UNIVERSITY of CALIFORNIA, IRVINE Shanghai's Wandering

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Journal of East Asian Libraries, No. 165, October 2017

Journal of East Asian Libraries Volume 2017 | Number 165 Article 1 10-2017 Journal of East Asian Libraries, No. 165, October 2017 Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/jeal BYU ScholarsArchive Citation (2017) "Journal of East Asian Libraries, No. 165, October 2017," Journal of East Asian Libraries: Vol. 2017 : No. 165 , Article 1. Available at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/jeal/vol2017/iss165/1 This Full Issue is brought to you for free and open access by the All Journals at BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of East Asian Libraries by an authorized editor of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Journal of East Asian Libraries Journal of the Council on East Asian Libraries No. 165, October 2017 CONTENTS From the President 3 Essay A Tribute to John Yung-Hsiang Lai 4 Eugene W. Wu Peer-Review Articles An Overview of Predatory Journal Publishing in Asia 8 Jingfeng Xia, Yue Li, and Ping Situ Current Situation and Challenges of Building a Japanese LGBTQ Ephemera Collection at Yale Haruko Nakamura, Yoshie Yanagihara, and Tetsuyuki Shida 19 Using Data Visualization to Examine Translated Korean Literature 36 Hyokyoung Yi and Kyung Eun (Alex) Hur Managing Changes in Collection Development 45 Xiaohong Chen Korean R me for the Library of Congress to Stop Promoting Mccune-Reischauer and Adopt the Revised Romanization Scheme? 57 Chris Dollŏmaniz’atiŏn: Is It Finally Ti Reports Building a “One- 85 Paul W. T. Poon hour Library Circle” in China’s Pearl River Delta Region with the Curator of the Po Leung Kuk Museum 87 Patrick Lo and Dickson Chiu Interview 1 Web- 93 ProjectCollecting Report: Social Media Data from the Sina Weibo Api 113 Archiving Chinese Social Media: Final Project Report New Appointments 136 Book Review 137 Yongyi Song, Editor-in-Chief:China and the Maoist Legacy: The 50th Anniversary of the Cultural Revolution文革五十年:毛泽东遗产和当代中国. -

Shanghai, China's Capital of Modernity

SHANGHAI, CHINA’S CAPITAL OF MODERNITY: THE PRODUCTION OF SPACE AND URBAN EXPERIENCE OF WORLD EXPO 2010 by GARY PUI FUNG WONG A thesis submitted to The University of Birmingham for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOHPY School of Government and Society Department of Political Science and International Studies The University of Birmingham February 2014 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. ABSTRACT This thesis examines Shanghai’s urbanisation by applying Henri Lefebvre’s theories of the production of space and everyday life. A review of Lefebvre’s theories indicates that each mode of production produces its own space. Capitalism is perpetuated by producing new space and commodifying everyday life. Applying Lefebvre’s regressive-progressive method as a methodological framework, this thesis periodises Shanghai’s history to the ‘semi-feudal, semi-colonial era’, ‘socialist reform era’ and ‘post-socialist reform era’. The Shanghai World Exposition 2010 was chosen as a case study to exemplify how urbanisation shaped urban experience. Empirical data was collected through semi-structured interviews. This thesis argues that Shanghai developed a ‘state-led/-participation mode of production’. -

Anonymous Birth Law Saves Babies—Optimization, Sustainability and Public Awareness

Arch Womens Ment Health (2016) 19:291–297 DOI 10.1007/s00737-015-0567-3 ORIGINAL ARTICLE Anonymous birth law saves babies—optimization, sustainability and public awareness Chryssa Grylli1 & Ian Brockington2 & Christian Fiala3 & Mercedes Huscsava4 & Thomas Waldhoer5 & Claudia M. Klier1 Received: 5 April 2015 /Accepted: 30 July 2015 /Published online: 13 August 2015 # Springer-Verlag Wien 2015 Abstract The aims of this study are to assess the impact of neonaticides. The subsequent significantly decreasing num- Austria’s anonymous birth law from the time relevant statisti- bers of anonymous births with an accompanying increase of cal records are available and to evaluate the use of hatches neonaticides represents additional evidence for the effective- versus anonymous hospital delivery. This study is a complete ness of the measure. census of police-reported neonaticides (1975–2012) as well as anonymous births including baby hatches in Austria during Keywords Anonymous birth . Baby hatches . Neonaticide . 2002–2012. The time trends of neonaticide rates, anonymous Child abandonment legislation births and baby hatches were analysed by means of Poisson and logistic regression model. Predicted and observed rates were derived and compared using a Bayesian Poisson regres- sion model. Predicted numbers of neonaticides for the period Introduction of the active awareness campaign, 2002–2004, were more than three times larger than the observed number (p= The day of birth is the day in which an individual runs the 0.0067). Of the 365 women who benefitted from this legisla- highest risk of being murdered. The term ‘neonaticide’ has tion, only 11.5 % chose to put their babies in a baby hatch. -

Download Press

SYNOPSIS Vienna, 2001. CARLA, an Austrian woman in her late twenties and bulimic, became pregnant unintentionally and lives as a single mother under very precarious cir- cumstances. She struggles to have the strength to take responsibility - financially and psychologically - for the baby. While searching for the child’s father, Carla meets in her former favorite karaoke bar a non-binary person from Argentina who is dressed as an ASTRONAUT. The two social outcasts establish a closeness in a short time that some people cannot achieve in years in a confined space. The encounter with the Astronaut gives Carla a new per- spective on her reality and the courage to make the most important decision of her life. DIRECTOR’S MARIANO CABACO NOTES The human brain automatically organizes people and things into categories to make the world easier to understand for themselves. Discrimination, misunderstandings and fears are mostly the result of this. ASTRONAUTS deals with questions that are drastic and still hard to make for women today. When the external circumstances are precarious, a lot of feelings of guilt come up when having a child. The first baby hatch was launched in Vienna in 2001 to help parents in such hopeless situations. Being able to bring your child to such a safe place, where they are well looked after, is an important socio-political and women’s rights achievement that is just as important today as it was 20 years ago. Two strangers from different cultures meet in absurd circumstances - a Karaoke Bar in Vienna-, as out- casts of society. But their cultural differences give them the space to change their perspective on their personal realities. -

Shanghai Before Nationalism Yexiaoqing

East Asian History NUMBER 3 . JUNE 1992 THE CONTINUATION OF Papers on Fa r EasternHistory Institute of Advanced Studies Australian National University Editor Geremie Barme Assistant Editor Helen 1.0 Editorial Board John Clark Igor de Rachewiltz Mark Elvin (Convenor) Helen Hardacre John Fincher Colin Jeffcott W.J.F. Jenner 1.0 Hui-min Gavan McCormack David Marr Tessa Morris-Suzuki Michael Underdown Business Manager Marion Weeks Production Oahn Collins & Samson Rivers Design Maureen MacKenzie, Em Squared Typographic Design Printed by Goanna Print, Fyshwick, ACT This is the second issue of EastAsian History in the series previously entitled Papers on Far Eastern History. The journal is published twice a year. Contributions to The Editor, EastAsian History Division of Pacific and Asian History, Research School of Pacific Studies Australian National University, Canberra ACT 2600, Australia Phone +61-6-2493140 Fax +61-6-2571893 Subscription Enquiries Subscription Manager, East Asian History, at the above address Annual Subscription Rates Australia A$45 Overseas US$45 (for two issues) iii CONTENTS 1 Politics and Power in the Tokugawa Period Dani V. Botsman 33 Shanghai Before Nationalism YeXiaoqing 53 'The Luck of a Chinaman' : Images of the Chinese in Popular Australian Sayings Lachlan Strahan 77 The Interactionistic Epistemology ofChang Tung-sun Yap Key-chong 121 Deconstructing Japan' Amino Yoshthtko-translat ed by Gavan McCormack iv Cover calligraphy Yan Zhenqing ���Il/I, Tang calligrapher and statesman Cover illustration Kazai*" -a punishment -

Virtual Shanghai

ASIA mmm i—^Zilll illi^—3 jsJ Lane ( Tail Sttjaca, New Uork SOif /iGf/vrs FO, LIN CHARLES WILLIAM WASON COLLECTION Draper CHINA AND THE CHINESE L; THE GIFT OF CHARLES WILLIAM WASON CLASS OF 1876 House 1918 WINE ATJD~SPIRIT MERCHANTS. PROVISION DEALERS. SHIP CHANDLERS. yigents for jfidn\iratty C/jarts- HOUSE BOATS supplied with every re- quisite for Up-Country Trips. LANE CRAWFORD 8 CO., LTD., NANKING ROAD, SHANGHAI. *>*N - HOME USE RULES e All Books subject to recall All borrowers must regis- ter in the library to borrow books fdr home use. All books must be re- turned at end of college year for inspection and repairs. Limited books must be returned within the four week limit and not renewed. Students must return all books before leaving town. Officers should arrange for ? the return of books wanted during their absence from town. Volumes of periodicals and of pamphlets are held in the library as much as possible. For special pur- poses they are given out for a limited time. Borrowers should not use their library privileges for the benefit of other persons Books of special value nd gift books," when the giver wishes it, are not allowed to circulate. Readers are asked to re- port all cases of books marked or mutilated. Do not deface books by marks and writing. - a 5^^KeservaToiioT^^ooni&^by mail or cable. <3. f?EYMANN, Manager, The Leading Hotel of North China. ^—-m——aaaa»f»ra^MS«»» C UniVerS"y Ubrary DS 796.S5°2D22 Sha ^mmmmilS«u,?,?llJff travellers and — — — — ; KELLY & WALSH, Ltd. -

Bourgeois Shanghai: Wang Anyi’S Novel of Nostalgia Wittenberg University

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln The hinC a Beat Blog Archive 2008-2012 China Beat Archive 7-14-2008 Bourgeois Shanghai: Wang Anyi’s Novel of Nostalgia Wittenberg University Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/chinabeatarchive Part of the Asian History Commons, Asian Studies Commons, Chinese Studies Commons, and the International Relations Commons Wittenberg University, "Bourgeois Shanghai: Wang Anyi’s Novel of Nostalgia" (2008). The China Beat Blog Archive 2008-2012. 157. http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/chinabeatarchive/157 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the China Beat Archive at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in The hinC a Beat Blog Archive 2008-2012 by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Bourgeois Shanghai: Wang Anyi’s Novel of Nostalgia July 14, 2008 in Watching the China Watchers by The China Beat | No comments After the recent publication of a translation of Wang Anyi’s 1995 novel A Song of Everlasting Sorrow, we asked Howard Choy to reflect on the novel’s contents and importance. Below, Choy draws on his recently published work on late twentieth century Chinese fiction to contextualize Wang’s Shanghai story. By Howard Y. F. Choy Among all the major cities in China, Shanghai has become the most popular in recent academic research and creative writings. This is partly a consequence of its resuscitation under Deng Xiaoping’s (1904-1997) intensified economic reforms in the 1990s, and partly due to its unique experience during one hundred years (1843-1943) of colonization and the concomitant modernization that laid the foundation for the new Shanghai we see today. -

Openness in International Adoption

Texas A&M University School of Law Texas A&M Law Scholarship Faculty Scholarship 3-2015 Openness in International Adoption Malinda L. Seymore Texas A&M University School of Law, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.tamu.edu/facscholar Part of the Family Law Commons, and the International Law Commons Recommended Citation Malinda L. Seymore, Openness in International Adoption, 46 Colum. Hum. Rts. L. Rev. 163 (2015). Available at: https://scholarship.law.tamu.edu/facscholar/707 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Texas A&M Law Scholarship. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Scholarship by an authorized administrator of Texas A&M Law Scholarship. For more information, please contact [email protected]. OPENNESS IN INTERNATIONAL ADOPTION Malinda L. Seymore* ABSTRACT After a long history of secrecy in domestic adoption in the United States, there is a robust trend toward openness. That is, however, not the case with internationaladoption. The recent growth in international adoption has been spurred, at least in part, by the desire of adoptive parents to return to closed, confidential adoptions where the identity of the birth mother is secret and there is no ongoing contact with her. There is, however, an emergent interest in increased openness in internationaladoption, spurred by the success of domestic open adoptions, health concerns when an adoptee's genetic history is important, psychological issues relating to identity in adoptees, and concern that the international adoption might have been corrupt. International adoptive families who were once happy to avoid birth parent involvement have begun to seek them out. -

Some Pioneer Families of Wisconsin

.. .... -. ,. .. ,. ......i ......- -- SOME PIONEER FAMILIES OF WISCONSIN - An Index - edited by Betty Patterson A Bicentennial Project of the Wisconsin State Genealogical Society, Inc. Madison, Wisconsin 1977 Copyright@1977, Wisconsin State Genealogical Society, Inc. Library of Congress Cata log Card No.: 77-11739 PUBLISHED BY THE WISCONSIN STATE c;:+ICAL SOCIETY INC. PRINTED IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA BY .•.• tht: PRINl'shop OF DIXON, ILLINOIS ' ' This little book is dedicated to those who have sensed the thrill of unraveling their family mystery stories and the quiet satisfaction that comes from traveling vicariously with generations of grandparents long unknown. It is hoped that, at least in Wisconsin, it may make their searching a little easier. ERRATA II p. 2, Line 31 should read: "Spelling was an imprecise art in times past, Line 38 should read: 11 Jorndt, while the other (Fern Smith, #1815 .... 11 p. 126, Lines 70, 71, & 72, the spouses in column 4 should be Ann Eliza Taylor, George J. Beach, and Edward L. Myers. Background of the Pioneer and Century Certificate Project Even before the impetus of the Bicentennial year and the appearance of Alex Haley's Roots, more and more people were becoming interested in genealogy. Fifty years ago, the word was apt to mean an exercise aimed at qualifying for membership in an exclusive society. Today, its meaning has broadened to acconnnodate an increased awareness of the value of family and national heritages. Realization has come, too, that in a time of great social change, the knowledge of these--placing the individual, as it were, in a context--can stabilize and illuminate the sense of self. -

Conflict, Community and Crime in Fin-De-Siècle Sichuan

CONFLICT, COMMUNITY AND CRIME IN FIN-DE-SIÈCLE SICHUAN A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY AND THE COMMITTEE ON GRADUATE STUDIES OF STANFORD UNIVERSITY IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY QUINN DOYLE JAVERS MAY 2012 © 2012 by Quinn Doyle Javers. All Rights Reserved. Re-distributed by Stanford University under license with the author. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution- Noncommercial 3.0 United States License. http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/us/ This dissertation is online at: http://purl.stanford.edu/gr339jp1011 ii I certify that I have read this dissertation and that, in my opinion, it is fully adequate in scope and quality as a dissertation for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Matthew Sommer, Primary Adviser I certify that I have read this dissertation and that, in my opinion, it is fully adequate in scope and quality as a dissertation for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Karen Wigen I certify that I have read this dissertation and that, in my opinion, it is fully adequate in scope and quality as a dissertation for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Christian Henriot Approved for the Stanford University Committee on Graduate Studies. Patricia J. Gumport, Vice Provost Graduate Education This signature page was generated electronically upon submission of this dissertation in electronic format. An original signed hard copy of the signature page is on file in University Archives. iii Abstract The 350 legal cases from the ming’an [“cases of unnatural death”] category of the Ba County archive that survive from the final decade of the nineteenth century create a textured picture of social life and state-society relations at the grassroots near the end of the Qing Dynasty (1644-1912). -

1.9 Alternatives for Dredging

Public Disclosure Authorized ENVIRONMENTAL AND SOCIAL IMPACT ASSESSMENT EXECUTIVE SUMMARY FOR Public Disclosure Authorized HEZHOU URBAN WATER INFRASTRUCTURE AND ENVIRONMENT IMPROVEMENT PROJECT Public Disclosure Authorized Prepared by Guangxi Zhengze Environmental Protection Technology Co., Ltd. Entrusted by Public Disclosure Authorized Hezhou World Bank Loan Project Management Office November 2017 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. INTRODUCTION .................................................................................................. 1 1.1 Background .................................................................................................. 1 1.2 Environmental Assessment Process and Legal Framework ........................ 1 1.3 Scope of EA and Sensitive Receptors .......................................................... 3 2. PROJECT DESCRIPTION ..................................................................................... 4 3. ENVIRONMENTAL AND SOCIAL BASELINE ................................................. 7 3.1 Physical Environment .................................................................................. 7 3.2 Socio-economic Context.............................................................................. 7 3.3 Ecological Environment .............................................................................. 8 3.4 Environmental Quality ................................................................................ 8 4. ANALYSIS OF ALTERNATIVES ........................................................................ -

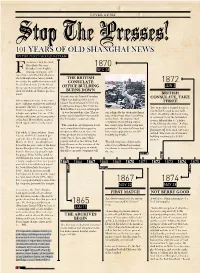

Stop the Presses!

cover story Stop The Presses! 101 YEARS OF OLD SHANGHAI NEWS BY THE THAT’S SHANGHAI TEAM ounded in 1864, the North China Daily News was 1870 Shanghai’s first English- language newspaper and DEC 28 Fone of its most influential. At a time when Shanghai was Asia’s journal- THE BRITISH ism center, the publication was noted CONSULATE 1872 for a balanced voice (for the times), strong reporters and sympathies that OFFICE BUILDING JUN 3 often lay with local Chinese predica- BURNS DOWN ments. BRITISH Shortly after the British Consulate CONSULATE, TAKE It bore witness to some of the city’s Office was built in 1849, it col- THREE most confusing, tumultuous and lurid lapsed. Reconstructed in 1852, the building standing at No. 33 on the moments. The fall of an emperor. Two years after it burned down, a Bund suffered a second catastrophe Violent struggles for power. Triad new British Consulate was built – – it was destroyed in a fire. The re- suit admirably the decimated furni- intrigue and opium. The rise of the which, thankfully, still stands today. porter seems less than impressed by ture and perhaps when everything foreign settlements and crazy parties A ceremony to lay the foundation the Consulate’s temporary digs… settles down, the impoverished at the Astor House Hotel, many of stone is delayed due to “a defect conditions of everything will be which raged until five in the morn- in the Chinese character.” A silver “The consulate and Supreme Court less conspicuous than if going into ing. trowel was ordered from Canton were moved into their respective premises of the extent of these lost, [Guangzhou] to be used, but never temporary offices yesterday, and but present appearances are suf- The whole of these archives – from arrived.