The Effect of Tempering on the Microstructure and Mechanical

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Wear Behavior of Austempered and Quenched and Tempered Gray Cast Irons Under Similar Hardness

metals Article Wear Behavior of Austempered and Quenched and Tempered Gray Cast Irons under Similar Hardness 1,2 2 2 2, , Bingxu Wang , Xue Han , Gary C. Barber and Yuming Pan * y 1 Faculty of Mechanical Engineering and Automation, Zhejiang Sci-Tech University, Hangzhou 310018, China; [email protected] 2 Automotive Tribology Center, Department of Mechanical Engineering, School of Engineering and Computer Science, Oakland University, Rochester, MI 48309, USA; [email protected] (X.H.); [email protected] (G.C.B.) * Correspondence: [email protected] Current address: 201 N. Squirrel Rd Apt 1204, Auburn Hills, MI 48326, USA. y Received: 14 November 2019; Accepted: 4 December 2019; Published: 8 December 2019 Abstract: In this research, an austempering heat treatment was applied on gray cast iron using various austempering temperatures ranging from 232 ◦C to 371 ◦C and holding times ranging from 1 min to 120 min. The microstructure and hardness were examined using optical microscopy and a Rockwell hardness tester. Rotational ball-on-disk sliding wear tests were carried out to investigate the wear behavior of austempered gray cast iron samples and to compare with conventional quenched and tempered gray cast iron samples under equivalent hardness. For the austempered samples, it was found that acicular ferrite and carbon saturated austenite were formed in the matrix. The ferritic platelets became coarse when increasing the austempering temperature or extending the holding time. Hardness decreased due to a decreasing amount of martensite in the matrix. In wear tests, austempered gray cast iron samples showed slightly higher wear resistance than quenched and tempered samples under similar hardness while using the austempering temperatures of 232 ◦C, 260 ◦C, 288 ◦C, and 316 ◦C and distinctly better wear resistance while using the austempering temperatures of 343 ◦C and 371 ◦C. -

Effects of Carburization Time and Temperature on the Mechanical Properties of Carburized Mild Steel, Using Activated Carbon As Carburizer

Materials Research, Vol. 12, No. 4, 483-487, 2009 © 2009 Effects of Carburization Time and Temperature on the Mechanical Properties of Carburized Mild Steel, Using Activated Carbon as Carburizer Fatai Olufemi Aramidea,*, Simeon Ademola Ibitoyeb, Isiaka Oluwole Oladelea, Joseph Olatunde Borodea aMetallurgical and Materials Engineering Department, Federal University of Technology, Akure, Ondo State, Nigeria bMaterials Science and Engineering Department, Obafemi Awolowo University, Ile-Ife, Osun State, Nigeria Received: July 31, 2009; Revised: September 25, 2009 Due to the complexity of controlling parameters in carburization, there has been relatively little work on process variables during the surface hardening process. This work focuses on the effects of the carburizing temperature and time on the mechanical properties of mild steel carburized with activated carbon, at 850, 900 and 950 °C, soaked at the carburizing temperature for 15 and 30 minutes, quenched in oil, tempered at 550 °C and held for 60 minutes. Prior carburization process, standard test samples were prepared from the as received specimen for tensile and impact tests. After carburization process, the test samples were subjected to the standard test and from the data obtained, ultimate tensile strength, engineering strain, impact strength, Youngs’ moduli were calculated. The case and core hardness of the carburized tempered samples were measured. It was observed that the mechanical properties of mild steels were found to be strongly influenced by the process of carburization, carburizing temperature and soaking time at carburizing temperature. It was concluded that the optimum combination of mechanical properties is achieved at the carburizing temperature of 900 °C followed by oil quenching and tempering at 550 °C. -

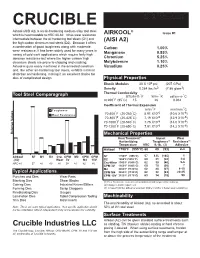

Crucible A2 Data Sheet

CRUCIBLE DATA SHEET Airkool (AISI A2) is an air-hardening medium alloy tool steel ® Issue #1 which is heat treatable to HRC 60-62. It has wear resistance AIRKOOL intermediate between the oil hardening tool steels (O1) and (AISI A2) the high carbon chromium tool steels (D2). Because it offers a combination of good toughness along with moderate Carbon 1.00% wear resistance, it has been widely used for many years in Manganese 0.85% variety of cold work applications which require fairly high abrasion resistance but where the higher carbon/ high Chromium 5.25% chromium steels are prone to chipping and cracking. Molybdenum 1.10% Airkool is quite easily machined in the annealed condition Vanadium 0.25% and, like other air-hardening tool steels, exhibits minimal distortion on hardening, making it an excellent choice for dies of complicated design. Physical Properties Elastic Modulus 30 X 106 psi (207 GPa) Density 0.284 lbs./in3 (7.86 g/cm3) Thermal Conductivity Tool Steel Comparagraph BTU/hr-ft-°F W/m-°K cal/cm-s-°C at 200°F (95°C) 15 26 0.062 Coefficient of Thermal Expansion ° ° Toughness in/in/ F mm/mm/ C ° ° -6 -6 Wear Resistance 70-500 F (20-260 C) 5.91 X10 (10.6 X10 ) 70-800°F (20-425°C) 7.19 X10-6 (12.9 X10-6) 70-1000°F (20-540°C) 7.76 X10-6 (14.0 X10-6) 70-1200°F (20-650°C) 7.91 X10-6 (14.2 X10-6) Relative Values Mechanical Properties Heat Treatment(1) Impact Wear Austenitizing Toughness(2) Resistance(3) Temperature HRC ft.-lb. -

2000 Stainless Steels: an Introduction to Their Metallurgy and Corrosion

Dairy, Food and Environmental Sanitation, Vol. 20, No. 7, Pages 506-517 Copyright© International Association for Food Protection, 6200 Aurora Ave., Suite 200W, Des Moines, IA 50322 Stainless Steels: An Introduction to Their Metallurgy and Corrosion Resistance Roger A. Covert and Arthur H. Tuthill* and why they sometimes do not. In most cases, selection of the proper stainless steel leads to satisfactory performance. COMPOSITION, NOMEN- CLATURE AND GENERAL PROPERTIES Most metals are mixtures of a primary metallic element and one or more intentionally added other ele- This article has been peer-reviewed by two professionals. ments. These mixtures of elements are called alloys. Stainless steels are alloys, as are brasses (copper + zinc), bronzes (copper + tin), the many alu- INTRODUCTION better understanding of stainless minum alloys, and many other me- Worldwide, in industry, in busi- steels, especially to the non-metal- tallic materials. In general, solid ness and in the home, metals called lurgist. metals and alloys consist of randomly stainless steels are used daily. It is Industries are concerned with oriented grains that have a well-de- important to understand what these integrity of equipment and product fined crystalline structure, or lattice, materials are and why they behave purity. To achieve these, stainless within the grains. In stainless steels, the way they do. This is especially steels are often the economical and the crystalline structures within the true because the word “stainless” is practical materials of choice for pro- grains have been given names such as itself somewhat of a misnomer; these cess equipment. However, before ferrite, austenite, martensite, or a materials can stain and can corrode intelligent decisions can be made mixture of two or more of these. -

Preparation and Mechanical Behavior of Ultra-High Strength Low-Carbon Steel

materials Article Preparation and Mechanical Behavior of Ultra-High Strength Low-Carbon Steel Zhiqing Lv 1,2,*, Lihua Qian 1, Shuai Liu 1, Le Zhan 1 and Siji Qin 1 1 Key Laboratory of Advanced Forging & Stamping Technology and Science, Ministry of Education of China Yanshan University, Qinhuangdao 066004, China; [email protected] (L.Q.); [email protected] (S.L.); [email protected] (L.Z.); [email protected] (S.Q.) 2 State Key Laboratory of Metastable Material Science and Technology, Yanshan University, Qinhuangdao 066004, China * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 16 December 2019; Accepted: 14 January 2020; Published: 18 January 2020 Abstract: The low-carbon steel (~0.12 wt%) with complete martensite structure, obtained by quenching, was cold rolled to get the high-strength steel sheets. Then, the mechanical properties of the sheets were measured at different angles to the rolling direction, and the microstructural evolution of low-carbon martensite with cold rolling reduction was observed. The results show that the hardness and the strength gradually increase with increasing rolling reduction, while the elongation and impact toughness obviously decrease. The strength of the sheets with the same rolling reduction are different at the angles of 0◦, 45◦, and 90◦ to the rolling direction. The tensile strength (elongation) along the rolling direction is higher than that in the other two directions, but the differences between them are not obvious. When the aging was performed at a low temperature, the strength of the initial martensite and deformed martensite increased with increasing aging time during the early stages of aging, followed by a gradual decrease with further aging. -

Improving the Corrosion Behavior of Ductile Cast Iron in Sulphuric Acid

Available online at www.pelagiaresearchlibrary.com Pelagia Research Library Der Chemica Sinica, 2017, 8(6):513-523 ISSN : 0976-8505 CODEN (USA): CSHIA5 Improving the Corrosion Behavior of Ductile Cast Iron in Sulphuric Acid by Heat Treatment TFH Mohamed, SS Abd El Rehim and MAM Ibrahim* Chemistry Department, Faculty of Science, Ain Shams University, Abbassia, Cairo, Egypt ABSTRACT In this investigation, the effect of heat treatment on the corrosion behavior of ductile cast iron (DCI) in H2SO4 environment has been conducted. Moreover, the effect of heat treatment on the mechanical properties has also been investigated. The change in microstructure of DCI is obtained by austenetising at 900°C for two hours followed by oil quenching and then heated to 700ºC for different tempering times. The corrosion measurements were tested using anodic potentiodynamic polarization and cyclic polarization techniques. Here we show that the tempered specimens at different tempering times show better corrosion resistance in H2SO4 solution than that without heat treatment. Moreover, the polarization measurements showed that the Ecorr and ia of the different specimens increase with increasing H2SO4 concentration while both Epass and ipass were decreased. Keywords: Ductile cast iron, Corrosion behaviour, Potentiodynamic, Cyclic polarization, Heat treatment INTRODUCTION Ductile cast iron (DCI) possesses several engineering and manufacturing advantages when compared with cast steels [1,2]. These include an excellent damping capacity, better wear resistance, 20-40% lower manufacturing cost and lower volume shrinkage during solidification [3,4]. The combination between the good mechanical properties and the casting abilities of DCI makes its usage successful in structural applications especially in the automotive industry. -

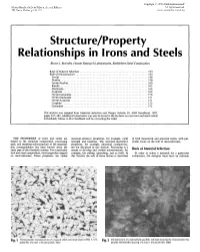

Structure/Property Relationships in Irons and Steels Bruce L

Copyright © 1998 ASM International® Metals Handbook Desk Edition, Second Edition All rights reserved. J.R. Davis, Editor, p 153-173 www.asminternational.org Structure/Property Relationships in Irons and Steels Bruce L. Bramfitt, Homer Research Laboratories, Bethlehem Steel Corporation Basis of Material Selection ............................................... 153 Role of Microstructure .................................................. 155 Ferrite ............................................................. 156 Pearlite ............................................................ 158 Ferrite-Pearl ite ....................................................... 160 Bainite ............................................................ 162 Martensite .................................... ...................... 164 Austenite ........................................................... 169 Ferrite-Cementite ..................................................... 170 Ferrite-Martensite .................................................... 171 Ferrite-Austenite ..................................................... 171 Graphite ........................................................... 172 Cementite .......................................................... 172 This Section was adapted from Materials 5election and Design, Volume 20, ASM Handbook, 1997, pages 357-382. Additional information can also be found in the Sections on cast irons and steels which immediately follow in this Handbook and by consulting the index. THE PROPERTIES of irons and steels -

Chapter 12: Phase Transformations

Chapter 12: Phase Transformations ISSUES TO ADDRESS... • Transforming one phase into another takes time. Fe Fe C Eutectoid 3 γ transformation (cementite) (Austenite) + α C FCC (ferrite) (BCC) • How does the rate of transformation depend on time and temperature ? • Is it possible to slow down transformations so that non-equilibrium structures are formed? • Are the mechanical properties of non-equilibrium structures more desirable than equilibrium ones? AMSE 205 Spring ‘2016 Chapter 12 - 1 Phase Transformations Nucleation – nuclei (seeds) act as templates on which crystals grow – for nucleus to form rate of addition of atoms to nucleus must be faster than rate of loss – once nucleated, growth proceeds until equilibrium is attained Driving force to nucleate increases as we increase ΔT – supercooling (eutectic, eutectoid) – superheating (peritectic) Small supercooling slow nucleation rate - few nuclei - large crystals Large supercooling rapid nucleation rate - many nuclei - small crystals AMSE 205 Spring ‘2016 Chapter 12 - 2 Solidification: Nucleation Types • Homogeneous nucleation – nuclei form in the bulk of liquid metal – requires considerable supercooling (typically 80-300 °C) • Heterogeneous nucleation – much easier since stable “nucleating surface” is already present — e.g., mold wall, impurities in liquid phase – only very slight supercooling (0.1-10 °C) AMSE 205 Spring ‘2016 Chapter 12 - 3 Homogeneous Nucleation & Energy Effects Surface Free Energy- destabilizes the nuclei (it takes energy to make an interface) γ = surface tension ΔGT = Total Free Energy = ΔGS + ΔGV Volume (Bulk) Free Energy – stabilizes the nuclei (releases energy) r* = critical nucleus: for r < r* nuclei shrink; for r > r* nuclei grow (to reduce energy) Adapted from Fig.12.2(b), Callister & Rethwisch 9e. -

Electric Furnace Steelmaking

CHAPTER 1.5 Electric Furnace Steelmaking Jorge Madias Metallon, Buenos Aires, Argentina 1.5.1. INTRODUCTION TO ELECTRIC STEELMAKING The history of electric steelmaking is quite short—only little over 100 years from the first trials to melt steel by utilizing electric power. During that period, great advance- ments have been attained both in furnace equipment and technology, melting practice, raw materials, and products. In this chapter, a short introduction to most significant pro- gresses, features, and phenomena in electric steelmaking are presented. 1.5.1.1. Short History of Electric Steelmaking Until Today The electric arc furnace applied in steelmaking was invented in 1889 by Paul He´roult [1]. Emerging new technology started in the beginning of the twentieth century when wide- ranging generation of relatively cheap electric energy started at that time. First-generation furnaces had a capacity in between 1 and 15 t. The EAF had Bessemer/Thomas converters and Siemens Martin furnaces as strong competitors, initially. But its niche was the produc- tion of special steels requiring high temperature, ferroalloy melting, and long refining times. In the 1960s, with the advent of billet casting, the EAF occupied another niche: it was the melting unit of choice for the so-called minimills, feeding billet casters for the pro- duction of rebar and wire rod. In the following two decades, to better support the short tap-to-tap time required by the billet casters, the EAF reinvented itself as a melting-only unit. Steel refining was left for the recently introduced ladle furnace. Large transformers were introduced; ultra- high-power furnaces developed, which were made possible by adopting foaming slag practice. -

An Introduction to Nitriding

01_Nitriding.qxd 9/30/03 9:58 AM Page 1 © 2003 ASM International. All Rights Reserved. www.asminternational.org Practical Nitriding and Ferritic Nitrocarburizing (#06950G) CHAPTER 1 An Introduction to Nitriding THE NITRIDING PROCESS, first developed in the early 1900s, con- tinues to play an important role in many industrial applications. Along with the derivative nitrocarburizing process, nitriding often is used in the manufacture of aircraft, bearings, automotive components, textile machin- ery, and turbine generation systems. Though wrapped in a bit of “alchemi- cal mystery,” it remains the simplest of the case hardening techniques. The secret of the nitriding process is that it does not require a phase change from ferrite to austenite, nor does it require a further change from austenite to martensite. In other words, the steel remains in the ferrite phase (or cementite, depending on alloy composition) during the complete proce- dure. This means that the molecular structure of the ferrite (body-centered cubic, or bcc, lattice) does not change its configuration or grow into the face-centered cubic (fcc) lattice characteristic of austenite, as occurs in more conventional methods such as carburizing. Furthermore, because only free cooling takes place, rather than rapid cooling or quenching, no subsequent transformation from austenite to martensite occurs. Again, there is no molecular size change and, more importantly, no dimensional change, only slight growth due to the volumetric change of the steel sur- face caused by the nitrogen diffusion. What can (and does) produce distor- tion are the induced surface stresses being released by the heat of the process, causing movement in the form of twisting and bending. -

The Role of Alloying Elements on the Fabricability of Austenitic Stainless Steel

The Role of Alloying Elements on the Fabricability of Austenitic Stainless Steel John C. Tverberg, P.E. Metals and Materials Consulting Engineers Mukwonago, Wisconsin How many times have fabrication problems developed when a new coil or a new heat of steel is put in production? The problems can be tearing, cracking, scratching, poorer weld penetration, poor electropolished surface or a host of other problems. The usual procedure to determine the source of the problem is a hardness test, tensile test, and metallographic cross section and to review the mill test reports. Sometimes the source of the problem is spotted, but most often nothing out of the ordinary is found. In these cases the problem lies in the composition of the steel even when the alloy is within the specified composition of the steel. Alloy Design Austenitic stainless steels are designed to give corrosion resistance in many environments, resistance to hydrogen and 885º F (475º C) embrittlement, good strength, good ductility and low hardness. In its simplest form stainless steel is iron with 12% minimum chromium. This is what makes stainless steel rust resistant and allows the passive film to develop. Stainless steel exists in three metallurgical conditions depending on composition and heat treatment: ferritic, martensitic and austenitic. These names refer to the crystallographic structure: ferrite is body-centered cubic, austenite is face-centered cubic and martensite is a distorted tetragonal which is the distorted face-centered cubic structure being changed into a body-centered structure. The characteristics of these structures are tabulated in Table I and are illustrated in Figure 1. -

BAT Guide for Electric Arc Furnace Iron & Steel Installations

Eşleştirme Projesi TR 08 IB EN 03 IPPC – Entegre Kirlilik Önleme ve Kontrol T.C. Çevre ve Şehircilik Bakanlığı BAT Guide for electric arc furnace iron & steel installations Project TR-2008-IB-EN-03 Mission no: 2.1.4.c.3 Prepared by: Jesús Ángel Ocio Hipólito Bilbao José Luis Gayo Nikolás García Cesar Seoánez Iron & Steel Producers Association Serhat Karadayı (Asil Çelik Sanayi ve Ticaret A.Ş.) Muzaffer Demir Mehmet Yayla Yavuz Yücekutlu Dinçer Karadavut Betül Keskin Çatal Zerrin Leblebici Ece Tok Şaziye Savaş Özlem Gülay Önder Gürpınar October 2012 1 Eşleştirme Projesi TR 08 IB EN 03 IPPC – Entegre Kirlilik Önleme ve Kontrol T.C. Çevre ve Şehircilik Bakanlığı Contents 0 FOREWORD ............................................................................................................................ 12 1 INTRODUCTION. ..................................................................................................................... 14 1.1 IMPLEMENTATION OF THE DIRECTIVE ON INDUSTRIAL EMISSIONS IN THE SECTOR OF STEEL PRODUCTION IN ELECTRIC ARC FURNACE ................................................................................. 14 1.2 OVERVIEW OF THE SITUATION OF THE SECTOR IN TURKEY ...................................................... 14 1.2.1 Current Situation ............................................................................................................ 14 1.2.2 Iron and Steel Production Processes............................................................................... 17 1.2.3 The Role Of Steel Sector in