Soviet-Indian Coproductions: Ali Baba As Political Allegory

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

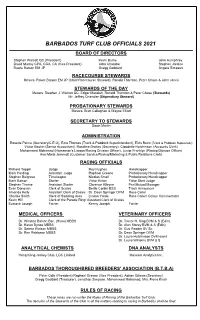

Barbados Turf Club Officials 2021

BARBADOS TURF CLUB OFFICIALS 2021 ___________________________________________________________________________________________________ BOARD OF DIRECTORS Stephen Walcott QC (President) Kevin Burke John Humphrey David Murray CPA, CGA, CA (Vice President) John Chandler Stephen Jardine Rawle Batson EM JP Gregg Goddard Angela Simpson RACECOURSE STEWARDS Messrs. Rawle Batson EM JP (Chief Racecourse Steward), Ronald Thornton, Peter Chase & John Jones STEWARDS OF THE DAY Messrs. Stephen J. Walcott QC, Edgar Massiah, Ronald Thornton & Peter Chase (Stewards) Mr. Jeffrey Chandler (Stipendiary Steward) PROBATIONARY STEWARDS Messrs. Brett Callaghan & Wayne Elliott SECRETARY TO STEWARDS Dawn Martin ADMINISTRATION Rosette Peirce (Secretary/C.E.O), Ezra Thomas (Track & Paddock Superintendent), Elvis Benn (Track & Paddock Supervisor) Victor Gaskin (Senior Accountant), Rosaline Drakes (Secretary), Claudette Hutchinson (Accounts Clerk) Mohommed Mohamad (Horseman’s Liaison/Racing Division Officer), Junior Franklyn (Racing Division Officer) Ann-Maria Jemmott (Customer Service/Racing/Marketing & Public Relations Clerk) RACING OFFICIALS Richard Toppin Judge Roy Hughes Handicapper Mark Harding Assistant Judge Raphael Greene Probationary Handicapper Stephen Belgrave Timekeeper Nicolas Small Probationary Handicapper Mark Batson Starter Victor Kirton False Start Judge Stephen Thorne Assistant Starter Clarence Alleyne Pari Mutual Manager Evan Donovan Clerk of Scales Bertie Corbin BSS Track Announcer Amanda Kelly Assistant Clerk of Scales Dr. Dean Springer DVM Race Caller Charles Smith Clerk of Saddling Area Lindon Yarde Race Caller/ Colour Commentator Kevin Hill Clerk of the Parade Ring/ Assistant Clerk of Scales Eustace Joseph Farrier Kenny Joseph Farrier MEDICAL OFFICERS VETERINARY OFFICERS Dr. Winston Batson Bsc, (Hons) MBBS Dr. Trevor H. King BVM & S (Edin) Dr. Karen Bynoe MBBS Dr. Alan Storey BVM & S (Edin) Dr. Satera Watson MBBS Dr. Gus Reader BV Sc. -

Clare M. Wilkinson-Weber

Clare M. Wilkinson-Weber TAILORING EXPECTATIONS How film costumes become the audience’s clothes ‘Bollywood’ film costume has inspired clothing trends for many years. Female consumers have managed their relation to film costume through negotiations with their tailor as to how film outfits can be modified. These efforts have coincided with, and reinforced, a semiotic of female film costume where eroticized Indian clothing, and most forms of western clothing set the vamp apart from the heroine. Since the late 1980s, consumer capitalism in India has flourished, as have films that combine the display of material excess with conservative moral values. New film costume designers, well connected to the fashion industry, dress heroines in lavish Indian outfits and western clothes; what had previously symbolized the excessive and immoral expression of modernity has become an acceptable marker of global cosmopolitanism. Material scarcity made earlier excessive costume display difficult to achieve. The altered meaning of women’s costume in film corresponds with the availability of ready-to-wear clothing, and the desire and ability of costume designers to intervene in fashion retailing. Most recently, as the volume and diversity of commoditised clothing increases, designers find that sartorial choices ‘‘on the street’’ can inspire them, as they in turn continue to shape consumer choice. Introduction Film’s ability to stimulate consumption (responding to, and further stimulating certain kinds of commodity production) has been amply explored in the case of Hollywood (Eckert, 1990; Stacey, 1994). That the pleasures associated with film going have influenced consumption in India is also true; the impact of film on various fashion trends is recognized by scholars (Dwyer and Patel, 2002, pp. -

Ek Paheli 1971 Mp3 Songs Free Download Ek Nai Paheli

ek paheli 1971 mp3 songs free download Ek Nai Paheli. Ek Nai Paheli is a Hindi album released on 10 Feb 2009. This album is composed by Laxmikant - Pyarelal. Ek Nai Paheli Album has 8 songs sung by Anuradha Paudwal, Lata Mangeshkar, K J Yesudas. Listen to all songs in high quality & download Ek Nai Paheli songs on Gaana.com. Related Tags - Ek Nai Paheli, Ek Nai Paheli Songs, Ek Nai Paheli Songs Download, Download Ek Nai Paheli Songs, Listen Ek Nai Paheli Songs, Ek Nai Paheli MP3 Songs, Anuradha Paudwal, Lata Mangeshkar, K J Yesudas Songs. Ek paheli 1971 mp3 songs free download. "Sunny Leones Ek Paheli Leela Makes Over Rs 15 Cr in Opening Weekend - NDTV Movies. The Indian box office is still reeling from Furious 7's blockbuster earnings of over Rs 80 . Jay Bhanushali: Really happy that people are enjoying 'Ek Paheli Leela' It's Sunny side up: Ek Paheli Leela touches Rs 10.5 crore in two days. More news for Ek Paheli Leela Full Movie Ek Paheli Leela - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia. Ek Paheli Leela is a 2015 Bollywood musical-thriller film, written and directed by Bobby Khan and . The full audio album was released on 10 March 2015. Ek Paheli Leela Online 2015 Official Full Movie | NOORD . 1 day ago - Ek Paheli Leela Online 2015 Official Full Movie; Ek Paheli Leela; 2015 film; 4.8/10·IMDb; Ek Paheli Leela is a 2015 Bollywood musical-thriller . Ek Paheli Leela Full Movie Online Watch Bollywood Full . onlinemoviesgold.com/ek-paheli-leela-full-movie-online-watch- bollywo. -

The Hindu, the Muslim, and the Border In

THE HINDU, THE MUSLIM, AND THE BORDER IN NATIONALIST SOUTH ASIAN CINEMA Vinay Lal University of California, Los Angeles Abstract There is but no question that we can speak about the emergence of the (usually Pakistani or Muslim) ‘terrorist’ figure in many Bollywood films, and likewise there is the indisputable fact of the rise of Hindu nationalism in the political and public sphere. Indian cinema, however, may also be viewed in the backdrop of political developments in Pakistan, where the project of Islamicization can be dated to least the late 1970s and where the turn to a Wahhabi-inspired version of Islam is unmistakable. I argue that the recent history of Pa- kistan must be seen as instigated by a disavowal of the country’s Indic self, and similarly I suggest that scholarly and popular studies of the ‘representation’ of the Muslim in “Bol- lywood” rather too easily assume that such a figure is always the product of caricature and stereotyping. But the border between Pakistan and India, between the self and the other, and the Hindu and the Muslim is rather more porous than we have imagined, and I close with hints at what it means to both retain and subvert the border. Keywords: Border, Communalism, Indian cinema, Nationalism, Pakistan, Partition, Veer-Zaara Resumen 103 Así como el personaje del ‘terrorista’ (generalmente musulmán o paquistaní) está presente en muchos filmes de Bollywood, el nacionalismo hindú está tomando la iniciativa en la esfera política del país. Sin embargo el cine indio también puede hacerse eco de acontecimientos ocurridos en Paquistán, donde desde los años Setenta se ha manifestado un proceso de islamización de la sociedad, con una indudable impronta wahabí. -

Aladdin, Ali Baba, Sinbad and the Tales of Scheherazade Pdf Free

ONE THOUSAND AND ONE ARABIAN NIGHTS : ALADDIN, ALI BABA, SINBAD AND THE TALES OF SCHEHERAZADE Author: Wen-Chin Ouyang Number of Pages: 480 pages Published Date: 17 Nov 2020 Publisher: Flame Tree Publishing Publication Country: London, United Kingdom Language: English ISBN: 9781839642388 DOWNLOAD: ONE THOUSAND AND ONE ARABIAN NIGHTS : ALADDIN, ALI BABA, SINBAD AND THE TALES OF SCHEHERAZADE One Thousand and One Arabian Nights : Aladdin, Ali Baba, Sinbad and the Tales of Scheherazade PDF Book " " " Kaplan MCAT General Chemistry Review: Book OnlineMore people get into medical school with a Kaplan MCAT course than all major courses combined. com This book is a reproduction of an important historical work. The Essential Oils Handbook: All the Oils You Will Ever Need for Health, Vitality and Well-BeingAt the dawn of the 21st century, the old paradigms of medicine have begun to fall apart. Source: Article in Journal of American Dental Association Don't just say, 'Ah!' Be a smart dental consumer and get the best information on one of the most important health investments you can make!A visit to the dentist is about more than just brushing and flossing. Metaphysics Medicine: Restoring Freedom of Thought to the Art and Science of HealingThomas Kuhn's "The Structure of Scientific Revolutions" is one of the best known and most influential books of the 20th century. Intended for advanced undergraduate or graduate courses that conduct cultural or cross-cultural research including cross-(cultural) psychology, culture and psychology, or research methodsdesign courses in psychology, anthropology, sociology, cultural studies, social work, education, geography, international relations, business, nursing, public health, and communication, the book also appeals to researchers interested in conducting cross-cultural and cultural studies. -

SCHEHERAZADE a Musical Fantasy

Alan Gilbert Music Director SCHEHERAZADE A Musical Fantasy School Day Concerts 2013 Resource Materials for Teachers Education at the New York Philharmonic The New York Philharmonic’s education programs open doors to symphonic music for people of all ages and backgrounds, serving over 40,000 young people, families, teachers, and music professionals each year. The School Day Concerts are central to our partnerships with schools in New York City and beyond. The pioneering School Partnership Program joins Philharmonic Teaching Artists with classroom teachers and music teachers in full-year residencies. Currently more than 4,000 students at 16 New York City schools in all five boroughs are participating in the three-year curriculum, gaining skills in playing, singing, listening, and composing. For over 80 years the Young People’s Concerts have introduced children and families to the wonders of orchestral sound; on four Saturday afternoons, the promenades of Avery Fisher Hall become a carnival of hands-on activities, leading into a lively concert. Very Young People’s Concerts engage pre-schoolers in hands-on music-making with members of the New York Philharmonic. The fun and learning continue at home through the Philharmonic’s award-winning website Kidzone! , a virtual world full of games and information designed for young browsers. To learn more about these and the Philharmonic’s many other education programs, visit nyphil.org/education , or go to Kidzone! at nyphilkids.org to start exploring the world of orchestral music right now. The School Day Concerts are made possible with support from the Carson Family Charitable Trust and the Mary and James G. -

Healing of Discernible Brackish from Municipal Drinking Water by Charcoal Filtration Method at Jijgiga, Ethiopia Udhaya Kumar

ISSN XXXX XXXX © 2019 IJESC Research Article Volume 9 Issue No.4 Healing of Discernible Brackish from Municipal Drinking Water by Charcoal Filtration Method at Jijgiga, Ethiopia Udhaya Kumar. K Lecturer Department of Water Resource and Irrigation Engineering University of Jijgiga, Ethiopia Abstract: Jijiga is a city in eastern region of Ethiopia country and the Jijiga is capital of Somali Region (Ethiopia). Located in the Jijiga Zone approximately 80 km (50 miles) east of Harar and 60 km (37 miles) west of the border with Somalia, this city has an elevation of 1,609 meters above the sea level. The population of this city was 185000 in the year 2015. The elevation of this city is 1609m from sea level. The natural water source for jijiga is limited, most of the time people getting limited quantity of water. The main source of this city is a small pond and one spring. The rainy season also not that much. The municipality supplying water to every house based upon intermittent system, the time limit is morning only (8am to 9am). The municipality water contains discernible brackish. The public using this water for drinking and cooking purpose, it wills danger for human health. My focus is planning to remove discernible brackish by distinct method. My research results indicate the removal of discernible brackish from drinking water by simple charcoal filtration method for low cost. Keywords: Discernible brackish, Human health, Filtration, Low cost, Main source, Municipality, Intermittent system, Distinct method. I. INTRODUCTION charcoal. Only the water is reached to the second layer. Then the filtered water is collected separately to another container The climate condition of Jijgiga city is not constant and also without discernible brackish. -

Socialist Realism Seen in Maxim Gorky's Play The

SOCIALIST REALISM SEEN IN MAXIM GORKY’S PLAY THE LOWER DEPTHS AN UNDERGRADUATE THESIS Presented as Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements for the Degree of Sarjana Sastra in English Letters By AINUL LISA Student Number: 014214114 ENGLISH LETTERS STUDY PROGRAMME DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH LETTERS FACULTY OF LETTERS SANATA DHARMA UNIVERSITY YOGYAKARTA 2009 SOCIALIST REALISM SEEN IN MAXIM GORKY’S PLAY THE LOWER DEPTHS AN UNDERGRADUATE THESIS Presented as Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements for the Degree of Sarjana Sastra in English Letters By AINUL LISA Student Number: 014214114 ENGLISH LETTERS STUDY PROGRAMME DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH LETTERS FACULTY OF LETTERS SANATA DHARMA UNIVERSITY YOGYAKARTA 2009 i ii iii HHaappppiinneessss aallwwaayyss llooookkss ssmmaallll wwhhiillee yyoouu hhoolldd iitt iinn yyoouurr hhaannddss,, bbuutt lleett iitt ggoo,, aanndd yyoouu lleeaarrnn aatt oonnccee hhooww bbiigg aanndd pprreecciioouuss iitt iiss.. (Maxiim Gorky) iv Thiis Undergraduatte Thesiis iis dediicatted tto:: My Dear Mom and Dad,, My Belloved Brotther and Siistters.. v vi ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Firstly, I would like to praise Allah SWT for the blessings during the long process of this undergraduate thesis writing. I would also like to thank my patient and supportive father and mother for upholding me, giving me adequate facilities all through my study, and encouragement during the writing of this undergraduate thesis, my brother and sisters, who are always there to listen to all of my problems. I am very grateful to my advisor Gabriel Fajar Sasmita Aji, S.S., M.Hum. for helping me doing my undergraduate thesis with his advice, guidance, and patience during the writing of my undergraduate thesis. My gratitude also goes to my co-advisor Dewi Widyastuti, S.Pd., M.Hum. -

A Love Story of Fantasy and Fascination: Exigency of Indian Cinema in Nigeria

Annals of the Academy of Romanian Scientists Series on Philosophy, Psychology, Theology and Journalism 80 Volume 9, Number 1–2/2017 ISSN 2067 – 113x A LOVE STORY OF FANTASY AND FASCINATION: EXIGENCY OF INDIAN CINEMA IN NIGERIA Kaveri Devi MISHRA Abstract. The prevalence of Indian cinema in Nigeria has been very interesting since early 1950s. The first Indian movie introduced in Nigeria was “Mother India”, which was a blockbuster across Asia, Africa, central Asia and India. It became one of the most popular films among the Nigerians. Majority of the people were able to relate this movie along story line. It was largely appreciated and well received across all age groups. There has been a lot of similarity of attitudes within Indian and Nigerian who were enjoying freedom after the oppression and struggle against colonialism. During 1970’s Indian cinema brought in a new genre portraying joy and happiness. This genre of movies appeared with vibrant and bold colors, singing, dancing sharing family bond was a big hit in Nigeria. This paper examines the journey of Indian Cinema in Nigeria instituting love and fantasy. It also traces the success of cultural bonding between two countries disseminating strong cultural exchanges thereof. Keywords: Indian cinema, Bollywood, Nigeria. Introduction: Backdrop of Indian Cinema Indian Cinema (Bollywood) is one of the most vibrant and entertaining industries on earth. In 1896 the Lumière brothers, introduced the art of cinema in India by setting up the industry with the screening of few short films for limited audience in Bombay (present Mumbai). The turning point for Indian Cinema came into being in 1913 when Dada Saheb Phalke considered as the father of Indian Cinema. -

Rhythm, Dance, and Resistance in the New Orleans Second Line

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles “We Made It Through That Water”: Rhythm, Dance, and Resistance in the New Orleans Second Line A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Ethnomusicology by Benjamin Grant Doleac 2018 © Copyright by Benjamin Grant Doleac 2018 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION “We Made It Through That Water”: Rhythm, Dance, and Resistance in the New Orleans Second Line by Benjamin Grant Doleac Doctor of Philosophy in Ethnomusicology University of California, Los Angeles, 2018 Professor Cheryl L. Keyes, Chair The black brass band parade known as the second line has been a staple of New Orleans culture for nearly 150 years. Through more than a century of social, political and demographic upheaval, the second line has persisted as an institution in the city’s black community, with its swinging march beats and emphasis on collective improvisation eventually giving rise to jazz, funk, and a multitude of other popular genres both locally and around the world. More than any other local custom, the second line served as a crucible in which the participatory, syncretic character of black music in New Orleans took shape. While the beat of the second line reverberates far beyond the city limits today, the neighborhoods that provide the parade’s sustenance face grave challenges to their existence. Ten years after Hurricane Katrina tore up the economic and cultural fabric of New Orleans, these largely poor communities are plagued on one side by underfunded schools and internecine violence, and on the other by the rising tide of post-disaster gentrification and the redlining-in- disguise of neoliberal urban policy. -

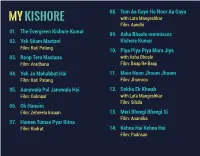

Kishore Booklet Copy

08. Tum Aa Gaye Ho Noor Aa Gaya with Lata Mangeshkar Film: Aandhi 01. The Evergreen Kishore Kumar 09. Asha Bhosle reminisces 02. Yeh Sham Mastani Kishore Kumar Film: Kati Patang 10. Piya Piya Piya Mora Jiya 03. Roop Tera Mastana with Asha Bhosle Film: Aradhana Film: Baap Re Baap 04. Yeh Jo Mohabbat Hai 11. Main Hoon Jhoom Jhoom Film: Kati Patang Film: Jhumroo 05. Aanewala Pal Janewala Hai 12. Dekha Ek Khwab Film: Golmaal with Lata Mangeshkar Film: Silsila 06. Oh Hansini Film: Zehreela Insaan 13. Meri Bheegi Bheegi Si Film: Anamika 07. Hamen Tumse Pyar Kitna Film: Kudrat 14. Kehna Hai Kehna Hai Film: Padosan 2 3 15. Raat Kali Ek Khwab Mein 23. Mere Sapnon Ki Rani Film: Buddha Mil Gaya Film: Aradhana 16. Aate Jate Khoobsurat Awara 24. Dil Hai Mera Dil Film: Anurodh Film: Paraya Dhan 17. Khwab Ho Tum Ya Koi 25. Mere Dil Mein Aaj Kya Hai Film: Teen Devian Film: Daag 18. Aasman Ke Neeche 26. Ghum Hai Kisi Ke Pyar Mein with Lata Mangeshkar with Lata Mangeshkar Film: Jewel Thief Film: Raampur Ka Lakshman 19. Mere Mehboob Qayamat Hogi 27. Aap Ki Ankhon Mein Kuch Film: Mr. X In Bombay with Lata Mangeshkar Film: Ghar 20. Teri Duniya Se Hoke Film: Pavitra Papi 28. Sama Hai Suhana Suhana Film: Ghar Ghar Ki Kahani 21. Kuchh To Log Kahenge Film: Amar Prem 29. O Mere Dil Ke Chain Film: Mere Jeevan Saathi 22. Rajesh Khanna talks about Kishore Kumar 4 5 30. Musafir Hoon Yaron 38. Gaata Rahe Mera Dil Film: Parichay with Lata Mangeshkar Film: Guide 31. -

Download Disco Dancer Movie

Download disco dancer movie Disco Dancer Movie HD Video. Disco Dancer - Mithun Chakraborty | Kim Yashpal - Superhit Hindi Movie - (With Eng Subtitles) by Shemaroo Download. Disco Dancer () - Hindi Full Movie - Mithun Chakraborty - Bollywood Superhit 80's Movie by Shemaroo Movies Download. I am a disco dancer... at first Disco star Mithun da in India. All Songs of Disco Dancer {HD} - Mithun. Watch Disco Dancer - Mithun Chakraborty - Bollywood Superhit 80's Classic Movie - Full Length - High. disco-dancer-wallpaper. Direct Download Links For Hindi Movie Disco Dancer MP3 Songs: Song Name, ( Kbps). 01 I Am A Disco Dancer, Download. Drama · Jimmy promises to return to Bombay and become a famous entertainer so that he can .. Trivia. one of the earliest film of Om Puri where he acted in mainstream cinema. See more» Photography · Audible Download Audio Books. Download Disco Dancer () Songs Indian Movies Hindi Mp3 Songs, Disco Dancer () Mp3 Songs Zip file. Free High quality Mp3 Songs Download. A street singer and dancer, Anil has the burning ambition to make it big as a disco dancer. Overcoming obstacles he becomes Jimmy, the rage of disco dancing. Download Disco Dancer bollwood Mp3 Songs. Disco Dancer BollyWood Mp3. Disco Dancer Movie Cast and Crew. songs cover preview. Movie/Folder Name. Download Disco Dancer Array Full Mp3 Songs By Kishore Kumar Movie - Album Released On 16 Mar, in Category Hindi - Mr-Jatt. Disco Dancer () Hindi mp3 songs download, Kim, Mithun Chakraborty Disco Dancer Songs Free Download, Disco Dancer () old movie mp3 songs. Disco Dancer Songs PK Download, Disco Dancer Mp3 Song Free Download, Disco Dancer Movie Songs Mp3 Download,Disco Dancer Film PK Song.