Bollywood As National(Ist) Cinema Violence, Patriotism and the National- Popular in Rang De Basanti

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Jodhaa Akbar

JODHAA AKBAR ein Film von Ashutosh Gowariker Indien 2008 ▪ 213 Min. ▪ 35mm ▪ Farbe ▪ OmU KINO START: 22. Mai 2008 www.jodhaaakbar.com polyfilm Verleih Margaretenstrasse 78 1050 Wien Tel.:+43-1-581 39 00-20 www:polyfilm.at [email protected] Pressebetreuung: Allesandra Thiele Tel.:+43-1-581 39 00-14 oder0676-3983813 Credits ...................................................2 Kurzinhalt...............................................3 Pressenotiz ............................................3 Historischer Hintergrund ........................3 Regisseur Ashutosh Gowariker..............4 Komponist A.R. Rahman .......................5 Darsteller ...............................................6 Pressestimmen ......................................9 .......................................................................................Credits JODHAA AKBAR Originaltitel: JODHAA AKBAR Indien 2008 · 213 Minuten · OmU · 35mm · FSK ab 12 beantragt Offizielle Homepage: www.jodhaaakbar.com Regie ................................................Ashutosh Gowariker Drehbuch..........................................Ashutosh Gowariker, Haidar Ali Produzenten .....................................Ronnie Screwvala and Ashutosh Gowariker Musik ................................................A. R. Rahman Lyrics ................................................Javed Akhtar Kamera.............................................Kiiran Deohans Ausführende Produzentin.................Sunita Gowariker Koproduzenten .................................Zarina Mehta, Deven Khote -

Bollywood Lens Syllabus

Bollywood's Lens on Indian Society Professor Anita Weiss INTL 448/548, Spring 2018 [email protected] Mondays, 4-7:20 pm 307 PLC; 541 346-3245 Course Syllabus Film has the ability to project powerful images of a society in ways conventional academic mediums cannot. This is particularly true in learning about India, which is home to the largest film industries in the world. This course explores images of Indian society that emerge through the medium of film. Our attention will be focused on the ways in which Indian society and history is depicted in film, critical social issues being explored through film; the depicted reality vs. the historical reality; and the powerful role of the Indian film industry in affecting social orientations and values. Course Objectives: 1. To gain an awareness of the historical background of the subcontinent and of contemporary Indian society; 2. To understand the sociocultural similarities yet significant diversity within this culture area; 3. To learn about the political and economic realities and challenges facing contemporary India and the rapid social changes the country is experiencing; 4. To learn about the Indian film industry, the largest in the world, and specifically Bollywood. Class format Professor Weiss will open each class with a short lecture on the issues which are raised in the film to be screened for that day. We will then view the selected film, followed by a short break, and then extensive in- class discussion. Given the length of most Bollywood films, we will need to fast-forward through much of the song/dance and/or fighting sequences. -

Representing Bharat Mata in Popular Hindi Films: a Socio-Historical Study of Nationalist Politics of Death

REPRESENTING BHARAT MATA IN POPULAR HINDI FILMS: A SOCIO-HISTORICAL STUDY OF NATIONALIST POLITICS OF DEATH SOUVIK MONDAL Assistant Professor in Sociology. Presidency University, Kolkata, India. E-mail: [email protected] Abstract- Death, which always poses threat to social order with all its uncertainty, can be rationalised teleologically. Historically, Religion has been assigned the role of mitigating the chaotic impact of death by rationalizing it. And if one death is an instance of ‘bad’ death, role of religion has become more essential. With modernity disappears this role of religions and newly emerged scintifico-legal intuitions like state have endeavoured to satiate the rational vacuum created by scientism. In India, during the colonial period the emergence of the image of Mother India or Bharat Mata was a secular attempt to justify the sacrifices of lives of freedom fighters. This article will attempt to analysis the claimed secular nature of Bharat Mata through its illustration from colonial India’s popular culture to its modern day representation in Hindi films. Also, the majoritarian politics of this representation of Bharat Mata as the justifying agent of death would also be analysed to comprehend the constitutional claim of India being a secular nation. I. INTRODUCTION belivable simulation of experiencing first human death state the logical confusion and stuctural aniexty The very idea of death creates an existential confusion associated with the event of death. The cultural of ‘not being’ and almost every single philosophical symbolism of our surroundings also embody the creed's attempt to decode this predicament proves its mysticism and perplexity of death and this universality. -

Fascist Imaginaries and Clandestine Critiques: Young Hindi Film Viewers Respond to Violence, Xenophobia and Love in Cross- Border Romances

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by LSE Research Online Shakuntala Banaji Fascist imaginaries and clandestine critiques: young Hindi film viewers respond to violence, xenophobia and love in cross- border romances Book section Original citation: Banaji, Shakuntala (2007) Fascist imaginaries and clandestine critiques: young Hindi film viewers respond to violence, xenophobia and love in cross-border romances. In: Bharat, Meenakshi and Kumar, Nirmal, (eds.) Filming the line of control: the Indo–Pak relationship through the cinematic lens. Routledge, Oxford, UK. ISBN 9780415460941 © 2007 Routledge This version available at: http://eprints.lse.ac.uk/27360/ Available in LSE Research Online: May 2011 LSE has developed LSE Research Online so that users may access research output of the School. Copyright © and Moral Rights for the papers on this site are retained by the individual authors and/or other copyright owners. Users may download and/or print one copy of any article(s) in LSE Research Online to facilitate their private study or for non-commercial research. You may not engage in further distribution of the material or use it for any profit-making activities or any commercial gain. You may freely distribute the URL (http://eprints.lse.ac.uk) of the LSE Research Online website. This document is the author’s submitted version of the book section. There may be differences between this version and the published version. You are advised to consult the publisher’s version if you wish to cite from it. Fascist imaginaries and clandestine critiques: young Hindi film viewers respond to violence, xenophobia and love in cross-border romances Shakuntala Banaji1 Tarang: I’ve watched Hindi films all my life. -

The Hindu, the Muslim, and the Border In

THE HINDU, THE MUSLIM, AND THE BORDER IN NATIONALIST SOUTH ASIAN CINEMA Vinay Lal University of California, Los Angeles Abstract There is but no question that we can speak about the emergence of the (usually Pakistani or Muslim) ‘terrorist’ figure in many Bollywood films, and likewise there is the indisputable fact of the rise of Hindu nationalism in the political and public sphere. Indian cinema, however, may also be viewed in the backdrop of political developments in Pakistan, where the project of Islamicization can be dated to least the late 1970s and where the turn to a Wahhabi-inspired version of Islam is unmistakable. I argue that the recent history of Pa- kistan must be seen as instigated by a disavowal of the country’s Indic self, and similarly I suggest that scholarly and popular studies of the ‘representation’ of the Muslim in “Bol- lywood” rather too easily assume that such a figure is always the product of caricature and stereotyping. But the border between Pakistan and India, between the self and the other, and the Hindu and the Muslim is rather more porous than we have imagined, and I close with hints at what it means to both retain and subvert the border. Keywords: Border, Communalism, Indian cinema, Nationalism, Pakistan, Partition, Veer-Zaara Resumen 103 Así como el personaje del ‘terrorista’ (generalmente musulmán o paquistaní) está presente en muchos filmes de Bollywood, el nacionalismo hindú está tomando la iniciativa en la esfera política del país. Sin embargo el cine indio también puede hacerse eco de acontecimientos ocurridos en Paquistán, donde desde los años Setenta se ha manifestado un proceso de islamización de la sociedad, con una indudable impronta wahabí. -

A Pedagogical Tool for the Application of Critical Discourse Analysis in the Interpretation of Film and Other Multimodal Discursive Practices

University of Tennessee, Knoxville TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 12-2015 Active Critical Engagement (ACE): A Pedagogical Tool for the Application of Critical Discourse Analysis in the Interpretation of Film and Other Multimodal Discursive Practices Sultana Aaliuah Shabazz University of Tennessee - Knoxville, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_graddiss Part of the Social and Philosophical Foundations of Education Commons Recommended Citation Shabazz, Sultana Aaliuah, "Active Critical Engagement (ACE): A Pedagogical Tool for the Application of Critical Discourse Analysis in the Interpretation of Film and Other Multimodal Discursive Practices. " PhD diss., University of Tennessee, 2015. https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_graddiss/3607 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized administrator of TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a dissertation written by Sultana Aaliuah Shabazz entitled "Active Critical Engagement (ACE): A Pedagogical Tool for the Application of Critical Discourse Analysis in the Interpretation of Film and Other Multimodal Discursive Practices." I have examined the final electronic copy of this dissertation for form and content and recommend that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, with a major in Education. Barbara J. Thayer-Bacon, Major Professor We have read this dissertation and recommend its acceptance: Harry Dahms, Rebecca Klenk, Lois Presser Accepted for the Council: Carolyn R. -

Regional Language Books

March 2011 Regional Language Books BENGALI 1 Banerjee, Mamata Aandolaner katha / Mamata Banerjee.-- Kolkata: Dey's Publishing, 2009. 191p.; 21cm. ISBN : 978-81-295-0922-2. B 080 MAM-aan C68922 2 Ahmed, Afsar Jiban jude prahar / Afsar Ahmed.-- Kolkata: Dey's Publishing, 2009. 192p.; 21cm. ISBN : 978-81-295-0875-1. B 891.443 AHM-j C68920 3 Basu, Nabakumar Achhe se nayantaray / Nabakumar Basu.-- Kolkata: Dey's Publishing, 2009. 184p.; 22cm. ISBN : 978-81-295-0870-6. B 891.443 BAS-ac C68921 4 Chakravarti, Smaranjeet Aamader sei shahore / Smaranjeet Chakrabarti.-- Kolkata: Ananda Publications, 2009. 135p.; 22cm. ISBN : 978-81-7756-778-6. B 891.443 CHA-aam C68784 5 Giri, Bhagyadhar Aranye jhar othe / Bhagyadhar Giri.-- Kolkata: Supreme Publishers, 2008. 152p.; 21cm. B 891.443 GIR-ar C68805 6 Maity, Chittaranjan Nirjane khela / Chittaranjan Maity.-- Kolkata: Dey's Publishing, 2009. 368p.; 24cm. ISBN : 978-81-295-0878-2. B 891.44308 MAI-n C68919 7 Indramitra Nerikutta / Indramitra.-- Kolkata: Karukatha, 2008. 108p.; 22cm. B 891.4431 IND-n C68697 8 Mitra, Premendra Bhoot-shikari mejokarta ebong / Premendra Mitra.-- Kolkata: Dey's Publishing, 2009. 199p.; 24cm. ISBN : 978-81-295-0901-7. B 891.4431 MIT-b C68917 9 Maitra, Swapan Kabi Kishorimohan: jiban-o-kabya / Swapan Maitra.-- Kolkata: Manan Prakashan, 2008. 80p.; 21cm. B 928.9144 KIS-m C68918 GUJARATI 10 Valles, Father Dharmamangal / Father Valles.-- Ahmedabad: Gurjar Grantha Ratna Karyalaya, 2009. 240p.; 21cm. ISBN : 978-81-8480-231-3. G 181.4 P9 B193600 11 Muni Vatsalydeep Jain dharma / Muni Vatsalydeep.-- Ahmedabad: Gurjar Grantharatna Karyalaya, 2008. -

7Th MLA Format Hando

Athens State University Library Using the MLA (Modern Language Association) Format The information here comes from the MLA Handbook for Writers of Research Papers (7th edition). It is always best to consult the Handbook first for any MLA question. If you are using MLA style for a class assignment, it is also a good idea to consult your professor, advisor, librarian, or other campus resources, such as the Writing Center at 256-216-6670, for help with using MLA style. General Format for a Paper The general format for papers written in MLA style is covered in chapter four of the MLA Handbook (pages 115-122). Your paper should be typed, double-spaced on standard-sized white paper (8.5 X 11 inches) with margins of 1 inch on all sides. The pages of your manuscript should be numbered consecutively, beginning with the first page, as part of the manuscript header in the upper right corner of each page. Your references should begin on a separate page from the text of the paper with the title Works Cited centered at the top of the page. Citing Sources in Your Text The question of what must be cited (or documented) in your paper is discussed in chapter 2 of the MLA Handbook, and how you cite sources in the text is covered in chapter 6. When using MLA format, the author's last name and the page number(s) for the information used are given in the text. This points the reader to a complete reference to the source, which appears in the Works Cited list at the end of the paper. -

Melancholia Through Mimesis in Rang De Basanti 1

Melancholia Through Mimesis in Rang De Basanti 1 Journal Title: Wide Screen Vol 1, Issue 2, June 2010 ISSN: 1757-3920 URL: http://widescreenjournal.org Published by Subaltern Media, 17 Holborn Terrace, Woodhouse, Leeds LS6 2QA “BHAGAT SINGH TOPLESS, WAVING IN JEANS”: MELANCHOLIA THROUGH MIMESIS IN RANG DE BASANTI KSHAMA KUMAR ________________________________________________________________________ Abstract: How is history mapped on the topography of twenty first century India? It seems apt to study the idea through modern India’s largest popular culture industry: Bollywood. This paper will examine the interaction between history and modern India in Rang de Basanti/Paint it Yellow (2006). The film employs history to understand the present. This paper, therefore, seeks to understand the different processes by which the film accomplishes this goal.It will involve a detailed study of the melancholia within the film which allows history and the present to co-exist. Temporal and spatial fluidity is afforded in the film through the mimetic process of the meta-drama, which will also then be studied to better understand the melancholic condition. The melancholic and the mimetic in the film, allow for an examination of the socio-political condition that the film seeks to represent. The film, this paper will argue also employs a critique of modern day governance. The paper will thus come full circle and examine modern day politics as a system of political history in action: pre colonial politics in a postcolonial world. _________________________________________________________________________ Rakyesh Omprakash Mehra's Rang de Basanti (Paint it Saffron, 2006), opened, paradoxically for a Bollywood production, not on the pull of its star, Aamir Khan, but the debates spinning off its controversial screenplay. -

Nawazuddin Siddiqui

lifestyle WEDNESDAY, APRIL 1, 2015 Music & Movies Nawazuddin Siddiqui, farmer’s son turned ‘Hindi indie’ star t is a story worthy of a Bollywood plot: The son of a selected for the Cannes Film Festival, he turned heads in cinema hall to watch his films. north Indian farmer, one of nine children, rising to crime thrillers “Kahaani” (Story) and “Talaash” (Search). He will appear again with Salman Khan in upcoming Ibecome the face of independent Hindi cinema. But He said his family are still surprised by how far he has romantic drama “Bajrangi Bhaijaan”, and with Shah Rukh Nawazuddin Siddiqui is still getting used to his success. come. “And you cannot blame them. I am a five-foot six- Khan in “Raees” (Rich Man), in which he plays a cop who “When someone is looking at me, I feel they are looking inch, dark, ordinary-looking man. People didn’t imagine is chasing Khan’s mafia character. Siddiqui says he at someone standing behind me, not at me,” the 40-year- that I would make it,” he said. “It is the mindset of our admires Bollywood megastars for their longevity- old confessed to AFP during an interview at a Mumbai country too, that people like (me) don’t become stars. ”they’re very well-maintained”-and he wouldn’t rule out hotel. Maybe it’s a result of 200 years of colonial rule.” doing a song-and-dance number himself, despite his “I have not got used to it and I won’t allow myself to Industry outsider reservations about Bollywood musicals. -

Aspirational Movie List

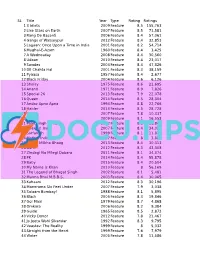

SL Title Year Type Rating Ratings 1 3 Idiots 2009 Feature 8.5 155,763 2 Like Stars on Earth 2007 Feature 8.5 71,581 3 Rang De Basanti 2006 Feature 8.4 57,061 4 Gangs of Wasseypur 2012 Feature 8.4 32,853 5 Lagaan: Once Upon a Time in India 2001 Feature 8.2 54,714 6 Mughal-E-Azam 1960 Feature 8.4 3,425 7 A Wednesday 2008 Feature 8.4 30,560 8 Udaan 2010 Feature 8.4 23,017 9 Swades 2004 Feature 8.4 47,326 10 Dil Chahta Hai 2001 Feature 8.3 38,159 11 Pyaasa 1957 Feature 8.4 2,677 12 Black Friday 2004 Feature 8.6 6,126 13 Sholay 1975 Feature 8.6 21,695 14 Anand 1971 Feature 8.9 7,826 15 Special 26 2013 Feature 7.9 22,078 16 Queen 2014 Feature 8.5 28,304 17 Andaz Apna Apna 1994 Feature 8.8 22,766 18 Haider 2014 Feature 8.5 28,728 19 Guru 2007 Feature 7.8 10,337 20 Dev D 2009 Feature 8.1 16,553 21 Paan Singh Tomar 2012 Feature 8.3 16,849 22 Chakde! India 2007 Feature 8.4 34,024 23 Sarfarosh 1999 Feature 8.1 11,870 24 Mother India 1957 Feature 8 3,882 25 Bhaag Milkha Bhaag 2013 Feature 8.4 30,313 26 Barfi! 2012 Feature 8.3 43,308 27 Zindagi Na Milegi Dobara 2011 Feature 8.1 34,374 28 PK 2014 Feature 8.4 55,878 29 Baby 2015 Feature 8.4 20,504 30 My Name Is Khan 2010 Feature 8 56,169 31 The Legend of Bhagat Singh 2002 Feature 8.1 5,481 32 Munna Bhai M.B.B.S. -

Bio Dillywood 21Pd

164 WEST 25TH ST. SUITE 4F, NEW YORK, NY 10001 USA [email protected] • TEL +1.646.202.9478 • FAX +1.815.550.2861 Dillywood, Inc. is a motion picture production company based in New York that develops and produces film and media projects with a distinctly international focus. Founded in 2004 by producers Anadil Hossain and Driss Benyaklef, the company has been built on their hybrid cultural backgrounds and breadth of experience in film, media, advertising, web content, and large-scale corporate event production. Since then, the company has worked on a gamut of productions in over 25 countries on five continents, establishing long-standing networks in places such as India, U.K., Jordan, Morocco, Kenya, and Hong Kong. The company also has a wide range of experience and know-how working across the US and North America. Dillywood has worked with directors such as Mira Nair (The Namesake, The Reluctant Fundamentalist), Doug Liman (Fair Game), and Wes Anderson (The Darjeeling Limited). Most recently, Dillywood worked on the international segment of Jobs, the biopic of Steve Jobs, starring Ashton Kutcher, and directed by Joshua Stern. The company serves as a creative and logistical bridge between filmmakers and settings, crews, and governments where the films are shot. Dillywood pioneered how large-scale Indian films are shot in the US by producing the US segment of Kal Ho Naa Ho, the first major Indian film to shoot almost entirely in the US. Subsequently, Dillywood worked on the productions of acclaimed directors Karan Johar (Kabhie Alvida Naa Kehna), Rakeysh Mehra (Delhi 6), and with the director of Oscar-nominated Lagaan, Ashutosh Gowariker (Swades, What’s Your Raashee).