Scientific Contributions

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

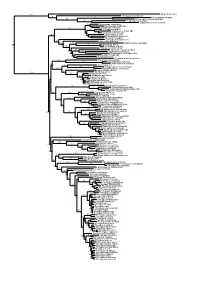

Figs1 ML Tree.Pdf

100 Megaderma lyra Rhinopoma hardwickei 71 100 Rhinolophus creaghi 100 Rhinolophus ferrumequinum 100 Hipposideros armiger Hipposideros commersoni 99 Megaerops ecaudatus 85 Megaerops niphanae 100 Megaerops kusnotoi 100 Cynopterus sphinx 98 Cynopterus horsfieldii 69 Cynopterus brachyotis 94 50 Ptenochirus minor 86 Ptenochirus wetmorei Ptenochirus jagori Dyacopterus spadiceus 99 Sphaerias blanfordi 99 97 Balionycteris maculata 100 Aethalops alecto 99 Aethalops aequalis Thoopterus nigrescens 97 Alionycteris paucidentata 33 99 Haplonycteris fischeri 29 Otopteropus cartilagonodus Latidens salimalii 43 88 Penthetor lucasi Chironax melanocephalus 90 Syconycteris australis 100 Macroglossus minimus 34 Macroglossus sobrinus 92 Boneia bidens 100 Harpyionycteris whiteheadi 69 Harpyionycteris celebensis Aproteles bulmerae 51 Dobsonia minor 100 100 80 Dobsonia inermis Dobsonia praedatrix 99 96 14 Dobsonia viridis Dobsonia peronii 47 Dobsonia pannietensis 56 Dobsonia moluccensis 29 Dobsonia anderseni 100 Scotonycteris zenkeri 100 Casinycteris ophiodon 87 Casinycteris campomaanensis Casinycteris argynnis 99 100 Eonycteris spelaea 100 Eonycteris major Eonycteris robusta 100 100 Rousettus amplexicaudatus 94 Rousettus spinalatus 99 Rousettus leschenaultii 100 Rousettus aegyptiacus 77 Rousettus madagascariensis 87 Rousettus obliviosus Stenonycteris lanosus 100 Megaloglossus woermanni 100 91 Megaloglossus azagnyi 22 Myonycteris angolensis 100 87 Myonycteris torquata 61 Myonycteris brachycephala 33 41 Myonycteris leptodon Myonycteris relicta 68 Plerotes anchietae -

Attacked from Above and Below, New Observations of Cooperative and Solitary Predators on Roosting Cave Bats

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/550582; this version posted February 17, 2019. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 International license. Attacked from above and below, new observations of cooperative and solitary predators on roosting cave bats Krizler Cejuela. Tanalgo1, 2, 3, 7*, Dave L. Waldien4, 5, 6, Norma Monfort6, Alice Catherine Hughes1, 3* 1Landscape Ecology Group, Centre for Integrative Conservation, Xishuangbanna Tropical Botanical Garden, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Menglun, Mengla, Yunnan Province 666303, People’s Republic of China 2International College, University of Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing 100049, People’s Republic of China 3Southeast Asia Biodiversity Research Institute, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Menglun, Mengla, Yunnan Province 666303, People’s Republic of China 4Harrison Institute, Bowerwood House, 15 St Botolph’s Road, Sevenoaks, Kent, TN13 3AQ, United Kingdom 5Christopher Newport University, 1 Avenue of the Arts, Newport News, VA 23606, United States of America 6Philippine Bats for Peace Foundation Inc., 5 Ramona Townhomes, Guadalupe Village, Lanang, Davao City 7Department of Biological Sciences, College of Arts and Sciences, University of Southern Mindanao, Kabacan 9407, North Cotabato, the Republic of the Philippines Corresponding authors: ACH ([email protected]) and KCT ([email protected]) Landscape Ecology Group, Centre for Integrative Conservation, Xishuangbanna Tropical Botanical Garden, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Menglun, Mengla, Yunnan Province 666303, People’s Republic of China Abstract Predation of bats in their roosts has previously only been attributed to a limited number of species such as various raptors, owls, and snakes. -

Final Report on the Project

BP Conservation Programme (CLP) 2005 PROJECT NO. 101405 - BRONZE AWARD WINNER ECOLOGY, DISTRIBUTION, STATUS AND PROTECTION OF THREE CONGOLESE FRUIT BATS FINAL REPORT Patrick KIPALU Team Leader Observatoire Congolais pour la Protection de l’Environnement OCPE – ong Kinshasa – Democratic Republic of the Congo E-mail: [email protected] APRIL 2009 1 Table of Content Acknowledgements…………………………………………………………………. p3 I. Project Summary……………………………………………………………….. p4 II. Introduction…………………………………………………………………… p4-p7 III. Materials and Methods ……………………………………………………….. p7-p10 IV. Results per Study Site…………………………………………………………. p10-p15 1. Pointe-Noire ………………………………………………………….. p10-p12 2. Mayumbe Forest /Luki Reserve……………………………………….. p12-p13 3. Zongo Forest…………………………………………………………... p14 4. Mbanza-Ngungu ………………………………………………………. P15 V. General Results ………………………………………………………………p15-p16 VI. Discussions……………………………………………………………………p17-18 VII. Conclusion and Recommendations……………………………………….p 18-p19 VIII. Bibliography………………………………………………………………p20-p21 Acknowledgements 2 The OCPE (Observatoire Congolais pour la Protection de l’Environnement) project team would like to start by expressing our gratefulness and saying thank you to the BP Conservation Program, which has funded the execution of this project. The OCPE also thanks the Van Tienhoven Foundation which provided a further financial support. Without these organisations, execution of the project would not have been possible. We would like to thank specially the BPCP “dream team”: Marianne D. Carter, Robyn Dalzen and our regretted Kate Stoke for their time, advices, expertise and care, which helped us to complete this work, Our special gratitude goes to Dr. Wim Bergmans, who was the hero behind the scene from the conception to the execution of the research work. Without his expertise, advices and network it would had been difficult for the project team to produce any result from this project. -

Index of Handbook of the Mammals of the World. Vol. 9. Bats

Index of Handbook of the Mammals of the World. Vol. 9. Bats A agnella, Kerivoula 901 Anchieta’s Bat 814 aquilus, Glischropus 763 Aba Leaf-nosed Bat 247 aladdin, Pipistrellus pipistrellus 771 Anchieta’s Broad-faced Fruit Bat 94 aquilus, Platyrrhinus 567 Aba Roundleaf Bat 247 alascensis, Myotis lucifugus 927 Anchieta’s Pipistrelle 814 Arabian Barbastelle 861 abae, Hipposideros 247 alaschanicus, Hypsugo 810 anchietae, Plerotes 94 Arabian Horseshoe Bat 296 abae, Rhinolophus fumigatus 290 Alashanian Pipistrelle 810 ancricola, Myotis 957 Arabian Mouse-tailed Bat 164, 170, 176 abbotti, Myotis hasseltii 970 alba, Ectophylla 466, 480, 569 Andaman Horseshoe Bat 314 Arabian Pipistrelle 810 abditum, Megaderma spasma 191 albatus, Myopterus daubentonii 663 Andaman Intermediate Horseshoe Arabian Trident Bat 229 Abo Bat 725, 832 Alberico’s Broad-nosed Bat 565 Bat 321 Arabian Trident Leaf-nosed Bat 229 Abo Butterfly Bat 725, 832 albericoi, Platyrrhinus 565 andamanensis, Rhinolophus 321 arabica, Asellia 229 abramus, Pipistrellus 777 albescens, Myotis 940 Andean Fruit Bat 547 arabicus, Hypsugo 810 abrasus, Cynomops 604, 640 albicollis, Megaerops 64 Andersen’s Bare-backed Fruit Bat 109 arabicus, Rousettus aegyptiacus 87 Abruzzi’s Wrinkle-lipped Bat 645 albipinnis, Taphozous longimanus 353 Andersen’s Flying Fox 158 arabium, Rhinopoma cystops 176 Abyssinian Horseshoe Bat 290 albiventer, Nyctimene 36, 118 Andersen’s Fruit-eating Bat 578 Arafura Large-footed Bat 969 Acerodon albiventris, Noctilio 405, 411 Andersen’s Leaf-nosed Bat 254 Arata Yellow-shouldered Bat 543 Sulawesi 134 albofuscus, Scotoecus 762 Andersen’s Little Fruit-eating Bat 578 Arata-Thomas Yellow-shouldered Talaud 134 alboguttata, Glauconycteris 833 Andersen’s Naked-backed Fruit Bat 109 Bat 543 Acerodon 134 albus, Diclidurus 339, 367 Andersen’s Roundleaf Bat 254 aratathomasi, Sturnira 543 Acerodon mackloti (see A. -

Investigating the Role of Bats in Emerging Zoonoses

12 ISSN 1810-1119 FAO ANIMAL PRODUCTION AND HEALTH manual INVESTIGATING THE ROLE OF BATS IN EMERGING ZOONOSES Balancing ecology, conservation and public health interest Cover photographs: Left: © Jon Epstein. EcoHealth Alliance Center: © Jon Epstein. EcoHealth Alliance Right: © Samuel Castro. Bureau of Animal Industry Philippines 12 FAO ANIMAL PRODUCTION AND HEALTH manual INVESTIGATING THE ROLE OF BATS IN EMERGING ZOONOSES Balancing ecology, conservation and public health interest Edited by Scott H. Newman, Hume Field, Jon Epstein and Carol de Jong FOOD AND AGRICULTURE ORGANIZATION OF THE UNITED NATIONS Rome, 2011 Recommended Citation Food and Agriculture Organisation of the United Nations. 2011. Investigating the role of bats in emerging zoonoses: Balancing ecology, conservation and public health interests. Edited by S.H. Newman, H.E. Field, C.E. de Jong and J.H. Epstein. FAO Animal Production and Health Manual No. 12. Rome. The designations employed and the presentation of material in this information product do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) concerning the legal or development status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The mention of specific companies or products of manufacturers, whether or not these have been patented, does not imply that these have been endorsed or recommended by FAO in preference to others of a similar nature that are not mentioned. The views expressed in this information product are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of FAO. -

Taxonomy and Natural History of the Southeast Asian Fruit-Bat Genus Dyacopterus

Journal of Mammalogy, 88(2):302–318, 2007 TAXONOMY AND NATURAL HISTORY OF THE SOUTHEAST ASIAN FRUIT-BAT GENUS DYACOPTERUS KRISTOFER M. HELGEN,* DIETER KOCK,RAI KRISTIE SALVE C. GOMEZ,NINA R. INGLE, AND MARTUA H. SINAGA Division of Mammals, National Museum of Natural History (NHB 390, MRC 108), Smithsonian Institution, P.O. Box 37012, Washington, D.C. 20013-7012, USA (KMH) Forschungsinstitut Senckenberg, Senckenberganlage 25, Frankfurt, D-60325, Germany (DK) Philippine Eagle Foundation, VAL Learning Village, Ruby Street, Marfori Heights, Davao City, 8000, Philippines (RKSCG) Department of Natural Resources, Cornell University, Ithaca, NY 14853, USA (NRI) Division of Mammals, Field Museum of Natural History, Chicago, IL 60605, USA (NRI) Museum Zoologicum Bogoriense, Jl. Raya Cibinong Km 46, Cibinong 16911, Indonesia (MHS) The pteropodid genus Dyacopterus Andersen, 1912, comprises several medium-sized fruit-bat species endemic to forested areas of Sundaland and the Philippines. Specimens of Dyacopterus are sparsely represented in collections of world museums, which has hindered resolution of species limits within the genus. Based on our studies of most available museum material, we review the infrageneric taxonomy of Dyacopterus using craniometric and other comparisons. In the past, 2 species have been described—D. spadiceus (Thomas, 1890), described from Borneo and later recorded from the Malay Peninsula, and D. brooksi Thomas, 1920, described from Sumatra. These 2 nominal taxa are often recognized as species or conspecific subspecies representing these respective populations. Our examinations instead suggest that both previously described species of Dyacopterus co-occur on the Sunda Shelf—the smaller-skulled D. spadiceus in peninsular Malaysia, Sumatra, and Borneo, and the larger-skulled D. -

PARASITIC on MEGACHIROPTERAN BATS X

Pacific Insects Monograph 28: 213-243 20 June 1971 REVIEW OF THE STREBLIDAE (Diptera) PARASITIC ON MEGACHIROPTERAN BATS x By T. C. Maa2 Abstract. Of the 16 streblid species previously recorded as parasites of the Megachiroptera, only 6 are here considered to be correctly so associated. Five of these 6 species are re-assigned to a new genus and only 1 is retained in the genus Brachytarsina (^Nycteribosca). These 2 genera are each divided into 2 subgenera and their host relationships, distributional patterns and evolutionary trends are discussed. Earlier records of the species are critically reviewed and are incorporated with new data which are based on some 650 specimens. The new taxa described are Megastrebla, n. gen. (type N. gigantea Speiser); Aoroura, n. subgen, (type N. nigriceps Jobling); Psilacris, n. subgen, (type N. longiarista Jobling); M. (A) limbooliati, n. sp. (Malaya, Borneo); M. (M.) gigantea kaluzvawae, n. ssp. (Fergusson I.); M. (M) gigantea salomonis, n. ssp. (Solomon Is.); M. (M) parvior papuae, n. ssp. (New Guinea). Streblid batflies are rarely found on the suborder Megachiroptera, composed of the single family Pteropodidae, whose members are generally referred to as fruit bats. Only 16 species have been recorded on these bats. A closer examination of the pub lished records clearly indicates that 10 of these 16 species (see Appendix II) should not be considered true parasites of the Megachiroptera; available data support the con cept that no streblids normally breed simultaneously on both the Megachiroptera and Microchiroptera, and among the 39 genera of the former suborder, only those which usually roost in partially illuminated caves and rock-crevices serve as normal breeding hosts of Streblidae. -

Article in Press

ARTICLE IN PRESS Please cite this article in press as: Pettigrew JD, et al., Primate-like retinotectal decussation in an echolocating megabat, ROUSET- TUS AEGYPTIACUS, Neuroscience (2008), doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2008.02.019 Neuroscience xx (2008) xxx PRIMATE-LIKE RETINOTECTAL DECUSSATION IN AN ECHOLOCATING MEGABAT, ROUSETTUS AEGYPTIACUS J. D. PETTIGREW,a* B. C. MASEKOb sophisticated, Doppler-shift compensated laryngeal echo- b AND P. R. MANGER location; they have microchromosomes in their karyotype; aQueensland Brain Institute, University of Queensland 4072, Upland and they have a relatively simple brain organization (ex- Road, Brisbane, QLD 4072, Australia cluding the auditory system) resembling that of insecti- bSchool of Anatomical Sciences, Faculty of Health Sciences, Univer- vores (Manger et al., 2001; Maseko and Manger, 2007). In sity of the Witwatersrand, 7 York Road, Parktown, 2193, Johannes- contrast, megabats have no nose leaf or laryngeal echo- burg, Republic of South Africa location, a normal karyotype, a unique papillated retina and a complex brain (Rosa, 1999; Manger and Rosa, Abstract—The current study was designed to reveal the reti- 2005; Maseko et al., 2007) with visual connections akin to notectal pathway in the brain of the echolocating megabat the pattern found otherwise only in primates (Allman 1977; Rousettus aegyptiacus. The retinotectal pathway of other Pettigrew, 1986). Molecular evidence from serum proteins species of megabats shows the primate-like pattern of de- (Schreiber et al., 1994), hemoglobin (Pettigrew et al., cussation in the retina; however, it has been reported that the echolocating Rousettus did not share this feature. To test 1989), alpha-crystallin (Jaworski, 1995) and other proteins this prior result we injected fluorescent dextran tract tracers contradict the DNA evidence that aligns rhinolophoids with into the right (fluororuby) and left (fluoroemerald) superior the very different megabats, as does morphological anal- colliculi of three adult Rousettus. -

List of 28 Orders, 129 Families, 598 Genera and 1121 Species in Mammal Images Library 31 December 2013

What the American Society of Mammalogists has in the images library LIST OF 28 ORDERS, 129 FAMILIES, 598 GENERA AND 1121 SPECIES IN MAMMAL IMAGES LIBRARY 31 DECEMBER 2013 AFROSORICIDA (5 genera, 5 species) – golden moles and tenrecs CHRYSOCHLORIDAE - golden moles Chrysospalax villosus - Rough-haired Golden Mole TENRECIDAE - tenrecs 1. Echinops telfairi - Lesser Hedgehog Tenrec 2. Hemicentetes semispinosus – Lowland Streaked Tenrec 3. Microgale dobsoni - Dobson’s Shrew Tenrec 4. Tenrec ecaudatus – Tailless Tenrec ARTIODACTYLA (83 genera, 142 species) – paraxonic (mostly even-toed) ungulates ANTILOCAPRIDAE - pronghorns Antilocapra americana - Pronghorn BOVIDAE (46 genera) - cattle, sheep, goats, and antelopes 1. Addax nasomaculatus - Addax 2. Aepyceros melampus - Impala 3. Alcelaphus buselaphus - Hartebeest 4. Alcelaphus caama – Red Hartebeest 5. Ammotragus lervia - Barbary Sheep 6. Antidorcas marsupialis - Springbok 7. Antilope cervicapra – Blackbuck 8. Beatragus hunter – Hunter’s Hartebeest 9. Bison bison - American Bison 10. Bison bonasus - European Bison 11. Bos frontalis - Gaur 12. Bos javanicus - Banteng 13. Bos taurus -Auroch 14. Boselaphus tragocamelus - Nilgai 15. Bubalus bubalis - Water Buffalo 16. Bubalus depressicornis - Anoa 17. Bubalus quarlesi - Mountain Anoa 18. Budorcas taxicolor - Takin 19. Capra caucasica - Tur 20. Capra falconeri - Markhor 21. Capra hircus - Goat 22. Capra nubiana – Nubian Ibex 23. Capra pyrenaica – Spanish Ibex 24. Capricornis crispus – Japanese Serow 25. Cephalophus jentinki - Jentink's Duiker 26. Cephalophus natalensis – Red Duiker 1 What the American Society of Mammalogists has in the images library 27. Cephalophus niger – Black Duiker 28. Cephalophus rufilatus – Red-flanked Duiker 29. Cephalophus silvicultor - Yellow-backed Duiker 30. Cephalophus zebra - Zebra Duiker 31. Connochaetes gnou - Black Wildebeest 32. Connochaetes taurinus - Blue Wildebeest 33. Damaliscus korrigum – Topi 34. -

Bats and Fruit Bats at the Kafa Biosphere Reserve

NABU’s Biodiversity Assessment at the Kafa Biosphere Reserve, Ethiopia Bats and fruit bats at the Kafa Biosphere Reserve Ingrid Kaipf, Hartmut Rudolphi and Holger Meinig 206 BATS Highlights ´ This is the first time a systematic bat assessment has been conducted in the Kafa BR. ´ We recorded four fruit bat species, one of which is new for the Kafa BR but not for Ethiopia. ´ We recorded 29 bat species by capture or sound recording. Four bat species are new for the Kafa BR but occur in other parts of Ethiopia. ´ We recorded calls of a new species in the horseshoe bat family for Ethiopia via echolocation. This data needs to be confirmed by capture, because there is a chance it could be a species of Rhinolophus new to science. ´ We suggest two flagship species: the long-haired rousette for the bamboo forest and the hammer-headed fruit bat for the Alemgono Wetland and Gummi River. ´ The bamboo forests had the most bat activity at night, but the Gojeb Wetland had the highest species richness due to its highly diverse habitats. ´ All caves throughout the entire Kafa BR should be protected as bat roosts. ´ It will be necessary to develop an old tree management concept for the biosphere reserve to protect and increase tree roosts for bats. 207 NABU’s Biodiversity Assessment at the Kafa Biosphere Reserve, Ethiopia 1. Introduction Ethiopia has high megabat and microbat diversity, there were no buildings suitable for bats at any of the thanks to its special geographical position between study sites). So far, 70 bat species have been recorded the sub-Saharan region, East Africa and the Arabic in Ethiopia, five of them endemic to Ethiopia. -

Parturition in Geoffroy's Rousette Fruit Bat

Journal of Threatened Taxa | www.threatenedtaxa.org | 26 November 2014 | 6(12): 6502–6514 Parturition in Geoffroy’s Rousette Fruit Bat Communication Rousettus amplexicaudatus Geoffroy, 1810 ISSN 0974-7907 (Online) (Chiroptera: Pteropodidae) in the Philippines ISSN 0974-7893 (Print) Ambre E. Delpopolo 1, Richard E. Sherwin 2, David L. Waldien 3 & Lindsey C. George 4 OPEN ACCESS 1,2,4 Christopher Newport University, Department of Organismal and Environmental Biology, 1 Avenue of the Arts, Newport News, Virginia, 23606-3072, USA 3 Bat Conservation International, 500 Capital of Texas Highway North, Austin, Texas, 78746-3302, USA 1 [email protected] (corresponding author), 2 [email protected], 3 [email protected], 4 [email protected] Abstract: Biologists have an imperfect understanding of the reproductive biology of bats, which is primarily limited to mating systems and development of neonates. Few studies have addressed parturition in bats. Most of these are not contemporary and are based on data obtained from captive animals housed in laboratories. No studies have been conducted to assess the natural parturition process of Geoffroy’s Rousette Fruit BatRousettus amplexicaudatus, a Yinpterochiropteran native to Southeast Asia and the South Pacific. This study provides the first comprehensive description of parturition in this species. It is based on the natural behaviors exhibited in a wild colony of R. amplexicaudatus in the southern Philippines, which were recorded using high definition video cameras. The qualitative birthing model developed in this study, based on data collected from 16 pregnant females, provides new insights into the reproductive biology of this species. Female R. amplexicaudatus give birth while hanging upside-down. -

African Bat Conservation Species Guide to Bats of Malawi P a G E | 1

African Bat Conservation Species Guide to Bats of Malawi P a g e | 1 Pteropodidae Fruit Bats Epomophorus crypturus Peters’s epauletted fruit bat Genus: Epomophorus Family: Pteropodidae Description Epomophorus crypturus is a large bat with a mass of about 100g. The fur is a light sandy-brown and the underparts are slightly paler. Adult males are much larger than the females and may be distinguished by the presence of shoulder epaulettes. These epaulettes are pockets containing long white fur that can be erected to display prominent white shoulder patches. At rest, these patches disappear as the fur is retracted back into the pocket. The ears have a patch of white fur at their base. The muzzle is dog-like. Distribution This species is widespread and abundant in the eastern parts of central and southern Africa. Ecology Diet Epomophorus crypturus feeds on a wide variety of fruit and flowers, with figs apparently being favoured. Reproduction Pregnant females have been recorded throughout most of the year, with a peak in the presence of juveniles in September, suggesting that births mainly occur at the start of the wet season. One or rarely two young are born. Roosting behaviour They roost singly or in small groups in the dense foliage of a large, leafy tree. Status Least concern African Bat Conservation Species Guide to Bats of Malawi P a g e | 2 Epomophorus labiatus Little epauletted fruit bat Genus: Epomophorus Family: Pteropodidae Description Epomophorus labiatus is a medium-sized bat with a light sandy- brown pelage. The underparts are slights paler than the upper parts.