The Value of Fungi

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Forgotten Kingdom Ecologically Industrious and Alluringly Diverse, Australia’S Puffballs, Earthstars, Jellies, Agarics and Their Mycelial Kin Merit Your Attention

THE OTHER 99% – NEGLECTED NATURE The delicate umbrellas of this Mycena species last only fleetingly, while its fungal mycelium persists, mostly obscured within the log it is rotting. Photo: Alison Pouliot A Forgotten Kingdom Ecologically industrious and alluringly diverse, Australia’s puffballs, earthstars, jellies, agarics and their mycelial kin merit your attention. Ecologist Alison Pouliot ponders our bonds with the mighty fungus kingdom. s the sun rises, I venture off-track Fungi have been dubbed the ‘forgotten into a dripping forest in the Otway kingdom’ – their ubiquity and diversity ARanges. Mountain ash tower contrast with the sparseness of knowledge overhead, their lower trunks carpeted about them, they are neglected in in mosses, lichens and liverworts. The conservation despite their ecological leeches are also up early and greet me significance, and their aesthetic and with enthusiasm. natural history fascination are largely A white scallop-shaped form at the unsung in popular culture. The term base of a manna gum catches my eye. ‘flora and fauna’ is usually unthinkingly Omphalotus nidiformis, the ghost fungus. A assumed to cover the spectrum of visible valuable marker. If it’s dark when I return, life. I am part of a growing movement of the eerie pale green glow of this luminous fungal enthusiasts dedicated to lifting fungal cairn will be a welcome beacon. the profile of the ‘third f’ in science, Descending deeper into the forest, a conservation and society. It is an damp funk hits my nostrils, signalling engrossing quest, not only because of the fungi. As my eyes adjust and the morning alluring organisms themselves but also for lightens, I make out diverse fungal forms the curiosities of their social and cultural in cryptic microcosms. -

Table of Contents

Table of Contents: Who is this for?... 3 Introduction... 3 Mechanic Overview... 4 Redesigned Herbalism Kit... 4 Herbalism Notebook... 5 5 Standard Recipes... 5 Deciphering & Copying a Recipe... 5 Replacing Your Notebook... 6 Foraging... 6 Crafting... 6 Learning New Recipes... 7 Obtaining a Recipe... 7 Deformulation of Existing Potions... 7 Discovery of Novel Potions... 8 Formulas... 9 33 Core Potions... 9 Example Homebrew Potions... 11 Appendix I: Biomes... 12 Appendix II: Damage Ingredients.... 15 Appendix III: Ingredient Descriptions... 16 Sample file 2 MEDICA PLANTARUM Enjoy the wonderful world of plants & fungi! Not for resale. For personal use only. Who is this for? Medica Plantarum was named after two ancient plant texts, Dioscorides’ De materia medica and Theophrastus’ Historia Plantarum, and is designed to expand on the role of herbalism in TTRPGs. It’s for players or GMs who think plants and fungi are cool, and are looking for an interesting way to bring some real botany into their games. On the surface, this is a mechanic to create new potions, fill party downtime, or inspire character agency. At its core, this is an educational guide for players or GMs who want to use real plant biology to inform their potion craft. Medica Plantarum presents biology, history, folklore, and mythology to give folks a unique lens in which to discover the wonder of plant diversity. The ultimate goal of this guide is to inspire players and GMs to create their own potions by learning about the plants around them. Introduction As a plant scientist and avid TTRPGer, I am always on the lookout for interesting ways to integrate plants into the campaigns I GM. -

Bioluminescence in Mushroom and Its Application Potentials

Nigerian Journal of Science and Environment, Vol. 14 (1) (2016) BIOLUMINESCENCE IN MUSHROOM AND ITS APPLICATION POTENTIALS Ilondu, E. M.* and Okiti, A. A. Department of Botany, Faculty of Science, Delta State University, Abraka, Nigeria. *Corresponding author. E-mail: [email protected]. Tel: 2348036758249. ABSTRACT Bioluminescence is a biological process through which light is produced and emitted by a living organism resulting from a chemical reaction within the body of the organism. The mechanism behind this phenomenon is an oxygen-dependent reaction involving substrates generally termed luciferin, which is catalyzed by one or more of an assortment of unrelated enzyme called luciferases. The history of bioluminescence in fungi can be traced far back to 382 B.C. when it was first noted by Aristotle in his early writings. It is the nature of bioluminescent mushrooms to emit a greenish light at certain stages in their life cycle and this light has a maximum wavelength range of 520-530 nm. Luminescence in mushroom has been hypothesized to attract invertebrates that aids in spore dispersal and testing for pollutants (ions of mercury) in water supply. The metabolites from luminescent mushrooms are effectively bioactive in anti-moulds, anti-bacteria, anti-virus, especially in inhibiting the growth of cancer cell and very useful in areas of biology, biotechnology and medicine as luminescent markers for developing new luminescent microanalysis methods. Luminescent mushroom is a novel area of research in the world which is beneficial to mankind especially with regards to environmental pollution monitoring and biomedical applications. Bioluminescence in fungi is a beautiful phenomenon to observe which should be of interest to Scientists of all endeavors. -

Pleurotus Species Basidiomycotina with Gills - Lignicolous Mushrooms

Biobritte Agro Solutions Private Limited, Kolhapur, (India) Jaysingpur-416101, Taluka-Shirol, District-Kolhapur, Maharashtra, INDIA. [email protected] www.biobritte.co.in Whatsapp: +91-9923806933 Phone: +91-9923806933, +91-9673510343 Biobritte English name Scientific Name Price Lead time Code Pleurotus species Basidiomycotina with gills - lignicolous mushrooms B-2000 Type A 3 Weeks Winter Oyster Mushroom Pleurotus ostreatus B-2001 Type A 3 Weeks Florida Oyster Mushroom Pleurotus ostreatus var. florida B-2002 Type A 3 Weeks Summer Oyster Mushroom Pleurotus pulmonarius B-2003 Type A 4 Weeks Indian Oyster Mushroom Pleurotus sajor-caju B-2004 Type B 4 Weeks Golden Oyster Mushroom Pleurotus citrinopileatus B-2005 Type B 3 Weeks King Oyster Mushroom Pleurotus eryngii B-2006 Type B 4 Weeks Asafetida, White Elf Pleurotus ferulae B-2007 Type B 3 Weeks Pink Oyster Mushroom Pleurotus salmoneostramineus B-2008 Type B 3 Weeks King Tuber Mushroom Pleurotus tuberregium B-2009 Type B 3 Weeks Abalone Oyster Mushroom Pleurotus cystidiosus Lentinula B-3000 Shiitake Lentinula edodes Type B 5 Weeks other lignicoles B-4000 Black Poplar Mushr. Agrocybe aegerita Type-C 5 Weeks B-4001 Changeable Agaric Kuehneromyces mutabilis Type-C 5 Weeks B-4002 Nameko Mushroom Pholiota nameko Type-C 5 Weeks B-4003 Velvet Foot Collybia Flammulina velutipes Type-C 5 Weeks B-4003-1 yellow variety 5 Weeks B-4003-2 white variety 5 Weeks B-4004 Elm Oyster Mushroom Hypsizygus ulmarius Type-C 5 Weeks B-4005 Buna-Shimeji Hypsizygus tessulatus Type-C 5 Weeks B-4005-1 beige variety -

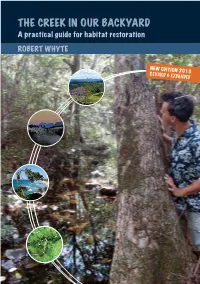

The Creek in Our Backyard a Practical Guide for Habitat Restoration

THE CREEK IN OUR BACKYARD A practical guide for habitat restoration ROBERT WHYTE NEW EDITION 2013 REVISED & EXPANDED PREFACE The creek in our backyard ike the air we breathe, our waterways are a A practical guide for habitat restoration shared resource, sustaining life. Creeks and by Robert Whyte rivers are a chain of fragile links connecting Lus to the nature with which we share our space. Thanks to funding from the Federal Government, For me, expanding this book for South East Save Our Waterways Now (SOWN) has been able to Queensland is like taking a deep breath – the literal produce this second, revised and expanded edition meaning of inspiration. Filling my lungs and hold- of The creek in our backyard. Special thanks to ing a moment of calm to cherish the opportunity we Deborah Metters, who helped with the ideas behind have in South East Queensland to live with nature. the reorganisation of the book and contributed Restoring our waterways is not just the ‘right’ stories and photos from the Land for Wildlife thing to do, it is essential. Yes we can do it. Yes we network, Glenn Leiper, Tim Low, Mark Crocker, must do it. With a little effort now, we can return Sharon Louise, Dick Harding, Nick Rains, Russell our creeks to health. Harisson, Tim Ransome and Anne Jones. Many Many of our older locals remember swimming other people helped with advice, proofreading, in crystal clear streams with diverse and abundant species identification and photos. Thank you all. wildlife, sharing the water with Platypus, turtles, eels and catfish. -

Pleurotus Ostreatus

Pleurotus Ostreatus Oyster Mushroom Pleurotus ostreatus, the oyster mushroom or oyster fungus, is a common edible mushroom. It was first cultivated in Germany as a subsistence measure during World War I and is now grown commercially around the world for food. It is related to the similarly cultivated king oyster mushroom. Oyster mushrooms can SCIENTIFIC CLASSIFICATION also be used industrially Kingdom : Fungi for mycoremediation purposes. Division : Basidiomycota Class : Agaricomycetes The oyster mushroom is one of the Order : Agaricales more commonly sought wild Family : Pleurotaceae mushrooms, though it can also be Genus : Pleurotus cultivated on straw and other media. It Species : P. ostreatus has the bittersweet aroma of benzaldehyde (which is also characteristic of bitter almonds). Binomial Name Pleurotus ostreatus Name Both the Latin and common names refer to the shape of the fruiting body. The Latin pleurotus (sideways) refers to the sideways growth of the stem with respect to the cap, while the Latin ostreatus (and the English common name, oyster) refers to the shape of the cap which resembles the bivalve of the same name. Many also believe that the name is fitting due to a flavor resemblance to oysters. The name oyster mushroom is also applied to other Pleurotus species. Or the grey oyster mushroom to differentiate it from other species in the genus. Description The mushroom has a broad, fan or oyster-shaped cap spanning 2– 3 3 30 cm ( ⁄4–11 ⁄4 in); natural specimens range from white to gray or tan to dark-brown; the margin is inrolled when young, and is smooth and often somewhat lobed or wavy. -

Antibacterial Agents from Lignicolous Macrofungi

18 Antibacterial Agents from Lignicolous Macrofungi Maja Karaman, Milan Matavulj and Ljiljana Janjic University of Novi Sad, Department of Biology and Ecology, Novi Sad Serbia 1. Introduction Since ancient times, the mushrooms have been prized as food as well as source for drugs, giving rise to an increasing interest today ("functional food"). Number of macrofungi is of a medicinal importance and represents an unlimited source of secondary metabolites of high medicinal value while a large number of biologically active molecules are identified in many species of macrofungi throughout the world (Wasser & Weis, 1999; Kitzberger et al., 2007; Barros et al., 2007; Turkoglu et al., 2007; Kim et al., 2008; 2007; Wasser, 2011). In addition, of importance is the amount of produced substances namely, they must be simple for the manufacturing (industrial synthesis) or there must be enough raw material for extraction of active molecules. Such molecules, if chemical groups responsible for biological activity are known, should serve as basic compounds for the synthesis of new molecules. Lignicolous macrofungi express significant biological effects, including antibacterial activity (Hur et al., 2004; Ishikawa et al., 2005; Kalyoncu et al., 2010) and their secondary metabolites can be easily extracted and identified. It has been found that secondary metabolites are very divergent in structure and play no essential role in their growth and reproduction, but probably have a function in biochemical evolution of a species ensuring its survival (Engler et al., 1998). The presence of these compounds in macrofungi is genetically determined, but also varies as a function of ecological factors and the growth stage of these organisms (Puttaraju et al., 2006). -

UWA Microbush Fungi Report 2005

UWA Microbush Fungi Report 2005 Nineteen people attended the PUBF Fungi Practical Class for Environmental Microbiology at the University of Western Australia Microbiology Department and the “Microbush” next door on 20 July 2005, held between 2-5pm. The walk was organised together with the Microbiology Department of the University of Western Australia. Two groups collected fungi, led by Roz Hart of the PUBF Project and David Sutton, Lecturer from the University of Western Australia. Ghost fungus Omphalotus nidiformis Unknown vouchered resupinate Tubaria sp . Common Rosegill Volvariella speciosa Recommendation : This list represents a very small portion of the fungi which are likely to be present in this reserve. Due to the nature of fungi, which fruit irregularly and intermittently, it will be necessary to conduct many such surveys over different days in the fungi season as well as in successive years to produce an accurate inventory of the fungi present in this valuable urban bush reserve. Perth Urban Bushland Fungi Project, UWA Fungi Report 2005 StreetExpress Map showing the location of the UWA Microbush site in Nedlands Aerial photo showing the track walked by Roz Hart’s group. StreetExpress map reproduced with permission of DLI, P332, Aerial photos reproduced with permission of DLI, 13/2005. Page 2 OziExplorer and OziPhotoTool were used to produce the track and linked fungi photos. Perth Urban Bushland Fungi Project, UWA Fungi Report 2005 UWA Microbush Fungi List 2005 Fungi names are provisional only as many of these fungi have not been examined in detail to confirm the names. The list below contains all the fungi recorded by the 4 groups. -

Omphalotus Nidiformis – the Ghost Fungus

Fungus of the Month – February 2012 © Richard Robinson Omphalotus nidiformis – the ghost fungus The ghost fungus, Omphalotus nidiformis, is common throughout southern and subtropical eastern Australia. It fruits, generally in large clusters, at the base of both living and dead trees. In Western Australia, it is common on living or dead bull banksia (Banksia grandis), peppermint (Agonis flexuosa), sheoak (Allocasuarina spp.) and marri (Corymbia calophylla) as well as understory shrubs and plants in jarrah forest and coastal woodlands. The funnel- or fan- shaped caps are generally 8-15 cm across and creamy white in colour with brownish or purple staining, especially near the depressed central region. The gills are creamy white, crowded and extend a short distance down the stem. The stem is often obscured by the dense cluster of caps but is attached strongly to the surface of the tree on which the ghost fungus is growing. The ghost fungus gets its name from its habit of being luminescent. In the dark the ghost fungus glows an eerie green colour (see inset). The intensity of the luminescence varies and diminishes with age or if the caps get too wet. The reason for its luminescent is not known, but perhaps it is to attract night flying insects which possibly feed on it and spread its spores. The scientific name refers to the form and habit of the fruit bodies. Omphal-: naval (umbilicus), -otus: resembling or similar, nid-: nest, -formis: resembling in shape or form. Richard Robinson, DEC Science Division, Manjimup . -

Omphalotus Nidiformis — Ghost Fungus

Fungus Factsheet 59 / 2012 Science Division Omphalotus nidiformis — ghost fungus Richard Robinson, Science Division, Manjimup, [email protected] © Richard Robinson Omphalotus nidiformis, or the ghost fungus, is common throughout southern and subtropical eastern Australia. It generally fruits in autumn, in large clusters at the base of both living and dead trees. In Western Australia, it’s common on living or dead bull banksia (Banksia grandis), peppermint (Agonis flexuosa), sheoak (Allocasuarina spp.) and marri (Corymbia calophylla) as well as understory shrubs and plants in jarrah forest and coastal woodlands. Caps are funnel- or fan-shaped, generally 8–15cm across, creamy white in colour with brownish or purple staining, especially near the depressed central region. Gills are creamy white, crowded and extend a short distance down the stem. Stems are often obscured by the dense cluster of caps but are attached strongly to the surface of the tree on which the ghost fungus is growing. The ghost fungus gets its name from its habit of being luminescent. In the dark the ghost fungus glows an eerie green colour (inset above). The intensity of the luminescence varies and diminishes with age or if the caps get too wet. The reason for its luminescent is not known, but perhaps it is to attract night flying insects which feed or forage on it and then spread its spores. The scientific name refers to the form and habit of the fruit bodies. Omphal-: naval (umbilicus), -otus: resembling or similar, nid-: nest, -formis: resembling in shape or form. Produced and published by the Science Division, Department of Environment and Conservation, Western Australia, Locked Bag 104, Bentley Delivery Centre, WA 6983 . -

FUNGI of AUSTRALIA Volume 1A Introduction—Classification

FUNGI OF AUSTRALIA Volume 1A Introduction—Classification History of the taxonomic study of Australian fungi Tom W.May & Ian G.Pascoe This volume was published before the Commonwealth Government moved to Creative Commons Licensing. © Commonwealth of Australia 1996. This work is copyright. You may download, display, print and reproduce this material in unaltered form only (retaining this notice) for your personal, non-commercial use or use within your organisation. Apart from any use as permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, no part may be reproduced or distributed by any process or stored in any retrieval system or data base without prior written permission from the copyright holder. Requests and inquiries concerning reproduction and rights should be addressed to: [email protected] FLORA OF AUSTRALIA The Fungi of Australia is a major new series, planned to comprise 60 volumes (many of multiple parts), which will describe all the indigenous and naturalised fungi in Australia. The taxa of fungi treated in the series includes members of three kingdoms: the Protoctista (the slime moulds), the Chromista (the chytrids and hyphochytrids) and the Eumycota. The series is intended for university students and interested amateurs, as well as professional mycologists. Volume 1A is one of two introductory volumes to the series. The major component of the volume is a discussion on the classification of the fungi, including a new classification, and keys to orders of worldwide scope. The volume also contains a chapter on the biology of the fungi, chapters on the Australian aspects of the history of mycology, biogeography and the fossil record, and an extensive glossary to mycological terms. -

Mycena Genomes Resolve the Evolution of Fungal Bioluminescence

Mycena genomes resolve the evolution of fungal bioluminescence Huei-Mien Kea,1, Hsin-Han Leea, Chan-Yi Ivy Lina,b, Yu-Ching Liua, Min R. Lua,c, Jo-Wei Allison Hsiehc,d, Chiung-Chih Changa,e, Pei-Hsuan Wuf, Meiyeh Jade Lua, Jeng-Yi Lia, Gaus Shangg, Rita Jui-Hsien Lud,h, László G. Nagyi,j, Pao-Yang Chenc,d, Hsiao-Wei Kaoe, and Isheng Jason Tsaia,c,1 aBiodiversity Research Center, Academia Sinica, Taipei 115, Taiwan; bDepartment of Molecular, Cellular and Developmental Biology, Yale University, New Haven, CT 06520; cGenome and Systems Biology Degree Program, Academia Sinica and National Taiwan University, Taipei 106, Taiwan; dInstitute of Plant and Microbial Biology, Academia Sinica, Taipei 115, Taiwan; eDepartment of Life Sciences, National Chung Hsing University, Taichung 402, Taiwan; fMaster Program for Plant Medicine and Good Agricultural Practice, National Chung Hsing University, Taichung 402, Taiwan; gDepartment of Biotechnology, Ming Chuan University, Taoyuan 333, Taiwan; hDepartment of Medicine, Washington University in St. Louis, St. Louis, MO 63110; iSynthetic and Systems Biology Unit, Biological Research Centre, 6726 Szeged, Hungary; and jDepartment of Plant Anatomy, Institute of Biology, Eötvös Loránd University, Budapest, 1117 Hungary Edited by Manyuan Long, University of Chicago, Chicago, IL, and accepted by Editorial Board Member W. F. Doolittle October 28, 2020 (received for review May 27, 2020) Mushroom-forming fungi in the order Agaricales represent an in- fungi of three lineages: Armillaria, mycenoid, and Omphalotus dependent origin of bioluminescence in the tree of life; yet the (7). Phylogeny reconstruction suggested that luciferase origi- diversity, evolutionary history, and timing of the origin of fungal nated in early Agaricales.