Downloads/ Biotope 28032018.Pdf (Accessed on 29 March 2020)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Alto Adige Wines Südtirol Wein Leaf Through

Alto Adige Winesleaf throughSüdtirol Wein Pampered by Mediterranean sun, shaped by the Alpine landscape, prepared by experienced winegrowers, and prized by connoisseurs throughout the world: wine from Alto Adige. Published by: EOS – Export Organization Alto Adige of the Chamber of Commerce of Bolzano Alto Adige Wines – www.altoadigewines.com Concept, Graphics, Text: hannomayr.communication - www.hannomayr.com English Translation: Index Philip Isenberg, MM, CT Pictures: Kellerei Kaltern Caldaro/Hertha Hurnaus Manincor/Archiv BILDRAUM 2004 06 Where the North is Suddenly South 09 The Winegrowing Region of Alto Adige 10 Wine Alois Lageder Tramin/Yoshiko Kusano, Florian Andergassen Cantina Terlano/Udo Bernhart History and Culture 15 Wine and Architecture 20 The Land of Great Wines 22 Terroir 24 Topo- Tenuta Kornell Südtirol Marketing/Stefano Scatà EOS–Alto Adige Wines/F. Blickle, C. Zahn, Suedtirolfoto.com graphy and Climate 26 Geology and Soils 28 The Seven Winegrowing Zones 36 Small Area, Large © All photos are protected by copyright. Map: Variety 38 A Multitude of Varieties 40 The White Wines 47 The Red Wines 51 Niche Varieties Department of Cartography, Autonomous Province of Bolzano – Alto Adige Printing: 52 Cuvées 53 Sparkling Wine 54 “We Cultivate Our Own Style” 57 Cultivation 61 Vinification Longo Spa-Plc, Bolzano Note: Alto Adige’s wine industry is in constant flux. Statistics on vineyard areas 65 Organization and Marketing 66 DOC Classification 69 In the Best Company 71 Wine and production quantities refer to the autumn of 2010. © Copyright 2011. All rights reserved. Pairings 72 Wine Events in Alto Adige 76 Glossary 80 Wineries from A-Z 88 Useful Addresses 618/201102/3000 06 07 Where the North is Suddenly South 08 09 A CH The Winegrowing Bolzano I Region of Alto Adige Alto Adige/Südtirol BETwEEN MouNTaiNs aNd CyPrEssEs Italy Alto Adige/Südtirol lies right in the middle: between Austria and Switzer- land on Italian soil. -

Map 19 Raetia Compiled by H

Map 19 Raetia Compiled by H. Bender, 1997 with the assistance of G. Moosbauer and M. Puhane Introduction The map covers the central Alps at their widest extent, spanning about 160 miles from Cambodunum to Verona. Almost all the notable rivers flow either to the north or east, to the Rhine and Danube respectively, or south to the Po. Only one river, the Aenus (Inn), crosses the entire region from south-west to north-east. A number of large lakes at the foot of the Alps on both its north and south sides played an important role in the development of trade. The climate varies considerably. It ranges from the Mediterranean and temperate to permafrost in the high Alps. On the north side the soil is relatively poor and stony, but in the plain of the R. Padus (Po) there is productive arable land. Under Roman rule, this part of the Alps was opened up by a few central routes, although large numbers of mountain tracks were already in use. The rich mineral and salt deposits, which in prehistoric times had played a major role, became less vital in the Roman period since these resources could now be imported from elsewhere. From a very early stage, however, the Romans showed interest in the high-grade iron from Noricum as well as in Tauern gold; they also appreciated wine and cheese from Raetia, and exploited the timber trade. Ancient geographical sources for the region reflect a growing degree of knowledge, which improves as the Romans advance and consolidate their hold in the north. -

Südtirol Ultra Skyrace 2018, Bozen (I) (51) Sky Marathon (42,2 Km) Männer M1

Datum: 29.07.18 Südtirol Ultra Skyrace 2018, Bozen (I) Zeit: 11:09:43 Seite: 1 (51) Sky Marathon (42,2 km) Männer M1 Rang Name und Vorname Jg Land/Ort Zeit Abstand Overall Stnr 1. Rohringer Daniel 1990 A-Gosau 4:14.38,6 ------ M-Men 1. 2001 Rittner Horn 2:14.52,6 1. 2:14.52,6 1. Sarnthein 1:59.46,0 1. 4:14.38,6 1. 2. Brugger Hansrudi 1980 St.Leonhard in Passeier (BZ) 4:31.10,7 16.32,1 M-Men 2. 2020 Rittner Horn 2:23.32,4 2. 2:23.32,4 2. Sarnthein 2:07.38,3 2. 4:31.10,7 2. 3. Plattner Georg 1995 Molten (BZ) 4:47.48,4 33.09,8 M-Men 4. 2107 Rittner Horn 2:36.07,2 5. 2:36.07,2 5. Sarnthein 2:11.41,2 3. 4:47.48,4 3. 4. Perini Samuel 1986 Bad Rogaz 4:49.21,8 34.43,2 M-Men 5. 2102 Rittner Horn 2:35.36,9 4. 2:35.36,9 4. Sarnthein 2:13.44,9 4. 4:49.21,8 4. 5. Guglielmetti Luca 1983 Cantù (CO) 5:03.42,2 49.03,6 M-Men 8. 2050 Rittner Horn 2:31.56,4 3. 2:31.56,4 3. Sarnthein 2:31.45,8 5. 5:03.42,2 5. 6. Mittich Christian 1986 Platzen (BZ) 5:20.03,7 1:05.25,1 M-Men 11. 2172 Rittner Horn 2:47.58,0 9. -

Gefahrenzonenplanung Piani Delle Zone Di Pericolo

Gefahrenzonenplanung Piani delle Zone di Pericolo Prettau Predoi Ahrntal Valle Aurina Pfitsch Brenner Val di Vizze Sand in Taufers Brennero Campo Tures Sterzing Mühlwald Vipiteno Selva dei Molini Vintl Ratschings Vandoies Racines Freienfeld Terenten Gais Rasen-Antholz Moos in Passeier Mühlbach Campo di Trens Terento Gais Rasun Anterselva Moso in Passiria Rio di Pusteria Pfalzen Gsies Falzes Percha Valle di Casies Kiens Bruneck Perca Brunico Franzensfeste Chienes St.Leonhard in Pass. Graun im Vinschgau Fortezza Rodeneck S.Leonardo in Passiria Rodengo Welsberg-Taisten Curon Venosta St.Lorenzen St.Martin in Passeier Natz-Schabs Monguelfo-Tesido S.Martino in Passiria S.Lorenzo di Sebato Naz-Sciaves Olang Niederdorf Innichen Riffian Valdaora Villabassa S.Candido Rifiano Vahrn Lüsen Varna Luson Tirol Sarntal Toblach Mals Schnals Schenna Brixen Prags Partschins Tirolo Kuens Sarentino Dobbiaco Malles Venosta Senales Scena Bressanone Braies Sexten Parcines Algund Caines Feldthurns Klausen Enneberg Sesto Lagundo Velturno Chiusa Marebbe St.Martin in Thurn Wengen Meran Hafling S.Martino in Badia Marling Villanders Villnöss La Valle Taufers im Münstertal Schluderns Schlanders Merano Avelengo Naturns Plaus Marlengo Villandro Funes Tubre Sluderno Silandro Naturno Plaus Tscherms Glurns Vöran Lajen Kastelbell-Tschars Cermes Glorenza Verano Barbian Laion Castelbello-Ciardes Lana Barbiano St.Ulrich Prad am Stilfser JochLaas Latsch Burgstall Waidbruck Abtei Lana Ortisei St.Christina in Gröden Prato allo Stelvio Lasa Laces St.Pankraz Postal Ponte Gardena Badia S.Pancrazio Gargazon Mölten S.Cristina Valgardena GargazzoneMeltina Jenesien Wolkenstein in Gröden Corvara Ritten Kastelruth Tisens S.Genesio Atesino Selva di Val Gardena Corvara in Badia Renon Castelrotto Tesimo Terlan Stilfs Nals Terlano Völs am Schlern Stelvio Nalles U.L.Frau i.W.-St.Felix Andrian Fie' allo Sciliar Martell Ulten Martello Senale-S.Felice Andriano Bozen Ultimo Proveis Bolzano Tiers Proves Tires Eppan a.d. -

Tabelle 1 – Pestizid-Untersuchungen Im Trinkwasser 2020

Tabelle 1 – Pestizid-Untersuchungen im Trinkwasser 2020 Im Jahr 2020 wurden in Südtirol 152 Wasserproben aus den untersuchten Probenentnahmepunkten innerhalb des öffentlichen Trinkwassernetzes auf Pestizide untersucht. In keiner der untersuchten Proben wurden Rückstände von Pestiziden nachgewiesen. 2020 Codice Codice Cod.Punto comune / acquedotto / Descrizione acquedotto / prelievo / Gemeinde- Comune / Kodex der Beschreibung der Kodex Descrizione punto di prelievo / kodex Gemeinde TWL Trinkwasserleitung Entnahmep. Beschreibung des Entnahmepunktes BRESSANONE/ Millan / Laboratorio riabilitativo "Kastell", Via Otto von Guggenberg 44 / 011 BRIXEN T0002 Milland E06 Reha- Werkstatt "Kastell", Otto von Guggenbergstr. 44; BRUNICO/ Brunico / Distretto / 013 BRUNECK T0001 Bruneck E15 Sprengel MONGUELFO - TESIDO/ Tesido / Hotel Alpenhof Tesitin / 052 WELSBERG - TAISTEN T0002 Taisten E03 Hotel Alpenhof Tesitin VALDAORA/ Valdaora / Casa di riposo / 106 OLANG T0001 Olang E12 Altersheim BRESSANONE/ Bressanone-Varna / Ospedale di Bressanone, Via Dante 53, radiologia / 011 BRIXEN T0001 Brixen-Vahrn E13 Krankenhaus Brixen, Dantestr. 53, Radiologie BOLZANO/ Bolzano / Scuola Materna O.N.M.I. / 008 BOZEN T0001 Bozen E07 Kindergarten O.N.M.I. FIÈ ALLO SCILIAR/ Fiè / Fontana pubblica Binderplatz / 031 VÖLS AM SCHLERN T0001 Völs E01 Öffentlicher Brunnen Binderplatz TIROLO/ Tirolo / f.p. sopra il municipio / 101 TIROL T0001 Dorf Tirol E01 Öffentlicher Brunnen oberhalb Gemeinde LANA/ Lana / f.p. p.zza della chiesa / 041 LANA T0001 Lana E01 Öffentlicher Brunnen Kirchplatz CHIENES/ Casteldarne / Ehrenburgerhof Lido / 021 KIENS T0002 Ehrenburg E03 Ehrenburgerhof Lido SAN LORENZO DI SEBATO/ S. Lorenzo / Municipio / 081 St. Lorenzen T0001 St. Lorenzen E07 Rathaus RENON/ Renon / scuola media Collalbo / 072 RITTEN T0001 Ritten E04 Mittelschule Klobenstein STELVIO/ Solda / Solda - stazione a valle - funivia / 095 STILFS T0004 Sulden E06 Sulden - Talstation Getscher Bahn STELVIO/ Stelvio / f.p. -

Note Adresse Indirizzo Bezeichnung Denominazione Anzahl Räume

Sanitätsbetrieb der Autonomen Provinz Bozen - Südtirol Azienda Sanitaria della Provinicia Autonoma di Bolzano - Alto Adige Immobilien Dritter in Nutzung Immobili detenuti di terzi Situation / Situazione 31/12/2020 Anzahl Räume / numero locali Zone Zona Gemeinde Comune Ortschaft Località Adresse Indirizzo Bezeichnung Denominazione Notizen Note Ambulatorium/ Warteraum/ Sala GESAMT/ Büro/ Ufficio WC/ Serivzi Sonstige/ Altro Ambulatorio attesa TOTALE Salten-Schlern-Ritten Salto-Sarentino-Renon Mölten Meltina Mölten Meltina Anton Oberrauch Strasse 1/A Via Anton Oberrauch 1/A Sprengelstützpunkt Punto di riferimento 3 1 2 2 8 Salten-Schlern-Ritten Salto-Sarentino-Renon Ritten Renon - Collalbo Ritten - Klobenstein Renon - Collalbo P. Mayr - Strasse 25 Via P. Mayr 25 Sprengelstützpunkt Punto di riferimento 5 1 3 5 14 Salten-Schlern-Ritten Salto-Sarentino-Renon Sarenthein Sarentino Sarenthein Srentino Postwiese 1 Via Postwiese 1 Sprengelstützpunkt Punto di riferimento 10 1 3 8 4 26 Salten-Schlern-Ritten Salto-Sarentino-Renon Jenesien San Genesio Jenesien San Genesio Atesino Schrann 10/a Via Schrann 10/a Sprengelstützpunkt Punto di riferimento 2 0 1 2 5 Überetsch Oltradige Terlan Terlano Terlan Terlano Niederthorstrasse 7 Via Niederthor 7 Sprengelstützpunkt Punto di riferimento 3 0 1 2 1 7 Überetsch Oltradige Kaltern Caldaro Kaltern Caldaro Rottenburgplatz 1 Piazza dei Rottenburg 1 Sprengelstützpunkt Punto di riferimento 6 0 3 3 3 15 Überetsch Oltradige Eppan a. d. Weinstrasse Appiano s. strada del vino Girlan Cornaiano Girlanerstrasse 3 Via Cornaiano 3 Ambulatorium Ambulatorio 1 0 1 2 4 nella scuola Überetsch Oltradige Eppan a. d. Weinstrasse Appiano s. strada del vino St. Pauls - Eppan San Paolo - Appiano St. Justina Weg 10 Via S. -

South Tyrol in Figures

South Tyrol in figures 2019 AUTONOME PROVINZ PROVINCIA AUTONOMA BOZEN - SÜDTIROL DI BOLZANO - ALTO ADIGE Landesinstitut für Statistik Istituto provinciale di statistica AUTONOMOUS PROVINCE OF SOUTH TYROL Provincial Statistics Institute General preliminary notes SIGNS Signs used in the tables of this publication: Hyphen (-): a) the attribute doesn’t exist b) the attribute exists and has been collected, but it doesn’t occur. Four dots (….): the attribute exists, but its frequency is unknown for various reasons. Two dots (..): Value which differs from zero but doesn’t reach 50% of the lowest unit that may be shown in the table. ABBREVIATIONS Abbreviations among the table sources: ASTAT: Provincial Statistics Institute ISTAT: National Statistics Institute ROUNDINGS Usually the values are rounded without considering the sum. Therefore may be minor differences between the summation of the single values and their sum in the table. This applies mainly to percentages and monetary values. PRELIMINARY AND RECTIFIED DATA Recent data is to be considered preliminary. They will be rectified in future editions. Values of older publications which differ from the data in the actual edition have been rectified. © Copyright: Autonomous Province of South Tyrol Provincial Statistics Institute - ASTAT Bozen / Bolzano 2019 Orders are available from: ASTAT Via Kanonikus-Michael-Gamper-Str. 1 I-39100 Bozen / Bolzano Tel. 0471 41 84 04 Fax 0471 41 84 19 For further information please contact: Statistische Informationsstelle / Centro d’informazione statistica Tel. 0471 41 84 04 The tables of this publication are https://astat.provinz.bz.it also to be found online at https://astat.provincia.bz.it E-mail: [email protected] [email protected] Reproduction and reprinting of tables and charts, even partial, is only allowed if the source is cited (title and publisher). -

From South Tyrol (Prov

Zootaxa 4435 (1): 001–089 ISSN 1175-5326 (print edition) http://www.mapress.com/j/zt/ Monograph ZOOTAXA Copyright © 2018 Magnolia Press ISSN 1175-5334 (online edition) https://doi.org/10.11646/zootaxa.4435.1.1 http://zoobank.org/urn:lsid:zoobank.org:pub:D750DA16-3755-4B69-AA4C-3B3DF2EF07BC ZOOTAXA 4435 Catalogue of oribatid mites (Acari: Oribatida) from South Tyrol (Prov. Bolzano, Italy) HEINRICH SCHATZ c/o Institute of Zoology, University of Innsbruck, Technikerstr. 25, 6020 Innsbruck, Austria. E-mail: [email protected] Magnolia Press Auckland, New Zealand Accepted by T. Pfingstl: 1 Mar. 2018; published: 19 Jun. 2018 Licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution License http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0 HEINRICH SCHATZ Catalogue of oribatid mites (Acari: Oribatida) from South Tyrol (Prov. Bolzano, Italy) (Zootaxa 4435) 89 pp.; 30 cm. 19 Jun. 2018 ISBN 978-1-77670-396-8 (paperback) ISBN 978-1-77670-397-5 (Online edition) FIRST PUBLISHED IN 2018 BY Magnolia Press P.O. Box 41-383 Auckland 1346 New Zealand e-mail: [email protected] http://www.mapress.com/j/zt © 2018 Magnolia Press ISSN 1175-5326 (Print edition) ISSN 1175-5334 (Online edition) 2 · Zootaxa 4435 (1) © 2018 Magnolia Press SCHATZ Table of contents Abstract . 4 Introduction . 4 Material and methods . 5 Species list . 8 Fam. Brachychthoniidae . 8 Fam. Eniochthoniidae . 11 Fam. Hypochthoniidae. 11 Fam. Mesoplophoridae . 12 Fam. Cosmochthoniidae . 12 Fam. Sphaerochthoniidae . 12 Fam. Heterochthoniidae. 12 Fam. Eulohmanniidae . 12 Fam. Epilohmanniidae. 13 Fam. Euphthiracaridae. 13 Fam. Oribotritiidae . 14 Fam. Phthiracaridae . 14 Fam. Crotoniidae . 17 Fam. Hermanniidae . 19 Fam. Malaconothridae . 19 Fam. -

Guida Vacanze Laives Bronzolo Vadena

Guida vacanze Escursioni in bici, camminate e tanto altro... 3 Un caloroso benvenuto nelle Mela & Piaceri Gastronomia località Laives, Bronzolo e Alto Adige, la terra delle mele ................................................................. 4 Gastronomia a Laives, Bronzolo e Vadena ................................... 36 - 37 Vadena! Laives, la città della mela ......................................................................... 5 Bar, Pasticcerie, Panifici ........................................................................... 38 La mela nelle quattro stagioni ................................................................. 6 Qui, nella parte bassa Indice Varietà della mela ....................................................................................... 7 dell’Alto Adige, potete godervi Mobilità l’affascinante combinazione Specialità alla mela ..................................................................................... 8 Mobilcard .................................................................................................... 39 di un’atmosfera mediterranea La Strada del Vino ....................................................................................... 9 e della cultura tradizionale. Specialità altoatesine e il tradizionale “Törggelen” ..................... 10 - 11 Tutto questo è incorporato in un mare di favolosi meleti. Le Numero d’emergenza 112 tre località sono il punto di Vacanze attive partenza ideale grazie alla loro Escursioni ............................................................................................. -

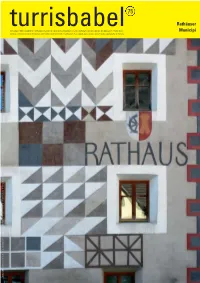

Rathäuser Municipi

75 turrisbabel Rathäuser Trimestrales Mitteilungsblatt der Stiftung der Kammer der Architekten, Raumplaner, Landschaftsplaner, Denkmalpfleger der Autonomen Provinz Bozen Municipi Notiziario trimestrale della Fondazione dell’Ordine degli Architetti, Pianificatori, Paesaggisti, Conservatori della Provincia Autonoma di Bolzano , rispedire all’ufficio di Bolzano C.P.O. per la restituzione al mittente che si impegna a corrispondere il diritto fisso , rispedire all’ufficio di Bolzano C.P.O. Spedizione in A.P. – D.L. 353/2003 (conv. in L. 27/02/2004 numero 47) art. 1, comma DCB Bolzano In caso di mancato recapito – D.L. 353/2003 (conv. Spedizione in A.P. Euro 8,00 Rathäuser / Municipi turrisbabel 75 2 116 comuni Carlo Calderan 8 Neubau Rathaus St. Lorenzen Kurt Egger und Armin Pedevilla 16 Municipio di Canazei, dialogo tra epoche e architetti weber + winterle 24 Il nuovo Centro del Comune di Laives Alessandro Scavazza 30 Municipio di Brunico Paola Attardo 34 Der (fast) neue Dorfkern in Völs Alexander Zoeggeler 38 Kreis für Jugend, Kunst und Kultur in St. Ulrich, Gröden Siegfried Delueg 46 Haus Valgrata. Gemeindezentrum Außervillgraten Hans-Peter Machné 50 Mehrzweckhaus der Gemeinde Hopfgarten in Osttirol Hans-Peter Machné 56 Rathaus Kastelbell-Tschars Walter Karl Dietl 64 Neues Rathaus in Nals Johann Vonmetz 70 Gemeindezentrum Plaus Emil Wörndle 76 Facciate poco comuni Cristina Vignocchi Wettbewerbe / Concorsi 80 Wettbewerb Rathaus Ulten Zusammengestellt von Elena Mezzanotte 88 Planungswettbewerb zur Errichtung eines Mehrzweckgebäudes und zur -

Da Ovest a Est 1. Prato Allo Stelv

SEELSORGEAMT UFFICIO PASTORALE OFIZE PASTORAL Nuova pianificazione delle unità pastorali – da ovest a est 1. Prato allo Stelvio-Agumes, Montechiaro, Stelvio, Trafoi, Solda 2. „Unità pastorale Curon Venosta” (Parrocchie Resia, S. Valentino alla Muta, Curon Venosta, Vallelunga), 3. Malles, Planol, Tarces, Mazia, Burgusio – OSB, Slingia – OSB, Laudes, Clusio, Sluderno, Glorenza, Tubre 4. Silandro, Corces, „Unità pastorale Lasa” (Parrocchie Lasa, Tanas, Oris, Cengles) 5. „Unità pastorale Laces-Martello” (Parrocchie Laces, Coldrano, Tarres, Martello, Morter) 6. „Unità pastorale Naturno” (Parrocchie Naturno, Tablà, Ciardes, Maragno/ Castelbello), Madonna di Senales, Certosa, Monte S. Caterina 7. „Unità pastorale Parcines” (Parrocchie Parcines, Rablà, Plaus) con Marlengo, Lagundo 8. Pastorale cittadina Merano: „Unità pastorale Merano” (Parrocchie Merano/St. Nikolaus, Maria Himmelfahrt, Maia Alta), Maia Bassa (ital.-ted.), Quarazze – OCist, S. Maria Assunta, S. Spirito, Sinigo (ital.-ted.) 9. S. Leonardo in Passiria – OT, Valtina, S. Martino in Passiria – OSB, Passo di Passiria, „Unità pastorale Alta Val Passiria” (Parrocchie Moso in Passiria, Stulles, Plata – OSB, Plan – OCist, Corvara in Passiria) 10. „Unità pastorale Scena” (Parrocchie Scena, Verdines, Talle, Avelengo), Tirolo, Rifiano, Caines 11. Lana – OT, Gargazzone – OT, Foiana – OT, Tesimo, Cermes, Postal, S. Felice, Senale – OSB, S. Pancrazio, S. Valburga, S. Nicolò, S. Geltrude, Lauregno, Proves Domplatz/ Piazza Duomo 2, I-39100 Bozen/Bolzano Tel. +39 0471 306 210, Fax +39 0471 980 959, [email protected], www.bz-bx.net 12. „Unità pastorale Val d’Adige” (Parrocchie Terlano, Settequerce – OT, Nalles, Andriano, Vilpiano), Meltina, Valas, Verano 13. Pastorale cittadina Bolzano: Avinga – OSB, B.V.M. del SS. Rosario, Corpus Domini, Cristo Re (ital.-ted.), Duomo (ital.-ted.), Madre Teresa di Calcutta, Gries – OSB (ital.-ted.), Piani di Bolzano, Regina Pacis (ital.-ted.), Rencio, Sacra Famiglia, S. -

Lista Veicoli

AUTONOME PROVINZ BOZEN PROVINCIA AUTONOMA DI BOLZANO Agentur Landesdomäne Agenzia Demanio provinciale Anlage/Allegato III ANFRAGE ANGEBOT FÜR FOLGENDE RICHIEDI OFFERTA PER I SEGUENTI SERVIZI : DIENSTLEISTUNGEN : GEGENSTAND DER AUSSCHREIBUNG OGGETTO DELL ’AFFIDAMENTO Die Vergabe besteht aus dem Dienst von Reparatur, Affidamento del servizio di riparazione, revisione, Überholung, routinemäßigen planmäßigen Wartungen des manutenzione ordinaria, programmata e delle parti Autos und der Lieferungen von mechanischen, elektrischen meccaniche, elettriche e degli pneumatici nonché la und pneumatischen Teilen. fornitura dei pezzi di ricambio e pneumatici. Los / Lotto Fahrzeuge / Veicoli Kennzeichen / Standort / Località Gemeinde / Targa Comune Manitou PR150 AHE746 Gärten Trauttmansdorff / Meran / Merano Giardini Trauttmansdorff Gärten Trauttmansdorff / Radlader Weidemann 1504 P43 AEW098 Meran / Merano Giardini Trauttmansdorff Gärten Trauttmansdorff / Vibrationsplatte Wacker Neuson VP1135 Meran / Merano Giardini Trauttmansdorff Gärten Trauttmansdorff / Zweitaktstampfer Wacker Neuson BS 60 2 11 Meran / Merano Giardini LOS/LOTTO I Trauttmansdorff Gärten BAUMASCHINE-MACCHINE EDILI Trauttmansdorff / Minibagger Neuson 28Z3 Meran / Merano Giardini Trauttmansdorff Gärten Trauttmansdorff / Dumper Neuson 2001 AFA637 Meran / Merano Giardini Trauttmansdorff Kramer Werke 341-02 AFW382 Aquatisches Artenschutzzentrum Schenna / Scena / Centro Tutela Specie Aquatiche Manitou MLT940-120HLSU AFW358 Sägewerk Latemar Welschnofen / / Segheria Latemar Nova Ponente Agrarbetrieb