Conflict, Community and Crime in Fin-De-Siècle Sichuan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Effect of Marine Bacillus BC-2 on the Health-Beneficial Ingredients of Flavor Liquor

Food and Nutrition Sciences, 2019, 10, 606-612 http://www.scirp.org/journal/fns ISSN Online: 2157-9458 ISSN Print: 2157-944X Effect of Marine Bacillus BC-2 on the Health-Beneficial Ingredients of Flavor Liquor Yueming Li*, Jianchun Xu, Zhimei Xu Qingdao Langyatai Group Co., Ltd., Qingdao, China How to cite this paper: Li, Y.M., Xu, J.C. Abstract and Xu, Z.M. (2019) Effect of Marine Ba- cillus BC-2 on the Health-Beneficial Ingre- The main aroma component of Luzhou-flavor Liquor is ethyl caproate, which dients of Flavor Liquor. Food and Nutrition is combined with appropriate amount of ethyl butyrate, ethyl acetate, ethyl Sciences, 10, 606-612. lactate and so on. By adding the marine bacillus BC-2 (Accession number: https://doi.org/10.4236/fns.2019.106044 MK811408) to substrate sludge, the bacillus complex bacterial liquid (pit Mud Received: March 27, 2019 Functional Bacterial liquid) has been modified. The complex bacterial liquid Accepted: June 11, 2019 was used in the production of Luzhou-flavor Liquor and it dramatically pro- Published: June 14, 2019 moted the content of health-beneficial ingredients in the new workshop. These results demonstrated that the marine bacillus BC-2 can effectively im- Copyright © 2019 by author(s) and prove the quality and health benefit of Luzhou-flavor Liquor. Scientific Research Publishing Inc. This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International Keywords License (CC BY 4.0). Luzhou-Flavor Liquor, Marine Bacillus BC-2, Flavoring Components http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ Open Access 1. Introduction In China, Luzhou-flavor Liquor is the most widely used Luzhou-flavor Liquor in social intercourse and its taste is closely related to the quality of pit mud. -

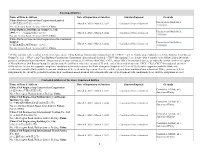

Sanctioned Entities Name of Firm & Address Date

Sanctioned Entities Name of Firm & Address Date of Imposition of Sanction Sanction Imposed Grounds China Railway Construction Corporation Limited Procurement Guidelines, (中国铁建股份有限公司)*38 March 4, 2020 - March 3, 2022 Conditional Non-debarment 1.16(a)(ii) No. 40, Fuxing Road, Beijing 100855, China China Railway 23rd Bureau Group Co., Ltd. Procurement Guidelines, (中铁二十三局集团有限公司)*38 March 4, 2020 - March 3, 2022 Conditional Non-debarment 1.16(a)(ii) No. 40, Fuxing Road, Beijing 100855, China China Railway Construction Corporation (International) Limited Procurement Guidelines, March 4, 2020 - March 3, 2022 Conditional Non-debarment (中国铁建国际集团有限公司)*38 1.16(a)(ii) No. 40, Fuxing Road, Beijing 100855, China *38 This sanction is the result of a Settlement Agreement. China Railway Construction Corporation Ltd. (“CRCC”) and its wholly-owned subsidiaries, China Railway 23rd Bureau Group Co., Ltd. (“CR23”) and China Railway Construction Corporation (International) Limited (“CRCC International”), are debarred for 9 months, to be followed by a 24- month period of conditional non-debarment. This period of sanction extends to all affiliates that CRCC, CR23, and/or CRCC International directly or indirectly control, with the exception of China Railway 20th Bureau Group Co. and its controlled affiliates, which are exempted. If, at the end of the period of sanction, CRCC, CR23, CRCC International, and their affiliates have (a) met the corporate compliance conditions to the satisfaction of the Bank’s Integrity Compliance Officer (ICO); (b) fully cooperated with the Bank; and (c) otherwise complied fully with the terms and conditions of the Settlement Agreement, then they will be released from conditional non-debarment. If they do not meet these obligations by the end of the period of sanction, their conditional non-debarment will automatically convert to debarment with conditional release until the obligations are met. -

Archaeological Observation on the Exploration of Chu Capitals

Archaeological Observation on the Exploration of Chu Capitals Wang Hongxing Key words: Chu Capitals Danyang Ying Chenying Shouying According to accurate historical documents, the capi- In view of the recent research on the civilization pro- tals of Chu State include Danyang 丹阳 of the early stage, cess of the middle reach of Yangtze River, we may infer Ying 郢 of the middle stage and Chenying 陈郢 and that Danyang ought to be a central settlement among a Shouying 寿郢 of the late stage. Archaeologically group of settlements not far away from Jingshan 荆山 speaking, Chenying and Shouying are traceable while with rice as the main crop. No matter whether there are the locations of Danyang and Yingdu 郢都 are still any remains of fosses around the central settlement, its oblivious and scholars differ on this issue. Since Chu area must be larger than ordinary sites and be of higher capitals are the political, economical and cultural cen- scale and have public amenities such as large buildings ters of Chu State, the research on Chu capitals directly or altars. The site ought to have definite functional sec- affects further study of Chu culture. tions and the cemetery ought to be divided into that of Based on previous research, I intend to summarize the aristocracy and the plebeians. The relevant docu- the exploration of Danyang, Yingdu and Shouying in ments and the unearthed inscriptions on tortoise shells recent years, review the insufficiency of the former re- from Zhouyuan 周原 saying “the viscount of Chu search and current methods and advance some personal (actually the ruler of Chu) came to inform” indicate that opinion on the locations of Chu capitals and later explo- Zhou had frequent contact and exchange with Chu. -

Discovering Discrepancies in Numerical Libraries

Discovering Discrepancies in Numerical Libraries Jackson Vanover Xuan Deng Cindy Rubio-González University of California, Davis University of California, Davis University of California, Davis United States of America United States of America United States of America [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] ABSTRACT libraries aim to offer a certain level of correctness and robustness in Numerical libraries constitute the building blocks for software appli- their algorithms. Specifically, a discrete numerical algorithm should cations that perform numerical calculations. Thus, it is paramount not diverge from the continuous analytical function it implements that such libraries provide accurate and consistent results. To that for its given domain. end, this paper addresses the problem of finding discrepancies be- Extensive testing is necessary for any software that aims to be tween synonymous functions in different numerical libraries asa correct and robust; in all application domains, software testing means of identifying incorrect behavior. Our approach automati- is often complicated by a deficit of reliable test oracles and im- cally finds such synonymous functions, synthesizes testing drivers, mense domains of possible inputs. Testing of numerical software and executes differential tests to discover meaningful discrepan- in particular presents additional difficulties: there is a lack of stan- cies across numerical libraries. We implement our approach in a dards for dealing with inevitable numerical errors, and the IEEE 754 tool named FPDiff, and provide an evaluation on four popular nu- Standard [1] for floating-point representations of real numbers in- merical libraries: GNU Scientific Library (GSL), SciPy, mpmath, and herently introduces imprecision. As a result, bugs are commonplace jmat. -

A Data Compression Algorithm Based on Adaptive Huffman Code for Wireless Sensor Networks

2011 Fourth International Conference on Intelligent Computation Technology and Automation (ICICTA 2011) Shenzhen, China 28 – 29 March 2011 Volume 1 Pages 1-618 IEEE Catalog Number: CFP1188E-PRT ISBN: 978-1-61284-289-9 1/4 2011 Fourth International Conference on Intelligent Computation Technology and Automation ICICTA 2011 Table of Contents Volume - 1 Preface - Volume 1.....................................................................................................................................................xxv Conference Committees - Volume 1.......................................................................................................................xxvi Reviewers - Volume 1.............................................................................................................................................xxviii Session 1: Advanced Comptation Theory and Applications A Data Compression Algorithm Based on Adaptive Huffman Code for Wireless Sensor Networks .............................................................................................................................................................3 Mo Yuanbin, Qiu Yubing, Liu Jizhong, and Ling Yanxia A Genetic Algorithm for Solving Weak Nonlinear Bilevel Programming Problems ....................................................7 Yulan Xiao and Hecheng Li A Layering Learning Routing Algorithm of WSNs Based on ADS Approach ............................................................10 Wang Zhaoqing and Zhong Sheng A Load Distribution Optimization among -

Lihua Xu, Ph.D

Curriculum Vitae LIHUA XU, PH.D. 400 Palisades Circle, Apt. 202 Asheville, NC 28803 Email: [email protected] Cell: 407-808-2675 EDUCATION Ph.D. December 2009 Oklahoma State University - Stillwater, OK Specialization: Research and Evaluation, Educational Psychology Certificate: TESOL / Linguistics Dissertation: Measurement Invariance of the Inventory of School Motivation across Chinese and American College Students M.A. 2003 Sun Yat-sen University - Guangdong, China TESOL / Linguistics B.A. 1998 Sichuan University - Sichuan, China English ACADEMIC EMPLOYMENT 2017 – present Assistant Professor in Educational Research Western Carolina University, College of Education and Allied Professions Department of Human Services, Educational Leadership Ed.D. program 2010-2017 Lecturer and Statistics Lab Coordinator University of Central Florida, College of Education and Human Performance, Department of Educational and Human Sciences, Methodology Measurement and Analysis Courses Taught 2017- present Western Carolina University ⋅ Multiple Regression (EDL 793) ⋅ Design and Analysis of Educational Research (EDRS 802) ⋅ Data Representation (EDRS 805) ⋅ Classroom Assessment for Student Learning (EDRS 709) ⋅ Methods of Research (EDRS 602) 2010-2017 University of Central Florida, Educational and Human Sciences – Orlando, FL ⋅ Fundamentals of Graduate Research in Education (EDF 6481) ⋅ Measurement and Evaluation in Education (EDF 6432) ⋅ Statistics for Educational Data (EDF 6401) ⋅ Mixed Methods for Evaluation (EDF 6464) 2003-2009 Oklahoma State University, Research and Evaluation – Stillwater, OK Research Design and Methodology (REMS 5013) Oklahoma State University, English Department – Stillwater, OK International Composition I (ENGL 1113) International Composition II (ENGL 1223) Peer-Reviewed Journal Articles (13 articles) * Indicates invited 1. Hayles, O., Xu, L., & Edwards, O. W. (2018). Family structures, family relationship, and children’s perceptions of life satisfaction. -

Risk of 2019 Novel Coronavirus Importations Throughout China Prior to the Wuhan Quarantine

medRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.01.28.20019299; this version posted February 3, 2020. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted medRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under a CC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 International license . Title: Risk of 2019 novel coronavirus importations throughout China prior to the Wuhan quarantine 1,+ 2,+ 2 3 4 Authors: Zhanwei Du , Lin Wang , Simon Cauchemez , Xiaoke Xu , Xianwen Wang , 5 1,6* Benjamin J. Cowling , and Lauren Ancel Meyers Affiliations: 1. The University of Texas at Austin, Austin, Texas 78712, The United States of America 2. Institut Pasteur, 28 rue du Dr Roux, Paris 75015, France 3. Dalian Minzu University, Dalian 116600, China. 4. Dalian University of Technology, Dalian 116024, China 5. The University of Hong Kong, Sassoon Rd 7, Hong Kong SAR, China 6. Santa Fe Institute, Santa Fe, New Mexico, The United States of America Corresponding author: Lauren Ancel Meyers Corresponding author email: [email protected] + These first authors contributed equally to this article Abstract On January 23, 2020, China quarantined Wuhan to contain an emerging coronavirus (2019-nCoV). Here, we estimate the probability of 2019-nCoV importations from Wuhan to 369 cities throughout China before the quarantine. The expected risk exceeds 50% in 128 [95% CI 75 186] cities, including five large cities with no reported cases by January 26th. NOTE: This preprint reports new research that has not been certified by peer review and should not be used to guide clinical practice. -

(And Misreading) the Draft Constitution in China, 1954

Textual Anxiety Reading (and Misreading) the Draft Constitution in China, 1954 ✣ Neil J. Diamant and Feng Xiaocai In 1927, Mao Zedong famously wrote that a revolution is “not the same as inviting people to dinner” and is instead “an act of violence whereby one class overthrows the authority of another.” From the establishment of the People’s Republic of China (PRC) in 1949 until Mao’s death in 1976, his revolutionary vision became woven into the fabric of everyday life, but few years were as violent as the early 1950s.1 Rushing to consolidate power after finally defeating the Nationalist Party (Kuomintang, or KMT) in a decades- long power struggle, the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) threatened the lives and livelihood of millions. During the Land Reform Campaign (1948– 1953), landowners, “local tyrants,” and wealthier villagers were targeted for repression. In the Campaign to Suppress Counterrevolutionaries in 1951, the CCP attacked former KMT activists, secret society and gang members, and various “enemy agents.”2 That same year, university faculty and secondary school teachers were forced into “thought reform” meetings, and businessmen were harshly investigated during the “Five Antis” Campaign in 1952.3 1. See Mao’s “Report of an Investigation into the Peasant Movement in Hunan,” in Stuart Schram, ed., The Political Thought of Mao Tse-tung (New York: Praeger, 1969), pp. 252–253. Although the Cultural Revolution (1966–1976) was extremely violent, the death toll, estimated at roughly 1.5 million, paled in comparison to that of the early 1950s. The nearest competitor is 1958–1959, during the Great Leap Forward. -

Preparing the Shaanxi-Qinling Mountains Integrated Ecosystem Management Project (Cofinanced by the Global Environment Facility)

Technical Assistance Consultant’s Report Project Number: 39321 June 2008 PRC: Preparing the Shaanxi-Qinling Mountains Integrated Ecosystem Management Project (Cofinanced by the Global Environment Facility) Prepared by: ANZDEC Limited Australia For Shaanxi Province Development and Reform Commission This consultant’s report does not necessarily reflect the views of ADB or the Government concerned, and ADB and the Government cannot be held liable for its contents. (For project preparatory technical assistance: All the views expressed herein may not be incorporated into the proposed project’s design. FINAL REPORT SHAANXI QINLING BIODIVERSITY CONSERVATION AND DEMONSTRATION PROJECT PREPARED FOR Shaanxi Provincial Government And the Asian Development Bank ANZDEC LIMITED September 2007 CURRENCY EQUIVALENTS (as at 1 June 2007) Currency Unit – Chinese Yuan {CNY}1.00 = US $0.1308 $1.00 = CNY 7.64 ABBREVIATIONS ADB – Asian Development Bank BAP – Biodiversity Action Plan (of the PRC Government) CAS – Chinese Academy of Sciences CASS – Chinese Academy of Social Sciences CBD – Convention on Biological Diversity CBRC – China Bank Regulatory Commission CDA - Conservation Demonstration Area CNY – Chinese Yuan CO – company CPF – country programming framework CTF – Conservation Trust Fund EA – Executing Agency EFCAs – Ecosystem Function Conservation Areas EIRR – economic internal rate of return EPB – Environmental Protection Bureau EU – European Union FIRR – financial internal rate of return FDI – Foreign Direct Investment FYP – Five-Year Plan FS – Feasibility -

The Diary of a Manchu Soldier in Seventeenth-Century China: “My

THE DIARY OF A MANCHU SOLDIER IN SEVENTEENTH-CENTURY CHINA The Manchu conquest of China inaugurated one of the most successful and long-living dynasties in Chinese history: the Qing (1644–1911). The wars fought by the Manchus to invade China and consolidate the power of the Qing imperial house spanned over many decades through most of the seventeenth century. This book provides the first Western translation of the diary of Dzengmeo, a young Manchu officer, and recounts the events of the War of the Three Feudatories (1673–1682), fought mostly in southwestern China and widely regarded as the most serious internal military challenge faced by the Manchus before the Taiping rebellion (1851–1864). The author’s participation in the campaign provides the close-up, emotional perspective on what it meant to be in combat, while also providing a rare window into the overall organization of the Qing army, and new data in key areas of military history such as combat, armament, logistics, rank relations, and military culture. The diary represents a fine and rare example of Manchu personal writing, and shows how critical the development of Manchu studies can be for our knowledge of China’s early modern history. Nicola Di Cosmo joined the Institute for Advanced Study, School of Historical Studies, in 2003 as the Luce Foundation Professor in East Asian Studies. He is the author of Ancient China and Its Enemies (Cambridge University Press, 2002) and his research interests are in Mongol and Manchu studies and Sino-Inner Asian relations. ROUTLEDGE STUDIES -

Trampled Earth

6 ( Trampled Earth For over half a century, from roughly 1620 to 1680, the southwest fron- tier was in turmoil, much like the rest of China, and despite Zhu Xie- yuan’s best-laid plans for Shuixi the Ming state was incapable of restor- ing political authority over Guizhou and Yunnan following the She-An Rebellion. Subprefecture, prefecture, and even several provincial offices remained unstaffed during the 1630s and 1640s, and with the demise of the Ming in 1644, so, too, went the notion of civilian rule. “The Ming civilian bureaucracy,” as Lynn Struve noted, “was eclipsed by military organizations which originally had developed outside Ming control.”1 As one might suspect, many of these military organizations harbored anti-Ming sentiments. Gao Yingxiang (d. 1636), the godfather of sev- eral of China’s most notorious anti-Ming rebels, was able to channel popular antipathy due to years of economic decline, bureaucratic inepti- tude, and bone-jarring famine toward establishing a sprawling base of anti-Ming resistance in North China. Gao’s uncanny ability to consis- tently outwit his Ming adversaries distinguished him from many of the other small, regional warlords roaming the North China countryside, and his “national” stature attracted both the capable and desperate who hoped to capitalize on Gao’s potential. Two of Gao’s most notable lieu- tenants were Li Zicheng (1605?–45) and Zhang Xianzhong (1605–47). As a postal courier in Shaanxi, Li had proven himself to be a skilled horseman, expert marksman, and leader of men by the time the great famine of 1628 engulfed Shaanxi and forced him to abandon his government job. -

Final Program of CCC2020

第三十九届中国控制会议 The 39th Chinese Control Conference 程序册 Final Program 主办单位 中国自动化学会控制理论专业委员会 中国自动化学会 中国系统工程学会 承办单位 东北大学 CCC2020 Sponsoring Organizations Technical Committee on Control Theory, Chinese Association of Automation Chinese Association of Automation Systems Engineering Society of China Northeastern University, China 2020 年 7 月 27-29 日,中国·沈阳 July 27-29, 2020, Shenyang, China Proceedings of CCC2020 IEEE Catalog Number: CFP2040A -USB ISBN: 978-988-15639-9-6 CCC2020 Copyright and Reprint Permission: This material is permitted for personal use. For any other copying, reprint, republication or redistribution permission, please contact TCCT Secretariat, No. 55 Zhongguancun East Road, Beijing 100190, P. R. China. All rights reserved. Copyright@2020 by TCCT. 目录 (Contents) 目录 (Contents) ................................................................................................................................................... i 欢迎辞 (Welcome Address) ................................................................................................................................1 组织机构 (Conference Committees) ...................................................................................................................4 重要信息 (Important Information) ....................................................................................................................11 口头报告与张贴报告要求 (Instruction for Oral and Poster Presentations) .....................................................12 大会报告 (Plenary Lectures).............................................................................................................................14