Echoes of Memory Volume 9

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Buddhism and Responses to Disability, Mental Disorders and Deafness in Asia

Buddhism and Responses to Disability, Mental Disorders and Deafness in Asia. A bibliography of historical and modern texts with introduction and partial annotation, and some echoes in Western countries. [This annotated bibliography of 220 items suggests the range and major themes of how Buddhism and people influenced by Buddhism have responded to disability in Asia through two millennia, with cultural background. Titles of the materials may be skimmed through in an hour, or the titles and annotations read in a day. The works listed might take half a year to find and read.] M. Miles (compiler and annotator) West Midlands, UK. November 2013 Available at: http://www.independentliving.org/miles2014a and http://cirrie.buffalo.edu/bibliography/buddhism/index.php Some terms used in this bibliography Buddhist terms and people. Buddhism, Bouddhisme, Buddhismus, suffering, compassion, caring response, loving kindness, dharma, dukkha, evil, heaven, hell, ignorance, impermanence, kamma, karma, karuna, metta, noble truths, eightfold path, rebirth, reincarnation, soul, spirit, spirituality, transcendent, self, attachment, clinging, delusion, grasping, buddha, bodhisatta, nirvana; bhikkhu, bhikksu, bhikkhuni, samgha, sangha, monastery, refuge, sutra, sutta, bonze, friar, biwa hoshi, priest, monk, nun, alms, begging; healing, therapy, mindfulness, meditation, Gautama, Gotama, Maitreya, Shakyamuni, Siddhartha, Tathagata, Amida, Amita, Amitabha, Atisha, Avalokiteshvara, Guanyin, Kannon, Kuan-yin, Kukai, Samantabhadra, Santideva, Asoka, Bhaddiya, Khujjuttara, -

THE POLISH POLICE Collaboration in the Holocaust

THE POLISH POLICE Collaboration in the Holocaust Jan Grabowski The Polish Police Collaboration in the Holocaust Jan Grabowski INA LEVINE ANNUAL LECTURE NOVEMBER 17, 2016 The assertions, opinions, and conclusions in this occasional paper are those of the author. They do not necessarily reflect those of the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. First printing, April 2017 Copyright © 2017 by Jan Grabowski THE INA LEVINE ANNUAL LECTURE, endowed by the William S. and Ina Levine Foundation of Phoenix, Arizona, enables the Center to bring a distinguished scholar to the Museum each year to conduct innovative research on the Holocaust and to disseminate this work to the American public. Wrong Memory Codes? The Polish “Blue” Police and Collaboration in the Holocaust In 2016, seventy-one years after the end of World War II, the Polish Ministry of Foreign Affairs disseminated a long list of “wrong memory codes” (błędne kody pamięci), or expressions that “falsify the role of Poland during World War II” and that are to be reported to the nearest Polish diplomat for further action. Sadly—and not by chance—the list elaborated by the enterprising humanists at the Polish Foreign Ministry includes for the most part expressions linked to the Holocaust. On the long list of these “wrong memory codes,” which they aspire to expunge from historical narrative, one finds, among others: “Polish genocide,” “Polish war crimes,” “Polish mass murders,” “Polish internment camps,” “Polish work camps,” and—most important for the purposes of this text—“Polish participation in the Holocaust.” The issue of “wrong memory codes” will from time to time reappear in this study. -

2012 Morpheus Staff

2012 Morpheus Staff Editor-in-Chief Laura Van Valkenburgh Contest Director Lexie Pinkelman Layout & Design Director Brittany Cook Marketing Director Brittany Cook Cover Design Lemming Productions Merry the Wonder Cat appears courtesy of Sandy’s House-o-Cats. No animals were injured in the creation of this publication. Heidelberg University Morpheus Literary Magazine 2012 2 Heidelberg University Morpheus Literary Magazine 2012 3 Table of Contents Morpheus Literary Competition Author Biographies...................5 3rd Place Winners.....................10 2nd Place Winners....................26 1st place Winners.....................43 Senior Writing Projects Author Biographies...................68 Brittany Cook...........................70 Lexie Pinkelman.......................109 Laura Van Valkenburgh...........140 Heidelberg University Morpheus Literary Magazine 2012 4 Author Biographies Logan Burd Logan Burd is a junior English major from Tiffin, Ohio just trying to take advantage of any writing opportunity Heidelberg will allow. For “Onan on Hearing of his Broth- er’s Smiting,” Logan would like to thank Dr. Bill Reyer for helping in the revision process and Onan for making such a fas- cinating biblical tale. Erin Crenshaw Erin Crenshaw is a senior at Heidelberg. She is an English literature major. She writes. She dances. She prances. She leaps. She weeps. She sighs. She someday dies. Enjoy the Morpheus! Heidelberg University Morpheus Literary Magazine 2012 5 April Davidson April Davidson is a senior German major and English Writing minor from Cincin- nati, Ohio. She is the president of both the German Club and Brown/France Hall Council. She is also a member of Berg Events Council. After April graduates, she will be entering into a Masters program for German Studies. -

American Intelligence and the Question of Hitler's Death

American Intelligence and the Question of Hitler’s Death Undergraduate Research Thesis Presented in partial fulfillment of the requirements for graduation with honors research distinction in History in the Undergraduate colleges of The Ohio State University by Kelsey Mullen The Ohio State University November 2014 Project Advisor: Professor Alice Conklin, Department of History Project Mentor: Doctoral Candidate Sarah K. Douglas, Department of History American Intelligence and the Question of Hitler’s Death 2 Introduction The fall of Berlin marked the end of the European theatre of the Second World War. The Red Army ravaged the city and laid much of it to waste in the early days of May 1945. A large portion of Hitler’s inner circle, including the Führer himself, had been holed up in the Führerbunker underneath the old Reich Chancellery garden since January of 1945. Many top Nazi Party officials fled or attempted to flee the city ruins in the final moments before their destruction at the Russians’ hands. When the dust settled, the German army’s capitulation was complete. There were many unanswered questions for the Allies of World War II following the Nazi surrender. Invading Russian troops, despite recovering Hitler’s body, failed to disclose this fact to their Allies when the battle ended. In September of 1945, Dick White, the head of counter intelligence in the British zone of occupation, assigned a young scholar named Hugh Trevor- Roper to conduct an investigation into Hitler’s last days in order to refute the idea the Russians promoted and perpetuated that the Führer had escaped.1 Major Trevor-Roper began his investigation on September 18, 1945 and presented his conclusions to the international press on November 1, 1945. -

MUSIC NOTES: Exploring Music Listening Data As a Visual Representation of Self

MUSIC NOTES: Exploring Music Listening Data as a Visual Representation of Self Chad Philip Hall A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of: Master of Design University of Washington 2016 Committee: Kristine Matthews Karen Cheng Linda Norlen Program Authorized to Offer Degree: Art ©Copyright 2016 Chad Philip Hall University of Washington Abstract MUSIC NOTES: Exploring Music Listening Data as a Visual Representation of Self Chad Philip Hall Co-Chairs of the Supervisory Committee: Kristine Matthews, Associate Professor + Chair Division of Design, Visual Communication Design School of Art + Art History + Design Karen Cheng, Professor Division of Design, Visual Communication Design School of Art + Art History + Design Shelves of vinyl records and cassette tapes spark thoughts and mem ories at a quick glance. In the shift to digital formats, we lost physical artifacts but gained data as a rich, but often hidden artifact of our music listening. This project tracked and visualized the music listening habits of eight people over 30 days to explore how this data can serve as a visual representation of self and present new opportunities for reflection. 1 exploring music listening data as MUSIC NOTES a visual representation of self CHAD PHILIP HALL 2 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF: master of design university of washington 2016 COMMITTEE: kristine matthews karen cheng linda norlen PROGRAM AUTHORIZED TO OFFER DEGREE: school of art + art history + design, division -

Bossypants? One, Because the Name Two and a Half Men Was Already Taken

Acknowledgments I would like to gratefully thank: Kay Cannon, Richard Dean, Eric Gurian, John Riggi, and Tracy Wigfield for their eyes and ears. Dave Miner for making me do this. Reagan Arthur for teaching me how to do this. Katie Miervaldis for her dedicated service and Latvian demeanor. Tom Ceraulo for his mad computer skills. Michael Donaghy for two years of Sundays. Jeff and Alice Richmond for their constant loving encouragement and their constant loving interruption, respectively. Thank you to Lorne Michaels, Marc Graboff, and NBC for allowing us to reprint material. Contents Front Cover Image Welcome Dedication Introduction Origin Story Growing Up and Liking It All Girls Must Be Everything Delaware County Summer Showtime! That’s Don Fey Climbing Old Rag Mountain Young Men’s Christian Association The Windy City, Full of Meat My Honeymoon, or A Supposedly Fun Thing I’ll Never Do Again Either The Secrets of Mommy’s Beauty Remembrances of Being Very Very Skinny Remembrances of Being a Little Bit Fat A Childhood Dream, Realized Peeing in Jars with Boys I Don’t Care If You Like It Amazing, Gorgeous, Not Like That Dear Internet 30 Rock: An Experiment to Confuse Your Grandparents Sarah, Oprah, and Captain Hook, or How to Succeed by Sort of Looking Like Someone There’s a Drunk Midget in My House A Celebrity’s Guide to Celebrating the Birth of Jesus Juggle This The Mother’s Prayer for Its Daughter What Turning Forty Means to Me What Should I Do with My Last Five Minutes? Acknowledgments Copyright * Or it would be the biggest understatement since Warren Buffett said, “I can pay for dinner tonight.” Or it would be the biggest understatement since Charlie Sheen said, “I’m gonna have fun this weekend.” So, you have options. -

C:\Documents and Settings\Fre...N.Default\Cache\0\11

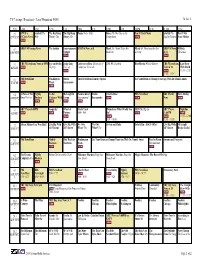

TV Listings Broadcast - Local Broadcast 94501 Fri, Jun. 8 PDT 6 PM 6:30 7 PM 7:30 8 PM 8:30 9 PM 9:30 10 PM 10:30 11 PM 11:30 2.1 KTVU 6 Seinfeld The The Big Bang The Big Bang House Better Half Bones The Hot Dog in the Ten O'Clock News Seinfeld The How I Met KTVUDT O'Clock News Wife Theory The Theory The Competition new English Patient Your Mother new 4.1 KRON 4 Evening News The Insider Entertainment KRON 4 News at 8 Monk Mr. Monk Takes His Monk Mr. Monk and the Red KRON 4 News 30 Rock KRONDT Tonight Medicine Herring at 11 Christmas new new 5.1 CBS 5 Eyewitness News at 6PM Eye on the Bay Judge Judy Undercover Boss University of CSI: NY Crushed Blue Bloods Whistle Blower CBS 5 Eyewitness Late Show KPIXDT new Daytrip: Tires of California, Riverside News at 11 With David new new 11:35 - 12:37 11:00 - 11:35 6.1 PBS NewsHour Washington Studio The Ed Sullivan Comedy Special Use Your Brain to Change Your Age With Dr. Daniel Amen KVIEDT new Week Sacramento new 6.2 A Place of Our Nightly To the McLaughlin Need to Know Studio Charlie Rose PBS NewsHour BBC World Tavis Smiley KVIEDT2 Own Week in Business Contrary With Group International Sacramento new new News new new new new new 7.1 ABC7 News 6:00PM Jeopardy! Wheel of Shark Tank Primetime: What Would You 20/20 The Big Lie ABC7 News Nightline KGODT new new Fortune 8:00 - 9:01 Do? new 11:00PM new new new new 11:35 - 12:00 9:01 - 10:00 11:00 - 11:35 7.2 Alyssa Milano Uses Wen Hair! Live Big With Live Big With We Owe We Owe Steven and Chris Total Gym - $14.95 Offer! Live Big With My Family KGODT2 Ali Vincent Ali Vincent What? The What? The Ali Vincent Recipe Rocks! 9.1 PBS NewsHour Nightly This Week in Washington Use Your Brain to Change Your Age With Dr. -

1 X 56 Or 1 X 74

1 x 56 or 1 x 74 In this fascinating documentary, historian Bettany Hughes travels to the seven wonders of the Buddhist world and offers a unique insight into one of the most ancient belief systems still practiced today. Buddhism began 2,500 years ago when one man had an amazing inter- nal revelation underneath a peepul tree in India. Today it is practiced by over 350 million people worldwide, with numbers continuing to grow year after year. In an attempt to gain a better understanding of the different beliefs and 1 x 56 or 1 x 74 practices that form the core of the Buddhist philosophy, and investigate how Buddhism started and where it travelled to, Hughes visits some of the most CONTACT spectacular monuments built by Buddhists across the globe. Tom Koch, Vice President PBS International Her journey begins at the Mahabodhi Temple in India, where Buddhism 10 Guest Street was born; here Hughes examines the foundations of the belief system—the Boston, MA 02135 USA three jewels. TEL: +1-617-208-0735 At Nepal’s Boudhanath Stupa, she looks deeper into the concept of FAX: +1-617-208-0783 dharma—the teaching of Buddha, and at the Temple of the Tooth in Sri [email protected] pbsinternational.org Lanka, Bettany explores karma, the idea that our intentional acts will be mir- rored in the future. At Wat Pho Temple in Thailand, Hughes explores samsara, the endless cycle of birth and death that Buddhists seek to end by achieving enlighten- ment, before travelling to Angkor Wat in Cambodia to learn more about the practice of meditation. -

UNDERSTANDING PORTRAYALS of LAW ENFORCEMENT OFFICERS in HIP-HOP LYRICS SINCE 2009 By

ON THE BEAT: UNDERSTANDING PORTRAYALS OF LAW ENFORCEMENT OFFICERS IN HIP-HOP LYRICS SINCE 2009 by Francesca A. Keesee A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of George Mason University in Partial Fulfillment of The Requirements for the Degrees of Master of Science Conflict Analysis and Resolution Master of Arts Conflict Resolution and Mediterranean Security Committee: ___________________________________________ Chair of Committee ___________________________________________ ___________________________________________ ___________________________________________ Graduate Program Director ___________________________________________ Dean, School for Conflict Analysis and Resolution Date: _____________________________________ Fall Semester 2017 George Mason University Fairfax, VA University of Malta Valletta, Malta On the Beat: Understanding Portrayals of Law Enforcement Officers in Hip-hop Lyrics Since 2009 A Thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degrees of Master of Science at George Mason University and Master of Arts at the University of Malta by Francesca A. Keesee Bachelor of Arts University of Virginia, 2015 Director: Juliette Shedd, Professor School for Conflict Analysis and Resolution Fall Semester 2017 George Mason University Fairfax, Virginia University of Malta Valletta, Malta Copyright 2016 Francesca A. Keesee All Rights Reserved ii DEDICATION This is dedicated to all victims of police brutality. iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I am forever grateful to my best friend, partner in crime, and husband, Patrick. -

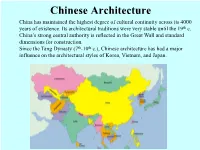

Chinese Architecture China Has Maintained the Highest Degree of Cultural Continuity Across Its 4000 Years of Existence

Chinese Architecture China has maintained the highest degree of cultural continuity across its 4000 years of existence. Its architectural traditions were very stable until the 19th c. China’s strong central authority is reflected in the Great Wall and standard dimensions for construction. Since the Tang Dynasty (7th-10th c.), Chinese architecture has had a major influence on the architectural styles of Korea, Vietnam, and Japan. Neolithic Houses at Banpo, ca 2000 BCE These dwellings used readily available materials—wood, thatch, and earth— to provide shelter. A central hearth is also part of many houses. The rectangular houses were sunk a half story into the ground. The Great Wall of China, 221 BCE-1368 CE. 19-39’ in height and 16’ wide. Almost 4000 miles long. Begun in pieces by feudal lords, unified by the first Qin emperor and largely rebuilt and extended during the Ming Dynasty (1368-1644 CE) Originally the great wall was made with rammed earth but during the Ming Dynasty its height was raised and it was cased with bricks or stones. https://youtu.be/o9rSlYxJIIE 1;05 Deified Lao Tzu. 8th - 11th c. Taoism or Daoism is a Chinese mystical philosophy traditionally founded by Lao-tzu in the sixth century BCE. It seeks harmony of human action and the world through study of nature. It tends to emphasize effortless Garden of the Master of the action, "naturalness", simplicity Fishing Nets in Suzhou, 1140. and spontaneity. Renovated in 1785 Life is a series of natural and spontaneous changes. Don’t resist them – that only creates sorrow. -

Fast Lane by Kristen Ashley

FAST LANE BY KRISTEN ASHLEY Acknowledgments Many moons ago, I had the occasion to really listen to the song “Life in the Fast Lane” by The Eagles. I’d heard it before, tons of times. But on that listen, something struck me. Being a romantic at heart, a romance novelist and addicted to romance for as long as I can remember, that song captured me as lyrics often do. Especially if a love story is told. Any kind of love story. Even the ones without happy endings. Maybe especially ones without happy endings. So much said in a few spare lines. So many emotions welling. And as is the magic of music, on each new listen, it happens again like you’d never heard that song before. I became obsessed with it, inspired by this cautionary tale, and determined to find the right story that would fit that inspiration. It was something I thought I’d fiddle with “someday,” which is where a great number of my ideas or inspirations are relegated. Then I read Taylor Jenkins Reid’s Daisy Jones and the Six. I have never, in my life, put down a book because I was loving it so much, I had to draw it out for as long as I could. And then, weeks later, I picked it up, only begrudgingly, because I knew opening that book again would mean finishing it, and I never wanted it to end. The fresh, unique way TJR told that story as an oral history of a 70s rock band blew my mind. -

The Brookings Institution Center for Northeast Asian Policy Studies

THE BROOKINGS INSTITUTION CENTER FOR NORTHEAST ASIAN POLICY STUDIES The 2004 Legislative Council Elections and Implications for U.S. Policy toward Hong Kong Wednesday, September 15, 2004 Introduction: RICHARD BUSH Director, Center for Northeast Asian Policy Studies The Brookings Institution Presenter: SONNY LO SHIU-HING Associate Professor of Political Science University of Waterloo Discussant: ELLEN BORK Deputy Director Project for the New American Century [TRANSCRIPT PREPARED FROM A TAPE RECORDING.] THE BROOKINGS INSTITUTION CENTER FOR NORTHEAST ASIAN POLICY STUDIES 1775 MASSACHUSETTS AVENUE, NW WASHINGTON, D.C. 20036 202-797-6307 P R O C E E D I N G S MR. BUSH: [In progress] I've long thought that politically Hong Kong plays a very important role in the Chinese political system because it can be, I think, a test bed, or a place to experiment on different political forums on how to run large Chinese cities in an open, competitive, and accountable way. So how Hong Kong's political development proceeds is very important for some larger and very significant issues for the Chinese political system as a whole, and therefore the debate over democratization in Hong Kong is one that has significance that reaches much beyond the rights and political participation of the people there. The election that occurred last Sunday is a kind of punctuation mark in that larger debate over democratization, and we're very pleased to have two very qualified people to talk to us today. The first is Professor Sonny Lo Shiu-hing, who has just joined the faculty of the University of Waterloo in Canada.