Appreciating Classic Experiments Douglas Allchin Editor, Ships

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

書 名 等 発行年 出版社 受賞年 備考 N1 Ueber Das Zustandekommen Der

書 名 等 発行年 出版社 受賞年 備考 Ueber das Zustandekommen der Diphtherie-immunitat und der Tetanus-Immunitat bei thieren / Emil Adolf N1 1890 Georg thieme 1901 von Behring N2 Diphtherie und tetanus immunitaet / Emil Adolf von Behring und Kitasato 19-- [Akitomo Matsuki] 1901 Malarial fever its cause, prevention and treatment containing full details for the use of travellers, University press of N3 1902 1902 sportsmen, soldiers, and residents in malarious places / by Ronald Ross liverpool Ueber die Anwendung von concentrirten chemischen Lichtstrahlen in der Medicin / von Prof. Dr. Niels N4 1899 F.C.W.Vogel 1903 Ryberg Finsen Mit 4 Abbildungen und 2 Tafeln Twenty-five years of objective study of the higher nervous activity (behaviour) of animals / Ivan N5 Petrovitch Pavlov ; translated and edited by W. Horsley Gantt ; with the collaboration of G. Volborth ; and c1928 International Publishing 1904 an introduction by Walter B. Cannon Conditioned reflexes : an investigation of the physiological activity of the cerebral cortex / by Ivan Oxford University N6 1927 1904 Petrovitch Pavlov ; translated and edited by G.V. Anrep Press N7 Die Ätiologie und die Bekämpfung der Tuberkulose / Robert Koch ; eingeleitet von M. Kirchner 1912 J.A.Barth 1905 N8 Neue Darstellung vom histologischen Bau des Centralnervensystems / von Santiago Ramón y Cajal 1893 Veit 1906 Traité des fiévres palustres : avec la description des microbes du paludisme / par Charles Louis Alphonse N9 1884 Octave Doin 1907 Laveran N10 Embryologie des Scorpions / von Ilya Ilyich Mechnikov 1870 Wilhelm Engelmann 1908 Immunität bei Infektionskrankheiten / Ilya Ilyich Mechnikov ; einzig autorisierte übersetzung von Julius N11 1902 Gustav Fischer 1908 Meyer Die experimentelle Chemotherapie der Spirillosen : Syphilis, Rückfallfieber, Hühnerspirillose, Frambösie / N12 1910 J.Springer 1908 von Paul Ehrlich und S. -

Biography: Sir Benjamin Thompson, Count Rumford

Biography: Christiaan Eijkman As a debilitating and, sometimes, fatal disease spread across the West Indies in the late nineteenth century, one man was devoting all his efforts to finding a cure for it. This man was Christiaan Eijkman, and the disease was beriberi. Through careful experimentation, including a massive study of over two-hundred-and-eighty thou- sand prisoners in Javanese prisons, Eijkman managed to find the cure. Using the findings of Eijkman’s study, scientists were able to isolate a nutrient called thiamin, also known as vitamin B1. Eijkman had, through his research, formed the basis for understanding the role of vitamins in nutrition, for which he received the Nobel Prize, together with Sir Frederick Hopkins, late in his life. Christiaan Eijkman was born on August 11, 1858 muscle weakness. Patients suffering from beriberi in the small town of Nijkerk, in The Netherlands. He commonly lose their sense of feeling and control of was the seventh child of Christiaan Eijkman and their limbs, often leading to paralysis. In some cases, Johanna Alida Pool. Christiaan’s father worked as a fluid collects in the legs, taxing the circulatory system, headmaster at the local school. enlarging the heart, and causing heart failure. The When he was only a few years old, his family relo- disease can be fatal. cated to Zaandam, a larger city in the Netherlands. In Beriberi was increasingly becoming a national se- Zaandam, he began his education at his father’s curity issue for the Netherlands. The mounting inci- school. He progressed in his studies with ease and dence of the disease among the soldiers and sailors passed his university-entrance exams in 1875, at the had already resulted in the Dutch government having age of 17. -

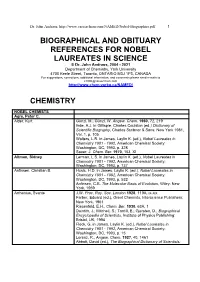

Biographical References for Nobel Laureates

Dr. John Andraos, http://www.careerchem.com/NAMED/Nobel-Biographies.pdf 1 BIOGRAPHICAL AND OBITUARY REFERENCES FOR NOBEL LAUREATES IN SCIENCE © Dr. John Andraos, 2004 - 2021 Department of Chemistry, York University 4700 Keele Street, Toronto, ONTARIO M3J 1P3, CANADA For suggestions, corrections, additional information, and comments please send e-mails to [email protected] http://www.chem.yorku.ca/NAMED/ CHEMISTRY NOBEL CHEMISTS Agre, Peter C. Alder, Kurt Günzl, M.; Günzl, W. Angew. Chem. 1960, 72, 219 Ihde, A.J. in Gillispie, Charles Coulston (ed.) Dictionary of Scientific Biography, Charles Scribner & Sons: New York 1981, Vol. 1, p. 105 Walters, L.R. in James, Laylin K. (ed.), Nobel Laureates in Chemistry 1901 - 1992, American Chemical Society: Washington, DC, 1993, p. 328 Sauer, J. Chem. Ber. 1970, 103, XI Altman, Sidney Lerman, L.S. in James, Laylin K. (ed.), Nobel Laureates in Chemistry 1901 - 1992, American Chemical Society: Washington, DC, 1993, p. 737 Anfinsen, Christian B. Husic, H.D. in James, Laylin K. (ed.), Nobel Laureates in Chemistry 1901 - 1992, American Chemical Society: Washington, DC, 1993, p. 532 Anfinsen, C.B. The Molecular Basis of Evolution, Wiley: New York, 1959 Arrhenius, Svante J.W. Proc. Roy. Soc. London 1928, 119A, ix-xix Farber, Eduard (ed.), Great Chemists, Interscience Publishers: New York, 1961 Riesenfeld, E.H., Chem. Ber. 1930, 63A, 1 Daintith, J.; Mitchell, S.; Tootill, E.; Gjersten, D., Biographical Encyclopedia of Scientists, Institute of Physics Publishing: Bristol, UK, 1994 Fleck, G. in James, Laylin K. (ed.), Nobel Laureates in Chemistry 1901 - 1992, American Chemical Society: Washington, DC, 1993, p. 15 Lorenz, R., Angew. -

Balcomk41251.Pdf (558.9Kb)

Copyright by Karen Suzanne Balcom 2005 The Dissertation Committee for Karen Suzanne Balcom Certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: Discovery and Information Use Patterns of Nobel Laureates in Physiology or Medicine Committee: E. Glynn Harmon, Supervisor Julie Hallmark Billie Grace Herring James D. Legler Brooke E. Sheldon Discovery and Information Use Patterns of Nobel Laureates in Physiology or Medicine by Karen Suzanne Balcom, B.A., M.L.S. Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Texas at Austin August, 2005 Dedication I dedicate this dissertation to my first teachers: my father, George Sheldon Balcom, who passed away before this task was begun, and to my mother, Marian Dyer Balcom, who passed away before it was completed. I also dedicate it to my dissertation committee members: Drs. Billie Grace Herring, Brooke Sheldon, Julie Hallmark and to my supervisor, Dr. Glynn Harmon. They were all teachers, mentors, and friends who lifted me up when I was down. Acknowledgements I would first like to thank my committee: Julie Hallmark, Billie Grace Herring, Jim Legler, M.D., Brooke E. Sheldon, and Glynn Harmon for their encouragement, patience and support during the nine years that this investigation was a work in progress. I could not have had a better committee. They are my enduring friends and I hope I prove worthy of the faith they have always showed in me. I am grateful to Dr. -

Dr Hugh Riordan Vitamin C Maverick Slides 1 - 45 O

Riordan Clinic IVC Academy Dr Hugh Riordan Vitamin C Maverick Slides 1 - 45 O © Riordan Clinic 2018 Dr. Hugh Riordan Vitamin C Maverick Ron Hunninghake M.D. Chief Medical Officer Riordan Clinic “One man with courage makes a majority.” Andrew Jackson Riordan Clinic www.riordanclinic.org Dedication • Dr. Hugh D. Riordan • Founder of Riordan Clinic • The Hugh D. Riordan Professorship in Orthomolecular Medicine • The 45th endowed professorship at Kansas Univ. School of Medicine 1932 - 2005 “The Hugh D. Riordan, MD, Professorship in Orthomolecular Medicine at KU Endowment honors the memory of Riordan, a pioneer in the field of complementary and alternative medicine, who died in January of 2005. He was a strong supporter of orthomolecular medicine, the practice of preventing and treating disease by providing the body with optimal amounts of natural substances.” KUMC News Bulletin Continuing Pauling’s Legacy Orthomolecular is the “right molecule” - Linus Pauling, PhD • Two-time Nobel Prize winner • Molecular Biologist • Coined the term “Orthomolecular” 1968 Science* article “Orthomolecular Psychiatry” *www.orthomolecular.org Hall of Fame 2004 1901 - 1994 “In the fields of observation… chance favors the prepared mind.” Dans les champs de l'observation le hasard ne favorise que les esprits préparés. Louis Pasteur 1822 - 1895 The Island of Curacao 1492 • Legend has it that several sailors from Christopher Columbus’ voyage to the new world developed scurvy • Feeling very sick and referring not to die at sea, they were dropped off on an uncharted Caribbean Island • Months later, the returning crew were all shocked and surprised to see these men, who were thought to be surely dead, waving to them from the shores, alive and healthy! • The island was named Curacao, meaning Cure. -

Eijkman Case Study

Of Rice and Men by Douglas Allchin Meet Christiaan Eijkman, who shared the Nobel Prize in Medicine in 1928. Today, we are going to journey with him on the mission of medical research that led to his award. The year was 1886. It was October. Eijkman embarked with two other doctors from the Netherlands. Their destination was the small island of Java, almost halfway around the globe, now part of Indonesia. They passed through the Suez Canal--only opened a few years earlier-- and arrived a few weeks later. Java was part of the Dutch East Indies, one of many important trading colonies around the world. On Java and the surrounding islands, the doctors could be fascinated by the exotic forests, with trees likely taller. There are dense thickets of fibrous rattan vines, harvested by the Javanese and exported to Japan to make tatami mats. Many crops made the East Indies valuable as a colony to the Netherlands: sugar cane, coffee, cacao and indigo. Many trees had been cleared to grow the crops, imported from other tropical regions. Life on Java would not be the same for the three doctors, even in the Dutch community of Batavia. The tropical heat was everywhere. A typical Dutchman would also have to develop a taste for rice, a staple in this region of Asia. Eijkman, age 28, had seen the sights of Java before while serving as an officer for the Dutch Army. However, after two years he had contracted malaria and returned to the Netherlands. Malaria was one of many diseases common in the tropics. -

Nobel Laureates in Physiology Or Medicine

All Nobel Laureates in Physiology or Medicine 1901 Emil A. von Behring Germany ”for his work on serum therapy, especially its application against diphtheria, by which he has opened a new road in the domain of medical science and thereby placed in the hands of the physician a victorious weapon against illness and deaths” 1902 Sir Ronald Ross Great Britain ”for his work on malaria, by which he has shown how it enters the organism and thereby has laid the foundation for successful research on this disease and methods of combating it” 1903 Niels R. Finsen Denmark ”in recognition of his contribution to the treatment of diseases, especially lupus vulgaris, with concentrated light radiation, whereby he has opened a new avenue for medical science” 1904 Ivan P. Pavlov Russia ”in recognition of his work on the physiology of digestion, through which knowledge on vital aspects of the subject has been transformed and enlarged” 1905 Robert Koch Germany ”for his investigations and discoveries in relation to tuberculosis” 1906 Camillo Golgi Italy "in recognition of their work on the structure of the nervous system" Santiago Ramon y Cajal Spain 1907 Charles L. A. Laveran France "in recognition of his work on the role played by protozoa in causing diseases" 1908 Paul Ehrlich Germany "in recognition of their work on immunity" Elie Metchniko France 1909 Emil Theodor Kocher Switzerland "for his work on the physiology, pathology and surgery of the thyroid gland" 1910 Albrecht Kossel Germany "in recognition of the contributions to our knowledge of cell chemistry made through his work on proteins, including the nucleic substances" 1911 Allvar Gullstrand Sweden "for his work on the dioptrics of the eye" 1912 Alexis Carrel France "in recognition of his work on vascular suture and the transplantation of blood vessels and organs" 1913 Charles R. -

Ssfaoggi 201306

SOCIETA’ DI SCIENZE FARMACOLOGICHE APPLICATE SOCIETY FOR APPLIED PHARMACOLOGICAL SSFAoggi SCIENCES Notiziario di Medicina Farmaceutica Giugno 2013 Bimestrale della Società di Scienze Farmacologiche Applicate Fondata nel 1964 numero 37 Dove sono i nuovi antibiotici? Sommario: La comunità mondiale sta correndo un grosso rischio: questo ci ricordano due editoriali, Editoriale 1 pubblicati su The Lancet e sul British Medical Journal, che riportiamo alle pagine 21 e 22. La resistenza agli antibiotici è un grave problema: The Lancet ci ricorda che fu addirittura Novità in Farmacovigilanza messa in evidenza dallo stesso Alexander Fleming nel 1945, il quale temeva che l’abuso Parte prima 2 della penicillina potesse selezionare ceppi resistenti. Il British Medical Journal evidenzia che molte pratiche mediche e chirurgiche (dall’uso Novità in Farmacovigilanza della chemioterapia agli interventi invasivi in ortopedia e cardiochirurgia) sono possibili Parte seconda 4 grazie alla profilassi con antibiotici. E quindi, la resistenza agli antibiotici non è un solo un problema degli infettivologi, ma sta diventando un problema dei chirurghi, degli oncologi, e Il Decreto Balduzzi 6 di tutto il sistema sanitario. Alcune previsioni sono drammatiche: l’intervento di protesi dell’anca, che è diventato una Farmaci a brevetto scaduto 12 routine per la popolazione anziana, potrebbe essere colpito in modo significativo da com- plicanze infettive, passando dall’1% dei pazienti di oggi fino al 40%-50% dei pazienti nel Affari Istituzionali 12 prossimo futuro, con oltre un terzo di essi in pericolo di vita. Uno scenario davvero preoc- 5a Edizione Master Bicocca 13 cupante. Di fronte a queste previsioni, che ci vengono ormai ripetute ad intervalli regolari, stupisce Master Bicocca 2013: i numeri 13 la mancanza di incentivi per la ricerca di nuovi antibiotici. -

Albert Szent-Györgyi (Pronounced Like "Saint Georgie") Earned Recognition for His Biochemical Work on Vitamin C, Muscle and Energy in the Cell

forthcoming in New Dictionary of Scientific Biography Szent-Györgyi, Albert Imre. (b. 16 Sept. 1893, Budapest, Hungary; d. 22 Oct. 1986, Woods Hole, MA) biochemistry, cell metabolism [or bioenergetics]. Albert Szent-Györgyi (pronounced like "Saint Georgie") earned recognition for his biochemical work on vitamin C, muscle and energy in the cell. His contributions ranged from the practical, such as finding an inexpensive source of vitamin C and a method for preserving fresh muscle tissue, or designing a continuous centrifuge, to the deeply theoretical, such as conceiving cell function, cancer and the origin of life through electron flow. By portraying the wonder of science and its discoveries, he was widely inspirational, both professionally and publicly. He championed a view of intuitive discovery and scientific play, coupling the grand and the simple, and was outspoken that research funds should be unrestricted. He also gained renown for his charm, nonconformism and anti-war politics. Formative Years and Early Career Albert was born into modest privilege. His father, however, took little notice of the family. Albert was raised primarily by his mother in Budapest. Her brother, an established physiologist, was a frequent presence and, periodically, an austere surrogate father. Until age sixteen, Albert showed neither interest nor aptitude in academics. In the summers he enjoyed horseback riding and hunting. Szent-Györgyi felt inferior as a teenager and defensively tried to prove himself. He also developed a jealous dislike of his two brothers. At age sixteen Albert became motivated, however, apparently by the respect accorded to three generations of scientists in his mother's family, the Lenhosséks. -

Laureatai Pagal Atradimų Sritis

1 Nobelio premijų laureatai pagal atradimų sritis Toliau šioje knygoje Nobelio fiziologijos ir medicinos premijos laureatai suskirstyti pagal jų atradimus tam tikrose fiziologijos ir medicinos srityse. Vienas laureatas gali būti įrašytas keliose srityse. Akies fiziologija 1911 m. Švedų oftalmologas Allvar Gullstrand – už akies lęšiuko laužiamosios gebos tyrimus. 1967 m. Suomių ir švedų neurofiziologas Ragnar Arthur Granit, amerikiečių fiziologai Haldan Keffer Hartline ir George Wald – už akyse vykstančių pirminių fiziologinių ir cheminių procesų atradimą. Antibakteriniai vaistai 1945 m. Škotų mikrobiologas seras Alexander Fleming, anglų biochemikas Ernst Boris Chain ir australų fiziologas seras Howard Walter Florey – už penicilino atradimą ir jo veiksmingumo gydant įvairias infekcijas tyrimus. 1952 m. Amerikiečių mikrobiologas Selman Abraham Waksman – už streptomicino, pirmojo efektyvaus antibiotiko nuo tuberkuliozės, sukūrimą. Audiologija 1961 m. Vengrų biofizikas Georg von Békésy – už sraigės fizinio dirginimo mechanizmo atradimą. Bakteriologija 1901 m. Vokiečių fiziologas Emil Adolf von Behring – už serumų terapijos darbus, ypač pritaikius juos difterijai gydyti (difterijos antitoksino sukūrimą). 1905 m. Vokiečių bakteriologas Heinrich Hermann Robert Koch – už tuberkuliozės tyrimus ir atradimus. 1928 m. Prancūzų bakteriologas Charles Jules Henri Nicolle – už šiltinės tyrimus. 1939 m. Vokiečių bakteriologas Gerhard Johannes Paul Domagk – už prontozilio antibakterinio veikimo atradimą. 1945 m. Škotų mikrobiologas Alexander Fleming, anglų biochemikas Ernst Boris Chain ir australų fiziologas Howard Walter Florey – už penicilino atradimą ir jo veiksmingumo gydant įvairias infekcijas tyrimus. 1952 m. Amerikiečių mikrobiologas Selman Abraham Waksman – už streptomicino, pirmojo efektyvaus antibiotiko nuo tuberkuliozės, sukūrimą. 2005 m. 2 Australų mikrobiologas Barry James Marshall ir australų patologas John Robin Warren – už bakterijos Helicobacter pylori atradimą ir jos įtakos skrandžio ir dvylikapirštės žarnos opos atsivėrimui nustatymą. -

100 Years of Vitamins PETER ENGEL DSM Nutritional Products Europe Ltd

100 years of vitamins PETER ENGEL DSM Nutritional Products Europe Ltd. Member of AgroFOOD industry hi-tech's Scientific Advisory Board Peter Engel Vitamins are important! You probably remember your mother’s orders: Don’t forget to take your vitamins! We’ve all heard similar things but we seldom ask ourselves: What exactly are vitamins and why are they so important? Vitamins are essential organic compounds that the body cannot produce itself and must therefore be obtained through dietary means (exceptions: niacin and vitamin D). There are a total of 13 vitamins vital for many bodily functions, such as the formation of cells and bones and the strengthening of the immune system. Vitamins are designated both by their chemical structure and a letter in combination with a number. Alphabetical gaps have arisen because not all the substances which were originally identifi ed turned out to be single vitamins. Vitamins were discovered at the beginning of the 20th century. At that time, European rice hulling machines were brought to Asia to process rice. However, the hulling process stripped the rice of its vital nutritional elements. As a consequence, new health problems began emerging in the people and animals who relied upon the rice as a staple food. Typically, the symptoms included lower energy levels and signs of paralysis. This dietary defi ciency disease is known as beriberi. For a long time it was thought that food poisoning and infections were the causes of defi ciency diseases like beriberi. Inspired after reading an article on the illness, the Polish biochemist Casimir Funk set about discovering a suitable cure. -

List of Nobel Laureates 1

List of Nobel laureates 1 List of Nobel laureates The Nobel Prizes (Swedish: Nobelpriset, Norwegian: Nobelprisen) are awarded annually by the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences, the Swedish Academy, the Karolinska Institute, and the Norwegian Nobel Committee to individuals and organizations who make outstanding contributions in the fields of chemistry, physics, literature, peace, and physiology or medicine.[1] They were established by the 1895 will of Alfred Nobel, which dictates that the awards should be administered by the Nobel Foundation. Another prize, the Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences, was established in 1968 by the Sveriges Riksbank, the central bank of Sweden, for contributors to the field of economics.[2] Each prize is awarded by a separate committee; the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences awards the Prizes in Physics, Chemistry, and Economics, the Karolinska Institute awards the Prize in Physiology or Medicine, and the Norwegian Nobel Committee awards the Prize in Peace.[3] Each recipient receives a medal, a diploma and a monetary award that has varied throughout the years.[2] In 1901, the recipients of the first Nobel Prizes were given 150,782 SEK, which is equal to 7,731,004 SEK in December 2007. In 2008, the winners were awarded a prize amount of 10,000,000 SEK.[4] The awards are presented in Stockholm in an annual ceremony on December 10, the anniversary of Nobel's death.[5] As of 2011, 826 individuals and 20 organizations have been awarded a Nobel Prize, including 69 winners of the Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences.[6] Four Nobel laureates were not permitted by their governments to accept the Nobel Prize.