Government Gangsters

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Guangzhou-Hongkong Strike, 1925-1926

The Guangzhou-Hongkong Strike, 1925-1926 Hongkong Workers in an Anti-Imperialist Movement Robert JamesHorrocks Submitted in accordancewith the requirementsfor the degreeof PhD The University of Leeds Departmentof East Asian Studies October 1994 The candidateconfirms that the work submitted is his own and that appropriate credit has been given where referencehas been made to the work of others. 11 Abstract In this thesis, I study the Guangzhou-Hongkong strike of 1925-1926. My analysis differs from past studies' suggestions that the strike was a libertarian eruption of mass protest against British imperialism and the Hongkong Government, which, according to these studies, exploited and oppressed Chinese in Guangdong and Hongkong. I argue that a political party, the CCP, led, organised, and nurtured the strike. It centralised political power in its hands and tried to impose its revolutionary visions on those under its control. First, I describe how foreign trade enriched many people outside the state. I go on to describe how Chinese-run institutions governed Hongkong's increasingly settled non-elite Chinese population. I reject ideas that Hongkong's mixed-class unions exploited workers and suggest that revolutionaries failed to transform Hongkong society either before or during the strike. My thesis shows that the strike bureaucracy was an authoritarian power structure; the strike's unprecedented political demands reflected the CCP's revolutionary political platform, which was sometimes incompatible with the interests of Hongkong's unions. I suggestthat the revolutionary elite's goals were not identical to those of the unions it claimed to represent: Hongkong unions preserved their autonomy in the face of revolutionaries' attempts to control Hongkong workers. -

Shanghai, China's Capital of Modernity

SHANGHAI, CHINA’S CAPITAL OF MODERNITY: THE PRODUCTION OF SPACE AND URBAN EXPERIENCE OF WORLD EXPO 2010 by GARY PUI FUNG WONG A thesis submitted to The University of Birmingham for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOHPY School of Government and Society Department of Political Science and International Studies The University of Birmingham February 2014 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. ABSTRACT This thesis examines Shanghai’s urbanisation by applying Henri Lefebvre’s theories of the production of space and everyday life. A review of Lefebvre’s theories indicates that each mode of production produces its own space. Capitalism is perpetuated by producing new space and commodifying everyday life. Applying Lefebvre’s regressive-progressive method as a methodological framework, this thesis periodises Shanghai’s history to the ‘semi-feudal, semi-colonial era’, ‘socialist reform era’ and ‘post-socialist reform era’. The Shanghai World Exposition 2010 was chosen as a case study to exemplify how urbanisation shaped urban experience. Empirical data was collected through semi-structured interviews. This thesis argues that Shanghai developed a ‘state-led/-participation mode of production’. -

Swiss Perceptions of Informal Imperialism in China in the 1920S

Zurich Open Repository and Archive University of Zurich Main Library Strickhofstrasse 39 CH-8057 Zurich www.zora.uzh.ch Year: 2014 A tricky business: Swiss perceptions of informal imperialism in China in the 1920s Knüsel, Ariane Abstract: This article analyzes the role that commercial interests played in Swiss perceptions of infor- mal imperialism in China during the 1920s. Commercial interests were the driving force behind the establishment of Swiss relations with China in 1918 and Swiss rejections of Chinese demands to abolish extraterritoriality in the 1920s. Swiss commercial relations with China were deeply rooted in the social, economic, and political institutions and processes developed by informal imperialism in China. During the Chinese antiforeign agitation in the 1920s, the Swiss press criticized the unequal treaties as an example of imperialism in China but ignored Switzerland’s participation in it. This discrepancy between the official and media perceptions of Swiss commercial interests in China was caused by the fact that Switzerland’s dependence on privileges connected to the unequal treaties clashed with Swiss national mythology, which was based on neutrality and anti-imperial narratives. Moreover, the negligible importance attributed to Swiss trade with China and the increasing focus on the nationality of foreign companies in China allowed the Swiss media to ignore Swiss commercial interests in China. As a result, Swiss complicity in informal imperialism was downplayed by the Swiss press, which ignored the importance of Swiss commerce to Sino–Swiss relations. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/17535654.2014.960152 Posted at the Zurich Open Repository and Archive, University of Zurich ZORA URL: https://doi.org/10.5167/uzh-109310 Journal Article Accepted Version Originally published at: Knüsel, Ariane (2014). -

Virtual Shanghai

ASIA mmm i—^Zilll illi^—3 jsJ Lane ( Tail Sttjaca, New Uork SOif /iGf/vrs FO, LIN CHARLES WILLIAM WASON COLLECTION Draper CHINA AND THE CHINESE L; THE GIFT OF CHARLES WILLIAM WASON CLASS OF 1876 House 1918 WINE ATJD~SPIRIT MERCHANTS. PROVISION DEALERS. SHIP CHANDLERS. yigents for jfidn\iratty C/jarts- HOUSE BOATS supplied with every re- quisite for Up-Country Trips. LANE CRAWFORD 8 CO., LTD., NANKING ROAD, SHANGHAI. *>*N - HOME USE RULES e All Books subject to recall All borrowers must regis- ter in the library to borrow books fdr home use. All books must be re- turned at end of college year for inspection and repairs. Limited books must be returned within the four week limit and not renewed. Students must return all books before leaving town. Officers should arrange for ? the return of books wanted during their absence from town. Volumes of periodicals and of pamphlets are held in the library as much as possible. For special pur- poses they are given out for a limited time. Borrowers should not use their library privileges for the benefit of other persons Books of special value nd gift books," when the giver wishes it, are not allowed to circulate. Readers are asked to re- port all cases of books marked or mutilated. Do not deface books by marks and writing. - a 5^^KeservaToiioT^^ooni&^by mail or cable. <3. f?EYMANN, Manager, The Leading Hotel of North China. ^—-m——aaaa»f»ra^MS«»» C UniVerS"y Ubrary DS 796.S5°2D22 Sha ^mmmmilS«u,?,?llJff travellers and — — — — ; KELLY & WALSH, Ltd. -

The Generalissimo

the generalissimo ګ The Generalissimo Chiang Kai- shek and the Struggle for Modern China Jay Taylor the belknap press of harvard university press Cambridge, Massachusetts London, En gland 2009 .is Chiang Kai- shek’s surname ګ The character Copyright © 2009 by the President and Fellows of Harvard College All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America Library of Congress Cataloging- in- Publication Data Taylor, Jay, 1931– The generalissimo : Chiang Kai- shek and the struggle for modern China / Jay Taylor.—1st. ed. â p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978- 0- 674- 03338- 2 (cloth : alk. paper) 1. Chiang, Kai- shek, 1887–1975. 2. Presidents—China— Biography. 3. Presidents—Taiwan—Biography. 4. China—History—Republic, 1912–1949. 5. Taiwan—History—1945– I. Title. II. Title: Chiang Kai- shek and the struggle for modern China. DS777.488.C5T39 2009 951.04′2092—dc22 [B]â 2008040492 To John Taylor, my son, editor, and best friend Contents List of Mapsâ ix Acknowledgmentsâ xi Note on Romanizationâ xiii Prologueâ 1 I Revolution 1. A Neo- Confucian Youthâ 7 2. The Northern Expedition and Civil Warâ 49 3. The Nanking Decadeâ 97 II War of Resistance 4. The Long War Beginsâ 141 5. Chiang and His American Alliesâ 194 6. The China Theaterâ 245 7. Yalta, Manchuria, and Postwar Strategyâ 296 III Civil War 8. Chimera of Victoryâ 339 9. The Great Failureâ 378 viii Contents IV The Island 10. Streams in the Desertâ 411 11. Managing the Protectorâ 454 12. Shifting Dynamicsâ 503 13. Nixon and the Last Yearsâ 547 Epilogueâ 589 Notesâ 597 Indexâ 699 Maps Republican China, 1928â 80–81 China, 1929â 87 Allied Retreat, First Burma Campaign, April–May 1942â 206 China, 1944â 293 Acknowledgments Extensive travel, interviews, and research in Taiwan and China over five years made this book possible. -

Shanghai Urbanism: Reflections from the Outside In

Shanghai Urbanism: Reflections from the Outside In AUTHORED JOINTLY BY: UTE LEHRER PAUL BAILEY CARA CHELLEW ANTHONY J. DIONIGI JUSTIN FOK VICTORIA HO PRISCILLA LAN CHUNG YANG DILYA NIEZOVA NELLY VOLPERT CATHY ZHAO MCRI ii| Page Executive Summary This report was prepared by graduate students who took part in York University’s Critical Urban Planning Workshop, held in Shanghai, China in May of 2015. Instructed by Professor Ute Lehrer, the course was offered in the context of the Major Collaborative Research Initiative on Global Suburbanisms, a multi-researcher project analyzing how the phenomenon of contemporary population growth, which is occurring rapidly in the suburbs, is creating new stresses and opportunities with respect to land, governance, and infrastructure. As a rapidly growing city, Shanghai is exposed to significant challenges with regard to social, economic, environmental, and cultural planning. The workshop was rich in exposure to a myriad of analyses and landscapes, combining lectures, field trips, and meetings with local academics, planners, and activists, our group learned about the successes and challenges facing China’s most populous city. Indeed, this place-based workshop allowed for spontaneous exploration outside of the traditional academic spheres as well, and therefore the reflections shared in this report encompass the more ordinary, experiential side of navigating Shanghai’s metro system, restaurants, streets, and parks in daily life. As a rapidly growing city, Shanghai has achieved numerous successes and faces significant challenges with regard to land-use, social, economic, environmental and cultural planning. As a team of prospective planners with diverse backgrounds, we met with local academics, planners, and activists, and engaged in lectures and field research in Shanghai and nearby towns with the aim to learn from the planning context in Shanghai. -

A RE-EVALUATION of CHIANG KAISHEK's BLUESHIRTS Chinese Fascism in the 1930S

A RE-EVALUATION OF CHIANG KAISHEK’S BLUESHIRTS Chinese Fascism in the 1930s A Dissertation Submitted to the School of Oriental and African Studies of the University of London in Candidacy for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy DOOEUM CHUNG ProQuest Number: 11015717 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 11015717 Published by ProQuest LLC(2018). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106- 1346 2 Abstract Abstract This thesis considers the Chinese Blueshirts organisation from 1932 to 1938 in the context of Chiang Kaishek's attempts to unify and modernise China. It sets out the terms of comparison between the Blueshirts and Fascist organisations in Europe and Japan, indicating where there were similarities and differences of ideology and practice, as well as establishing links between them. It then analyses the reasons for the appeal of Fascist organisations and methods to Chiang Kaishek. Following an examination of global factors, the emergence of the Blueshirts from an internal point of view is considered. As well as assuming many of the characteristics of a Fascist organisation, especially according to the Japanese model and to some extent to the European model, the Blueshirts were in many ways typical of the power-cliques which were already an integral part of Chinese politics. -

Download Here

ISABEL SUN CHAO AND CLAIRE CHAO REMEMBERING SHANGHAI A Memoir of Socialites, Scholars and Scoundrels PRAISE FOR REMEMBERING SHANGHAI “Highly enjoyable . an engaging and entertaining saga.” —Fionnuala McHugh, writer, South China Morning Post “Absolutely gorgeous—so beautifully done.” —Martin Alexander, editor in chief, the Asia Literary Review “Mesmerizing stories . magnificent language.” —Betty Peh-T’i Wei, PhD, author, Old Shanghai “The authors’ writing is masterful.” —Nicholas von Sternberg, cinematographer “Unforgettable . a unique point of view.” —Hugues Martin, writer, shanghailander.net “Absorbing—an amazing family history.” —Nelly Fung, author, Beneath the Banyan Tree “Engaging characters, richly detailed descriptions and exquisite illustrations.” —Debra Lee Baldwin, photojournalist and author “The facts are so dramatic they read like fiction.” —Heather Diamond, author, American Aloha 1968 2016 Isabel Sun Chao and Claire Chao, Hong Kong To those who preceded us . and those who will follow — Claire Chao (daughter) — Isabel Sun Chao (mother) ISABEL SUN CHAO AND CLAIRE CHAO REMEMBERING SHANGHAI A Memoir of Socialites, Scholars and Scoundrels A magnificent illustration of Nanjing Road in the 1930s, with Wing On and Sincere department stores at the left and the right of the street. Road Road ld ld SU SU d fie fie d ZH ZH a a O O ss ss U U o 1 Je Je o C C R 2 R R R r Je Je r E E u s s u E E o s s ISABEL’SISABEL’S o fie fie K K d d d d m JESSFIELD JESSFIELDPARK PARK m a a l l a a y d d y o o o o d d e R R e R R R R a a S S d d SHANGHAISHANGHAI -

How to Review for 185B

How To Review for 185B • Go through your lecture notes – I will put overviews of lectures at my history department’s website – Study guide will be sent out at the end of this week • Go through your textbook • Go through your readings • Extended Office Hour Next Wednesday Lecture 1 Geography of China • Diverse, continent-sided empire • North vs. South • China’s Rivers RIVERS Yellow 黃河 Yangzi 長江 West 西江/珠江 Beijing 北京 Shanghai 上海 Hong Kong (Xianggang) 香港 Lecture 2 Legacies of the Qing Dynasty 1. The Qing Empire (Multi-ethnic Empire) 2. The 1911 Revolution 3. Imperialisms in China 4. Wordlordism and the Early Republic Qing Dynasty Sun Yat-sen 孙中山 Queue- cutting: 1911 The Abdication of Qing • Yuan Shikai – Negotiation between Yuan (on behalf of the Republican) and the Qing State • Abdication of Qing: Feb 12, 1912 • Yuan became the second provisional president Feb 14, 1912 China’s Last Emperor Xuantong 宣统 (Puyi 溥仪) Threats to China Lecture 3 Early Republic 1. The Yuan Shikai Era: a revisionist history 2. Yuan Shikai’s Rule 3. The Beijing Government 4. Warlords in China Yuan Shikai’s Era The New Republic • The New Election – Guomindang – Progressive Party • The Yuan Shikai Era – Challenges –Problems Beijing Government • Chaotic • Constitutional Warlordism • Militarists? • Cliques under Constitutional Government • The Warlord Era Lecture 4 The New Cultural Movement and the May Fourth 1. China and Chinese Culture in Traditional Time 2. The 1911 Revolution and the Change of Political Culture 3. The New Cultural Movement 4. The May Fourth Movement -

Shanghai Sojourners

CHINA RESEARCH MONOGRAPH 40 FM, INSTITUTE OF EAST ASIAN STUDIES ~~ UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA • BERKELEY C(S CENTER FOR CHINESE STUDIES Shanghai Sojourners EDITED BY Frederic Wakeman, Jr., and Wen-hsin Yeh A publication of the Institute of East Asian Studies, University of California at Berkeley. Although the Institute of East Asian Studies is responsible for the selec tion and acceptance of manuscripts in this series, responsibility for the opinions expressed and for the accuracy of statements rests with their authors. Correspondence may be sent to: Ms. Joanne Sandstrom, Managing Editor Institute of East Asian Studies University of California Berkeley, California 94 720 The China Research Monograph series, whose first title appeared in 1967, is one of several publications series sponsored by the Institute of East Asian Studies in conjunction with its constituent units. The others include the Japan Research Monograph series, the Korea Research Monograph series, the Indochina Research Monograph series, and the Research Papers and Policy Studies series. A list of recent publications appears at the back of the book. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Shanghai sojourners I Frederic E. Wakeman, Jr. , Wen-hsin Yeh, editors. p. em. - (China research monograph ; no. 40) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 1-55729-035-0 (paper) : $20.00 l. Shanghai (China)-History. I. Wakeman, Frederic E. II . Yeh, Wen Hsin. III. Series. DS796.5257S57 1992 95l.l'32-dc20 92-70468 CIP Copyright © 1992 by The Regents of the University of California ISBN 1-55729-035-0 Library of Congress Catalog Card Number 92-70468 Printed in the United States of America All rights reserved. -

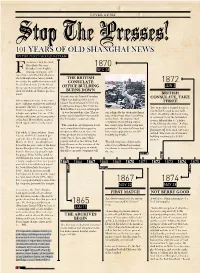

Stop the Presses!

cover story Stop The Presses! 101 YEARS OF OLD SHANGHAI NEWS BY THE THAT’S SHANGHAI TEAM ounded in 1864, the North China Daily News was 1870 Shanghai’s first English- language newspaper and DEC 28 Fone of its most influential. At a time when Shanghai was Asia’s journal- THE BRITISH ism center, the publication was noted CONSULATE 1872 for a balanced voice (for the times), strong reporters and sympathies that OFFICE BUILDING JUN 3 often lay with local Chinese predica- BURNS DOWN ments. BRITISH Shortly after the British Consulate CONSULATE, TAKE It bore witness to some of the city’s Office was built in 1849, it col- THREE most confusing, tumultuous and lurid lapsed. Reconstructed in 1852, the building standing at No. 33 on the moments. The fall of an emperor. Two years after it burned down, a Bund suffered a second catastrophe Violent struggles for power. Triad new British Consulate was built – – it was destroyed in a fire. The re- suit admirably the decimated furni- intrigue and opium. The rise of the which, thankfully, still stands today. porter seems less than impressed by ture and perhaps when everything foreign settlements and crazy parties A ceremony to lay the foundation the Consulate’s temporary digs… settles down, the impoverished at the Astor House Hotel, many of stone is delayed due to “a defect conditions of everything will be which raged until five in the morn- in the Chinese character.” A silver “The consulate and Supreme Court less conspicuous than if going into ing. trowel was ordered from Canton were moved into their respective premises of the extent of these lost, [Guangzhou] to be used, but never temporary offices yesterday, and but present appearances are suf- The whole of these archives – from arrived. -

Treaty-Port English in Nineteenth-Century Shanghai: Speakers, Voices, and Images

Treaty-Port English in Nineteenth-Century Shanghai: Speakers, Voices, and Images Jia Si, Fudan University Abstract This article examines the introduction of English to the treaty port of Shanghai and the speech communities that developed there as a result. English became a sociocultural phenomenon rather than an academic subject when it entered Shanghai in the 1840s, gradually generating various social activities of local Chinese people who lived in the treaty port. Ordinary people picked up a rudimentary knowledge of English along trading streets and through glossary references, and went to private schools to improve their linguistic skills. They used English to communicate with foreigners and as a means to explore a foreign presence dominated by Western material culture. Although those who learned English gained small-scale social mobility in the late nineteenth century, the images of English-speaking Chinese were repeatedly criticized by the literati and official scholars. This paper explores Westerners’ travel accounts, as well as various sources written by the new elite Chinese, including official records and vernacular poems, to demonstrate how English language acquisition brought changes to local people’s daily lives. I argue that treaty-port English in nineteenth-century Shanghai was not only a linguistic medium but, more importantly, a cultural agent of urban transformation. It gradually molded a new linguistic landscape, which at the same time contributed to the shaping of modern Shanghai culture. Introduction The circulation of Western languages through both textual and oral media has enormously affected Chinese society over the past two hundred years. In nineteenth-century China, the English language gradually found a social niche and influenced people’s acceptance of emerging Cross-Currents: East Asian History and Culture Review E-Journal No.