Cincinnati's Doolittle Raider at War

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Admiral William Frederick Halsey by Ruben Pang

personality profile 69 Admiral William Frederick Halsey by Ruben Pang IntRoductIon Early Years fleet admiral William halsey was born in elizabeth, frederick halsey (30 october new Jersey to a family of naval 1882 – 16 august 1959) was a tradition. his father was a captain united states navy (USN) officer in the USN. hasley naturally who served in both the first and followed in his footsteps, second World Wars (WWi and enrolling in the united states WWII). he was commander of (US) naval academy in 1900.3 the south pacific area during as a cadet, he held several the early years of the pacific extracurricular positions. he War against Japan and became played full-back for the football http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Halsey.JPG commander of the third fleet team, became president of the Fleet Admiral William Frederick Halsey for the remainder of the war, athletic association, and as during which he supported first classman “had his name general douglas macarthur’s engraved on the thompson advance on the philippines in trophy cup as the midshipman 1944. over the course of war, who had done most during halsey earned the reputation the year for the promotion of of being one of america’s most athletics.”4 aggressive fighting admirals, often driven by instinct over from 1907 to 1909, he gained intellect. however, his record substantial maritime experience also includes unnecessary losses while sailing with the “great at leyte gulf and damage to his White fleet” in a global third fleet during the typhoon circumnavigation.5 in 1909, of 1944 or “hasley’s typhoon,” halsey received instruction in the violent tempest that sank torpedoes with the reserve three destroyers and swept torpedo flotilla in charleston, away 146 naval aircraft. -

Echoes of Memory Volume 9

Echoes of Memory Volume 9 CONTENTS JACQUELINE MENDELS BIRN MICHEL MARGOSIS The Violins of Hope ...................................................2 In Transit, Spain ........................................................ 28 RUTH COHEN HARRY MARKOWICZ Life Is Good ....................................................................3 A Letter to the Late Mademoiselle Jeanne ..... 34 Sunday Lunch at Charlotte’s House ................... 36 GIDEON FRIEDER True Faith........................................................................5 ALFRED MÜNZER Days of Remembrance in Rymanow ..................40 ALBERT GARIH Reunion in Ebensee ................................................. 43 Flory ..................................................................................8 My Mother ..................................................................... 9 HALINA YASHAROFF PEABODY Lying ..............................................................................46 PETER GOROG A Gravestone for Those Who Have None .........12 ALFRED TRAUM A Three-Year-Old Saves His Mother ..................14 The S.S. Zion ...............................................................49 The Death Certificate That Saved Vienna, Chanukah 1938 ...........................................52 Our Lives ..................................................................................... 16 SUSAN WARSINGER JULIE KEEFER Bringing the Lessons Home ................................. 54 Did He Know I Was Jewish? ...................................18 Feeling Good ...............................................................55 -

H1 Toryjournal

TheWittenberg H1 toryJournal Wittenberg University • Springfield, Ohio Volume XXXII Spring2003 From the Editors: Greetings from the editors of the WittenbergUniversity History Journal. As you may notice, the format for this year's publication has changed from previous issues. We hope that this change is the first step in redefining the journal by making the physical publication even more professional. The within articles are, as always, excellent examples of what students here at Wittenberg are writing, and we hope that you wili enjoy reading them. A very special thanks is due to Tom and Tina Lagos, the Admission Office at Wittenberg and the Wittenberg History Club for their generous donations. Without their financial assistance, this publication would not have been possible. We would also like to thank all those involved in making this journal possible and congratulations to all the writers on creating such superior works. Mark Huber, Mandy Oleson and Dustin Plummer The Wittenberg University History Journal 2002-03 Editorial Staff '04, '03 Co-editors .......................... Mark Huber Mandy Oleson and Dustin Plummet '03 Editorial Staff ................. Erica Fornari '04, Greer Illingworth '05 Nicole Roberts '03 and Rebecca Roush '03 Advisor ......................................................... Dr. Jim Huffman The Hartje Papers The Martha and Robert G. Hartje Award is presented annually to a Senior in the spring semester. The History Department determines the five finalists who write a 600 to 800 word narrative essay dealing with a historical event or figure. The finalists must have at least a 2.7 grade point average and have completed at least six history courses. The winner is awarded $500 at a spring semester History Department colloquium and the winning paper is included in the HistoryJournal. -

The US Navy Japanese/Oriental Language School Archival Project

The US Navy Japanese/Oriental Language School Archival Project The Interpreter Archives, University of Colorado at Boulder Libraries Number 243 Remember September 11, 2001 [email protected] May 1, 2018 Our Mission stationed. All of that stopped not know what it did exactly. I draft. A Russian complimented when I landed at Cold Bay. The told him what it was, and he at me on using the correct and In the Spring of 2000, the best I could do was to draw a last recognized it. rather obscure word for “draft” Archives continued the origi- picture of snow on the envelope, in Russian. American Lifestyle nal efforts of Captain Roger to give my wife a hint that I was In addition to seeing movies Pineau and William Hudson, somewhere cold. Seeing life from the Russian side about America, the Russians had and the Archives first at- Because of my language was interesting. For example, heard about our lavish life style. tempts in 1992, to gather the skills, I had been assigned to Russian cooks liked how we had They wanted to know how many papers, letters, photographs, Project Hula, although it was so pictures of the food on the cars I owned. When I told them I and records of graduates of secret, the Navy never outside of the cans [some did not own a car; I had to the US Navy Japanese/ mentioned the name or what it imagination required]. In explain that I was only 20 years Oriental Language School, was about. Much later, I found America, many different old and a student before the war, University of Colorado at out the United States was companies sell the same kind of so I had not had a chance to buy Boulder, 1942-1946. -

Guide to the Doolittle Tokyo Raider Association Papers (1947

Guide to the Doolittle Tokyo Raider Association Papers (1947 - ) 26 linear feet Accession Number: 54-06 Collection Number: H54-06 Collection Dates: 1931 - Bulk Dates: 1942 - 2005 Prepared by Thomas J. Allen CITATION: The Doolittle Tokyo Raiders Association Papers, Box number, Folder number, History of Aviation Collection, Special Collections Department, McDermott Library, The University of Texas at Dallas. Special Collections Department McDermott Library, The University of Texas at Dallas Contents Historical Sketch ................................................................................................................. 3 Sources ................................................................................................................................ 3 Additional Sources .............................................................................................................. 3 Series Description ............................................................................................................... 4 Scope and Content Note...................................................................................................... 5 Collection Note ................................................................................................................... 8 Provenance Statement ......................................................................................................... 8 Literary Rights Statement ................................................................................................... 8 2 -

OH-323) 482 Pgs

Processed by: EWH LEE Date: 10-13-94 LEE, WILLIAM L. (OH-323) 482 pgs. OPEN Military associate of General Eisenhower; organizer of Philippine Air Force under Douglas MacArthur, 1935-38 Interview in 3 parts: Part I: 1-211; Part II: 212-368; Part III: 369-482 DESCRIPTION: [Interview is based on diary entries and is very informal. Mrs. Lee is present and makes occasional comments.] PART I: Identification of and comments about various figures and locations in film footage taken in the Philippines during the 1930's; flying training and equipment used at Camp Murphy; Jimmy Ord; building an airstrip; planes used for training; Lee's background (including early duty assignments; volunteering for assignment to the Philippines); organizing and developing the Philippine Air Unit of the constabulary (including Filipino officer assistants; Curtis Lambert; acquiring training aircraft); arrival of General Douglas MacArthur and staff (October 26, 1935); first meeting with Major Eisenhower (December 14, 1935); purpose of the constabulary; Lee's financial situation; building Camp Murphy (including problems; plans for the air unit; aircraft); Lee's interest in a squadron of airplanes for patrol of coastline vs. MacArthur's plan for seapatrol boats; Sid Huff; establishing the air unit (including determining the kind of airplanes needed; establishing physical standards for Filipino cadets; Jesus Villamor; standards of training; Lee's assessment of the success of Filipino student pilots); "Lefty" Parker, Lee, and Eisenhower's solo flight; early stages in formation -

The BG News October 1, 1993

Bowling Green State University ScholarWorks@BGSU BG News (Student Newspaper) University Publications 10-1-1993 The BG News October 1, 1993 Bowling Green State University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.bgsu.edu/bg-news Recommended Citation Bowling Green State University, "The BG News October 1, 1993" (1993). BG News (Student Newspaper). 5580. https://scholarworks.bgsu.edu/bg-news/5580 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 4.0 License. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the University Publications at ScholarWorks@BGSU. It has been accepted for inclusion in BG News (Student Newspaper) by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@BGSU. 4? The BG News Volume 76, Issue 27 Bowling Creen, Ohio Friday, October 1, 1993 Briefs Only two of six state goals met Weather by John Chalfant will demonstrate competency in all sections of ninth-grade profi- Rain this weekend: The Associated Press English, mathematics, science, ciency tests in reading, writing, "Where are we world class? D-plus. history and geography. mathematics and citizenship Friday, partly sunny The fact is that we, relatively Other goals: U.S. students will after two attempts. early. Increasing clouds COLUMBUS, Ohio - Gov. speaking, compared to other be first in the world in science during the afternoon with George Volnovich handed out an and mathematics achievement; The state for the first time is scattered showers develop- education report card Thursday nations in the world, are not getting every adult will be literate; every using results of surveys to ing. Thunderstorms also that showed the state's progress the job done, period." school will be free of drugs and measure adult literacy and the possible. -

Bossypants? One, Because the Name Two and a Half Men Was Already Taken

Acknowledgments I would like to gratefully thank: Kay Cannon, Richard Dean, Eric Gurian, John Riggi, and Tracy Wigfield for their eyes and ears. Dave Miner for making me do this. Reagan Arthur for teaching me how to do this. Katie Miervaldis for her dedicated service and Latvian demeanor. Tom Ceraulo for his mad computer skills. Michael Donaghy for two years of Sundays. Jeff and Alice Richmond for their constant loving encouragement and their constant loving interruption, respectively. Thank you to Lorne Michaels, Marc Graboff, and NBC for allowing us to reprint material. Contents Front Cover Image Welcome Dedication Introduction Origin Story Growing Up and Liking It All Girls Must Be Everything Delaware County Summer Showtime! That’s Don Fey Climbing Old Rag Mountain Young Men’s Christian Association The Windy City, Full of Meat My Honeymoon, or A Supposedly Fun Thing I’ll Never Do Again Either The Secrets of Mommy’s Beauty Remembrances of Being Very Very Skinny Remembrances of Being a Little Bit Fat A Childhood Dream, Realized Peeing in Jars with Boys I Don’t Care If You Like It Amazing, Gorgeous, Not Like That Dear Internet 30 Rock: An Experiment to Confuse Your Grandparents Sarah, Oprah, and Captain Hook, or How to Succeed by Sort of Looking Like Someone There’s a Drunk Midget in My House A Celebrity’s Guide to Celebrating the Birth of Jesus Juggle This The Mother’s Prayer for Its Daughter What Turning Forty Means to Me What Should I Do with My Last Five Minutes? Acknowledgments Copyright * Or it would be the biggest understatement since Warren Buffett said, “I can pay for dinner tonight.” Or it would be the biggest understatement since Charlie Sheen said, “I’m gonna have fun this weekend.” So, you have options. -

C:\Documents and Settings\Fre...N.Default\Cache\0\11

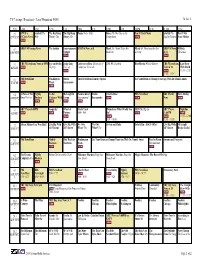

TV Listings Broadcast - Local Broadcast 94501 Fri, Jun. 8 PDT 6 PM 6:30 7 PM 7:30 8 PM 8:30 9 PM 9:30 10 PM 10:30 11 PM 11:30 2.1 KTVU 6 Seinfeld The The Big Bang The Big Bang House Better Half Bones The Hot Dog in the Ten O'Clock News Seinfeld The How I Met KTVUDT O'Clock News Wife Theory The Theory The Competition new English Patient Your Mother new 4.1 KRON 4 Evening News The Insider Entertainment KRON 4 News at 8 Monk Mr. Monk Takes His Monk Mr. Monk and the Red KRON 4 News 30 Rock KRONDT Tonight Medicine Herring at 11 Christmas new new 5.1 CBS 5 Eyewitness News at 6PM Eye on the Bay Judge Judy Undercover Boss University of CSI: NY Crushed Blue Bloods Whistle Blower CBS 5 Eyewitness Late Show KPIXDT new Daytrip: Tires of California, Riverside News at 11 With David new new 11:35 - 12:37 11:00 - 11:35 6.1 PBS NewsHour Washington Studio The Ed Sullivan Comedy Special Use Your Brain to Change Your Age With Dr. Daniel Amen KVIEDT new Week Sacramento new 6.2 A Place of Our Nightly To the McLaughlin Need to Know Studio Charlie Rose PBS NewsHour BBC World Tavis Smiley KVIEDT2 Own Week in Business Contrary With Group International Sacramento new new News new new new new new 7.1 ABC7 News 6:00PM Jeopardy! Wheel of Shark Tank Primetime: What Would You 20/20 The Big Lie ABC7 News Nightline KGODT new new Fortune 8:00 - 9:01 Do? new 11:00PM new new new new 11:35 - 12:00 9:01 - 10:00 11:00 - 11:35 7.2 Alyssa Milano Uses Wen Hair! Live Big With Live Big With We Owe We Owe Steven and Chris Total Gym - $14.95 Offer! Live Big With My Family KGODT2 Ali Vincent Ali Vincent What? The What? The Ali Vincent Recipe Rocks! 9.1 PBS NewsHour Nightly This Week in Washington Use Your Brain to Change Your Age With Dr. -

Japan's Pacific Campaign

2 Japan’s Pacific Campaign MAIN IDEA WHY IT MATTERS NOW TERMS & NAMES EMPIRE BUILDING Japan World War II established the • Isoroku •Douglas attacked Pearl Harbor in Hawaii United States as a leading player Yamamoto MacArthur and brought the United States in international affairs. •Pearl Harbor • Battle of into World War II. • Battle of Guadalcanal Midway SETTING THE STAGE Like Hitler, Japan’s military leaders also had dreams of empire. Japan’s expansion had begun in 1931. That year, Japanese troops took over Manchuria in northeastern China. Six years later, Japanese armies swept into the heartland of China. They expected quick victory. Chinese resistance, however, caused the war to drag on. This placed a strain on Japan’s economy. To increase their resources, Japanese leaders looked toward the rich European colonies of Southeast Asia. Surprise Attack on Pearl Harbor TAKING NOTES Recognizing Effects By October 1940, Americans had cracked one of the codes that the Japanese Use a chart to identify used in sending secret messages. Therefore, they were well aware of Japanese the effects of four major plans for Southeast Asia. If Japan conquered European colonies there, it could events of the war in the also threaten the American-controlled Philippine Islands and Guam. To stop the Pacific between 1941 and 1943. Japanese advance, the U.S. government sent aid to strengthen Chinese resistance. And when the Japanese overran French Indochina—Vietnam, Cambodia, and Laos—in July 1941, Roosevelt cut off oil shipments to Japan. Event Effect Despite an oil shortage, the Japanese continued their conquests. They hoped to catch the European colonial powers and the United States by surprise. -

The History Problem: the Politics of War

History / Sociology SAITO … CONTINUED FROM FRONT FLAP … HIRO SAITO “Hiro Saito offers a timely and well-researched analysis of East Asia’s never-ending cycle of blame and denial, distortion and obfuscation concerning the region’s shared history of violence and destruction during the first half of the twentieth SEVENTY YEARS is practiced as a collective endeavor by both century. In The History Problem Saito smartly introduces the have passed since the end perpetrators and victims, Saito argues, a res- central ‘us-versus-them’ issues and confronts readers with the of the Asia-Pacific War, yet Japan remains olution of the history problem—and eventual multiple layers that bind the East Asian countries involved embroiled in controversy with its neighbors reconciliation—will finally become possible. to show how these problems are mutually constituted across over the war’s commemoration. Among the THE HISTORY PROBLEM THE HISTORY The History Problem examines a vast borders and generations. He argues that the inextricable many points of contention between Japan, knots that constrain these problems could be less like a hang- corpus of historical material in both English China, and South Korea are interpretations man’s noose and more of a supportive web if there were the and Japanese, offering provocative findings political will to determine the virtues of peaceful coexistence. of the Tokyo War Crimes Trial, apologies and that challenge orthodox explanations. Written Anything less, he explains, follows an increasingly perilous compensation for foreign victims of Japanese in clear and accessible prose, this uniquely path forward on which nationalist impulses are encouraged aggression, prime ministerial visits to the interdisciplinary book will appeal to sociol- to derail cosmopolitan efforts at engagement. -

Downloads of Technical Information

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2018 Nuclear Spaces: Simulations of Nuclear Warfare in Film, by the Numbers, and on the Atomic Battlefield Donald J. Kinney Follow this and additional works at the DigiNole: FSU's Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected] FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF ARTS AND SCIENCES NUCLEAR SPACES: SIMULATIONS OF NUCLEAR WARFARE IN FILM, BY THE NUMBERS, AND ON THE ATOMIC BATTLEFIELD By DONALD J KINNEY A Dissertation submitted to the Department of History in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy 2018 Donald J. Kinney defended this dissertation on October 15, 2018. The members of the supervisory committee were: Ronald E. Doel Professor Directing Dissertation Joseph R. Hellweg University Representative Jonathan A. Grant Committee Member Kristine C. Harper Committee Member Guenter Kurt Piehler Committee Member The Graduate School has verified and approved the above-named committee members, and certifies that the dissertation has been approved in accordance with university requirements. ii For Morgan, Nala, Sebastian, Eliza, John, James, and Annette, who all took their turns on watch as I worked. iii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to thank the members of my committee, Kris Harper, Jonathan Grant, Kurt Piehler, and Joseph Hellweg. I would especially like to thank Ron Doel, without whom none of this would have been possible. It has been a very long road since that afternoon in Powell's City of Books, but Ron made certain that I did not despair. Thank you. iv TABLE OF CONTENTS Abstract..............................................................................................................................................................vii 1.