Improving the Corrosion Behavior of Ductile Cast Iron in Sulphuric Acid

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Wear Behavior of Austempered and Quenched and Tempered Gray Cast Irons Under Similar Hardness

metals Article Wear Behavior of Austempered and Quenched and Tempered Gray Cast Irons under Similar Hardness 1,2 2 2 2, , Bingxu Wang , Xue Han , Gary C. Barber and Yuming Pan * y 1 Faculty of Mechanical Engineering and Automation, Zhejiang Sci-Tech University, Hangzhou 310018, China; [email protected] 2 Automotive Tribology Center, Department of Mechanical Engineering, School of Engineering and Computer Science, Oakland University, Rochester, MI 48309, USA; [email protected] (X.H.); [email protected] (G.C.B.) * Correspondence: [email protected] Current address: 201 N. Squirrel Rd Apt 1204, Auburn Hills, MI 48326, USA. y Received: 14 November 2019; Accepted: 4 December 2019; Published: 8 December 2019 Abstract: In this research, an austempering heat treatment was applied on gray cast iron using various austempering temperatures ranging from 232 ◦C to 371 ◦C and holding times ranging from 1 min to 120 min. The microstructure and hardness were examined using optical microscopy and a Rockwell hardness tester. Rotational ball-on-disk sliding wear tests were carried out to investigate the wear behavior of austempered gray cast iron samples and to compare with conventional quenched and tempered gray cast iron samples under equivalent hardness. For the austempered samples, it was found that acicular ferrite and carbon saturated austenite were formed in the matrix. The ferritic platelets became coarse when increasing the austempering temperature or extending the holding time. Hardness decreased due to a decreasing amount of martensite in the matrix. In wear tests, austempered gray cast iron samples showed slightly higher wear resistance than quenched and tempered samples under similar hardness while using the austempering temperatures of 232 ◦C, 260 ◦C, 288 ◦C, and 316 ◦C and distinctly better wear resistance while using the austempering temperatures of 343 ◦C and 371 ◦C. -

Effects of Carburization Time and Temperature on the Mechanical Properties of Carburized Mild Steel, Using Activated Carbon As Carburizer

Materials Research, Vol. 12, No. 4, 483-487, 2009 © 2009 Effects of Carburization Time and Temperature on the Mechanical Properties of Carburized Mild Steel, Using Activated Carbon as Carburizer Fatai Olufemi Aramidea,*, Simeon Ademola Ibitoyeb, Isiaka Oluwole Oladelea, Joseph Olatunde Borodea aMetallurgical and Materials Engineering Department, Federal University of Technology, Akure, Ondo State, Nigeria bMaterials Science and Engineering Department, Obafemi Awolowo University, Ile-Ife, Osun State, Nigeria Received: July 31, 2009; Revised: September 25, 2009 Due to the complexity of controlling parameters in carburization, there has been relatively little work on process variables during the surface hardening process. This work focuses on the effects of the carburizing temperature and time on the mechanical properties of mild steel carburized with activated carbon, at 850, 900 and 950 °C, soaked at the carburizing temperature for 15 and 30 minutes, quenched in oil, tempered at 550 °C and held for 60 minutes. Prior carburization process, standard test samples were prepared from the as received specimen for tensile and impact tests. After carburization process, the test samples were subjected to the standard test and from the data obtained, ultimate tensile strength, engineering strain, impact strength, Youngs’ moduli were calculated. The case and core hardness of the carburized tempered samples were measured. It was observed that the mechanical properties of mild steels were found to be strongly influenced by the process of carburization, carburizing temperature and soaking time at carburizing temperature. It was concluded that the optimum combination of mechanical properties is achieved at the carburizing temperature of 900 °C followed by oil quenching and tempering at 550 °C. -

Crucible A2 Data Sheet

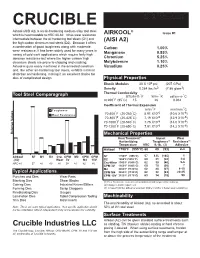

CRUCIBLE DATA SHEET Airkool (AISI A2) is an air-hardening medium alloy tool steel ® Issue #1 which is heat treatable to HRC 60-62. It has wear resistance AIRKOOL intermediate between the oil hardening tool steels (O1) and (AISI A2) the high carbon chromium tool steels (D2). Because it offers a combination of good toughness along with moderate Carbon 1.00% wear resistance, it has been widely used for many years in Manganese 0.85% variety of cold work applications which require fairly high abrasion resistance but where the higher carbon/ high Chromium 5.25% chromium steels are prone to chipping and cracking. Molybdenum 1.10% Airkool is quite easily machined in the annealed condition Vanadium 0.25% and, like other air-hardening tool steels, exhibits minimal distortion on hardening, making it an excellent choice for dies of complicated design. Physical Properties Elastic Modulus 30 X 106 psi (207 GPa) Density 0.284 lbs./in3 (7.86 g/cm3) Thermal Conductivity Tool Steel Comparagraph BTU/hr-ft-°F W/m-°K cal/cm-s-°C at 200°F (95°C) 15 26 0.062 Coefficient of Thermal Expansion ° ° Toughness in/in/ F mm/mm/ C ° ° -6 -6 Wear Resistance 70-500 F (20-260 C) 5.91 X10 (10.6 X10 ) 70-800°F (20-425°C) 7.19 X10-6 (12.9 X10-6) 70-1000°F (20-540°C) 7.76 X10-6 (14.0 X10-6) 70-1200°F (20-650°C) 7.91 X10-6 (14.2 X10-6) Relative Values Mechanical Properties Heat Treatment(1) Impact Wear Austenitizing Toughness(2) Resistance(3) Temperature HRC ft.-lb. -

Electric Furnace Steelmaking

CHAPTER 1.5 Electric Furnace Steelmaking Jorge Madias Metallon, Buenos Aires, Argentina 1.5.1. INTRODUCTION TO ELECTRIC STEELMAKING The history of electric steelmaking is quite short—only little over 100 years from the first trials to melt steel by utilizing electric power. During that period, great advance- ments have been attained both in furnace equipment and technology, melting practice, raw materials, and products. In this chapter, a short introduction to most significant pro- gresses, features, and phenomena in electric steelmaking are presented. 1.5.1.1. Short History of Electric Steelmaking Until Today The electric arc furnace applied in steelmaking was invented in 1889 by Paul He´roult [1]. Emerging new technology started in the beginning of the twentieth century when wide- ranging generation of relatively cheap electric energy started at that time. First-generation furnaces had a capacity in between 1 and 15 t. The EAF had Bessemer/Thomas converters and Siemens Martin furnaces as strong competitors, initially. But its niche was the produc- tion of special steels requiring high temperature, ferroalloy melting, and long refining times. In the 1960s, with the advent of billet casting, the EAF occupied another niche: it was the melting unit of choice for the so-called minimills, feeding billet casters for the pro- duction of rebar and wire rod. In the following two decades, to better support the short tap-to-tap time required by the billet casters, the EAF reinvented itself as a melting-only unit. Steel refining was left for the recently introduced ladle furnace. Large transformers were introduced; ultra- high-power furnaces developed, which were made possible by adopting foaming slag practice. -

The Effect of Tempering on the Microstructure and Mechanical

applied sciences Article The Effect of Tempering on the Microstructure and Mechanical Properties of a Novel 0.4C Press-Hardening Steel Oskari Haiko 1,* , Antti Kaijalainen 1 , Sakari Pallaspuro 1 , Jaakko Hannula 1, David Porter 1, Tommi Liimatainen 2 and Jukka Kömi 1 1 Materials and Mechanical Engineering, Centre for Advanced Steels Research, University of Oulu, 90014 Oulu, Finland; antti.kaijalainen@oulu.fi (A.K.); sakari.pallaspuro@oulu.fi (S.P.); jaakko.hannula@oulu.fi (J.H.); david.porter@oulu.fi (D.P.); jukka.komi@oulu.fi (J.K.) 2 Raahe Works, SSAB Europe, 92100 Raahe, Finland; [email protected] * Correspondence: oskari.haiko@oulu.fi Received: 12 September 2019; Accepted: 4 October 2019; Published: 10 October 2019 Featured Application: Potential wear-resistant steel for harsh environments in agricultural sector, i.e., chisel ploughs and disc harrows. Abstract: In this paper, the effects of different tempering temperatures on a recently developed ultrahigh-strength steel with 0.4 wt.% carbon content were studied. The steel is designed to be used in press-hardening for different wear applications, which require high surface hardness (650 HV/58 HRC). Hot-rolled steel sheet from a hot strip mill was austenitized, water quenched and subjected to 2-h tempering at different temperatures ranging from 150 ◦C to 400 ◦C. Mechanical properties, microstructure, dislocation densities, and fracture surfaces of the steels were characterized. Tensile strength greater than 2200 MPa and hardness above 650 HV/58 HRC were measured for the as-quenched variant. Tempering decreased the tensile strength and hardness, but yield strength increased with low-temperature tempering (150 ◦C and 200 ◦C). -

An Introduction to Nitriding

01_Nitriding.qxd 9/30/03 9:58 AM Page 1 © 2003 ASM International. All Rights Reserved. www.asminternational.org Practical Nitriding and Ferritic Nitrocarburizing (#06950G) CHAPTER 1 An Introduction to Nitriding THE NITRIDING PROCESS, first developed in the early 1900s, con- tinues to play an important role in many industrial applications. Along with the derivative nitrocarburizing process, nitriding often is used in the manufacture of aircraft, bearings, automotive components, textile machin- ery, and turbine generation systems. Though wrapped in a bit of “alchemi- cal mystery,” it remains the simplest of the case hardening techniques. The secret of the nitriding process is that it does not require a phase change from ferrite to austenite, nor does it require a further change from austenite to martensite. In other words, the steel remains in the ferrite phase (or cementite, depending on alloy composition) during the complete proce- dure. This means that the molecular structure of the ferrite (body-centered cubic, or bcc, lattice) does not change its configuration or grow into the face-centered cubic (fcc) lattice characteristic of austenite, as occurs in more conventional methods such as carburizing. Furthermore, because only free cooling takes place, rather than rapid cooling or quenching, no subsequent transformation from austenite to martensite occurs. Again, there is no molecular size change and, more importantly, no dimensional change, only slight growth due to the volumetric change of the steel sur- face caused by the nitrogen diffusion. What can (and does) produce distor- tion are the induced surface stresses being released by the heat of the process, causing movement in the form of twisting and bending. -

BAT Guide for Electric Arc Furnace Iron & Steel Installations

Eşleştirme Projesi TR 08 IB EN 03 IPPC – Entegre Kirlilik Önleme ve Kontrol T.C. Çevre ve Şehircilik Bakanlığı BAT Guide for electric arc furnace iron & steel installations Project TR-2008-IB-EN-03 Mission no: 2.1.4.c.3 Prepared by: Jesús Ángel Ocio Hipólito Bilbao José Luis Gayo Nikolás García Cesar Seoánez Iron & Steel Producers Association Serhat Karadayı (Asil Çelik Sanayi ve Ticaret A.Ş.) Muzaffer Demir Mehmet Yayla Yavuz Yücekutlu Dinçer Karadavut Betül Keskin Çatal Zerrin Leblebici Ece Tok Şaziye Savaş Özlem Gülay Önder Gürpınar October 2012 1 Eşleştirme Projesi TR 08 IB EN 03 IPPC – Entegre Kirlilik Önleme ve Kontrol T.C. Çevre ve Şehircilik Bakanlığı Contents 0 FOREWORD ............................................................................................................................ 12 1 INTRODUCTION. ..................................................................................................................... 14 1.1 IMPLEMENTATION OF THE DIRECTIVE ON INDUSTRIAL EMISSIONS IN THE SECTOR OF STEEL PRODUCTION IN ELECTRIC ARC FURNACE ................................................................................. 14 1.2 OVERVIEW OF THE SITUATION OF THE SECTOR IN TURKEY ...................................................... 14 1.2.1 Current Situation ............................................................................................................ 14 1.2.2 Iron and Steel Production Processes............................................................................... 17 1.2.3 The Role Of Steel Sector in -

187 Gas Nitriding with Deep Cryogenic Treatment Of

Acta Metallurgica Slovaca, Vol. 24, 2018, No. 2, p. 187-193 187 GAS NITRIDING WITH DEEP CRYOGENIC TREATMENT OF HIGH-SPEED STEEL David Hradil1)*, Michal Duchek1), Taťána Hrbáčková1), Aleksander Ciski2) 1) COMTES FHT, Dobřany, Czech Republic 2) Institute of Precision Mechanics, Warsaw, Poland Received: 12.03.2018 Accepted: 28.05.2018 *Corresponding author: e-mail: [email protected], Tel.:+420 377 197 365, COMTES FHT, Průmyslová 995, 334 41 Dobřany, Czech Republic Abstract Nitriding with subsequent heat treatment in combination with deep cryogenic treatment (DCT) produces nitrided layers with specific properties. Layers with unique properties result from the dissolution of subsurface layers of iron nitrides and subsequent nitrogen diffusion into the substrate during austenitisation. Fine precipitates of carbonitrides eventually form during DCT and tempering. Intermediate deep cryogenic treatment was performed between the quenching and tempering steps. This work is based on comparing nitrided layers obtained using conventional treatment parameters with nitrided layers from novel processes. The experimental material was DIN 1.3343 (Czech Standard 41 9830) high-speed steel. Several treatment methods were compared in terms of the resulting hardness and metallographic characteristics. Keywords: Deep Cryogenic Treatment, Nitriding, Metallography, Hardness 1 Introduction Steels are nitrided in the machinery and toolmaking industries to obtain better tribological properties and fatigue performance, which result from compressive stresses generated in the surface [1, 2, 3]. Typical nitrided products include a variety of cutting tools, drills, dies, injection moulds, valves and many machine parts, such as gears, crankshafts and spring [4]. In nitriding, nitrogen is introduced into the surface of steel over a period of several tens of hours. -

Construction Health and Safety Manual: Steel Mills

STEEL MILLS 34 STEEL MILLS some scrap steel. Pure oxygen is blown into the vessel and the resulting reaction generates a lot of carbon monoxide Steelmaking Process during blowing time, which can be burned in a waste heat furnace built into the hood system before the flue gases are The conventional steelmaking process, in its most basic discharged to a precipitator and baghouse system. form, consists of the following sequence of steps. Electric furnaces are used in some facilities to produce Blast furnace ironmaking – Three raw materials (iron stainless steels and in others to produce mild steels. ore, coal, and limestone) are modified, brought together, Electric furnaces are charged primarily with scrap iron and and smelted in a blast furnace to produce iron for sponge-iron pellets or steel scrap which has been analyzed steelmaking. Iron, usually in molten form, is transported in and sorted. hot metal cars to the steelmaking furnaces where Two types of electric furnaces are typically used: impurities are removed and alloying elements are added. 1) the electric arc furnace, generating heat from the arcs Molten steel is then cast (usually using a continuous from one carbon electrode to the metal and back to the casting process ) in large blocks such as slabs, blooms, other carbon electrode from the metal and from the billets, or ingots, which are subsequently reheated, resistance of the current flow through the metal itself, and cleaned, and reshaped repeatedly, and often coated, in a 2) the induction furnace, which behaves like a series of operations to produce the variety of steel transformer, in which the metal acts as the core and products that we know. -

Waste Heat Recovery for EAF — Innovative Concepts and Industrial Implementation

56 Technical Article Waste Heat Recovery for EAF — Innovative Concepts and Industrial Implementation Authors The development of a waste heat recovery plant requires extensive knowledge as well as long A. Fleischanderl experience of the entire plant. Primetals provides waste heat recovery solutions for EAFs, some of technology officer upstream, which are presented in this article. A waste heat recovery plant is introduced, which was installed Primetals Technologies Austria in Italy. Waste heat is used to produce steam for two pickling lines, which are a large distance GmbH, Linz, Austria [email protected] from the EAF. The substitution of the existing gas-fired boilers led to a decisive reduction of operating costs of the steel plant. A heat recovery plant was installed at a steel plant in Sweden, T. Steinparzer where hot water at high pressure is produced and utilized for the local district heating system. head of technology and innovation ECO solutions, Primetals The implementation of waste heat recovery systems for EAFs will be presented in detail, and Technologies Austria GmbH, operational results achieved will be discussed. Linz, Austria [email protected] P. Trunner n recent years, waste heat recov- decreased and the global steel indus- process engineer waste heat ery in the steel industry has try is dealing with overproduction. recovery, Primetals Technologies I Austria GmbH, Linz, Austria attracted more and more attention. Therefore, steel plant operators are [email protected] Environmental regulations, public forced to reduce production costs funding, as well as required revamps and to optimize their steelmaking of old dedusting systems lead steel processes. -

A Novel Decarburizing-Nitriding Treatment of Carburized/Through-Hardened Bearing Steel Towards Enhanced Nitriding Kinetics and Microstructure Refinement

coatings Article A Novel Decarburizing-Nitriding Treatment of Carburized/through-Hardened Bearing Steel towards Enhanced Nitriding Kinetics and Microstructure Refinement Fuyao Yan 1, Jiawei Yao 1, Baofeng Chen 1, Ying Yang 1, Yueming Xu 2, Mufu Yan 1,* and Yanxiang Zhang 1,* 1 School of Materials Science and Engineering, Harbin Institute of Technology, Harbin 150001, China; [email protected] (F.Y.); [email protected] (J.Y.); [email protected] (B.C.); [email protected] (Y.Y.) 2 Beijing Research Institute of Mechanical & Electrical Technology, Beijing 100083, China; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] (M.Y.); [email protected] (Y.Z.); Tel.: +86-451-86418617 (M.Y.) Abstract: Decarburization is generally avoided as it is reckoned to be a process detrimental to material surface properties. Based on the idea of duplex surface engineering, i.e., nitriding the case-hardened or through-hardened bearing steels for enhanced surface performance, this work deliberately applied decarburization prior to plasma nitriding to cancel the softening effect of decarburizing with nitriding and at the same time to significantly promote the nitriding kinetics. To manifest the applicability of this innovative duplex process, low-carbon M50NiL and high-carbon M50 bearing steels were adopted in this work. The influence of decarburization on microstructures and growth kinetics of the nitrided layer over the decarburized layer is investigated. The metallographic analysis of the nitrided layer thickness indicates that high carbon content can hinder the growth of the nitrided Citation: Yan, F.; Yao, J.; Chen, B.; layer, but if a short decarburization is applied prior to nitriding, the thickness of the nitrided layer Yang, Y.; Xu, Y.; Yan, M.; Zhang, Y. -

Effect of Tempering Temperature and Time on Strength and Hardness of Ductile Cast Iron

EFFECT OF TEMPERING TEMPERATURE AND TIME ON STRENGTH AND HARDNESS OF DUCTILE CAST IRON This thesis Submitted In Partial Fulfilment of The requirement For the Degree of Master of Technology ( DUAL DEGREE ) In Metallurgical and Materials Engineering By RAVINDRA KUMAR (Roll no. 710MM1165) Under the Guidance of Dr. Sudipta Sen 2015 1 CERTIFICATE This is to certify that the thesis qualified, “Effect of Tempering Temperature and Time on Strength and Hardness of Ductile Cast Iron” submitted by Ravindra Kumar (710MM1165) for requirements Master of Technology degree in metallurgical & Materials Engineering at National Institute of Technology, Rourkela is a genuine work carried out under my guidance and supervision. Dr. Sudipta Sen Associate professor Department of Metallurgical and Materials Engineering National Institute of Technology Rourkela-769008, Odisha 2 ACKNOWLEDGEMENT I would like to express my sincere gratitude to Dr. Sudipta Sen, Department of Metallurgical and Materials Engineering for assigning me the project “Effect of Tempering Temperature and Time on Strength and Hardness of Ductile Cast Iron” His positive behavior and regular guidance made it possible to understand this project better . It is not possible to acknowledge suitable his important contribution of our knowledge and time given selflessly in proceeding with my project work. I have received infinite support and good guidance from him. I am very grateful to our all professors of Metallurgical and materials engineering department. And Mr. Ranjan Kumar Behera, Ph.D. Scholar, and all my Classmate and my M.Tech friends to given excellent support for helping me throughout the project and providing me with lot of information and support as and when I required.