Effects of Carburization Time and Temperature on the Mechanical Properties of Carburized Mild Steel, Using Activated Carbon As Carburizer

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Progress the Business and Technology of Heat Treating ® May/June 2008 • Volume 8, Number 3

An ASM International® HEATPublication TREATING PROGRESS THE BUSINESS AND TECHNOLOGY OF HEAT TREATING ® www.asminternational.org MAY/JUNE 2008 • VOLUME 8, NUMBER 3 HEAT TREATMENT OF LANDING GEAR HEAT TREAT SIMULATION MICROWAVE HEATING SM Aircraft landing gear, such as on this U.S. Navy FA18 fighter jet, must perform under severe loading conditions and in many different environments. HEAT TREATMENT OF LANDING GEAR The heat treatment of rguably, landing gear has Alloys Used perhaps the most stringent The alloys used for landing gear landing gear is a complex requirements for perform- have remained relatively constant operation requiring ance. They must perform over the past several decades. Alloys A under severe loading con- like 300M and HP9-4-30, as well as the precise control of time, ditions and in many different envi- newer alloys AF-1410 and AerMet ronments. They have complex shapes 100, are in use today on commercial temperature, and carbon and thick sections. and military aircraft. Newer alloys like control. Understanding the Alloys used in these applications Ferrium S53, a high-strength stainless must have high strengths between steel alloy, have been proposed for interaction of quenching, 260 to 300 ksi (1,792 to 2,068 MPa) landing gear applications. The typical racking, and distortion and excellent fracture toughness (up chemical compositions of these alloys to100 ksi in.1/2, or 110 MPa×m0.5). are listed in Table 1. contributes to reduced To achieve these design and per- The alloy 300M (Timken Co., distortion and residual formance goals, heat treatments Canton, Ohio; www.timken.com) is have been developed to extract the a low-alloy, vacuum-melted steel of stress. -

Wear Behavior of Austempered and Quenched and Tempered Gray Cast Irons Under Similar Hardness

metals Article Wear Behavior of Austempered and Quenched and Tempered Gray Cast Irons under Similar Hardness 1,2 2 2 2, , Bingxu Wang , Xue Han , Gary C. Barber and Yuming Pan * y 1 Faculty of Mechanical Engineering and Automation, Zhejiang Sci-Tech University, Hangzhou 310018, China; [email protected] 2 Automotive Tribology Center, Department of Mechanical Engineering, School of Engineering and Computer Science, Oakland University, Rochester, MI 48309, USA; [email protected] (X.H.); [email protected] (G.C.B.) * Correspondence: [email protected] Current address: 201 N. Squirrel Rd Apt 1204, Auburn Hills, MI 48326, USA. y Received: 14 November 2019; Accepted: 4 December 2019; Published: 8 December 2019 Abstract: In this research, an austempering heat treatment was applied on gray cast iron using various austempering temperatures ranging from 232 ◦C to 371 ◦C and holding times ranging from 1 min to 120 min. The microstructure and hardness were examined using optical microscopy and a Rockwell hardness tester. Rotational ball-on-disk sliding wear tests were carried out to investigate the wear behavior of austempered gray cast iron samples and to compare with conventional quenched and tempered gray cast iron samples under equivalent hardness. For the austempered samples, it was found that acicular ferrite and carbon saturated austenite were formed in the matrix. The ferritic platelets became coarse when increasing the austempering temperature or extending the holding time. Hardness decreased due to a decreasing amount of martensite in the matrix. In wear tests, austempered gray cast iron samples showed slightly higher wear resistance than quenched and tempered samples under similar hardness while using the austempering temperatures of 232 ◦C, 260 ◦C, 288 ◦C, and 316 ◦C and distinctly better wear resistance while using the austempering temperatures of 343 ◦C and 371 ◦C. -

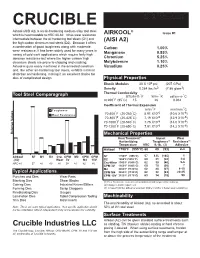

Crucible A2 Data Sheet

CRUCIBLE DATA SHEET Airkool (AISI A2) is an air-hardening medium alloy tool steel ® Issue #1 which is heat treatable to HRC 60-62. It has wear resistance AIRKOOL intermediate between the oil hardening tool steels (O1) and (AISI A2) the high carbon chromium tool steels (D2). Because it offers a combination of good toughness along with moderate Carbon 1.00% wear resistance, it has been widely used for many years in Manganese 0.85% variety of cold work applications which require fairly high abrasion resistance but where the higher carbon/ high Chromium 5.25% chromium steels are prone to chipping and cracking. Molybdenum 1.10% Airkool is quite easily machined in the annealed condition Vanadium 0.25% and, like other air-hardening tool steels, exhibits minimal distortion on hardening, making it an excellent choice for dies of complicated design. Physical Properties Elastic Modulus 30 X 106 psi (207 GPa) Density 0.284 lbs./in3 (7.86 g/cm3) Thermal Conductivity Tool Steel Comparagraph BTU/hr-ft-°F W/m-°K cal/cm-s-°C at 200°F (95°C) 15 26 0.062 Coefficient of Thermal Expansion ° ° Toughness in/in/ F mm/mm/ C ° ° -6 -6 Wear Resistance 70-500 F (20-260 C) 5.91 X10 (10.6 X10 ) 70-800°F (20-425°C) 7.19 X10-6 (12.9 X10-6) 70-1000°F (20-540°C) 7.76 X10-6 (14.0 X10-6) 70-1200°F (20-650°C) 7.91 X10-6 (14.2 X10-6) Relative Values Mechanical Properties Heat Treatment(1) Impact Wear Austenitizing Toughness(2) Resistance(3) Temperature HRC ft.-lb. -

National Register of Historic Places Multiple Property

NFS Form 10-900-b 0MB No. 1024-0018 (Jan. 1987) United States Department of the Interior National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Multipler Propertyr ' Documentation Form NATIONAL This form is for use in documenting multiple property groups relating to one or several historic contexts. See instructions in Guidelines for Completing National Register Forms (National Register Bulletin 16). Complete each item by marking "x" in the appropriate box or by entering the requested information. For additional space use continuation sheets (Form 10-900-a). Type all entries. A. Name of Multiple Property Listing ____Iron and Steel Resources of Pennsylvania, 1716-1945_______________ B. Associated Historic Contexts_____________________________ ~ ___Pennsylvania Iron and Steel Industry. 1716-1945_________________ C. Geographical Data Commonwealth of Pennsylvania continuation sheet D. Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966, as amended, J hereby certify that this documentation form meets the National Register documentation standards and sets forth requirements for the listing of related properties consistent with the National Register criteria. This submission meets the procedural and professional requiremerytS\set forth iri36JCFR PafrfsBOfcyid the Secretary of the Interior's Standards for Planning and Evaluation. Signature of certifying official Date / Brent D. Glass Pennsylvania Historical & Museum Commission State or Federal agency and bureau I, hereby, certify that this multiple -

History of the Hardening of Steel : Science and Technology J

HISTORY OF THE HARDENING OF STEEL : SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY J. Vanpaemel To cite this version: J. Vanpaemel. HISTORY OF THE HARDENING OF STEEL : SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY. Journal de Physique Colloques, 1982, 43 (C4), pp.C4-847-C4-854. 10.1051/jphyscol:19824139. jpa- 00222126 HAL Id: jpa-00222126 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/jpa-00222126 Submitted on 1 Jan 1982 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. JOURNAL DE PHYSIQUE Colloque C4, suppZ4ment au no 12, Tome 43, de'cembre 1982 page C4-847 HISTORY OF THE HARDENING OF STEEL : SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY 3. Vanpaemel Center for historical and socio-economical studies on science and technology Teer EZstZaan 41, 3030 Leuven, SeZgim (Accepted 3 November 1982) Abstract. - The knowledge of the hardening phenomenon was achieved through a very cumulative process without any dis- continuity or 'scientific crisis' . The history of the hardening shows a definite interrelationship between techno- logical approach (or the application-side) and academic science . The hardening of steel appears to have been an operation in common use among the early Greeks The Greek and Roman smiths knew, from experience, how to control the. -

Guide to Non-Ferrous Metals

14 Manufacturing Processes CHAPTER 2 Ferrous Materials and Non-Ferrous Metals and Alloys 2.1 INTRODUCTION Ferrous materials/metals may be defined as those metals whose main constituent is iron such as pig iron, wrought iron, cast iron, steel and their alloys. The principal raw materials for ferrous metals is pig iron. Ferrous materials are usually stronger and harder and are used in daily life products. Ferrous material possess a special property that their characteristics can be altered by heat treatment processes or by addition of small quantity of alloying elements. Ferrous metals possess different physical properties according to their carbon content. 2.2 IRON AND STEEL The ferrous metals are iron base metals which include all varieties of iron and steel. Most common engineering materials are ferrous materials which are alloys of iron. Ferrous means iron. Iron is the name given to pure ferrite Fe, as well as to fused mixtures of this ferrite with large amount of carbon (may be 1.8%), these mixtures are known as pig iron and cast iron. Primarily pig iron is produced from the iron ore in the blast furnace from which cast iron, wrought iron and steel can be produced. 2.3 CLASSIFICATION OF CARBON STEELS Plain carbon steel is that steel in which alloying element is carbon. Practically besides iron and carbon four other alloying elements are always present but their content is very small that they do not affect physical properties. These are sulphur, phosphorus, silicon and manganese. Although the effect of sulphur and phosphorus on properties of steel is detrimental, but their percentage is very small. -

Improving the Corrosion Behavior of Ductile Cast Iron in Sulphuric Acid

Available online at www.pelagiaresearchlibrary.com Pelagia Research Library Der Chemica Sinica, 2017, 8(6):513-523 ISSN : 0976-8505 CODEN (USA): CSHIA5 Improving the Corrosion Behavior of Ductile Cast Iron in Sulphuric Acid by Heat Treatment TFH Mohamed, SS Abd El Rehim and MAM Ibrahim* Chemistry Department, Faculty of Science, Ain Shams University, Abbassia, Cairo, Egypt ABSTRACT In this investigation, the effect of heat treatment on the corrosion behavior of ductile cast iron (DCI) in H2SO4 environment has been conducted. Moreover, the effect of heat treatment on the mechanical properties has also been investigated. The change in microstructure of DCI is obtained by austenetising at 900°C for two hours followed by oil quenching and then heated to 700ºC for different tempering times. The corrosion measurements were tested using anodic potentiodynamic polarization and cyclic polarization techniques. Here we show that the tempered specimens at different tempering times show better corrosion resistance in H2SO4 solution than that without heat treatment. Moreover, the polarization measurements showed that the Ecorr and ia of the different specimens increase with increasing H2SO4 concentration while both Epass and ipass were decreased. Keywords: Ductile cast iron, Corrosion behaviour, Potentiodynamic, Cyclic polarization, Heat treatment INTRODUCTION Ductile cast iron (DCI) possesses several engineering and manufacturing advantages when compared with cast steels [1,2]. These include an excellent damping capacity, better wear resistance, 20-40% lower manufacturing cost and lower volume shrinkage during solidification [3,4]. The combination between the good mechanical properties and the casting abilities of DCI makes its usage successful in structural applications especially in the automotive industry. -

Electric Furnace Steelmaking

CHAPTER 1.5 Electric Furnace Steelmaking Jorge Madias Metallon, Buenos Aires, Argentina 1.5.1. INTRODUCTION TO ELECTRIC STEELMAKING The history of electric steelmaking is quite short—only little over 100 years from the first trials to melt steel by utilizing electric power. During that period, great advance- ments have been attained both in furnace equipment and technology, melting practice, raw materials, and products. In this chapter, a short introduction to most significant pro- gresses, features, and phenomena in electric steelmaking are presented. 1.5.1.1. Short History of Electric Steelmaking Until Today The electric arc furnace applied in steelmaking was invented in 1889 by Paul He´roult [1]. Emerging new technology started in the beginning of the twentieth century when wide- ranging generation of relatively cheap electric energy started at that time. First-generation furnaces had a capacity in between 1 and 15 t. The EAF had Bessemer/Thomas converters and Siemens Martin furnaces as strong competitors, initially. But its niche was the produc- tion of special steels requiring high temperature, ferroalloy melting, and long refining times. In the 1960s, with the advent of billet casting, the EAF occupied another niche: it was the melting unit of choice for the so-called minimills, feeding billet casters for the pro- duction of rebar and wire rod. In the following two decades, to better support the short tap-to-tap time required by the billet casters, the EAF reinvented itself as a melting-only unit. Steel refining was left for the recently introduced ladle furnace. Large transformers were introduced; ultra- high-power furnaces developed, which were made possible by adopting foaming slag practice. -

The Stainless Steel Family

The Stainless Steel Family A short description of the various grades of stainless steel and how they fit into distinct metallurgical families. It has been written primarily from a European perspective and may not fully reflect the practice in other regions. Stainless steel is the term used to describe an extremely versatile family of engineering materials, which are selected primarily for their corrosion and heat resistant properties. All stainless steels contain principally iron and a minimum of 10.5% chromium. At this level, chromium reacts with oxygen and moisture in the environment to form a protective, adherent and coherent, oxide film that envelops the entire surface of the material. This oxide film (known as the passive or boundary layer) is very thin (2-3 namometres). [1nanometre = 10-9 m]. The passive layer on stainless steels exhibits a truly remarkable property: when damaged (e.g. abraded), it self-repairs as chromium in the steel reacts rapidly with oxygen and moisture in the environment to reform the oxide layer. Increasing the chromium content beyond the minimum of 10.5% confers still greater corrosion resistance. Corrosion resistance may be further improved, and a wide range of properties provided, by the addition of 8% or more nickel. The addition of molybdenum further increases corrosion resistance (in particular, resistance to pitting corrosion), while nitrogen increases mechanical strength and enhances resistance to pitting. Categories of Stainless Steels The stainless steel family tree has several branches, which may be differentiated in a variety of ways e.g. in terms of their areas of application, by the alloying elements used in their production, or, perhaps the most accurate way, by the metallurgical phases present in their microscopic structures: . -

The Effect of Tempering on the Microstructure and Mechanical

applied sciences Article The Effect of Tempering on the Microstructure and Mechanical Properties of a Novel 0.4C Press-Hardening Steel Oskari Haiko 1,* , Antti Kaijalainen 1 , Sakari Pallaspuro 1 , Jaakko Hannula 1, David Porter 1, Tommi Liimatainen 2 and Jukka Kömi 1 1 Materials and Mechanical Engineering, Centre for Advanced Steels Research, University of Oulu, 90014 Oulu, Finland; antti.kaijalainen@oulu.fi (A.K.); sakari.pallaspuro@oulu.fi (S.P.); jaakko.hannula@oulu.fi (J.H.); david.porter@oulu.fi (D.P.); jukka.komi@oulu.fi (J.K.) 2 Raahe Works, SSAB Europe, 92100 Raahe, Finland; [email protected] * Correspondence: oskari.haiko@oulu.fi Received: 12 September 2019; Accepted: 4 October 2019; Published: 10 October 2019 Featured Application: Potential wear-resistant steel for harsh environments in agricultural sector, i.e., chisel ploughs and disc harrows. Abstract: In this paper, the effects of different tempering temperatures on a recently developed ultrahigh-strength steel with 0.4 wt.% carbon content were studied. The steel is designed to be used in press-hardening for different wear applications, which require high surface hardness (650 HV/58 HRC). Hot-rolled steel sheet from a hot strip mill was austenitized, water quenched and subjected to 2-h tempering at different temperatures ranging from 150 ◦C to 400 ◦C. Mechanical properties, microstructure, dislocation densities, and fracture surfaces of the steels were characterized. Tensile strength greater than 2200 MPa and hardness above 650 HV/58 HRC were measured for the as-quenched variant. Tempering decreased the tensile strength and hardness, but yield strength increased with low-temperature tempering (150 ◦C and 200 ◦C). -

An Introduction to Nitriding

01_Nitriding.qxd 9/30/03 9:58 AM Page 1 © 2003 ASM International. All Rights Reserved. www.asminternational.org Practical Nitriding and Ferritic Nitrocarburizing (#06950G) CHAPTER 1 An Introduction to Nitriding THE NITRIDING PROCESS, first developed in the early 1900s, con- tinues to play an important role in many industrial applications. Along with the derivative nitrocarburizing process, nitriding often is used in the manufacture of aircraft, bearings, automotive components, textile machin- ery, and turbine generation systems. Though wrapped in a bit of “alchemi- cal mystery,” it remains the simplest of the case hardening techniques. The secret of the nitriding process is that it does not require a phase change from ferrite to austenite, nor does it require a further change from austenite to martensite. In other words, the steel remains in the ferrite phase (or cementite, depending on alloy composition) during the complete proce- dure. This means that the molecular structure of the ferrite (body-centered cubic, or bcc, lattice) does not change its configuration or grow into the face-centered cubic (fcc) lattice characteristic of austenite, as occurs in more conventional methods such as carburizing. Furthermore, because only free cooling takes place, rather than rapid cooling or quenching, no subsequent transformation from austenite to martensite occurs. Again, there is no molecular size change and, more importantly, no dimensional change, only slight growth due to the volumetric change of the steel sur- face caused by the nitrogen diffusion. What can (and does) produce distor- tion are the induced surface stresses being released by the heat of the process, causing movement in the form of twisting and bending. -

Vacuum Systems and Technologies

ALD Vacuum Technologies High Tech is our Business Vacuum Systems and Technologies for Metallurgy and Heat Treatment MetaCom / Product Overview / 09.16 Overview / Product MetaCom Worldwide Leading Our Market Position ALD Vacuum Technologies is a market leader in vacuum systems and process services for thermal and thermo-chemical treatment of solid and molten metals. Our Process and Equipment Portfolio Our engineering expertise includes O vacuum process technology O know-how to design customized system solutions for Vacuum Metallurgy Vacuum Heat Treatment and Sintering Nuclear Fuel Production and Waste Management Vacuum Metallurgy Vacuum metallurgy involves vacuum processes for treating molten metals such as melting and remelting, casting and metal-powder technology as well as specialized vacuum coating technologies for high temperature turbine components. Casting and Coating O Vacuum Induction Melting – Investment Casting (VIM-IC) O Cold-Wall Induction Melting and Casting (LEICOMELT) O VAR Skull Melting and Casting (VAR-SM) Applications System Portfolio O Vacuum Turbine Blade Coating (EB/PVD) Examples of products that were developed ALD offers modern, efficiently Photovoltaic using ALD‘s advaced vacuum processes functioning production systems which O Solar silicon melting and include O significantly contributes to the Crystallization Unit (SCU) O highly alloyed special steels and cost-effectiveness of a high quality Powder Atomization superalloys production O Vacuum Induction Melting Gas O refractory and reactive metals with O covers the