Attacked from Above and Below, New Observations of Cooperative and Solitary Predators on Roosting Cave Bats

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Coordinated Hunting by Cuban Boas

ABC 2017, 4(1):24-29 Animal Behavior and Cognition DOI: 10.12966/abc.02.02.2017 ©Attribution 3.0 Unported (CC BY 3.0) Coordinated Hunting by Cuban Boas Vladimir Dinets1,* 1University of Tennessee, Knoxville, TN *Corresponding author (Email: [email protected]) Citation – Dinets, V. (2017). Coordinated hunting by Cuban boas. Animal Behavior and Cognition, 4(1), 24–29. doi: 10.12966/abc.02.02.2017 Abstract - Coordinated hunting, in which individual predators relate in time and space to each other’s actions, is uncommon in animals, and is often difficult to distinguish from simply hunting in non-coordinated groups, which is much more common. The author tested if Cuban boas (Chilabothrus angulifer) hunting bats in cave passages take into account other boas’ positions when choosing hunting sites, and whether their choices increase hunting efficiency. Snakes arriving to the hunting area were significantly more likely to position themselves in the part of the passage where other snakes were already present, forming a “fence” across the passage and thus more effectively blocking the flight path of the prey, significantly increasing hunting efficiency. This is the first study to test for coordination between hunting reptiles, rather than assume such coordination based on perceived complexity of hunting behavior. Keywords – Boidae, Chilabothrus angulifer, Cooperative hunting, Cuba, Predation, Social behavior Coordinated hunting, in which individual predators relate in time and space to each other’s actions, is uncommon but widespread in animals (Bailey, -

Investigating the Role of Bats in Emerging Zoonoses

12 ISSN 1810-1119 FAO ANIMAL PRODUCTION AND HEALTH manual INVESTIGATING THE ROLE OF BATS IN EMERGING ZOONOSES Balancing ecology, conservation and public health interest Cover photographs: Left: © Jon Epstein. EcoHealth Alliance Center: © Jon Epstein. EcoHealth Alliance Right: © Samuel Castro. Bureau of Animal Industry Philippines 12 FAO ANIMAL PRODUCTION AND HEALTH manual INVESTIGATING THE ROLE OF BATS IN EMERGING ZOONOSES Balancing ecology, conservation and public health interest Edited by Scott H. Newman, Hume Field, Jon Epstein and Carol de Jong FOOD AND AGRICULTURE ORGANIZATION OF THE UNITED NATIONS Rome, 2011 Recommended Citation Food and Agriculture Organisation of the United Nations. 2011. Investigating the role of bats in emerging zoonoses: Balancing ecology, conservation and public health interests. Edited by S.H. Newman, H.E. Field, C.E. de Jong and J.H. Epstein. FAO Animal Production and Health Manual No. 12. Rome. The designations employed and the presentation of material in this information product do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) concerning the legal or development status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The mention of specific companies or products of manufacturers, whether or not these have been patented, does not imply that these have been endorsed or recommended by FAO in preference to others of a similar nature that are not mentioned. The views expressed in this information product are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of FAO. -

2019. Gada Darbības Pārskats

RĪGAS NACIONĀLAIS ZOOLOĢISKAIS DĀRZS 2O19 RĪGAS NACIONĀLAIS ZOOLOĢISKAIS DĀRZS 2019. GADĀ Rīgas zoodārzs atvērts 1912. gada 14. oktobrī. Paš- zā vairojās 15 EEP sugas, t.sk. trīs savvaļā izmirušas glie- reizējā teritorija – 20 ha. mežu partulu sugas. 1992. gadā Rīgas zoodārzs iestājās Eiropas Zoodār- 2019. gada beigās 79 sugas iekļautas Pasaules Sarkana- zu un akvāriju asociācijā – EAZA (European Associa- jā grāmatā kā apdraudētas (kategorijas VU, EN, CR, EW). tion of Zoos and Aquaria). 2019. gadā Rīgas zoodārzā vairojās 18 no tām. 1993. gadā izveidota Rīgas zoodārza filiāle “Cīruļi” Sīkāk par aizsargājamajām sugām zoodārza kolekcijā – Aizputes novada Kalvenes pagastā (pašreizējā terito- 70. lpp. rija – 132 ha). Zoodārzā notiek dzīvnieku uzvedības pētījumi, 2019. gadā sākti ekotoksikoloģiskie pētījumi. Apmeklētāji Sīkāk par pētījumiem zoodārzā – 21. lpp. Apmeklētāju skaits 2019. gadā – 327 403. Sugu saglabāšana un pētījumi dabā Jaunas ekspozīcijas Rīgas zoodārza līdzšinējais svarīgākais ieguldī jums Āfrikas Savannas ekspozīcija. bioloģiskās daudzveidības saglabāšanā ir 1988.– Invazīvo sugu ekspozīcijas – invazīvo bezmugur- 1992. gadā veiktā Eiropas kokvardes populācijas at- kaulnieku un zivju ekspozīcija Akvārijā un šakāļu ekspo - jaunošana Kurzemē. zīcija. 2019. gadā Rīgas zoodārzs uzsāka atjaunotās kokvaržu Sīkāk par būvdarbiem un remontdarbiem 2019. gadā – populācijas monitoringu. Zoodārzs aicināja Latvijas iedzī- 5. lpp. votājus ziņot par kokvaržu atradnēm, un zoodārza speciā- listi veica kokvaržu uzskaiti un ekoloģijas pētījumus. Dzīvnieku kolekcija Sīkāk par kokvaržu projektu – rakstā 51. lpp. 2019. gada 31. decembrī dzīvnieku kolekcijā bija 398 sugu 2314 dzīvnieki. Dzīvnieku rehabilitācija 2019. gadā vairojās 129 sugu dzīvnieki, piedzima vai 2019. gadā zoodārza karantīnā tika uzņemti 48 ne- izšķīlās 540 mazuļi. laimē nokļuvuši savvaļas dzīvnieki, kā arī 86 konfiscēti Sīkāk par dzīvnieku kolekciju – 22. -

Výroční Zpráva

2017 VÝROČNÍ ZPRÁVA Zoologická a botanická zahrada města Plzně / VÝROČNÍ ZPRÁVA 2017 Zoologická a botanická zahrada města Plzně Zoological and Botanical Garden Pilsen/ Annual Report 2017 Provozovatel ZOOLOGICKÁ A BOTANICKÁ ZAHRADA MĚSTA PLZNĚ, příspěvková organizace ZOOLOGICKÁ A BOTANICKÁ ZAHRADA MĚSTA PLZNĚ POD VINICEMI 9, 301 00 PLZEŇ, CZECH REPUBLIC tel.: 00420/378 038 325, fax: 00420/378 038 302 e-mail: [email protected], www.zooplzen.cz Vedení zoo Management Ředitel Ing. Jiří Trávníček Director Ekonom Jiřina Zábranská Economist Provozní náměstek Ing. Radek Martinec Assistent director Vedoucí zoo. oddělení Bc. Tomáš Jirásek Head zoologist Zootechnik Svatopluk Jeřáb Zootechnicist Zoolog Ing. Lenka Václavová Curator of monkeys, carnivores Jan Konáš Curator of reptiles Miroslava Palacká Curator of ungulates Botanický náměstek, zoolog Ing. Tomáš Peš Head botanist, curator of birds, small mammals Botanik Mgr. Václava Pešková Botanist Propagace, PR Mgr. Martin Vobruba Education and PR Sekretariát Alena Voráčková Secretary Privátní veterinář MVDr. Jan Pokorný Veterinary Celkový počet zaměstnanců Total Employees (k 31. 12. 2017) 130 Zřizovatel Plzeň, statutární město, náměstí Republiky 1, Plzeň IČO: 075 370 tel.: 00420/378 031 111 Fotografie: Kateřina Misíková, Jiří Trávníček, Tomáš Peš, Miroslav Volf, Martin Vobruba, Jiřina Pešová, archiv Zoo a BZ, DinoPark, Oživená prehistorie a autoři článků Redakce výroční zprávy: Jiří Trávníček, Martin Vobruba, Tomáš Peš, Alena Voráčková, Kateřina Misíková, Pavel Toman, David Nováček a autoři příspěvků 1 výroční -

Systematics of Quaternary Squamata from Cuba

UNIVERSIDADE DE SÃO PAULO MUSEU DE ZOOLOGIA Ernesto Aranda Pedroso Systematics of Quaternary Squamata from Cuba Sistemática dos Squamata Quaternários de Cuba Corrected version Dissertation presented to the PostGraduate Program of the Museu de Zoologia da Universidade de São Paulo to obtain the degree of Master of Science (Systematics, Animal Taxonomy and Biodiversity) Advisor: Hussam El Dine Zaher Co-Advisor: Luis Manuel Díaz Beltrán São Paulo 2019 Resumo Aranda E. (2019). Sistemática dos Squama do Quaternário de Cuba. (Dissertação de Mestrado). Museu de Zoologia, Universidade de São Paulo, São Paulo. A paleontologia de répteis no Caribe é um tema de grande interesse para entender como a fauna atual da área foi constituída a partir da colonização e extinção dos seus grupos. O maior número de fósseis pertence a Squamata, que vá desde o Eoceno até nossos dias. O registro abrange todas as ilhas das Grandes Antilhas, a maioria das Pequenas Antilhas e as Bahamas. Cuba, a maior ilha das Antilhas, tem um registro fóssil de Squamata relativamente escasso, com 11 espécies conhecidas de 10 localidades, distribuídas no oeste e centro do país. No entanto, existem muitos outros fósseis depositados em coleções biológicas sem identificação que poderiam esclarecer melhor a história de sua fauna de répteis. Um total de 328 fósseis de três coleções paleontológicas foi selecionado para sua análise, a busca de características osteológicas diagnosticas do menor nível taxonômico possível, e compará-los com outros fósseis e espécies recentes. No presente trabalho, o registro fóssil de Squamata é aumentado, tanto em número de espécies quanto em número de localidades. O registro é estendido a praticamente todo o território cubano. -

Taxonomy and Natural History of the Southeast Asian Fruit-Bat Genus Dyacopterus

Journal of Mammalogy, 88(2):302–318, 2007 TAXONOMY AND NATURAL HISTORY OF THE SOUTHEAST ASIAN FRUIT-BAT GENUS DYACOPTERUS KRISTOFER M. HELGEN,* DIETER KOCK,RAI KRISTIE SALVE C. GOMEZ,NINA R. INGLE, AND MARTUA H. SINAGA Division of Mammals, National Museum of Natural History (NHB 390, MRC 108), Smithsonian Institution, P.O. Box 37012, Washington, D.C. 20013-7012, USA (KMH) Forschungsinstitut Senckenberg, Senckenberganlage 25, Frankfurt, D-60325, Germany (DK) Philippine Eagle Foundation, VAL Learning Village, Ruby Street, Marfori Heights, Davao City, 8000, Philippines (RKSCG) Department of Natural Resources, Cornell University, Ithaca, NY 14853, USA (NRI) Division of Mammals, Field Museum of Natural History, Chicago, IL 60605, USA (NRI) Museum Zoologicum Bogoriense, Jl. Raya Cibinong Km 46, Cibinong 16911, Indonesia (MHS) The pteropodid genus Dyacopterus Andersen, 1912, comprises several medium-sized fruit-bat species endemic to forested areas of Sundaland and the Philippines. Specimens of Dyacopterus are sparsely represented in collections of world museums, which has hindered resolution of species limits within the genus. Based on our studies of most available museum material, we review the infrageneric taxonomy of Dyacopterus using craniometric and other comparisons. In the past, 2 species have been described—D. spadiceus (Thomas, 1890), described from Borneo and later recorded from the Malay Peninsula, and D. brooksi Thomas, 1920, described from Sumatra. These 2 nominal taxa are often recognized as species or conspecific subspecies representing these respective populations. Our examinations instead suggest that both previously described species of Dyacopterus co-occur on the Sunda Shelf—the smaller-skulled D. spadiceus in peninsular Malaysia, Sumatra, and Borneo, and the larger-skulled D. -

1 ¡Cuba! Opens at the American Museum of Natural History

Media Inquiries: Kendra Snyder, Department of Communications 212-496-3419, [email protected] www.amnh.org _____________________________________________________________________________________ November 2016 ¡CUBA! OPENS AT THE AMERICAN MUSEUM OF NATURAL HISTORY NEW EXHIBITION EXPLORES THE ISLAND’S RICH BIODIVERSITY AND CULTURE Cuba is a place of exceptional biodiversity and cultural richness, and now a new bilingual exhibition at the American Museum of Natural History will offer visitors fresh insights into this island nation just 94 miles from Florida’s shores. With a close look at Cuba’s unique natural history, including its native species, highly diverse ecosystems, and geology, ¡Cuba! also explores Cuba’s history, traditions, and contemporary Cuban voices to inspire novel perspectives on this dynamic country. ¡Cuba! opens for a weekend of Member previews on Friday, November 18, and will be on view from Monday, November 21, 2016, to August 13, 2017. “American Museum of Natural History scientists have worked in collaboration with colleagues in Cuba for many decades, studying the extraordinary biological diversity and endemism of this island nation,” said Ellen V. Futter, President of the American Museum of Natural History. “We are delighted now to work in collaboration with the National Natural History Museum in Havana in a groundbreaking partnership to present this major exhibition exploring Cuba’s amazing and unique nature and culture, especially at a time when cultural understanding and education are critically important.” Technically an archipelago of more than 4,000 islands and keys, Cuba is the largest island nation in the Caribbean—and one of the region’s most ecologically diverse countries. About 50 percent of its plants and 32 percent of its vertebrate animals are endemic, meaning they are found only on the island. -

PARASITIC on MEGACHIROPTERAN BATS X

Pacific Insects Monograph 28: 213-243 20 June 1971 REVIEW OF THE STREBLIDAE (Diptera) PARASITIC ON MEGACHIROPTERAN BATS x By T. C. Maa2 Abstract. Of the 16 streblid species previously recorded as parasites of the Megachiroptera, only 6 are here considered to be correctly so associated. Five of these 6 species are re-assigned to a new genus and only 1 is retained in the genus Brachytarsina (^Nycteribosca). These 2 genera are each divided into 2 subgenera and their host relationships, distributional patterns and evolutionary trends are discussed. Earlier records of the species are critically reviewed and are incorporated with new data which are based on some 650 specimens. The new taxa described are Megastrebla, n. gen. (type N. gigantea Speiser); Aoroura, n. subgen, (type N. nigriceps Jobling); Psilacris, n. subgen, (type N. longiarista Jobling); M. (A) limbooliati, n. sp. (Malaya, Borneo); M. (M.) gigantea kaluzvawae, n. ssp. (Fergusson I.); M. (M) gigantea salomonis, n. ssp. (Solomon Is.); M. (M) parvior papuae, n. ssp. (New Guinea). Streblid batflies are rarely found on the suborder Megachiroptera, composed of the single family Pteropodidae, whose members are generally referred to as fruit bats. Only 16 species have been recorded on these bats. A closer examination of the pub lished records clearly indicates that 10 of these 16 species (see Appendix II) should not be considered true parasites of the Megachiroptera; available data support the con cept that no streblids normally breed simultaneously on both the Megachiroptera and Microchiroptera, and among the 39 genera of the former suborder, only those which usually roost in partially illuminated caves and rock-crevices serve as normal breeding hosts of Streblidae. -

Article in Press

ARTICLE IN PRESS Please cite this article in press as: Pettigrew JD, et al., Primate-like retinotectal decussation in an echolocating megabat, ROUSET- TUS AEGYPTIACUS, Neuroscience (2008), doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2008.02.019 Neuroscience xx (2008) xxx PRIMATE-LIKE RETINOTECTAL DECUSSATION IN AN ECHOLOCATING MEGABAT, ROUSETTUS AEGYPTIACUS J. D. PETTIGREW,a* B. C. MASEKOb sophisticated, Doppler-shift compensated laryngeal echo- b AND P. R. MANGER location; they have microchromosomes in their karyotype; aQueensland Brain Institute, University of Queensland 4072, Upland and they have a relatively simple brain organization (ex- Road, Brisbane, QLD 4072, Australia cluding the auditory system) resembling that of insecti- bSchool of Anatomical Sciences, Faculty of Health Sciences, Univer- vores (Manger et al., 2001; Maseko and Manger, 2007). In sity of the Witwatersrand, 7 York Road, Parktown, 2193, Johannes- contrast, megabats have no nose leaf or laryngeal echo- burg, Republic of South Africa location, a normal karyotype, a unique papillated retina and a complex brain (Rosa, 1999; Manger and Rosa, Abstract—The current study was designed to reveal the reti- 2005; Maseko et al., 2007) with visual connections akin to notectal pathway in the brain of the echolocating megabat the pattern found otherwise only in primates (Allman 1977; Rousettus aegyptiacus. The retinotectal pathway of other Pettigrew, 1986). Molecular evidence from serum proteins species of megabats shows the primate-like pattern of de- (Schreiber et al., 1994), hemoglobin (Pettigrew et al., cussation in the retina; however, it has been reported that the echolocating Rousettus did not share this feature. To test 1989), alpha-crystallin (Jaworski, 1995) and other proteins this prior result we injected fluorescent dextran tract tracers contradict the DNA evidence that aligns rhinolophoids with into the right (fluororuby) and left (fluoroemerald) superior the very different megabats, as does morphological anal- colliculi of three adult Rousettus. -

DNA-Validated Parthenogenesis: First Case in a Captive Cuban Boa (Chilabothrus Angulifer)

SALAMANDRA 56(1): 83–86 SALAMANDRA 15 February 2020 ISSN 0036–3375 Correspondence German Journal of Herpetology Correspondence DNA-validated parthenogenesis: first case in a captive Cuban boa (Chilabothrus angulifer) Fernanda Seixas1, Francisco Morinha2, Claudia Luis3, Nuno Alvura3 & Maria dos Anjos Pires1 1) Laboratório de Histologia e Anatomia Patológica, Escola de Ciências Agrárias e Veterinárias, CECAV, Quinta de Prados, 5000-801 Vila Real, Portugal 2) Department of Evolutionary Ecology, National Museum of Natural Sciences (MNCN), Spanish National Research Council (CSIC), José Gutiérrez Abascal 2, 28006 Madrid, Spain 3) Zoo da Maia, Rua da Igreja, S/N, 4470-184 Maia, Portugal Corresponding author: Maria dos Anjos Pires, e-mail: [email protected] Manuscript received: 24 September 2019 Accepted: 15 December 2019 by Arne Schulze Parthenogenesis is a natural form of asexual reproduction FP has been reported in various species of major vertebrate in which offspring are produced from unfertilised eggs groups including reptiles, birds and elasmobranchs (sharks (Neaves & Baumann 2011, van der Kooi & Schwander and rays) (Booth & Schuett 2016, Harmon et al. 2016, 2015). This uncommon reproductive strategy has been re- Dudgeon et al. 2017, Ramachandran & McDaniel, ported in less than 0.1% of vertebrate species, neverthe- 2018). Most FP events were documented in captive females less including a wide range of taxa (i.e. fishes, amphibians, after long periods without contact with male conspecifics reptiles, birds and mammals), even in wild populations during their reproductive lifetime (Lampert 2008, Booth (Neaves & Baumann 2011, Booth et al. 2012, van der & Schuett 2016). However, parthenogenesis has recently Kooi & Schwander 2015, Dudgeon et al. -

Bats and Fruit Bats at the Kafa Biosphere Reserve

NABU’s Biodiversity Assessment at the Kafa Biosphere Reserve, Ethiopia Bats and fruit bats at the Kafa Biosphere Reserve Ingrid Kaipf, Hartmut Rudolphi and Holger Meinig 206 BATS Highlights ´ This is the first time a systematic bat assessment has been conducted in the Kafa BR. ´ We recorded four fruit bat species, one of which is new for the Kafa BR but not for Ethiopia. ´ We recorded 29 bat species by capture or sound recording. Four bat species are new for the Kafa BR but occur in other parts of Ethiopia. ´ We recorded calls of a new species in the horseshoe bat family for Ethiopia via echolocation. This data needs to be confirmed by capture, because there is a chance it could be a species of Rhinolophus new to science. ´ We suggest two flagship species: the long-haired rousette for the bamboo forest and the hammer-headed fruit bat for the Alemgono Wetland and Gummi River. ´ The bamboo forests had the most bat activity at night, but the Gojeb Wetland had the highest species richness due to its highly diverse habitats. ´ All caves throughout the entire Kafa BR should be protected as bat roosts. ´ It will be necessary to develop an old tree management concept for the biosphere reserve to protect and increase tree roosts for bats. 207 NABU’s Biodiversity Assessment at the Kafa Biosphere Reserve, Ethiopia 1. Introduction Ethiopia has high megabat and microbat diversity, there were no buildings suitable for bats at any of the thanks to its special geographical position between study sites). So far, 70 bat species have been recorded the sub-Saharan region, East Africa and the Arabic in Ethiopia, five of them endemic to Ethiopia. -

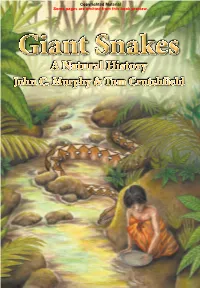

G Iant Snakes

Copyrighted Material Some pages are omitted from this book preview. Giant Snakes Giant Giant Snakes A Natural History John C. Murphy & Tom Crutchfield Snakes, particularly venomous snakes and exceptionally large constricting snakes, have haunted the human brain for a millennium. They appear to be responsible for our excellent vision, as well as the John C. Murphy & Tom Crutchfield & Tom C. Murphy John anxiety we feel. Despite the dangers we faced in prehistory, snakes now hold clues to solving some of humankind’s most debilitating diseases. Pythons and boas are capable of eating prey that is equal to more than their body weight, and their adaptations for this are providing insight into diabetes. Fascination with snakes has also drawn many to keep them as pets, including the largest species. Their popularity in the pet trade has led to these large constrictors inhabiting southern Florida. This book explores what we know about the largest snakes, how they are kept in captivity, and how they have managed to traverse ocean barriers with our help. Copyrighted Material Some pages are omitted from this book preview. Copyrighted Material Some pages are omitted from this book preview. Giant Snakes A Natural History John C. Murphy & Tom Crutchfield Copyrighted Material Some pages are omitted from this book preview. Giant Snakes Copyright © 2019 by John C. Murphy & Tom Cructhfield All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means including information storage and retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the publisher. Printed in the United States of America First Printing March 2019 ISBN 978-1-64516-232-2 Paperback ISBN 978-1-64516-233-9 Hardcover Published by: Book Services www.BookServices.us ii Copyrighted Material Some pages are omitted from this book preview.