The Complexities of Latina Sexuality on Ugly Betty Tanya González

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Football Team Went Down in Bitter Defeat at the Hands of the Strong New Haven Team

mm m 1' i>: i'S. 9 r '-V.'SS i i . ■ \ M ! i : • * . '•4$M m . tk rn t;> s I 9 WISTARIAN | ! I: ' 1 -* '■>. "• ' A • vV'-io'r s'.'"i'.^/'-^: ';>> TA V-' V'.: 'i*fvA 3$g mm«pi ■filllll®:-v ■>-. 'jS’V v' v -V •• 'f I i 1 Wistarian 1959 University of Bridgeport Bridgeport, Connecticut Staff r \ i! ; Editor Charles S. Huestis Assistant Editor John B. Stewart, III V;. :«***. ^ : Art Editor Robert Stumpek i. ! • Copy Editor Sally Ann Podufaly T, - & ■ i — . Advisor Victor Swain I *» Art Advisor Sybil Wilson > I- •t els \} M U»-T«ip»^9 I •t. •? = . ‘ V . • • .. • - - • t i t ■ 5 •, -----------I — v .... P L: r ■ «« m "" > N. / «' i ■. L 'KH A ,-iii 1 : V T vV i =U ■ ’ \ 5 tsrThe title of this article, slightly altered, I becomes the keyword of our generation. ' nForward. The word itself connotes the rest- 04 0 less undercurrent that has intensified man's recent advancement. We are now riding a crest of inventive achievement. New \rs ideas have spurred manufacture and trans portation. Very recently men have begun to muster their frail strength and utilize their intelligence to probe the mysteries of the universe. Gropingly, steadily, man continues to extend his mastery over the elements. The world we are about to enter is brilliant, tense, and challenging; it is a place where new achievements and new dangers are born simultaneously. During this time of explosive advances, we here at the University have lived exact- ly the same collegiate pattern which our predecessors lived years ago. We studied untii daybreak; then fortified with black coffcwe went doggedly to class to be tested: v/e shelved our books in favor of the bj.ketball games, "bull" sessions, or do* when the threat of mental combat was loss imminent; we spent countless hours discussing the administration, the world situation, the faculty, our classmates. -

Echoes of Memory Volume 9

Echoes of Memory Volume 9 CONTENTS JACQUELINE MENDELS BIRN MICHEL MARGOSIS The Violins of Hope ...................................................2 In Transit, Spain ........................................................ 28 RUTH COHEN HARRY MARKOWICZ Life Is Good ....................................................................3 A Letter to the Late Mademoiselle Jeanne ..... 34 Sunday Lunch at Charlotte’s House ................... 36 GIDEON FRIEDER True Faith........................................................................5 ALFRED MÜNZER Days of Remembrance in Rymanow ..................40 ALBERT GARIH Reunion in Ebensee ................................................. 43 Flory ..................................................................................8 My Mother ..................................................................... 9 HALINA YASHAROFF PEABODY Lying ..............................................................................46 PETER GOROG A Gravestone for Those Who Have None .........12 ALFRED TRAUM A Three-Year-Old Saves His Mother ..................14 The S.S. Zion ...............................................................49 The Death Certificate That Saved Vienna, Chanukah 1938 ...........................................52 Our Lives ..................................................................................... 16 SUSAN WARSINGER JULIE KEEFER Bringing the Lessons Home ................................. 54 Did He Know I Was Jewish? ...................................18 Feeling Good ...............................................................55 -

The Analysis of Transition in Woman Social Status—Comparing Cinderella with Ugly Betty

ISSN 1798-4769 Journal of Language Teaching and Research, Vol. 1, No. 5, pp. 746-752, September 2010 © 2010 ACADEMY PUBLISHER Manufactured in Finland. doi:10.4304/jltr.1.5.746-752 The Analysis of Transition in Woman Social Status—Comparing Cinderella with Ugly Betty Tiping Su Huaiyin Normal University, Huai’an, China Email: [email protected] Qinyi Xue Huaiyin Normal University, Huai’an, China Email: [email protected] Abstract—Cinderella, a perfect fairly tale girl has been widely known to the world. Its popularity reveals the universal Cinderella Complex hidden behind the woman status. My thesis focuses its attention on the transition in woman status. First, it looks into the Cinderella paradigm as well as its complex in reality. Second, it finds the transcendence in modern Cinderella. The last part pursues the development of women status’ improvement. In current study, seldom people make comparisons between Cinderella and Ugly Betty. With its comparison and the exploration of feminism, it can be reached that woman status have been greatly improved under the influence of different factors like economic and political. And as a modern woman lives in the new century, she has to be independent in economy and optimistic in spirit. Index Terms—Cinderella Complex, Ugly Betty, feminist movement, feminine consciousness, women status I. INTRODUCTION Cinderella, a beautiful fairy tale widely known around the world, has become a basic literary archetype in the world literature. Its popularity reveals the universal Cinderella Complex hidden behind the human’s consciousness. With the development of feminine, women came to realize their inner power and the meaning of life. -

Shawn Paper Ace Editor

SHAWN PAPER ACE EDITOR FEATURES THE BROKEN HEARTS GALLERY Natalie Krinsky Tri-Star Pictures / No Trace Camping THAT AWKWARD MOMENT Tom Gormican Focus Features SHOULD’VE BEEN ROMEO Marc Bennett Phillybrook Films WHAT IS IT? Crispin Glover Volcanic Eruptions TELEVISION IN FROM THE COLD Ami Canaan Mann, Netflix / Silver Lining Entertainment Paco Cabezas & Birgitte Staermose SWEET TOOTH Jim Mickle, Robyn Grace Team Downey / Warner Bros Television / Netflix & Toa Fraser WHAT WE DO IN THE SHADOWS Taika Waititi, Taika Waititi, Jemaine Clement, Paul Simms / FX Official Selection, SXSW Film Festival (2019) Jemaine Clement, Jason Woliner & Jackie Van Beck CRASHING (Seasons 2 & 3) Judd Apatow, Judd Apatow, Pete Holmes, Judah Miller / HBO Gillian Robespierre, Oren Brimer & Ryan McFaul VEEP (Season 5) Various David Mandel, Julia Louis-Dreyfus / HBO Nominated, Outstanding Single-Camera Picture Editing for a Comedy Series, Primetime Emmy Awards (2012) Nominated, Best Edited Half-Hour Series for Television, ACE Eddie Awards (2012) I FEEL BAD (Pilot) Julie Anne Robinson Amy Poehler / Paper Kite Productions / NBC MOZART IN THE JUNGLE (Season 2) Paul Weitz Paul Weitz, Jason Schwartzman, Roman Coppola / Amazon GIRLS (Seasons 1, 2, 3 & 4) Richard Shepard Lena Dunham, Judd Apatow, Jenni Konner / HBO Jamie Babbit FRIENDS FROM COLLEGE Nicholas Stoller Nicholas Stoller, Francesca Delbanco / Netflix SANTA CLARITA DIET Ruben Fleischer Victor Fresco, Tracy Katsky /Netflix MARRY ME (Pilot) Seth Gordon David Caspe, Jamie Tarses / NBC GAFFIGAN (Pilot) Seth Gordon Jim -

LOGLINE January / February 2020 Volume 13: Number 1 the Screenwriter’S Ezine

LOGLINE January / February 2020 Volume 13: Number 1 The Screenwriter’s eZine Published by: Letter From the Editor The PAGE International Screenwriting Awards It’s a new year and a new day for screenwriters around the 7190 W. Sunset Blvd. #610 Hollywood, CA 90046 world! Here at PAGE HQ we hope you had a wonderful holiday www.pageawards.com season, feel recharged, and are ready to take the next step in your writing career. In this issue: One way to potentially make a major breakthrough: the 2020 LO PAGE Awards contest. Our Early Entry Deadline is now just 1 Latest News From two weeks away – Monday, January 20 – and with our low the PAGE Awards Early Entry Discount rates, now is the very best time to get your script in the running for one of this year’s awards. Many past PAGE Award winners have optioned and sold their scripts, been signed 2 The Writer’s by Hollywood representatives, and built highly successful careers in the industry. Perspective You could be next! Is It Ever “Too Late” to Chase Your Dream? As we begin lucky Volume 13 of the bimonthly LOGLINE eZine, we welcome new Erin Muroski readers to the publication designed to share industry intel and advice with all writers. First, 2019 PAGE Award winner Erin Muroski reflects on her rush to find success, and how she got over it. PAGE Judge Genie Joseph introduces us to three prevailing story 3 The Judge’s P.O.V. styles that inform a film from page to screen. Script consultant Ray Morton strikes a Three Styles of Story: balance between art and commerce and Dr. -

SUSPENSE MAGAZINE Spring 2021 / Vol

Suspense, Mystery, Horror and Thriller Fiction SPRING 2021 A Suspenseful Spring has Sprung! GREG F. GIFUNE DIETRICH KALTEIS DON BENTLEY Inspired by Actual Events JONATHAN KELLERMAN with Parris Afton Bonds J.A. JANCE JOSEPH BADAL Get a Sneak Peek of Head Back to Harper’s Island “BLACKOUT" with JOHN RAAB MARCO CAROCARI From the Editor How is everyone doing out there? I must say, it’s been quite the year thus far. We have mostly been locked down for so long, we’ve been streaming everything we can possibly watch. We have also, hopefully, read more books this year than in the past. CREDITS It’s now 2021, and time to turn the page John Raab on the worst year most of us has ever lived President & Chairman through. We want to remember the people Shannon Raab who have died during this pandemic and Creative Director give our prayers to all the families that Abigail Peralta have suffered such a horrible loss. Yes, it’s not a “far out” thing to say 2020 was unlike Vice President, Editorial Dept. anything we have ever seen before…but, with luck, it’s something we will never see again. We see the light at the end of the tunnel. Our medical professionals are working hard Amy Lignor Editor to ensure the vaccines get to everyone, and we can finally enjoy the writing conferences we’ve missed so much. Thank you to one and all. Contributors In case you’ve run out of things to watch, here are the top five hidden gems you might Susan Santangelo Kaye George have missed when they were originally released: Weldon Burge 5. -

Bossypants? One, Because the Name Two and a Half Men Was Already Taken

Acknowledgments I would like to gratefully thank: Kay Cannon, Richard Dean, Eric Gurian, John Riggi, and Tracy Wigfield for their eyes and ears. Dave Miner for making me do this. Reagan Arthur for teaching me how to do this. Katie Miervaldis for her dedicated service and Latvian demeanor. Tom Ceraulo for his mad computer skills. Michael Donaghy for two years of Sundays. Jeff and Alice Richmond for their constant loving encouragement and their constant loving interruption, respectively. Thank you to Lorne Michaels, Marc Graboff, and NBC for allowing us to reprint material. Contents Front Cover Image Welcome Dedication Introduction Origin Story Growing Up and Liking It All Girls Must Be Everything Delaware County Summer Showtime! That’s Don Fey Climbing Old Rag Mountain Young Men’s Christian Association The Windy City, Full of Meat My Honeymoon, or A Supposedly Fun Thing I’ll Never Do Again Either The Secrets of Mommy’s Beauty Remembrances of Being Very Very Skinny Remembrances of Being a Little Bit Fat A Childhood Dream, Realized Peeing in Jars with Boys I Don’t Care If You Like It Amazing, Gorgeous, Not Like That Dear Internet 30 Rock: An Experiment to Confuse Your Grandparents Sarah, Oprah, and Captain Hook, or How to Succeed by Sort of Looking Like Someone There’s a Drunk Midget in My House A Celebrity’s Guide to Celebrating the Birth of Jesus Juggle This The Mother’s Prayer for Its Daughter What Turning Forty Means to Me What Should I Do with My Last Five Minutes? Acknowledgments Copyright * Or it would be the biggest understatement since Warren Buffett said, “I can pay for dinner tonight.” Or it would be the biggest understatement since Charlie Sheen said, “I’m gonna have fun this weekend.” So, you have options. -

C:\Documents and Settings\Fre...N.Default\Cache\0\11

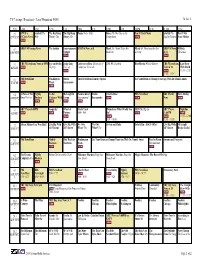

TV Listings Broadcast - Local Broadcast 94501 Fri, Jun. 8 PDT 6 PM 6:30 7 PM 7:30 8 PM 8:30 9 PM 9:30 10 PM 10:30 11 PM 11:30 2.1 KTVU 6 Seinfeld The The Big Bang The Big Bang House Better Half Bones The Hot Dog in the Ten O'Clock News Seinfeld The How I Met KTVUDT O'Clock News Wife Theory The Theory The Competition new English Patient Your Mother new 4.1 KRON 4 Evening News The Insider Entertainment KRON 4 News at 8 Monk Mr. Monk Takes His Monk Mr. Monk and the Red KRON 4 News 30 Rock KRONDT Tonight Medicine Herring at 11 Christmas new new 5.1 CBS 5 Eyewitness News at 6PM Eye on the Bay Judge Judy Undercover Boss University of CSI: NY Crushed Blue Bloods Whistle Blower CBS 5 Eyewitness Late Show KPIXDT new Daytrip: Tires of California, Riverside News at 11 With David new new 11:35 - 12:37 11:00 - 11:35 6.1 PBS NewsHour Washington Studio The Ed Sullivan Comedy Special Use Your Brain to Change Your Age With Dr. Daniel Amen KVIEDT new Week Sacramento new 6.2 A Place of Our Nightly To the McLaughlin Need to Know Studio Charlie Rose PBS NewsHour BBC World Tavis Smiley KVIEDT2 Own Week in Business Contrary With Group International Sacramento new new News new new new new new 7.1 ABC7 News 6:00PM Jeopardy! Wheel of Shark Tank Primetime: What Would You 20/20 The Big Lie ABC7 News Nightline KGODT new new Fortune 8:00 - 9:01 Do? new 11:00PM new new new new 11:35 - 12:00 9:01 - 10:00 11:00 - 11:35 7.2 Alyssa Milano Uses Wen Hair! Live Big With Live Big With We Owe We Owe Steven and Chris Total Gym - $14.95 Offer! Live Big With My Family KGODT2 Ali Vincent Ali Vincent What? The What? The Ali Vincent Recipe Rocks! 9.1 PBS NewsHour Nightly This Week in Washington Use Your Brain to Change Your Age With Dr. -

Tv Land Adds More Stars to Its Stunning Talent Roster As Two New Pilots Finalize Casting

TV LAND ADDS MORE STARS TO ITS STUNNING TALENT ROSTER AS TWO NEW PILOTS FINALIZE CASTING Elliott Gould And Missi Pyle Join Ben Falcone, Jay Mohr, Josh Cooke, Ellen Woglom, Geoff Pierson And Kelen Coleman In Multi- And Single-Camera Pilots For The Network August 23, 2012 – Los Angeles, CA – Elliott Gould (“Friends”) and Missi Pyle (“The Artist”) have joined previously reported stars Ben Falcone, Jay Mohr, Josh Cooke, Ellen Woglom, Geoff Pierson and Kelen Coleman in TV Land’s two new pilots, it was announced today by Keith Cox, Executive Vice President, Development and Original Programming for TV Land. Falcone (“Bridesmaids”) will play the lead in “I’m Not Dead Yet” (working title) as Sandy Lazarus, a driving instructor who, after learning he has a potentially fatal heart condition, decides to start speaking his mind and grab life by the horns. This personality change is greeted by shock and skepticism from his wife (Pyle), father (Gould) and children. “I’m Not Dead Yet” will shoot in September. TV Land’s second pilot, “Brothers-in-Law” (working title), will star Mohr (“Last Comic Standing”), Cooke (“Better With You”), Woglom (“Outlaw”) Pierson (“24”) and Coleman (“The Newsroom”). The pilot focuses on the family dynamic between Neil (Cooke) and his wife Cheska (Coleman) as they adjust to Van (Mohr), the eccentric fiancé of Cheska’s twin sister Maddie (Woglom). Pierson stars as Tom, the family patriarch, whose instant bond with Van makes Neil jealous and annoyed. On top of that, the sisters constantly encourage Neil and Van to form a friendship, even though the men have absolutely nothing in common. -

Public Opinion and Discourse on the Intersection of LGBT Issues and Race the Opportunity Agenda

Opinion Research & Media Content Analysis Public Opinion and Discourse on the Intersection of LGBT Issues and Race The Opportunity Agenda Acknowledgments This research was conducted by Loren Siegel (Executive Summary, What Americans Think about LGBT People, Rights and Issues: A Meta-Analysis of Recent Public Opinion, and Coverage of LGBT Issues in African American Print and Online News Media: An Analysis of Media Content); Elena Shore, Editor/Latino Media Monitor of New America Media (Coverage of LGBT Issues in Latino Print and Online News Media: An Analysis of Media Content); and Cheryl Contee, Austen Levihn- Coon, Kelly Rand, Adriana Dakin, and Catherine Saddlemire of Fission Strategy (Online Discourse about LGBT Issues in African American and Latino Communities: An Analysis of Web 2.0 Content). Loren Siegel acted as Editor-at-Large of the report, with assistance from staff of The Opportunity Agenda. Christopher Moore designed the report. The Opportunity Agenda’s research on the intersection of LGBT rights and racial justice is funded by the Arcus Foundation. The statements made and views expressed are those of The Opportunity Agenda. Special thanks to those who contributed to this project, including Sharda Sekaran, Shareeza Bhola, Rashad Robinson, Kenyon Farrow, Juan Battle, Sharon Lettman, Donna Payne, and Urvashi Vaid. About The Opportunity Agenda The Opportunity Agenda was founded in 2004 with the mission of building the national will to expand opportunity in America. Focused on moving hearts, minds, and policy over time, the organization works with social justice groups, leaders, and movements to advance solutions that expand opportunity for everyone. Through active partnerships, The Opportunity Agenda synthesizes and translates research on barriers to opportunity and corresponding solutions; uses communications and media to understand and influence public opinion; and identifies and advocates for policies that improve people’s lives. -

Canadian Canada $7 Spring 2020 Vol.22, No.2 Screenwriter Film | Television | Radio | Digital Media

CANADIAN CANADA $7 SPRING 2020 VOL.22, NO.2 SCREENWRITER FILM | TELEVISION | RADIO | DIGITAL MEDIA The Law & Order Issue The Detectives: True Crime Canadian-Style Peter Mitchell on Murdoch’s 200th ep Floyd Kane Delves into class, race & gender in legal PM40011669 drama Diggstown Help Producers Find and Hire You Update your Member Directory profile. It’s easy. Login at www.wgc.ca to get started. Questions? Contact Terry Mark ([email protected]) Member Directory Ad.indd 1 3/6/19 11:25 AM CANADIAN SCREENWRITER The journal of the Writers Guild of Canada Vol. 22 No. 2 Spring 2020 Contents ISSN 1481-6253 Publication Mail Agreement Number 400-11669 Cover Publisher Maureen Parker Diggstown Raises Kane To New Heights 6 Editor Tom Villemaire [email protected] Creator and showrunner Floyd Kane tackles the intersection of class, race, gender and the Canadian legal system as the Director of Communications groundbreaking CBC drama heads into its second season Lana Castleman By Li Robbins Editorial Advisory Board Michael Amo Michael MacLennan Features Susin Nielsen The Detectives: True Crime Canadian-Style 12 Simon Racioppa Rachel Langer With a solid background investigating and writing about true President Dennis Heaton (Pacific) crime, showrunner Petro Duszara and his team tell us why this Councillors series is resonating with viewers and lawmakers alike. Michael Amo (Atlantic) By Matthew Hays Marsha Greene (Central) Alex Levine (Central) Anne-Marie Perrotta (Quebec) Murdoch Mysteries’ Major Milestone 16 Lienne Sawatsky (Central) Andrew Wreggitt (Western) Showrunner Peter Mitchell reflects on the successful marriage Design Studio Ours of writing and crew that has made Murdoch Mysteries an international hit, fuelling 200+ eps. -

Art Direction INDUSTRY EXPERIENCE

[email protected] Production Design/ Art Direction 323-359-2483 kstewardstudio.com INDUSTRY EXPERIENCE FEATURE FILM & TELEVISION AMY’S BROTHER (Pilot) PRODUCTION DESIGN Director: Beth McCarthy-Miller Exec Producer: Melissa McCarthy Producer: Chris Larson-Nitzche KIDDING S1 (Showtime Series) SUPERVISING ART DIRECTOR PD: Maxwell Orgell Producer: Sarah Caplan THE NEWSROOM S2,3-(HBO) ART DIR / PROD DESIGNER Exec. Producer: Alan Poul Exec. Producer: Aaron Sorkin PD: (Season 1,2) Richard Hoover PD: (Season 3) Karen Steward Golden Globe Nomination 2013 for Best Drama Series ADG Nominated: Best Art Direction McFARLAND (Disney Feature Film) SUPERVISING ART DIRECTOR Director: Niki Caro Producer: Mario Iscovich PD: Richard Hoover Image Award 2016 OLYMPUS HAS FALLEN (Millinium Feature Film) SUPERVISING ART DIRECTOR Director: Antoine Fuqua Producer: Ed Cathell lll Production Designer: Derek Hill THE HANDLER (CBS/Viacom TV Series EP1) PRODUCTION DESIGN Producers: Sean Ryerson & Mick Jackson Director: Lou Antonio WIZARD OF ID (Short -Feature Film) PRODUCTION DESIGN Director: Nancy Hower Producer: Mark Seldis JACK RYAN (Amazon) (LA Unit) ART DIRECTOR Paramount Overseas Productions Inc PD: Zack Grobler Producer: Carlton Cues DR. STRANGE (Additional Photography) ART DIRECTOR Marvel/ Disney (Feature Film) PD: Shepherd Frankel Karen Steward INDUSTRY EXPERIENCE Page 2 FEATURE FILM & TELEVISION (CON’T) VEEP S5 (HBO Series) ART DIRECTOR Producer: Dave Mandell PD: James Gloster Emmy Nominated ANIMAL KINGDOM (Animal Practice) (NBC Pilot) ART DIRECTOR Producers: