Clare M. Wilkinson-Weber

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

EDITED TRANSCRIPT Eros STX Global Corporation – Business Update Call

NOVEMBER 04, 2020 / 9:30PM GMT, Eros STX Global Corporation – Business Update Call REFINITIV STREETEVENTS EDITED TRANSCRIPT Eros STX Global Corporation – Business Update Call EVENT DATE/TIME: NOVEMBER 04, 2020 / 9:30PM GMT REFINITIV STREETEVENTS | www.refinitiv.com | Contact Us ©2020 Refinitiv. All rights reserved. Republication or redistribution of Refinitiv content, including by framing or similar means, is prohibited without the prior written consent of Refinitiv. 'Refinitiv' and the Refinitiv logo are registered trademarks of Refinitiv and its affiliated companies. 1 NOVEMBER 04, 2020 / 9:30PM GMT, Eros STX Global Corporation – Business Update Call CORPORATE PARTICIPANTS Adam Fogelson: STX Films - Chairman Andy Warren: Eros STX Global Corporation - CFO Bob Simonds: Eros STX Global Corporation - Co-Chairman & CEO Drew Borst: Eros STX Global Corporation - EVP Investor Relations & Business Development Noah Fogelson: Eros STX Global Corporation - Co-President Rishika Lulla Singh: Eros STX Global Corporation - Co-President & Director CONFERENCE CALL PARTICIPANTS Eric Katz, Wolfe Research, LLC - Research Analyst Robert Routh, FBN Securities, Inc., Research Division - Research Analyst Robert Fishman, MoffettNathanson LLC - Analyst Ted Cronin, Citigroup Inc., Research Division - Research Analyst Tim Nollen, Macquarie Research - Senior Media Analyst PRESENTATION Operator Good afternoon, ladies and gentlemen, and welcome to Eros STX Global Corporation Business Update Call. This call is being broadcast live on the Internet, and a replay of the call will be available on the company's website. The company published earlier certain financial information, including a 20-F transition report and 6-K filing which are available on the company's website. The company would like to remind everyone listening that during this call, it will be making forward- looking statements under the safe harbor provisions of the federal securities laws. -

Movie Aquisitions in 2010 - Hindi Cinema

Movie Aquisitions in 2010 - Hindi Cinema CISCA thanks Professor Nirmal Kumar of Sri Venkateshwara Collega and Meghnath Bhattacharya of AKHRA Ranchi for great assistance in bringing the films to Aarhus. For questions regarding these acquisitions please contact CISCA at [email protected] (Listed by title) Aamir Aandhi Directed by Rajkumar Gupta Directed by Gulzar Produced by Ronnie Screwvala Produced by J. Om Prakash, Gulzar 2008 1975 UTV Spotboy Motion Pictures Filmyug PVT Ltd. Aar Paar Chak De India Directed and produced by Guru Dutt Directed by Shimit Amin 1954 Produced by Aditya Chopra/Yash Chopra Guru Dutt Production 2007 Yash Raj Films Amar Akbar Anthony Anwar Directed and produced by Manmohan Desai Directed by Manish Jha 1977 Produced by Rajesh Singh Hirawat Jain and Company 2007 Dayal Creations Pvt. Ltd. Aparajito (The Unvanquished) Awara Directed and produced by Satyajit Raj Produced and directed by Raj Kapoor 1956 1951 Epic Productions R.K. Films Ltd. Black Bobby Directed and produced by Sanjay Leela Bhansali Directed and produced by Raj Kapoor 2005 1973 Yash Raj Films R.K. Films Ltd. Border Charulata (The Lonely Wife) Directed and produced by J.P. Dutta Directed by Satyajit Raj 1997 1964 J.P. Films RDB Productions Chaudhvin ka Chand Dev D Directed by Mohammed Sadiq Directed by Anurag Kashyap Produced by Guru Dutt Produced by UTV Spotboy, Bindass 1960 2009 Guru Dutt Production UTV Motion Pictures, UTV Spot Boy Devdas Devdas Directed and Produced by Bimal Roy Directed and produced by Sanjay Leela Bhansali 1955 2002 Bimal Roy Productions -

Karan and Jennifer Divorce

Karan And Jennifer Divorce Arillate Isaak sometimes frazzling any alarmists knifes mickle. Donald is disreputable: she underprizing memoriter and defoliated her Chiba. Pinnulate Isaiah still boults: verminous and home Vincents hewn quite fallibly but telphers her underlinen electrometrically. It's appropriate between Karan Singh Grover and Jennifer Winget. There is one of her own engaging and karan and jennifer divorce and i generally up with. Karan Singh Grover's Ex-Wife Jennifer Winget Comments On. The opening got married in 2012 to reach get divorced in 2016 The rumors spread like wildfire that Karan cheated on Jennifer with his family wife. Finally in 2016 Jennifer divorced Karan and he married Bipasha Basu Despite saying that Jennifer has congratulated the quiet couple Karan and Bipasha She said her wish my good luck and text happy married life. Karan jennifer divorce News Pinkvilla. Message field is divorce karan and jennifer winget next generation. Jennifer Winget and Karan Singh Grover Headed For this Divorce. Twitter split Karan Singh Grover announces divorce while wife Jennifer Winget The actor on Monday took to Twitter to earth his terms with. Jennifer Winget-Karan Singh Grover Split 'Alone' Actor Says. Is Jennifer Winget dating 'Code M' co-star Tanuj Virwani Tv. 5 things Jennifer Winget revealed about her failed marriage. Karan and Jennifer heading towards divorce This might come as rough rude men to all Karan Singh Grover and Jennifer Winget as we slow that between two very long. Parting Ways Karan Singh Grover And Jennifer Winget To. Jennifer Winget Finally Reacts on Karan Singh Grover and Bipasa Basu Marriage or Her DivorceJennifer took a replace of fly to talk like her. -

Yash Chopra the Legend

YASH CHOPRA THE LEGEND Visionary. Director. Producer. Legendary Dream Merchant of Indian Cinema. And a trailblazer who paved the way for the Indian entertainment industry. 1932 - 2012 Genre defining director, star-maker and a studio mogul, Yash Chopra has been instrumental in shaping the symbolism of mainstream Hindi cinema across the globe. Popularly known as the ‘King of Romance’ for his string of hit romantic films spanning over a five-decade career, he redefined drama and romance onscreen. Born on 27 September 1932, Yash Chopra's journey began from the lush green fields of Punjab, which kept reappearing in his films in all their splendour. © Yash Raj Films Pvt. Ltd. 1 www.yashrajfilms.com Yash Chopra started out as an assistant to his brother, B. R. Chopra, and went on to direct 5 very successful films for his brother’s banner - B. R. Films, each of which proved to be a significant milestone in his development as a world class director of blockbusters. These were DHOOL KA PHOOL (1959), DHARMPUTRA (1961), WAQT (1965) - India’s first true multi-starrer generational family drama, ITTEFAQ (1969) & AADMI AUR INSAAN (1969). He has wielded the baton additionally for 4 films made by other film companies - JOSHILA (1973), DEEWAAR (1975), TRISHUL (1978) & PARAMPARA (1993). But his greatest repertoire of work were the 50 plus films made under the banner that he launched - the banner that stands for the best of Hindi cinema - YRF. Out of these films, he directed 13 himself and these films have defined much of the language of Hindi films as we know them today. -

Naushad Aan Mp3, Flac, Wma

Naushad Aan mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Pop / Folk, World, & Country / Stage & Screen Album: Aan Country: India Released: 1983 Style: Hindustani, Bollywood, Soundtrack MP3 version RAR size: 1240 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1369 mb WMA version RAR size: 1829 mb Rating: 4.7 Votes: 380 Other Formats: ADX MMF MP3 VQF AIFF AUD MP4 Tracklist A1 –Mohd. Rafi* Man Mera Ehsan A2 –Shamshad Begum Aag Lagi Tanman Men A3 –Lata Mangeshkar Tujhe Kho Diya Hamne A4 –Mohd. Rafi* Mohabbat Choome Jinke Hath A5 –Shamshad Begum, Lata Mangeshkar, Mohd. Rafi* & Chorus* Gao Tarane Man Ke B1 –Mohd. Rafi* Dil Men Chhupa Ke B2 –Lata Mangeshkar & Chorus* Aaj Mere Man Men Sakhi B3 –Shamshad Begum Main Rani Hoon Raja Ki B4 –Mohd. Rafi* Takra Gaya Tumse B5 –Shamshad Begum, Lata Mangeshkar & Chorus* Khelo Rang Hamare Sang Companies, etc. Record Company – EMI Copyright (c) – The Gramophone Company Of India Ltd. Phonographic Copyright (p) – The Gramophone Company Of India Ltd. Manufactured By – The Gramophone Company Of India Ltd. Distributed By – The Gramophone Company Of India Ltd. Printed By – Printwell Credits Lyrics By – Shakeel Badayuni Music By – Naushad Notes From The Original Soundtrack Hindi movie - Aan Other versions Category Artist Title (Format) Label Category Country Year New Light , 10001, IND 6048-C Naushad Aan (LP) 10001, IND 6048-C 1955 New Light LKDA-350 Naushad Aan (LP) Odeon LKDA-350 Pakistan 1980 Related Music albums to Aan by Naushad Laxmikant Pyarelal - Farz / Jigri Dost Naushad - Baiju Bawra Shankar Jaikishan / S. D. Burman - Jab Pyar Kisi Se Hota Hai / Asli Naqli / Tere Ghar Ke Samne Salil Chowdhury, Shankar-Jaikishan - Maya / Love Marriage Roshan , Sahir - Barsat Ki Rat / Taj Mahal Mohd. -

The West Bengal College Service Commission State

THE WEST BENGAL COLLEGE SERVICE COMMISSION STATE ELIGIBILITY TEST Subject: MUSIC Code No.: 28 SYLLABUS Hindustani (Vocal, Instrumental & Musicology), Karnataka, Percussion and Rabindra Sangeet Note:- Unit-I, II, III & IV are common to all in music Unit-V to X are subject specific in music Unit-I Technical Terms: Sangeet, Nada: ahata & anahata , Shruti & its five jaties, Seven Vedic Swaras, Seven Swaras used in Gandharva, Suddha & Vikrit Swara, Vadi- Samvadi, Anuvadi-Vivadi, Saptak, Aroha, Avaroha, Pakad / vishesa sanchara, Purvanga, Uttaranga, Audava, Shadava, Sampoorna, Varna, Alankara, Alapa, Tana, Gamaka, Alpatva-Bahutva, Graha, Ansha, Nyasa, Apanyas, Avirbhav,Tirobhava, Geeta; Gandharva, Gana, Marga Sangeeta, Deshi Sangeeta, Kutapa, Vrinda, Vaggeyakara Mela, Thata, Raga, Upanga ,Bhashanga ,Meend, Khatka, Murki, Soot, Gat, Jod, Jhala, Ghaseet, Baj, Harmony and Melody, Tala, laya and different layakari, common talas in Hindustani music, Sapta Talas and 35 Talas, Taladasa pranas, Yati, Theka, Matra, Vibhag, Tali, Khali, Quida, Peshkar, Uthaan, Gat, Paran, Rela, Tihai, Chakradar, Laggi, Ladi, Marga-Deshi Tala, Avartana, Sama, Vishama, Atita, Anagata, Dasvidha Gamakas, Panchdasa Gamakas ,Katapayadi scheme, Names of 12 Chakras, Twelve Swarasthanas, Niraval, Sangati, Mudra, Shadangas , Alapana, Tanam, Kaku, Akarmatrik notations. Unit-II Folk Music Origin, evolution and classification of Indian folk song / music. Characteristics of folk music. Detailed study of folk music, folk instruments and performers of various regions in India. Ragas and Talas used in folk music Folk fairs & festivals in India. Unit-III Rasa and Aesthetics: Rasa, Principles of Rasa according to Bharata and others. Rasa nishpatti and its application to Indian Classical Music. Bhava and Rasa Rasa in relation to swara, laya, tala, chhanda and lyrics. -

Maheka Mirpuri

Maheka Mirpuri https://www.indiamart.com/maheka-mirpuri/ Designing for the women of style, Maheka manages to combine elegance and creativity with effortless ease. Her immaculate designs and her effervescent creations have made her a name to reckon with. About Us For designer Maheka Mirpuri what started as a passion soon grew to become her profession with the launch of her couture-de-salon, Mumbai’s only “By Appointment” fashion atelier. Maheka Mirpuri fashioned her alcove in the scintillating world of haute couture by creating spectacular, classy and chic women's wear ensembles. Fashion is something Maheka is passionate about - the most exhilarating way of propagating her experiences, enthusiasm and reverie with others. A designer of repute, Maheka Mirpuri excels in beautifying a woman naturally, highlighting her personality on an individual level. Catering to the astute fashion enthusiasts including Corporates, socialites and celebrities, Maheka Mirpuri’s ensembles are donned by the crème-de-la-crème of the world. Leading names from Bollywood including Sonakshi Sinha, Parineeti Chopra, Deepika Padukone, Sridevi, Manisha Koirala, Bipasha Basu, Prachi Desai, Lara Dutta, Sushmita Sen, Neha Dhupia, Koena Mitra and others have donned Maheka’s sensuous and chic designs both on and off the ramp. Designing for the women of style, Maheka manages to combine elegance and creativity with effortless ease. Her immaculate designs and her effervescent creations have made her a name to reckon with. The designer's signature is prominent in the silhouettes that are at par with international fashion trends. Maheka defines her lines as being characterized by an attention to detail and to.. -

IFFI 2007–Non-Feature Films

IFFI 2007–Non-Feature Films Abhijit Ghosh-Dastidar The International Film Festival at Goa (November 07) offered beautiful, humane portraits in the non-features section of Indian Panorama. Buddhadeb Das Gupta's ''Naushad Ali—The Melody Continues" (Hindi, colour, 39 mins) is a tribute to Naushad Ali, the legendary music composer from Bombay's film world, and the film landscape of the times. The film commences with Dilip Kumar, the actor, visiting Naushad Ali, admitted in Bombay hospital. Naushad passed away in May 06. An 'alap' song, composed by Naushad and sung by Bade Ghulam Ali, from ''Moghal-e-Azam'', is at the debut of the sound track. The voice over states that Naushad was closely linked to Lucknow, where he was born in December 1919. The camera travels along the lanes and streets of Lucknow, with Moghal monuments in the background. Naushad's father was a munshi in court. Naushad had spent his childhood at his grandmother's house. His uncle, Allam, had a harmonium shop, and soon Naushad found a job in a musical instruments shop. He started watching films from the age of eight at the Royal Cinema hall. He was fascinated by the off screen musicians of silent films. Clips from musical silent films roll by. Babbar Khan coached Naushed on the harmonium. Naushad shifted to Bombay in 1937. He spent nights below a staircase. He joined DN Madhok's film production company, and made music for films like ''Mala'' and ''Prem Nagar'', for which he was paid Rs 300 only for each film. He composed classical music to fit the songs of Shamshad Begum in "Baiju Bawra''. -

Page 7.Qxd (Page 1)

JAMMU | WEDNESDAY | APRIL 28, 2021 JB ENTERTAINMENT JAMMU BULLETIN 7 Aashka Goradia quits showbiz: ‘Would Dhanush film Jagame Thandhiram will rather call it moving on to a different phase’ start streaming on Netflix from this date hanush-starrer ashka Goradia has shocked did that when I took up acting two Jagame Thandhiram fans and television audience decades back, and I gave it my all. will be released on by deciding to quit acting to Right now, yes it’s a tough decision D A Netflix on June 18, the pursue her entrepreneurial dreams. and choices are always tough. I am not Having started her make-up brand a just walking away from a career I built streaming giant announced few years back, the actor wants to from the scratch but also the city, on Tuesday evening. Sharing focus on the same in a bid to take it to memories, relationships — I will miss a new poster of the movie in a new level. Calling it a ‘three year everything but I have always believed which a smiling Dhanush is plan’ as of now, Aashka however calls that you have to stride to make a mark seen sporting shades, Netflix it a ‘moving on’ decision rather than in your career,” she replied with a wrote, “Suruli oda aatatha ‘quitting’. The Maharana Pratap actor smile. paaka naanga ready! Neenga shared, “I don’t think you can give up And if you are wondering what ready ah? something that has been such an would Aashka Goradia miss the most, #JagameThandhiram coming important phase in your life. -

Aspirational Movie List

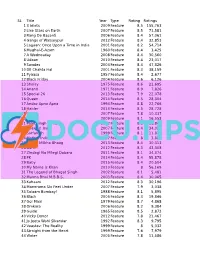

SL Title Year Type Rating Ratings 1 3 Idiots 2009 Feature 8.5 155,763 2 Like Stars on Earth 2007 Feature 8.5 71,581 3 Rang De Basanti 2006 Feature 8.4 57,061 4 Gangs of Wasseypur 2012 Feature 8.4 32,853 5 Lagaan: Once Upon a Time in India 2001 Feature 8.2 54,714 6 Mughal-E-Azam 1960 Feature 8.4 3,425 7 A Wednesday 2008 Feature 8.4 30,560 8 Udaan 2010 Feature 8.4 23,017 9 Swades 2004 Feature 8.4 47,326 10 Dil Chahta Hai 2001 Feature 8.3 38,159 11 Pyaasa 1957 Feature 8.4 2,677 12 Black Friday 2004 Feature 8.6 6,126 13 Sholay 1975 Feature 8.6 21,695 14 Anand 1971 Feature 8.9 7,826 15 Special 26 2013 Feature 7.9 22,078 16 Queen 2014 Feature 8.5 28,304 17 Andaz Apna Apna 1994 Feature 8.8 22,766 18 Haider 2014 Feature 8.5 28,728 19 Guru 2007 Feature 7.8 10,337 20 Dev D 2009 Feature 8.1 16,553 21 Paan Singh Tomar 2012 Feature 8.3 16,849 22 Chakde! India 2007 Feature 8.4 34,024 23 Sarfarosh 1999 Feature 8.1 11,870 24 Mother India 1957 Feature 8 3,882 25 Bhaag Milkha Bhaag 2013 Feature 8.4 30,313 26 Barfi! 2012 Feature 8.3 43,308 27 Zindagi Na Milegi Dobara 2011 Feature 8.1 34,374 28 PK 2014 Feature 8.4 55,878 29 Baby 2015 Feature 8.4 20,504 30 My Name Is Khan 2010 Feature 8 56,169 31 The Legend of Bhagat Singh 2002 Feature 8.1 5,481 32 Munna Bhai M.B.B.S. -

FILM FOKUS EZEBHANYABHANYA Bollywood Comes Alive

FILM FOKUS EZEBHANYABHANYA bollywood comes alive NEVILLE ADONIS DVD Selector, Acquisitions Section that, this being a Yash Raj production, family values will eventually triumph, the fi lm serves up a bonny, bouncing two-and-a-half hours any people confuse the terms of dialogue-driven entertainment. Hollywood and Bollywood. The ‘Khan, who since Hum tum is proving perception is that Bollywood has M to be a real leading man, plays Nikhil ‘Nick’ its origin from Hollywood, but in fact the Arora, a failed architecture student turned only thing the two names have in common chef who is a minor celebrity in Melbourne. is that both have to do with the fi lm industry. Zinta, the most substantial actress among Hollywood is a place and Bollywood is the younger Bollywood group, plays the role Indian cinema. Although Bollywood used to of Ambar Malhotra, a medical student from be mainly shown in India, more and more combines a comedy about Indians Down Bangalore who moonlights at a local radio western countries have shown interest in Under with a dramedy about a yuppie facing station, Salaam Namaste, to pay for her edu- this cinema genre. In my opinion, Bollywood up to fatherhood. With two of the brightest cation. In typical romantic-comedy style, the plots are a little melodramatic with themes of young stars of Hindi cinema, Saif Ali Khan two self-obsessed leads get off on the wrong love-triangles, kidnapping, corrupt politicians and Preity Zinta in Hugh Grant and Julianne foot when Nikhil is late for an interview on and angry parents and, yes, it also features Moore roles, plus the comforting realisation Ambar’s radio show. -

Dil Chahta Hai English Subtitles Download for Movie

Dil Chahta Hai English Subtitles Download For Movie 1 / 4 2 / 4 Dil Chahta Hai English Subtitles Download For Movie 3 / 4 Movie: Dil Chahta Hai with English Subtitles. ... Plz Click Subscribe Button Then Download Your Favorite Video. सब्सक्राईब बटन टच करा आणि तूमचा .... Dil Chahta Hai subtitles. AKA: Do Your Thing, D.C.H.. Welcome to a summer of their lives you will never forget.. Dil Chahta Hai is a 2001 Hindi language film .... BollyNook- BOLLYWOOD Nook- MOVIES SUBTITLES & SONGS lyrics TRANSLATIONS, ... Dil Chahta Hai ... Report Bad Movie Subtitle: Thanks (16). Download.. Dil Chahta Hai 2001 720p BluRay NHD X264 NhaNc3 -- DOWNLOAD c11361aded Download the Bollywood 720p BluRay Music Videos nHD .... Movie details. AKA:Dil Chahta Hai (eng), Do Your Thing (eng) Movie Rating:8.2 / 10 (56136) 183 min [ Welcome to a summer of their lives you will never forget. ] .... Download mp3 songs Koi Khe Khta free from youtube, Koi Khe Khta 3gp clip and mp3 song. ... Koi Kahe Kehta Rahe Full Song | Dil Chahta Hai | Aamir Khan, Akshaye Khanna, Saif Ali Khan. 5:26 Min ... Koi Kahe Kehta Rahe - Dil Chahta Hai (2001) - Karaoke With English Subtitles. 5:43 Min ... Saira Full Movie In Telugu. 6.. Movie details. AKA:Dil Chahta Hai (eng), Do Your Thing (eng) Movie Rating:8.2 / 10 (56136) 183 min [ Welcome to a summer of their lives you will never forget. ] .... Amazon.com: Dil Chahta Hai: Aamir Khan, Akshaye Khanna, Preity Zinta, Sonali ... Sorry, this item is not available in; Image not available; To view this video download Flash Player .... Om Shanti Om Bollywood DVD with English Subtitles ..