Ek Paheli Leela Full Movie Ek Paheli Leela - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia. Ek Paheli Leela is a 2015 Bollywood musical-thriller film, written and directed by Bobby Khan and . The full audio album was released on 10 March 2015. Ek Paheli Leela Online 2015 Official Full Movie | NOORD . 1 day ago - Ek Paheli Leela Online 2015 Official Full Movie; Ek Paheli Leela; 2015 film; 4.8/10·IMDb; Ek Paheli Leela is a 2015 Bollywood musical-thriller . Ek Paheli Leela Full Movie Online Watch Bollywood Full . onlinemoviesgold.com/ek-paheli-leela-full-movie-online-watch- bollywo. -

District Disaster Management Plan- Udupi

DISTRICT DISASTER MANAGEMENT PLAN- UDUPI UDUPI DISTRICT 2015-16 -1- -2- Executive Summary The District Disaster Management Plan is a key part of an emergency management. It will play a significant role to address the unexpected disasters that occur in the district effectively. The information available in DDMP is valuable in terms of its use during disaster. Based on the history of various disasters that occur in the district, the plan has been so designed as an action plan rather than a resource book. Utmost attention has been paid to make it handy, precise rather than bulky one. This plan has been prepared which is based on the guidelines from the National Institute of Disaster Management (NIDM). While preparing this plan, most of the issues, relevant to crisis management, have been carefully dealt with. During the time of disaster there will be a delay before outside help arrives. At first, self-help is essential and depends on a prepared community which is alert and informed. Efforts have been made to collect and develop this plan to make it more applicable and effective to handle any type of disaster. The DDMP developed touch upon some significant issues like Incident Command System (ICS), In fact, the response mechanism, an important part of the plan is designed with the ICS. It is obvious that the ICS, a good model of crisis management has been included in the response part for the first time. It has been the most significant tool for the response manager to deal with the crisis within the limited period and to make optimum use of the available resources. -

World Cinema Amsterd Am 2

WORLD CINEMA AMSTERDAM 2011 3 FOREWORD RAYMOND WALRAVENS 6 WORLD CINEMA AMSTERDAM JURY AWARD 7 OPENING AND CLOSING CEREMONY / AWARDS 8 WORLD CINEMA AMSTERDAM COMPETITION 18 INDIAN CINEMA: COOLLY TAKING ON HOLLYWOOD 20 THE INDIA STORY: WHY WE ARE POISED FOR TAKE-OFF 24 SOUL OF INDIA FEATURES 36 SOUL OF INDIA SHORTS 40 SPECIAL SCREENINGS (OUT OF COMPETITION) 47 WORLD CINEMA AMSTERDAM OPEN AIR 54 PREVIEW, FILM ROUTES AND HET PAROOL FILM DAY 55 PARTIES AND DJS 56 WORLD CINEMA AMSTERDAM ON TOUR 58 THANK YOU 62 INDEX FILMMAKERS A – Z 63 INDEX FILMS A – Z 64 SPONSORS AND PARTNERS WELCOME World Cinema Amsterdam 2011, which takes place WORLD CINEMA AMSTERDAM COMPETITION from 10 to 21 August, will present the best world The 2011 World Cinema Amsterdam competition cinema currently has to offer, with independently program features nine truly exceptional films, taking produced films from Latin America, Asia and Africa. us on a grandiose journey around the world with stops World Cinema Amsterdam is an initiative of in Iran, Kyrgyzstan, India, Congo, Columbia, Argentina independent art cinema Rialto, which has been (twice), Brazil and Turkey and presenting work by promoting the presentation of films and filmmakers established filmmakers as well as directorial debuts by from Africa, Asia and Latin America for many years. new, young talents. In 2006, Rialto started working towards the realization Award winners from renowned international festivals of a long-cherished dream: a self-organized festival such as Cannes and Berlin, but also other films that featuring the many pearls of world cinema. Argentine have captured our attention, will have their Dutch or cinema took center stage at the successful Nuevo Cine European premieres during the festival. -

May 2013 India Review Ambassador’S PAGE America Needs More High-Skilled Worker Visas a Generous Visa Policy for Highly Skilled Workers Would Help Everyone

A Publication of the Embassy of India, Washington, D.C. May 1, 2013 I India RevieI w Vol. 9 Issue 5 www.indianembassy.org IMFC Finance Ministers and Bank Governors during a photo-op at the IMF Headquarters in Washington, D.C. on April 20. Overseas capital best protected in India — Finance Minister P. Chidambaram n India announces n scientist U.R. Rao n Pran honored incentives to boost inducted into with Dadasaheb exports Satellite Hall of Fame Phalke award Ambassador’s PAGE India is ready for U.S. natural gas There is ample evidence that the U.S. economy will benefit if LNG exports are increased he relationship between India and the United States is vibrant and growing. Near its T heart is the subject of energy — how to use and secure it in the cleanest, most efficient way possible. The India-U.S. Energy Dialogue, established in 2005, has allowed our two countries to engage on many issues. Yet as India’s energy needs con - tinue to rise and the U.S. looks to expand the marketplace for its vast cache of energy resources, our partner - ship stands to be strengthened even facilities and ports to distribute it macroeconomic scenarios, and under further. globally. every one of them the U.S. economy Despite the global economic slow - There is a significant potential for would experience a net benefit if LNG down, India’s economy has grown at a U.S. exports of LNG to grow expo - exports were increased. relatively brisk pace over the past five nentially. So far, however, while all ter - A boost in LNG exports would have years and India is now the world’s minals in the U.S. -

Regional Language Books

March 2011 Regional Language Books BENGALI 1 Banerjee, Mamata Aandolaner katha / Mamata Banerjee.-- Kolkata: Dey's Publishing, 2009. 191p.; 21cm. ISBN : 978-81-295-0922-2. B 080 MAM-aan C68922 2 Ahmed, Afsar Jiban jude prahar / Afsar Ahmed.-- Kolkata: Dey's Publishing, 2009. 192p.; 21cm. ISBN : 978-81-295-0875-1. B 891.443 AHM-j C68920 3 Basu, Nabakumar Achhe se nayantaray / Nabakumar Basu.-- Kolkata: Dey's Publishing, 2009. 184p.; 22cm. ISBN : 978-81-295-0870-6. B 891.443 BAS-ac C68921 4 Chakravarti, Smaranjeet Aamader sei shahore / Smaranjeet Chakrabarti.-- Kolkata: Ananda Publications, 2009. 135p.; 22cm. ISBN : 978-81-7756-778-6. B 891.443 CHA-aam C68784 5 Giri, Bhagyadhar Aranye jhar othe / Bhagyadhar Giri.-- Kolkata: Supreme Publishers, 2008. 152p.; 21cm. B 891.443 GIR-ar C68805 6 Maity, Chittaranjan Nirjane khela / Chittaranjan Maity.-- Kolkata: Dey's Publishing, 2009. 368p.; 24cm. ISBN : 978-81-295-0878-2. B 891.44308 MAI-n C68919 7 Indramitra Nerikutta / Indramitra.-- Kolkata: Karukatha, 2008. 108p.; 22cm. B 891.4431 IND-n C68697 8 Mitra, Premendra Bhoot-shikari mejokarta ebong / Premendra Mitra.-- Kolkata: Dey's Publishing, 2009. 199p.; 24cm. ISBN : 978-81-295-0901-7. B 891.4431 MIT-b C68917 9 Maitra, Swapan Kabi Kishorimohan: jiban-o-kabya / Swapan Maitra.-- Kolkata: Manan Prakashan, 2008. 80p.; 21cm. B 928.9144 KIS-m C68918 GUJARATI 10 Valles, Father Dharmamangal / Father Valles.-- Ahmedabad: Gurjar Grantha Ratna Karyalaya, 2009. 240p.; 21cm. ISBN : 978-81-8480-231-3. G 181.4 P9 B193600 11 Muni Vatsalydeep Jain dharma / Muni Vatsalydeep.-- Ahmedabad: Gurjar Grantharatna Karyalaya, 2008.