The Generalissimo

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Guangzhou-Hongkong Strike, 1925-1926

The Guangzhou-Hongkong Strike, 1925-1926 Hongkong Workers in an Anti-Imperialist Movement Robert JamesHorrocks Submitted in accordancewith the requirementsfor the degreeof PhD The University of Leeds Departmentof East Asian Studies October 1994 The candidateconfirms that the work submitted is his own and that appropriate credit has been given where referencehas been made to the work of others. 11 Abstract In this thesis, I study the Guangzhou-Hongkong strike of 1925-1926. My analysis differs from past studies' suggestions that the strike was a libertarian eruption of mass protest against British imperialism and the Hongkong Government, which, according to these studies, exploited and oppressed Chinese in Guangdong and Hongkong. I argue that a political party, the CCP, led, organised, and nurtured the strike. It centralised political power in its hands and tried to impose its revolutionary visions on those under its control. First, I describe how foreign trade enriched many people outside the state. I go on to describe how Chinese-run institutions governed Hongkong's increasingly settled non-elite Chinese population. I reject ideas that Hongkong's mixed-class unions exploited workers and suggest that revolutionaries failed to transform Hongkong society either before or during the strike. My thesis shows that the strike bureaucracy was an authoritarian power structure; the strike's unprecedented political demands reflected the CCP's revolutionary political platform, which was sometimes incompatible with the interests of Hongkong's unions. I suggestthat the revolutionary elite's goals were not identical to those of the unions it claimed to represent: Hongkong unions preserved their autonomy in the face of revolutionaries' attempts to control Hongkong workers. -

© 2013 Yi-Ling Lin

© 2013 Yi-ling Lin CULTURAL ENGAGEMENT IN MISSIONARY CHINA: AMERICAN MISSIONARY NOVELS 1880-1930 BY YI-LING LIN DISSERTATION Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Comparative Literature in the Graduate College of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, 2013 Urbana, Illinois Doctoral committee: Professor Waïl S. Hassan, Chair Professor Emeritus Leon Chai, Director of Research Professor Emeritus Michael Palencia-Roth Associate Professor Robert Tierney Associate Professor Gar y G. Xu Associate Professor Rania Huntington, University of Wisconsin at Madison Abstract From a comparative standpoint, the American Protestant missionary enterprise in China was built on a paradox in cross-cultural encounters. In order to convert the Chinese—whose religion they rejected—American missionaries adopted strategies of assimilation (e.g. learning Chinese and associating with the Chinese) to facilitate their work. My dissertation explores how American Protestant missionaries negotiated the rejection-assimilation paradox involved in their missionary work and forged a cultural identification with China in their English novels set in China between the late Qing and 1930. I argue that the missionaries’ novelistic expression of that identification was influenced by many factors: their targeted audience, their motives, their work, and their perceptions of the missionary enterprise, cultural difference, and their own missionary identity. Hence, missionary novels may not necessarily be about conversion, the missionaries’ primary objective but one that suggests their resistance to Chinese culture, or at least its religion. Instead, the missionary novels I study culminate in a non-conversion theme that problematizes the possibility of cultural assimilation and identification over ineradicable racial and cultural differences. -

Echoes of Memory Volume 9

Echoes of Memory Volume 9 CONTENTS JACQUELINE MENDELS BIRN MICHEL MARGOSIS The Violins of Hope ...................................................2 In Transit, Spain ........................................................ 28 RUTH COHEN HARRY MARKOWICZ Life Is Good ....................................................................3 A Letter to the Late Mademoiselle Jeanne ..... 34 Sunday Lunch at Charlotte’s House ................... 36 GIDEON FRIEDER True Faith........................................................................5 ALFRED MÜNZER Days of Remembrance in Rymanow ..................40 ALBERT GARIH Reunion in Ebensee ................................................. 43 Flory ..................................................................................8 My Mother ..................................................................... 9 HALINA YASHAROFF PEABODY Lying ..............................................................................46 PETER GOROG A Gravestone for Those Who Have None .........12 ALFRED TRAUM A Three-Year-Old Saves His Mother ..................14 The S.S. Zion ...............................................................49 The Death Certificate That Saved Vienna, Chanukah 1938 ...........................................52 Our Lives ..................................................................................... 16 SUSAN WARSINGER JULIE KEEFER Bringing the Lessons Home ................................. 54 Did He Know I Was Jewish? ...................................18 Feeling Good ...............................................................55 -

CHP-121 Terms

T E R M S R E F E R E N C E D I N E P I S O D E The Chinese Civil War (Part 3) Ep. 121 P I N Y I N / T E R M C H I N E S E E N G L I S H / M E A N I N G Anhui 安徽 Province in China Chang Jiang 长江 The Yangzi River Changchun 长春 Capital of Jilin province in Manchuria Chen Cheng 陈诚 NRA General Chen Cheng 陈诚 NRA General Chen Mingren 陈明仁 NRA General Chen Yi 陈毅 PLA General and future foreign minister Chen Yun 陈云 One of Mao’s earliest political allies Dabie Mountains 大别山 Mountain chain just northeast of Wuhan in Hubei province Du Yuming 杜聿明 Nationalist General Fenghua 奉化 City and county in Zhejiang, near Ningbo Fu Zuoyi 傅作义 Nationalist General Fujian 福建 Province in China Gao Gang 高岗 PLA leader who served closely with Lin Biao Geng Biao 耿彪 PLA leader Guangdong 广东 Province in China Guangxi 广西 Province in China Han Gaozu 汉高祖 Liu Bang, founder of the Han Dynasty Hu Zongnan 胡宗南 Nationalist General Huabei 华北 Northern China Huaihai 淮海 Civil War Campaign in 1948 Huang Wei 黄伟 Nationalist General Hubei 湖北 Province in China Jiangsu 江苏 Province in China another military region of the Communists covering parts of Shanxi, Inner Jin-Cha-Ji 晋察冀 Mongolia and Hebei Jinzhou 锦州 City in Liaoning province Ming Dynasty loyalist who fought on against the Qing from his Taiwan base. Koxinga 郑成功 Also known as Cheng Ch’eng-kung Li Fuchun 李富春 PLA General Li Zongren 李宗仁 Nationalist General Liaoning 辽宁 Province in Manchuria Liaoshen 辽沈 Civil War Campaign in 1948 Lin Biao 林彪 PLA General in Manchuria and northern China Liu Bocheng 刘伯承 PLA General (Deng Xiaoping partner in civil -

Supplementary Material (ESI) for Environmental Science: Processes & Impacts This Journal Is © the Royal Society of Chemistry 2013

Electronic Supplementary Material (ESI) for Environmental Science: Processes & Impacts This journal is © The Royal Society of Chemistry 2013 Supplementary Material MANUSCRIPT TITLE: PAHs in Chinese environment: levels, inventory mass, source and toxic potency assessment AUTHORS: Ji-Zhong Wang, Cheng-Zhu Zhu, Tian-Hu Chen Affiliation: School of Resources and Environmental Engineering, Hefei University of Technology, Hefei 230009, China JOURNAL: Journal of Environmental Monitoring NO. OF PAGES: 43 NO. OF TABLES: 4 NO. FIGURES: 1 Electronic Supplementary Material (ESI) for Environmental Science: Processes & Impacts This journal is © The Royal Society of Chemistry 2013 Table S1. Basic information of natural source and economic and social development (all of these data were obtained from a database called Scientific Database of Chinese Academy of Sciences 1). Land area Watershed Glacier/desert Urban area Rural area Transportation Total water resources (km2) area (km2) area (km2) (km2) (km2)a area (km2)b volume (× 108 m3) Northern China Beijing 1.6E+04 1.1E+02 0.0E+00 5.5E+03 9.9E+03 3.6E+02 4.1E+01 Tianjing 1.2E+04 3.0E+02 0.0E+00 4.3E+03 7.0E+03 3.3E+02 1.5E+01 Hebei 1.9E+05 6.3E+02 1.1E+03 5.8E+03 1.8E+05 3.1E+03 2.4E+02 Shanxi 1.6E+05 5.6E+02 1.6E+03 8.8E+03 1.4E+05 1.6E+03 1.4E+02 Inner Mongolia 1.2E+06 4.0E+03 2.5E+05 1.3E+04 9.1E+05 3.2E+03 5.1E+02 Total 1.5E+06 5.6E+03 2.5E+05 3.8E+04 1.2E+06 8.6E+03 9.4E+02 Northeastern China Liaoning 1.6E+05 1.5E+03 0.0E+00 1.5E+04 1.5E+05 2.2E+03 3.6E+02 Jilin 1.8E+05 1.2E+03 4.0E+01 5.9E+04 1.2E+05 -

Bossypants? One, Because the Name Two and a Half Men Was Already Taken

Acknowledgments I would like to gratefully thank: Kay Cannon, Richard Dean, Eric Gurian, John Riggi, and Tracy Wigfield for their eyes and ears. Dave Miner for making me do this. Reagan Arthur for teaching me how to do this. Katie Miervaldis for her dedicated service and Latvian demeanor. Tom Ceraulo for his mad computer skills. Michael Donaghy for two years of Sundays. Jeff and Alice Richmond for their constant loving encouragement and their constant loving interruption, respectively. Thank you to Lorne Michaels, Marc Graboff, and NBC for allowing us to reprint material. Contents Front Cover Image Welcome Dedication Introduction Origin Story Growing Up and Liking It All Girls Must Be Everything Delaware County Summer Showtime! That’s Don Fey Climbing Old Rag Mountain Young Men’s Christian Association The Windy City, Full of Meat My Honeymoon, or A Supposedly Fun Thing I’ll Never Do Again Either The Secrets of Mommy’s Beauty Remembrances of Being Very Very Skinny Remembrances of Being a Little Bit Fat A Childhood Dream, Realized Peeing in Jars with Boys I Don’t Care If You Like It Amazing, Gorgeous, Not Like That Dear Internet 30 Rock: An Experiment to Confuse Your Grandparents Sarah, Oprah, and Captain Hook, or How to Succeed by Sort of Looking Like Someone There’s a Drunk Midget in My House A Celebrity’s Guide to Celebrating the Birth of Jesus Juggle This The Mother’s Prayer for Its Daughter What Turning Forty Means to Me What Should I Do with My Last Five Minutes? Acknowledgments Copyright * Or it would be the biggest understatement since Warren Buffett said, “I can pay for dinner tonight.” Or it would be the biggest understatement since Charlie Sheen said, “I’m gonna have fun this weekend.” So, you have options. -

C:\Documents and Settings\Fre...N.Default\Cache\0\11

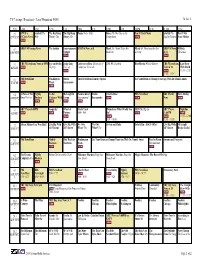

TV Listings Broadcast - Local Broadcast 94501 Fri, Jun. 8 PDT 6 PM 6:30 7 PM 7:30 8 PM 8:30 9 PM 9:30 10 PM 10:30 11 PM 11:30 2.1 KTVU 6 Seinfeld The The Big Bang The Big Bang House Better Half Bones The Hot Dog in the Ten O'Clock News Seinfeld The How I Met KTVUDT O'Clock News Wife Theory The Theory The Competition new English Patient Your Mother new 4.1 KRON 4 Evening News The Insider Entertainment KRON 4 News at 8 Monk Mr. Monk Takes His Monk Mr. Monk and the Red KRON 4 News 30 Rock KRONDT Tonight Medicine Herring at 11 Christmas new new 5.1 CBS 5 Eyewitness News at 6PM Eye on the Bay Judge Judy Undercover Boss University of CSI: NY Crushed Blue Bloods Whistle Blower CBS 5 Eyewitness Late Show KPIXDT new Daytrip: Tires of California, Riverside News at 11 With David new new 11:35 - 12:37 11:00 - 11:35 6.1 PBS NewsHour Washington Studio The Ed Sullivan Comedy Special Use Your Brain to Change Your Age With Dr. Daniel Amen KVIEDT new Week Sacramento new 6.2 A Place of Our Nightly To the McLaughlin Need to Know Studio Charlie Rose PBS NewsHour BBC World Tavis Smiley KVIEDT2 Own Week in Business Contrary With Group International Sacramento new new News new new new new new 7.1 ABC7 News 6:00PM Jeopardy! Wheel of Shark Tank Primetime: What Would You 20/20 The Big Lie ABC7 News Nightline KGODT new new Fortune 8:00 - 9:01 Do? new 11:00PM new new new new 11:35 - 12:00 9:01 - 10:00 11:00 - 11:35 7.2 Alyssa Milano Uses Wen Hair! Live Big With Live Big With We Owe We Owe Steven and Chris Total Gym - $14.95 Offer! Live Big With My Family KGODT2 Ali Vincent Ali Vincent What? The What? The Ali Vincent Recipe Rocks! 9.1 PBS NewsHour Nightly This Week in Washington Use Your Brain to Change Your Age With Dr. -

Language Loss Phenomenon in Taiwan: a Narrative Inquiry—Autobiography and Phenomenological Study

Language Loss Phenomenon in Taiwan: A Narrative Inquiry—Autobiography and Phenomenological Study By Wan-Hua Lai A Thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies of The University of Manitoba in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of MASTER OF EDUCATION Department of Curriculum, Teaching, and Learning University of Manitoba, Faculty of Education Winnipeg Copyright © 2012 by Wan-Hua Lai ii Table of Content Table of Content…………………………………………………………………………………………………..……ii List of Tables…………………………………………………………………………………………………..……...viii List of Figures……………………………………………………………………………………………………………ix Abstract…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………...xi Acknowledgement………………………………………………………………………………………………..…xii Dedication………………………………………………………………………………………………………………xiv Chapter One: Introduction…………………………………………………………………………………….….1 Mandarin Research Project……………………………………………………………………………………2 Confusion about My Mother Tongue……………………………………………………….……………2 From Mandarin to Taigi………………………………………………………………………………………..3 Taiwan, a Colonial Land………………………………………………………………………………………..3 Study on the Language Loss in Taiwan………………………………………………………………….4 Archival Research………………………………………………………………………………………………….4 Chapter Two: My Discovery- A Different History of Taiwan……………………………………….6 Geography…………………………………………………………………………………………………………….7 Population……………………………………………….…………………………………………………….……9 Culture…………………………………………………………………………………………..……………………..9 Society………………………………………………………………………………..………………………………10 Education…………………………………………………………………………………………………….………11 Economy……………………………………………………………………………………….…………….………11 -

Also by Jung Chang

Also by Jung Chang Empress Dowager Cixi: The Concubine Who Launched Modern China Mao: The Unknown Story (with Jon Halliday) Wild Swans: Three Daughters of China THIS IS A BORZOI BOOK PUBLISHED BY ALFRED A. KNOPF Copyright © 2019 by Globalflair Ltd. All rights reserved. Published in the United States by Alfred A. Knopf, a division of Penguin Random House LLC, New York. Originally published in hardcover in Great Britain by Jonathan Cape, an imprint of Vintage, a division of Penguin Random House Ltd., London, in 2019. www.aaknopf.com Knopf, Borzoi Books, and the colophon are registered trademarks of Penguin Random House LLC. Library of Congress Control Number: 2019943880 ISBN 9780451493507 (hardcover) ISBN 9780451493514 (ebook) ISBN 9780525657828 (open market) Ebook ISBN 9780451493514 Cover images: (The Soong sisters) Historic Collection / Alamy; (fabric) Chakkrit Wannapong / Alamy Cover design by Chip Kidd v5.4 a To my mother Contents Cover Also by Jung Chang Title Page Copyright Dedication List of Illustrations Map of China Introduction Part I: The Road to the Republic (1866–1911) 1 The Rise of the Father of China 2 Soong Charlie: A Methodist Preacher and a Secret Revolutionary Part II: The Sisters and Sun Yat-sen (1912–1925) 3 Ei-ling: A ‘Mighty Smart’ Young Lady 4 China Embarks on Democracy 5 The Marriages of Ei-ling and Ching-ling 6 To Become Mme Sun 7 ‘I wish to follow the example of my friend Lenin’ Part III: The Sisters and Chiang Kai-shek (1926–1936) 8 Shanghai Ladies 9 May-ling Meets the Generalissimo 10 Married to a Beleaguered -

The History and Politics of Taiwan's February 28

The History and Politics of Taiwan’s February 28 Incident, 1947- 2008 by Yen-Kuang Kuo BA, National Taiwan Univeristy, Taiwan, 1991 BA, University of Victoria, 2007 MA, University of Victoria, 2009 A Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in the Department of History © Yen-Kuang Kuo, 2020 University of Victoria All rights reserved. This dissertation may not be reproduced in whole or in part, by photocopy or other means, without the permission of the author. ii Supervisory Committee The History and Politics of Taiwan’s February 28 Incident, 1947- 2008 by Yen-Kuang Kuo BA, National Taiwan Univeristy, Taiwan, 1991 BA, University of Victoria, 2007 MA, University of Victoria, 2009 Supervisory Committee Dr. Zhongping Chen, Supervisor Department of History Dr. Gregory Blue, Departmental Member Department of History Dr. John Price, Departmental Member Department of History Dr. Andrew Marton, Outside Member Department of Pacific and Asian Studies iii Abstract Taiwan’s February 28 Incident happened in 1947 as a set of popular protests against the postwar policies of the Nationalist Party, and it then sparked militant actions and political struggles of Taiwanese but ended with military suppression and political persecution by the Nanjing government. The Nationalist Party first defined the Incident as a rebellion by pro-Japanese forces and communist saboteurs. As the enemy of the Nationalist Party in China’s Civil War (1946-1949), the Chinese Communist Party initially interpreted the Incident as a Taiwanese fight for political autonomy in the party’s wartime propaganda, and then reinterpreted the event as an anti-Nationalist uprising under its own leadership. -

Scoring One for the Other Team

FIVE TURTLES IN A FLASK: FOR TAIWAN’S OUTER ISLANDS, AN UNCERTAIN FUTURE HOLDS A CERTAIN FATE A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE DIVISION OF THE UNIVERSITY OF HAWAI‘I AT MĀNOA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS IN ASIAN STUDIES MAY 2018 By Edward W. Green, Jr. Thesis Committee: Eric Harwit, Chairperson Shana J. Brown Cathryn H. Clayton Keywords: Taiwan independence, offshore islands, strait crisis, military intervention TABLE OF CONTENTS Page List of Tables ................................................................................................................ ii List of Figures ............................................................................................................... iii I. Introduction ............................................................................................................... 1 II. Scope and Organization ........................................................................................... 6 III. Dramatis Personae: The Five Islands ...................................................................... 9 III.1. Itu Aba ..................................................................................................... 11 III.2. Matsu ........................................................................................................ 14 III.3. The Pescadores ......................................................................................... 16 III.4. Pratas ....................................................................................................... -

The Darkest Red Corner Matthew James Brazil

The Darkest Red Corner Chinese Communist Intelligence and Its Place in the Party, 1926-1945 Matthew James Brazil A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for a Doctor of Philosophy Department of Government and International Relations Business School University of Sydney 17 December 2012 Statement of Originality This is to certify that to the best of my knowledge, the content of this thesis is my own work. This thesis has not been submitted previously, either in its entirety or substantially, for a higher degree or qualifications at any other university or institute of higher learning. I certify that the intellectual content of this thesis is the product of my own work and that all the assistance received in preparing this thesis and sources has been acknowledged. Matthew James Brazil i ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Before and during this project I met a number of people who, directly or otherwise, encouraged my belief that Chinese Communist intelligence was not too difficult a subject for academic study. Michael Dutton and Scot Tanner provided invaluable direction at the very beginning. James Mulvenon requires special thanks for regular encouragement over the years and generosity with his time, guidance, and library. Richard Corsa, Monte Bullard, Tom Andrukonis, Robert W. Rice, Bill Weinstein, Roderick MacFarquhar, the late Frank Holober, Dave Small, Moray Taylor Smith, David Shambaugh, Steven Wadley, Roger Faligot, Jean Hung and the staff at the Universities Service Centre in Hong Kong, and the kind personnel at the KMT Archives in Taipei are the others who can be named. Three former US diplomats cannot, though their generosity helped my understanding of links between modern PRC intelligence operations and those before 1949.