Sample Letter Excerpts Comments by Charles Bright

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Virtual Shanghai

ASIA mmm i—^Zilll illi^—3 jsJ Lane ( Tail Sttjaca, New Uork SOif /iGf/vrs FO, LIN CHARLES WILLIAM WASON COLLECTION Draper CHINA AND THE CHINESE L; THE GIFT OF CHARLES WILLIAM WASON CLASS OF 1876 House 1918 WINE ATJD~SPIRIT MERCHANTS. PROVISION DEALERS. SHIP CHANDLERS. yigents for jfidn\iratty C/jarts- HOUSE BOATS supplied with every re- quisite for Up-Country Trips. LANE CRAWFORD 8 CO., LTD., NANKING ROAD, SHANGHAI. *>*N - HOME USE RULES e All Books subject to recall All borrowers must regis- ter in the library to borrow books fdr home use. All books must be re- turned at end of college year for inspection and repairs. Limited books must be returned within the four week limit and not renewed. Students must return all books before leaving town. Officers should arrange for ? the return of books wanted during their absence from town. Volumes of periodicals and of pamphlets are held in the library as much as possible. For special pur- poses they are given out for a limited time. Borrowers should not use their library privileges for the benefit of other persons Books of special value nd gift books," when the giver wishes it, are not allowed to circulate. Readers are asked to re- port all cases of books marked or mutilated. Do not deface books by marks and writing. - a 5^^KeservaToiioT^^ooni&^by mail or cable. <3. f?EYMANN, Manager, The Leading Hotel of North China. ^—-m——aaaa»f»ra^MS«»» C UniVerS"y Ubrary DS 796.S5°2D22 Sha ^mmmmilS«u,?,?llJff travellers and — — — — ; KELLY & WALSH, Ltd. -

S40410-021-00136-Z.Pdf

Roche Cárcel City Territ Archit (2021) 8:7 https://doi.org/10.1186/s40410-021-00136-z RESEARCH ARTICLE Open Access The spatialization of time and history in the skyscrapers of the twenty-frst century in Shanghai Juan Antonio Roche Cárcel* Abstract This article aims to fnd out to what extent the skyscrapers erected in the late twentieth and early twenty-frst cen- turies, in Shanghai, follow the modern program promoted by the State and the city and how they play an essential role in the construction of the temporary discourse that this modernization entails. In this sense, it describes how the city seeks modernization and in what concrete way it designs a modern temporal discourse. The work fnds out what type of temporal narrative expresses the concentration of these skyscrapers on the two banks of the Huangpu, that of the Bund and that of the Pudong, and fnally, it analyzes the seven most representative and sig- nifcant skyscrapers built in the city in recent years, in order to reveal whether they opt for tradition or modernity, globalization or the local. The work concludes that the past, present and future of Shanghai have been minimized, that its history has been shortened, that it is a liminal site, as its most outstanding skyscrapers, built on the edge of the river and on the border between past and future. For this reason, the author defends that Shanghai, by defn- ing globalization, by being among the most active cities in the construction of skyscrapers, by building more than New York and by building increasingly technologically advanced tall towers, has the possibility to devise a peculiar Chinese modernity, or even deconstruct or give a substantial boost to the general concept of Western modernity. -

Download Here

ISABEL SUN CHAO AND CLAIRE CHAO REMEMBERING SHANGHAI A Memoir of Socialites, Scholars and Scoundrels PRAISE FOR REMEMBERING SHANGHAI “Highly enjoyable . an engaging and entertaining saga.” —Fionnuala McHugh, writer, South China Morning Post “Absolutely gorgeous—so beautifully done.” —Martin Alexander, editor in chief, the Asia Literary Review “Mesmerizing stories . magnificent language.” —Betty Peh-T’i Wei, PhD, author, Old Shanghai “The authors’ writing is masterful.” —Nicholas von Sternberg, cinematographer “Unforgettable . a unique point of view.” —Hugues Martin, writer, shanghailander.net “Absorbing—an amazing family history.” —Nelly Fung, author, Beneath the Banyan Tree “Engaging characters, richly detailed descriptions and exquisite illustrations.” —Debra Lee Baldwin, photojournalist and author “The facts are so dramatic they read like fiction.” —Heather Diamond, author, American Aloha 1968 2016 Isabel Sun Chao and Claire Chao, Hong Kong To those who preceded us . and those who will follow — Claire Chao (daughter) — Isabel Sun Chao (mother) ISABEL SUN CHAO AND CLAIRE CHAO REMEMBERING SHANGHAI A Memoir of Socialites, Scholars and Scoundrels A magnificent illustration of Nanjing Road in the 1930s, with Wing On and Sincere department stores at the left and the right of the street. Road Road ld ld SU SU d fie fie d ZH ZH a a O O ss ss U U o 1 Je Je o C C R 2 R R R r Je Je r E E u s s u E E o s s ISABEL’SISABEL’S o fie fie K K d d d d m JESSFIELD JESSFIELDPARK PARK m a a l l a a y d d y o o o o d d e R R e R R R R a a S S d d SHANGHAISHANGHAI -

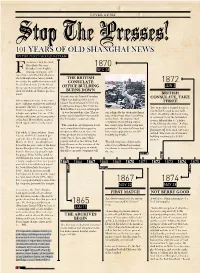

Stop the Presses!

cover story Stop The Presses! 101 YEARS OF OLD SHANGHAI NEWS BY THE THAT’S SHANGHAI TEAM ounded in 1864, the North China Daily News was 1870 Shanghai’s first English- language newspaper and DEC 28 Fone of its most influential. At a time when Shanghai was Asia’s journal- THE BRITISH ism center, the publication was noted CONSULATE 1872 for a balanced voice (for the times), strong reporters and sympathies that OFFICE BUILDING JUN 3 often lay with local Chinese predica- BURNS DOWN ments. BRITISH Shortly after the British Consulate CONSULATE, TAKE It bore witness to some of the city’s Office was built in 1849, it col- THREE most confusing, tumultuous and lurid lapsed. Reconstructed in 1852, the building standing at No. 33 on the moments. The fall of an emperor. Two years after it burned down, a Bund suffered a second catastrophe Violent struggles for power. Triad new British Consulate was built – – it was destroyed in a fire. The re- suit admirably the decimated furni- intrigue and opium. The rise of the which, thankfully, still stands today. porter seems less than impressed by ture and perhaps when everything foreign settlements and crazy parties A ceremony to lay the foundation the Consulate’s temporary digs… settles down, the impoverished at the Astor House Hotel, many of stone is delayed due to “a defect conditions of everything will be which raged until five in the morn- in the Chinese character.” A silver “The consulate and Supreme Court less conspicuous than if going into ing. trowel was ordered from Canton were moved into their respective premises of the extent of these lost, [Guangzhou] to be used, but never temporary offices yesterday, and but present appearances are suf- The whole of these archives – from arrived. -

Treaty-Port English in Nineteenth-Century Shanghai: Speakers, Voices, and Images

Treaty-Port English in Nineteenth-Century Shanghai: Speakers, Voices, and Images Jia Si, Fudan University Abstract This article examines the introduction of English to the treaty port of Shanghai and the speech communities that developed there as a result. English became a sociocultural phenomenon rather than an academic subject when it entered Shanghai in the 1840s, gradually generating various social activities of local Chinese people who lived in the treaty port. Ordinary people picked up a rudimentary knowledge of English along trading streets and through glossary references, and went to private schools to improve their linguistic skills. They used English to communicate with foreigners and as a means to explore a foreign presence dominated by Western material culture. Although those who learned English gained small-scale social mobility in the late nineteenth century, the images of English-speaking Chinese were repeatedly criticized by the literati and official scholars. This paper explores Westerners’ travel accounts, as well as various sources written by the new elite Chinese, including official records and vernacular poems, to demonstrate how English language acquisition brought changes to local people’s daily lives. I argue that treaty-port English in nineteenth-century Shanghai was not only a linguistic medium but, more importantly, a cultural agent of urban transformation. It gradually molded a new linguistic landscape, which at the same time contributed to the shaping of modern Shanghai culture. Introduction The circulation of Western languages through both textual and oral media has enormously affected Chinese society over the past two hundred years. In nineteenth-century China, the English language gradually found a social niche and influenced people’s acceptance of emerging Cross-Currents: East Asian History and Culture Review E-Journal No. -

Shanghai French Concession 1920'S — 1940'S

DOLLAR BUILDING AMERICAN PRESIDENT LINES GREAT NORTHERN FONCIM BUILDING Shanghai French Concession CABLES OFFICE UNION BUILDING HOTEL DES COLONIES SHANGHAI CLUB FRENCH MUNICIPAL AMERICAN McBAIN BUILDING OFFICES AND COTTON METHODIST POLICE STATION, NEW RITZ BAR MONUMENT AUX MORTS (WAR MEMORIAL) MISSION EXCHANGE POSTE DE POLICE JIMMY’S MALLET FRISCO CABARET SEMAPHORE / GUTZLAFF SIGNAL TOWER CHUNG WAI II V BANQUE DE L’INDO-CHINE 1920’s — 1940’s THEATRE BANK E RD A CHINOIS L U TUG & LIGHTER CO. A RUE CHU O MUNICIPAL SCHOOL N D FRENCH MAIL THEATRE PAO SAN E O “BLOOD E R Le Whampoo CHINOIS U U FRENCH CONSULATE ALLEY” N QUAI DE FRANCE I VE E A BUTTERFIELD & SWIRE M PLAZA HOTEL PASSENGER OFFICE T O N RUE LAGUERRE RUE DE LA PORTE DU NORD RUE PALAIS PETIT T CHINA NAVIGATION COMPANY CAFE RUE A DU CONSULAT A II RUE VINCENT MATHIEU LA MISSION U V OFFICE CHINA NAVIGATION RUE DE POST FRENCH RD RUE DISCRY B A A CLUB CO. WHARF U RUE PROTET T N O N ER ED RUE DU MOULIN OLB E H.K. C U RUE TOURARNE LAT TELEPHONE R HOTEL SU BUTTERFIELD WATER TOWER EN ON EXCHANGE V C E & SWIRE A PASSAGE U U DE LA R POMPIERS E D RUE HUE MISSION UE GRAND MONDE / GREAT WORLD R RenMin Road PLACE DU T RUE DES PERES E S T CHATEAU D’EAU CHURCH RUE DE SAIGON B CRISTAL PALACE O N U QUAI DE KIN LEE YUEN L RUE PALIKAO NANKING I E RUE FORMOSE CHINA MARITIME STEAM NAVIGATION CO. -

North-China Herald Office

Journal of Literature and Art Studies, December 2020, Vol. 10, No. 12, 1148-1155 doi: 10.17265/2159-5836/2020.12.010 D DAVID PUBLISHING The Bridge of Chinese and Western Information Exchange in the 19th Century—The Translation of Peking Gazette from North-China Herald Office ZHAO Ying Shanxi University, Taiyuan, China The publication of the translation of Peking Gazette by North-China Herald Office began in 1850 when “The North-China Herald” was first published and finally ended at the end of the 19th century. Peking Gazette is also known and used by more Western readers through the great influence of English newspapers under the jurisdiction of North-China Herald Office. These translations provided western readers with rich knowledge about China in the late Qing Dynasty, enhanced their understanding and understanding of the events from the court to the social customs in the late Qing Dynasty, and on this basis, exerted an important influence on the historical process of Sino-Western relations in the middle and late 19th century. Keywords: Peking Gazette, The North-China Herald, Sino-Western relations In the 19th century, Peking Gazette in China was not only the main information transmission carrier between the court and the populace, but also an important information source for Westerners to learn about the latest developments in the Qing government and Chinese vast inland areas. In the 19th century, Westerners, represented by the British, took great interest in Peking Gazette and carried out a series of important translation activities on it. However, the academic research on Peking Gazette has mostly focused on its Chinese originals at present, which has not yet discussed the translation of Peking Gazette in middle and later period of 19th century. -

UC Berkeley Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UC Berkeley UC Berkeley Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Competing Visions of the Modern: Urban Transformation and Social Change of Changchun, 1932-1957 Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/0149581v Author Liu, Yishi Publication Date 2011 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Competing Visions of the Modern: Urban Transformation and Social Change of Changchun, 1932-1957 By Yishi Liu A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Architecture in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Nezar AlSayyad, Chair Professor Greig Crysler Professor Wen-Hsin Yeh Fall 2011 Abstract Competing Visions of the Modern: Urban Transformation and Social Change of Changchun, 1932-1957 By Yishi Liu Doctor of Philosophy in Architecture University of California, Berkeley Professor Nezar AlSayyad, Chair Examining the urban development and social change of Changchun during the period 1932-1957, this project covers three political regimes in Changchun (the Japanese up to 1945, a 3-year transitional period governed by the Russians and the KMT respectively, and then the Communist after 1948), and explores how political agendas operated and evolved as a local phenomenon in this city. I attempt to reveal connections between the colonial past and socialist “present”. I also aim to reveal both the idiosyncrasies of Japanese colonialism vis-à-vis Western colonialism from the perspective of the built environment, and the similarities and connections of urban construction between the colonial and socialist regime, despite antithetically propagandist banners, to unfold the shared value of anti-capitalist pursuit of exploring new visions of and different paths to the modern. -

Appropriating the West in Late Qing and Early Republican China / Theodore Huters

Tseng 2005.1.17 07:55 7215 Huters / BRINGING THE WORLD HOME / sheet 1 of 384 Bringing the World Home Tseng 2005.1.17 07:55 7215 Huters / BRINGING THE WORLD HOME / sheet 2 of 384 3 of 384 BringingÕ the World HomeÕ Appropriating the West in Late Qing 7215 Huters / BRINGING THE WORLD HOME / sheet and Early Republican China Theodore Huters University of Hawai‘i Press Honolulu Tseng 2005.1.17 07:55 © 2005 University of Hawai‘i Press All rights reserved Printed in the United States of Amer i ca Library of Congress Cataloging- in- Publication Data Huters, Theodore. Bringing the world home : appropriating the West in late Qing and early Republican China / Theodore Huters. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0-8248-2838-0 (hardcover : alk. paper) 1. Chinese literature—20th century—History and criticism. 2. Chinese literature—20th century—Western influences. I. Title. PL2302.H88 2005 895.1’09005—dc22 2004023334 University of Hawai‘i Press books are printed on acid- free paper and meet the guidelines for permanence and durability of the Council on Library Resources. An electronic version of this book is freely available, thanks to the support of libraries working with Knowledge Unlatched. KU is a collaborative initiative designed to make high-quality books open access for the public good. The open-access ISBN for this book is 978-0-8248-7401-8. More information about the initiative and links to the open-access version can be found at www.knowledgeunlatched.org. The open-access version of this book is licensed under Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International (CC BY- NC-ND 4.0), which means that the work may be freely downloaded and shared for non-commercial purposes, provided credit is given to the author. -

{PDF} Shanghai Architecture Ebook, Epub

SHANGHAI ARCHITECTURE PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Anne Warr | 340 pages | 01 Feb 2008 | Watermark Press | 9780949284761 | English | Balmain, NSW, Australia Shanghai architecture: the old and the new | Insight Guides Blog Retrieved 16 July Government of Shanghai. Archived from the original on 5 March Retrieved 10 November Archived from the original on 27 January Archived from the original on 26 May Retrieved 5 August Basic Facts. Shanghai Municipal People's Government. Archived from the original on 3 October Retrieved 19 July Demographia World Urban Areas. Louis: Demographia. Archived PDF from the original on 3 May Retrieved 15 June Shanghai Municipal Statistics Bureau. Archived from the original on 24 March Retrieved 24 March Archived from the original on 9 December Retrieved 8 December Global Data Lab China. Retrieved 9 April Retrieved 27 September Long Finance. Retrieved 8 October Top Universities. Retrieved 29 September Archived from the original on 29 September Archived from the original on 16 April Retrieved 11 January Xinmin Evening News in Chinese. Archived from the original on 5 September Retrieved 12 January Archived from the original on 2 October Retrieved 2 October Topographies of Japanese Modernism. Columbia University Press. Daily Press. Archived from the original on 28 September Retrieved 29 July Archived from the original on 30 August Retrieved 4 July Retrieved 24 November Archived from the original on 16 June Retrieved 26 April Archived from the original on 1 October Retrieved 1 October Archived from the original on 11 September Volume 1. South China Morning Post. Archived from the original on 6 May Retrieved 2 May Office of Shanghai Chronicles. -

Urban Transformation and Social Change of Changchun, 1932-1957

Competing Visions of the Modern: Urban Transformation and Social Change of Changchun, 1932-1957 By Yishi Liu A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Architecture in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Nezar AlSayyad, Chair Professor Greig Crysler Professor Wen-Hsin Yeh Fall 2011 Abstract Competing Visions of the Modern: Urban Transformation and Social Change of Changchun, 1932-1957 By Yishi Liu Doctor of Philosophy in Architecture University of California, Berkeley Professor Nezar AlSayyad, Chair Examining the urban development and social change of Changchun during the period 1932-1957, this project covers three political regimes in Changchun (the Japanese up to 1945, a 3-year transitional period governed by the Russians and the KMT respectively, and then the Communist after 1948), and explores how political agendas operated and evolved as a local phenomenon in this city. I attempt to reveal connections between the colonial past and socialist “present”. I also aim to reveal both the idiosyncrasies of Japanese colonialism vis-à-vis Western colonialism from the perspective of the built environment, and the similarities and connections of urban construction between the colonial and socialist regime, despite antithetically propagandist banners, to unfold the shared value of anti-capitalist pursuit of exploring new visions of and different paths to the modern. The first three chapters relate to colonial period (1932-1945), each exploring one facet of the idiosyncrasies of Japanese colonialism in relation to Changchun’s urbanism. Chapter One deals with the idiosyncrasies of Japanese colonialism as manifested in planning Changchun are the subject of the next chapter. -

BRIEF HISTORY of KOREA —A Bird's-Eyeview—

BRIEF HISTORY OF KOREA —A Bird's-EyeView— Young Ick Lew with an afterword by Donald P. Gregg The Korea Society New York The Korea Society is a private, nonprofit, nonpartisan, 501(c)(3) organization with individual and corporate members that is dedicated solely to the promotion of greater awareness, understanding and cooperation between the people of the United States and Korea. In pursuit of its mission, the Society arranges programs that facilitate dis- cussion, exchanges and research on topics of vital interest to both countries in the areas of public policy, business, education, intercultural relations and the arts. Funding for these programs is derived from contributions, endowments, grants, membership dues and program fees. From its base in New York City, the Society serves audiences across the country through its own outreach efforts and by forging strategic alliances with counterpart organizations in other cities throughout the United States as well as in Korea. The Korea Society takes no institutional position on policy issues and has no affiliation with the U.S. government. All statements of fact and expressions of opinion contained in all its publications are the sole responsibility of the author or authors. For further information about The Korea Society, please write The Korea Society, 950 Third Avenue, 8th Floor, New York, NY 10022, or e-mail: [email protected]. Visit our website at www.koreasociety.org. Copyright © 2000 by Young Ick Lew and The Korea Society All rights reserved. Published 2000 ISBN 1-892887-00-7 Printed in the United States of America Every effort has been made to locate the copyright holders of all copyrighted materials and secure the necessary permission to reproduce them.