Swiss Perceptions of Informal Imperialism in China in the 1920S

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Guangzhou-Hongkong Strike, 1925-1926

The Guangzhou-Hongkong Strike, 1925-1926 Hongkong Workers in an Anti-Imperialist Movement Robert JamesHorrocks Submitted in accordancewith the requirementsfor the degreeof PhD The University of Leeds Departmentof East Asian Studies October 1994 The candidateconfirms that the work submitted is his own and that appropriate credit has been given where referencehas been made to the work of others. 11 Abstract In this thesis, I study the Guangzhou-Hongkong strike of 1925-1926. My analysis differs from past studies' suggestions that the strike was a libertarian eruption of mass protest against British imperialism and the Hongkong Government, which, according to these studies, exploited and oppressed Chinese in Guangdong and Hongkong. I argue that a political party, the CCP, led, organised, and nurtured the strike. It centralised political power in its hands and tried to impose its revolutionary visions on those under its control. First, I describe how foreign trade enriched many people outside the state. I go on to describe how Chinese-run institutions governed Hongkong's increasingly settled non-elite Chinese population. I reject ideas that Hongkong's mixed-class unions exploited workers and suggest that revolutionaries failed to transform Hongkong society either before or during the strike. My thesis shows that the strike bureaucracy was an authoritarian power structure; the strike's unprecedented political demands reflected the CCP's revolutionary political platform, which was sometimes incompatible with the interests of Hongkong's unions. I suggestthat the revolutionary elite's goals were not identical to those of the unions it claimed to represent: Hongkong unions preserved their autonomy in the face of revolutionaries' attempts to control Hongkong workers. -

How to Review for 185B

How To Review for 185B • Go through your lecture notes – I will put overviews of lectures at my history department’s website – Study guide will be sent out at the end of this week • Go through your textbook • Go through your readings • Extended Office Hour Next Wednesday Lecture 1 Geography of China • Diverse, continent-sided empire • North vs. South • China’s Rivers RIVERS Yellow 黃河 Yangzi 長江 West 西江/珠江 Beijing 北京 Shanghai 上海 Hong Kong (Xianggang) 香港 Lecture 2 Legacies of the Qing Dynasty 1. The Qing Empire (Multi-ethnic Empire) 2. The 1911 Revolution 3. Imperialisms in China 4. Wordlordism and the Early Republic Qing Dynasty Sun Yat-sen 孙中山 Queue- cutting: 1911 The Abdication of Qing • Yuan Shikai – Negotiation between Yuan (on behalf of the Republican) and the Qing State • Abdication of Qing: Feb 12, 1912 • Yuan became the second provisional president Feb 14, 1912 China’s Last Emperor Xuantong 宣统 (Puyi 溥仪) Threats to China Lecture 3 Early Republic 1. The Yuan Shikai Era: a revisionist history 2. Yuan Shikai’s Rule 3. The Beijing Government 4. Warlords in China Yuan Shikai’s Era The New Republic • The New Election – Guomindang – Progressive Party • The Yuan Shikai Era – Challenges –Problems Beijing Government • Chaotic • Constitutional Warlordism • Militarists? • Cliques under Constitutional Government • The Warlord Era Lecture 4 The New Cultural Movement and the May Fourth 1. China and Chinese Culture in Traditional Time 2. The 1911 Revolution and the Change of Political Culture 3. The New Cultural Movement 4. The May Fourth Movement -

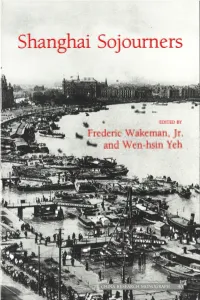

Shanghai Sojourners

CHINA RESEARCH MONOGRAPH 40 FM, INSTITUTE OF EAST ASIAN STUDIES ~~ UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA • BERKELEY C(S CENTER FOR CHINESE STUDIES Shanghai Sojourners EDITED BY Frederic Wakeman, Jr., and Wen-hsin Yeh A publication of the Institute of East Asian Studies, University of California at Berkeley. Although the Institute of East Asian Studies is responsible for the selec tion and acceptance of manuscripts in this series, responsibility for the opinions expressed and for the accuracy of statements rests with their authors. Correspondence may be sent to: Ms. Joanne Sandstrom, Managing Editor Institute of East Asian Studies University of California Berkeley, California 94 720 The China Research Monograph series, whose first title appeared in 1967, is one of several publications series sponsored by the Institute of East Asian Studies in conjunction with its constituent units. The others include the Japan Research Monograph series, the Korea Research Monograph series, the Indochina Research Monograph series, and the Research Papers and Policy Studies series. A list of recent publications appears at the back of the book. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Shanghai sojourners I Frederic E. Wakeman, Jr. , Wen-hsin Yeh, editors. p. em. - (China research monograph ; no. 40) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 1-55729-035-0 (paper) : $20.00 l. Shanghai (China)-History. I. Wakeman, Frederic E. II . Yeh, Wen Hsin. III. Series. DS796.5257S57 1992 95l.l'32-dc20 92-70468 CIP Copyright © 1992 by The Regents of the University of California ISBN 1-55729-035-0 Library of Congress Catalog Card Number 92-70468 Printed in the United States of America All rights reserved. -

Networks, Parties, and the “Oppressed Nations”: the Comintern and Chinese Communists Overseas, 1926–1935

Networks, Parties, and the “Oppressed Nations”: The Comintern and Chinese Communists Overseas, 1926–1935 Anna Belogurova, Freie Universität Berlin Abstract In the late 1920s, the overseas chapters of the Chinese Communist Party allied with the Third Communist International (Comintern)’s pursuit of world revolution and made efforts to take part in anti-colonial movements around the world. As Chinese migrant revolutionaries dealt with discrimination in their adopted countries, they promoted local, Chinese, and world revolutions, borrowing ideas from various actors while they built their organizations and contributed to the project of China’s revival. This article offers a window into the formation of globally connected Chinese revolutionary networks and explores their engagement with Comintern internationalism in its key enclaves in Berlin, San Francisco, Havana, Singapore, and Manila. These engagements built on existing ideas about China’s revival and channeled localization needs of the Chinese migrant Communists. The article draws on sources deposited in the Comintern archive in Moscow (RGASPI), as well as on personal reminiscences published as literary and historical materials (wenshi ziliao). Keywords: Chinese Communist Party overseas, Guomindang, Comintern, League against Imperialism, anti-colonialism, San Francisco Chinese, Berlin Chinese, Manila Chinese, Chinese in Singapore, Chinese in Philippines, internationalism, interwar period, institutional borrowing This article offers a snapshot of how Chinese Communist networks took shape -

The Foundations of Mao Zedong's Political Thought 1917–1935

The Foundations of Mao Zedong’s Political Thought The Foundations of Mao Zedong’s Political Thought 1917–1935 BRANTLY WOMACK The University Press of Hawaii ● Honolulu Open Access edition funded by the National Endowment for the Humanities / Andrew W. Mellon Foundation Humanities Open Book Program. Licensed under the terms of Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 In- ternational (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits readers to freely download and share the work in print or electronic format for non-commercial purposes, so long as credit is given to the author. Derivative works and commercial uses require per- mission from the publisher. For details, see https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/. The Cre- ative Commons license described above does not apply to any material that is separately copyrighted. Open Access ISBNs: 9780824879204 (PDF) 9780824879211 (EPUB) This version created: 17 May, 2019 Please visit www.hawaiiopen.org for more Open Access works from University of Hawai‘i Press. COPYRIGHT © 1982 BY THE UNIVERSITY PRESS OF HAWAII ALL RIGHTS RESERVED For Tang and Yi-chuang, and Ann, David, and Sarah Contents Dedication iv Acknowledgments vi Introduction vii 1 Mao before Marxism 1 2 Mao, the Party, and the National Revolution: 1923–1927 32 3 Rural Revolution: 1927–1931 83 4 Governing the Chinese Soviet Republic: 1931–1934 143 5 The Foundations of Mao Zedong’s Political Thought 186 Notes 203 v Acknowledgments The most pleasant task of a scholar is acknowledging the various sine quae non of one’s research. Two in particular stand out. First, the guidance of Tang Tsou, who has been my mentor since I began to study China at the University of Chicago. -

The Shanghai International Settlement and Newspaper Nationalism, 1925 Ziyu

Reading the May 30 Movement in Newspapers: The Shanghai International Settlement and Newspaper Nationalism, 1925 Ziyu (Steve) Gan HIST 400B: Senior Thesis Advised by Professors Paul Smith and Linda Gerstein May 1, 2020 Table of Contents Abstract ......................................................................................................................................................... 2 Acknowledgment .......................................................................................................................................... 4 Introduction ................................................................................................................................................... 5 A Note on Terminologies .......................................................................................................................... 6 The Shanghai International Settlement ..................................................................................................... 7 Secondary Literature Review .................................................................................................................... 7 Introducing Sources .................................................................................................................................. 9 The Question of the Public Sphere ......................................................................................................... 11 Multiple Voices of the Nation ................................................................................................................ -

Script Crisis and Literary Modernity in China, 1916-1958 Zhong Yurou

Script Crisis and Literary Modernity in China, 1916-1958 Zhong Yurou Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2014 © 2014 Yurou Zhong All rights reserved ABSTRACT Script Crisis and Literary Modernity in China, 1916-1958 Yurou Zhong This dissertation examines the modern Chinese script crisis in twentieth-century China. It situates the Chinese script crisis within the modern phenomenon of phonocentrism – the systematic privileging of speech over writing. It depicts the Chinese experience as an integral part of a worldwide crisis of non-alphabetic scripts in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. It places the crisis of Chinese characters at the center of the making of modern Chinese language, literature, and culture. It investigates how the script crisis and the ensuing script revolution intersect with significant historical processes such as the Chinese engagement in the two World Wars, national and international education movements, the Communist revolution, and national salvation. Since the late nineteenth century, the Chinese writing system began to be targeted as the roadblock to literacy, science and democracy. Chinese and foreign scholars took the abolition of Chinese script to be the condition of modernity. A script revolution was launched as the Chinese response to the script crisis. This dissertation traces the beginning of the crisis to 1916, when Chao Yuen Ren published his English article “The Problem of the Chinese Language,” sweeping away all theoretical oppositions to alphabetizing the Chinese script. This was followed by two major movements dedicated to the task of eradicating Chinese characters: First, the Chinese Romanization Movement spearheaded by a group of Chinese and international scholars which was quickly endorsed by the Guomingdang (GMD) Nationalist government in the 1920s; Second, the dissident Chinese Latinization Movement initiated in the Soviet Union and championed by the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) in the 1930s. -

From Imperial Soldier to Communist General: the Early Career of Zhu De and His Influence on the Formation of the Chinese Red Army

FROM IMPERIAL SOLDIER TO COMMUNIST GENERAL: THE EARLY CAREER OF ZHU DE AND HIS INFLUENCE ON THE FORMATION OF THE CHINESE RED ARMY By Matthew William Russell B.A. June 1983, Northwestern University M.A. June 1991, University of California, Davis M.Phil. May 2006, The George Washington University A Dissertation submitted to The Faculty of Columbian College of Arts and Sciences of The George Washington University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy May 17, 2009 Dissertation directed by Edward A. McCord Associate Professor of History and International Affairs The Columbian College of Arts and Sciences of The George Washington University certifies that Matthew W. Russell has passed the Final Examination for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy as of March 25, 2009. This is the final and approved form of the dissertation. FROM IMPERIAL SOLDIER TO COMMUNIST GENERAL: THE EARLY CAREER OF ZHU DE AND HIS INFLUENCE ON THE FORMATION OF THE CHINESE RED ARMY Matthew William Russell Dissertation Research Committee: Edward A. McCord, Associate Professor of History and International Affairs, Dissertation Director Ronald H. Spector, Professor of History and International Affairs, Committee Member Daqing Yang, Associate Professor of History and International Affairs, Committee Member ii © Copyright 2009 by Matthew W. Russell All rights reserved iii Dedication This work is dedicated to my mother Dorothy Diana Ing Russell and to my wife Julia Lynn Painton. iv Acknowledgements I was extremely fortunate to have Edward McCord as my adviser, teacher, and dissertation director, and I would not have been able to complete this program without his sound advice, guidance, and support. -

Government Gangsters

Government Gangsters: The Green Gang and the Guomindang 1927-1937 Presented to The Faculty of the Departments of History and Political Science The Colorado College In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Bachelor of Arts By Julian Henri Neylan May 2017 2 Introduction From 1932-1939, the Guomindang regime in China under Chiang Kai-Shek (1887-1975) collaborated with the Shanghai Green Gang; a secret society that engaged in criminal activities. The Guomindang, also referred to as the Nationalist party, was a political party founded in 1911 that ruled over China from 1927 until 1949. In 1932, The Guomindang was in dire need of revenue and needed to extract any financial resources they could from every level of Shanghai society. The power of the local Guomindang party branch in Shanghai was not sufficient to enforce the law, so illicit elements such as the Green Gang were able to make a profit on the margins of society. Instead of fighting entrenched criminal enterprises, the Guomindang used the Green Gang to gain revenue and further government interests within the city. The union of the Government and the Gang benefited both, as the Guomindang needed revenue from narcotics sales and the Green Gang needed government backed security and legitimacy to run their massive drug distribution networks and enter the financial world of Shanghai. Despite the Guomindang and the Green Gang’s mutual benefit, there were areas in which the collaboration did not work. The conditions that allowed the Guomindang to back Green Gang opium distribution were easily disrupted, especially when negative media attention emerged. -

The London School of Economics and Political Science British Opinion

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by LSE Theses Online 1 The London School of Economics and Political Science British Opinion and Policy towards China, 1922-1927 Phoebe Chow A thesis submitted to the Department of International History of the London School of Economics for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, London, November 2011 2 Declaration I certify that the thesis I have presented for examination for the PhD degree of the London School of Economics and Political Science is solely my own work other than where I have clearly indicated that it is the work of others (in which case the extent of any work carried out jointly by me and any other person is clearly identified in it). The copyright of this thesis rests with the author. Quotation from it is permitted, provided that full acknowledgement is made. This thesis may not be reproduced without the prior written consent of the author. I warrant that this authorisation does not, to the best of my belief, infringe the rights of any third party. Phoebe Chow 3 Abstract Public opinion in Britain influenced the government’s policy of retreat in response to Chinese nationalism in the 1920s. The foreigners’ rights to live, preach, work and trade in China extracted by the ‘unequal treaties’ in the nineteenth century were challenged by an increasingly powerful nationalist movement, led by the Kuomintang, which was bolstered by Soviet support. The Chinese began a major attack on British interests in June 1925 in South China and continued the attack as the Kuomintang marched upward to the Yangtze River, where much of British trade was centred. -

Key to Modern China

Syllabus of Record Program: CET Shanghai Course Code / Title: (SH/HIST 350) Shanghai: Key to Modern China? Total Hours: 45 Recommended Credits: 3 Primary Discipline / Suggested Cross Listings: History / East Asian Studies, International Relations, Urban Studies Language of Instruction: English Prerequisites/Requirements: None Description The city of Shanghai has had multiple and changing historical representations. It has been simultaneously blamed as the source of all that was wrong in China and praised as the beacon of an advanced national future. Historically, the city has been the empire’s cotton capital, a leading colonial-era treaty port, the location of Chinese urban modernity, a national center of things from finance to publishing, an exotic space that attracted and repelled, a home to new ideas and public activism, and the country’s industrial powerhouse. This course examines the social, political, economic, and cultural history of Shanghai and uses it to analyze if and how the city’s history provides keys to understanding the making of modern China. After a critical examination of concepts of tradition and modernity and approaches that have been used to understand Shanghai history, the class explores the city during the late imperial, Republican, and People’s Republic periods. Throughout, it contends with the contemporary return of Shanghai to urban preeminence and how this process intersects with the city’s history. Themes include commercialism, modernity, how the city's “semi-colonial” past has shaped its history, migration, and whether Shanghai is somehow unique or representative of what we know as modern China. The course takes advantage of its location with at least three field classes at significant historical sites and exhibits. -

Chinatown Was Made up of One Stretch Along Empire Street

THE CENTRAL KINGDOM, CONTINUED GO BACK TO THE PREVIOUS PERIOD 1900 It was after foreign soldiers had gunned down hundreds of Chinese (not before, as was reported), that a surge of Boxers laid siege to the foreign legations in Peking (Beijing). A letter from British Methodist missionary Frederick Brown was printed in the New-York Christian Advocate, reporting that his district around Tientsin was being overrun by Boxers. The German Minister to Beijing and at least 231 other foreign civilians, mostly missionaries, lost their lives. An 8-nation expeditionary force lifted the siege. “NARRATIVE HISTORY” AMOUNTS TO FABULATION, THE REAL STUFF BEING MERE CHRONOLOGY When the Chinese military bombarded the Russians across the Amur River, the Russian military responded by herding thousands of members of the local Chinese population to their deaths in that river. Surprise, the Russians didn’t really want the Chinese around. At about the turn of the century the area of downtown Providence, Rhode Island available to its Chinese population was being narrowed down, by urban renewal projects, to the point that all of Chinatown was made up of one stretch along Empire Street. Surprise, the white people didn’t really want the Chinese around. In this year or the following one, the Quaker schoolhouse near Princeton, New Jersey, virtually abandoned and a ruin, would be torn down. The land on which it stood is now the parking lot of the new school. An American company, Quaker Oats, had obtained hoardings in the vicinity of the white cliffs of Dover, England, for purposes of advertising use.