Sir Fredrick Gowland Hopkins: the Father of Biochemistry

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Intimations Surnames

Intimations Extracted from the Watt Library index of family history notices as published in Inverclyde newspapers between 1800 and 1918. Surnames H-K This index is provided to researchers as a reference resource to aid the searching of these historic publications which can be consulted on microfiche, preferably by prior appointment, at the Watt Library, 9 Union Street, Greenock. Records are indexed by type: birth, death and marriage, then by surname, year in chronological order. Marriage records are listed by the surnames (in alphabetical order), of the spouses and the year. The copyright in this index is owned by Inverclyde Libraries, Museums and Archives to whom application should be made if you wish to use the index for any commercial purpose. It is made available for non- commercial use under the Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-ShareAlike International License (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 License). This document is also available in Open Document Format. Surnames H-K Record Surname When First Name Entry Type Marriage HAASE / LEGRING 1858 Frederick Auguste Haase, chief steward SS Bremen, to Ottile Wilhelmina Louise Amelia Legring, daughter of Reverend Charles Legring, Bremen, at Greenock on 24th May 1858 by Reverend J. Nelson. (Greenock Advertiser 25.5.1858) Marriage HAASE / OHLMS 1894 William Ohlms, hairdresser, 7 West Blackhall Street, to Emma, 4th daughter of August Haase, Herrnhut, Saxony, at Glengarden, Greenock on 6th June 1894 .(Greenock Telegraph 7.6.1894) Death HACKETT 1904 Arthur Arthur Hackett, shipyard worker, husband of Mary Jane, died at Greenock Infirmary in June 1904. (Greenock Telegraph 13.6.1904) Death HACKING 1878 Samuel Samuel Craig, son of John Hacking, died at 9 Mill Street, Greenock on 9th January 1878. -

JM Coetzee and Mathematics Peter Johnston

1 'Presences of the Infinite': J. M. Coetzee and Mathematics Peter Johnston PhD Royal Holloway University of London 2 Declaration of Authorship I, Peter Johnston, hereby declare that this thesis and the work presented in it is entirely my own. Where I have consulted the work of others, this is always clearly stated. Signed: Dated: 3 Abstract This thesis articulates the resonances between J. M. Coetzee's lifelong engagement with mathematics and his practice as a novelist, critic, and poet. Though the critical discourse surrounding Coetzee's literary work continues to flourish, and though the basic details of his background in mathematics are now widely acknowledged, his inheritance from that background has not yet been the subject of a comprehensive and mathematically- literate account. In providing such an account, I propose that these two strands of his intellectual trajectory not only developed in parallel, but together engendered several of the characteristic qualities of his finest work. The structure of the thesis is essentially thematic, but is also broadly chronological. Chapter 1 focuses on Coetzee's poetry, charting the increasing involvement of mathematical concepts and methods in his practice and poetics between 1958 and 1979. Chapter 2 situates his master's thesis alongside archival materials from the early stages of his academic career, and thus traces the development of his philosophical interest in the migration of quantificatory metaphors into other conceptual domains. Concentrating on his doctoral thesis and a series of contemporaneous reviews, essays, and lecture notes, Chapter 3 details the calculated ambivalence with which he therein articulates, adopts, and challenges various statistical methods designed to disclose objective truth. -

書 名 等 発行年 出版社 受賞年 備考 N1 Ueber Das Zustandekommen Der

書 名 等 発行年 出版社 受賞年 備考 Ueber das Zustandekommen der Diphtherie-immunitat und der Tetanus-Immunitat bei thieren / Emil Adolf N1 1890 Georg thieme 1901 von Behring N2 Diphtherie und tetanus immunitaet / Emil Adolf von Behring und Kitasato 19-- [Akitomo Matsuki] 1901 Malarial fever its cause, prevention and treatment containing full details for the use of travellers, University press of N3 1902 1902 sportsmen, soldiers, and residents in malarious places / by Ronald Ross liverpool Ueber die Anwendung von concentrirten chemischen Lichtstrahlen in der Medicin / von Prof. Dr. Niels N4 1899 F.C.W.Vogel 1903 Ryberg Finsen Mit 4 Abbildungen und 2 Tafeln Twenty-five years of objective study of the higher nervous activity (behaviour) of animals / Ivan N5 Petrovitch Pavlov ; translated and edited by W. Horsley Gantt ; with the collaboration of G. Volborth ; and c1928 International Publishing 1904 an introduction by Walter B. Cannon Conditioned reflexes : an investigation of the physiological activity of the cerebral cortex / by Ivan Oxford University N6 1927 1904 Petrovitch Pavlov ; translated and edited by G.V. Anrep Press N7 Die Ätiologie und die Bekämpfung der Tuberkulose / Robert Koch ; eingeleitet von M. Kirchner 1912 J.A.Barth 1905 N8 Neue Darstellung vom histologischen Bau des Centralnervensystems / von Santiago Ramón y Cajal 1893 Veit 1906 Traité des fiévres palustres : avec la description des microbes du paludisme / par Charles Louis Alphonse N9 1884 Octave Doin 1907 Laveran N10 Embryologie des Scorpions / von Ilya Ilyich Mechnikov 1870 Wilhelm Engelmann 1908 Immunität bei Infektionskrankheiten / Ilya Ilyich Mechnikov ; einzig autorisierte übersetzung von Julius N11 1902 Gustav Fischer 1908 Meyer Die experimentelle Chemotherapie der Spirillosen : Syphilis, Rückfallfieber, Hühnerspirillose, Frambösie / N12 1910 J.Springer 1908 von Paul Ehrlich und S. -

Biography: Sir Benjamin Thompson, Count Rumford

Biography: Christiaan Eijkman As a debilitating and, sometimes, fatal disease spread across the West Indies in the late nineteenth century, one man was devoting all his efforts to finding a cure for it. This man was Christiaan Eijkman, and the disease was beriberi. Through careful experimentation, including a massive study of over two-hundred-and-eighty thou- sand prisoners in Javanese prisons, Eijkman managed to find the cure. Using the findings of Eijkman’s study, scientists were able to isolate a nutrient called thiamin, also known as vitamin B1. Eijkman had, through his research, formed the basis for understanding the role of vitamins in nutrition, for which he received the Nobel Prize, together with Sir Frederick Hopkins, late in his life. Christiaan Eijkman was born on August 11, 1858 muscle weakness. Patients suffering from beriberi in the small town of Nijkerk, in The Netherlands. He commonly lose their sense of feeling and control of was the seventh child of Christiaan Eijkman and their limbs, often leading to paralysis. In some cases, Johanna Alida Pool. Christiaan’s father worked as a fluid collects in the legs, taxing the circulatory system, headmaster at the local school. enlarging the heart, and causing heart failure. The When he was only a few years old, his family relo- disease can be fatal. cated to Zaandam, a larger city in the Netherlands. In Beriberi was increasingly becoming a national se- Zaandam, he began his education at his father’s curity issue for the Netherlands. The mounting inci- school. He progressed in his studies with ease and dence of the disease among the soldiers and sailors passed his university-entrance exams in 1875, at the had already resulted in the Dutch government having age of 17. -

Warburg Effect(S)—A Biographical Sketch of Otto Warburg and His Impacts on Tumor Metabolism Angela M

Otto Cancer & Metabolism (2016) 4:5 DOI 10.1186/s40170-016-0145-9 REVIEW Open Access Warburg effect(s)—a biographical sketch of Otto Warburg and his impacts on tumor metabolism Angela M. Otto Abstract Virtually everyone working in cancer research is familiar with the “Warburg effect”, i.e., anaerobic glycolysis in the presence of oxygen in tumor cells. However, few people nowadays are aware of what lead Otto Warburg to the discovery of this observation and how his other scientific contributions are seminal to our present knowledge of metabolic and energetic processes in cells. Since science is a human endeavor, and a scientist is imbedded in a network of social and academic contacts, it is worth taking a glimpse into the biography of Otto Warburg to illustrate some of these influences and the historical landmarks in his life. His creative and innovative thinking and his experimental virtuosity set the framework for his scientific achievements, which were pioneering not only for cancer research. Here, I shall allude to the prestigious family background in imperial Germany; his relationships to Einstein, Meyerhof, Krebs, and other Nobel and notable scientists; his innovative technical developments and their applications in the advancement of biomedical sciences, including the manometer, tissue slicing, and cell cultivation. The latter were experimental prerequisites for the first metabolic measurements with tumor cells in the 1920s. In the 1930s–1940s, he improved spectrophotometry for chemical analysis and developed the optical tests for measuring activities of glycolytic enzymes. Warburg’s reputation brought him invitations to the USA and contacts with the Rockefeller Foundation; he received the Nobel Prize in 1931. -

Doctorat Honoris Causa

DOCTORAT HONORIS CAUSA Acord núm. 204/2007 del Consell de Govern, pel qual s’aprova la concessió del doctorat Honoris Causa al Professor Sir Michael Atiyah. Document aprovat per la Comissió Permanent del dia 3/12/2007. Document aprovat pel Consell de Govern del dia 17/12/2007. DOCUMENT CG 14/12 2007 Secretaria General Desembre de 2007 PROPOSTA D’ACORD DEL CONSELL DE GOVERN PER A CONCEDIR EL DOCTORAT HONORIS CAUSA PER LA UNIVERSITAT POLITÈCNICA DE CATALUNYA, AL PROFESSOR SIR MICHAEL ATIYAH ANTECEDENTS: 1. El professor Sir Michael Atiyah ha estat guardonat, entre d’altres distincions, amb la Medalla Fields (1966), atorgada per la Unió Matemàtica Internacional, i el Premi Abel (2004), atorgat per l’Acadèmia de Ciències de Noruega, ambdues reconegudes com un Premi Nobel de les Matemàtiques. També ha estat un dels impulsors més decisius de la Societat Matemàtica Europea. 2. En relació amb Catalunya i Barcelona, i més concretament, amb la UPC, el professor Sir Michael Atiyah ha estat president del Comitè Científic del 3r Congrés Europeu de Matemàtiques celebrat a Barcelona l’any 2000. 3. El prestigi internacional del professor Sir Michael Atiyah el fa un candidat idoni com a primer doctor honoris causa per la UPC en un àrea en la qual la nostra Universitat compta amb una comunitat nombrosa i amb un gran prestigi i reconeixement internacionals. 4. El rector ha rebut una proposta formal per a investir el professor Sir Michael Atiyah com a doctor honoris causa per la Universitat Politècnica de Catalunya, signada pel degà de la Facultat de Matemàtiques i Estadística, el director del departament de Matemàtica Aplicada I, el director del departament de Matemàtica Aplicada II, el director del departament de Matemàtica Aplicada III, el director del departament de Matemàtica Aplicada IV, i el director del departament d’Estadística i Investigació Operativa. -

Cambridge's 92 Nobel Prize Winners Part 2 - 1951 to 1974: from Crick and Watson to Dorothy Hodgkin

Cambridge's 92 Nobel Prize winners part 2 - 1951 to 1974: from Crick and Watson to Dorothy Hodgkin By Cambridge News | Posted: January 18, 2016 By Adam Care The News has been rounding up all of Cambridge's 92 Nobel Laureates, celebrating over 100 years of scientific and social innovation. ADVERTISING In this installment we move from 1951 to 1974, a period which saw a host of dramatic breakthroughs, in biology, atomic science, the discovery of pulsars and theories of global trade. It's also a period which saw The Eagle pub come to national prominence and the appearance of the first female name in Cambridge University's long Nobel history. The Gender Pay Gap Sale! Shop Online to get 13.9% off From 8 - 11 March, get 13.9% off 1,000s of items, it highlights the pay gap between men & women in the UK. Shop the Gender Pay Gap Sale – now. Promoted by Oxfam 1. 1951 Ernest Walton, Trinity College: Nobel Prize in Physics, for using accelerated particles to study atomic nuclei 2. 1951 John Cockcroft, St John's / Churchill Colleges: Nobel Prize in Physics, for using accelerated particles to study atomic nuclei Walton and Cockcroft shared the 1951 physics prize after they famously 'split the atom' in Cambridge 1932, ushering in the nuclear age with their particle accelerator, the Cockcroft-Walton generator. In later years Walton returned to his native Ireland, as a fellow of Trinity College Dublin, while in 1951 Cockcroft became the first master of Churchill College, where he died 16 years later. 3. 1952 Archer Martin, Peterhouse: Nobel Prize in Chemistry, for developing partition chromatography 4. -

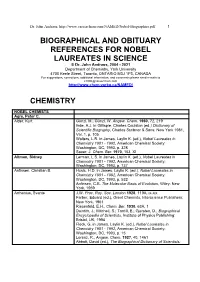

Biographical References for Nobel Laureates

Dr. John Andraos, http://www.careerchem.com/NAMED/Nobel-Biographies.pdf 1 BIOGRAPHICAL AND OBITUARY REFERENCES FOR NOBEL LAUREATES IN SCIENCE © Dr. John Andraos, 2004 - 2021 Department of Chemistry, York University 4700 Keele Street, Toronto, ONTARIO M3J 1P3, CANADA For suggestions, corrections, additional information, and comments please send e-mails to [email protected] http://www.chem.yorku.ca/NAMED/ CHEMISTRY NOBEL CHEMISTS Agre, Peter C. Alder, Kurt Günzl, M.; Günzl, W. Angew. Chem. 1960, 72, 219 Ihde, A.J. in Gillispie, Charles Coulston (ed.) Dictionary of Scientific Biography, Charles Scribner & Sons: New York 1981, Vol. 1, p. 105 Walters, L.R. in James, Laylin K. (ed.), Nobel Laureates in Chemistry 1901 - 1992, American Chemical Society: Washington, DC, 1993, p. 328 Sauer, J. Chem. Ber. 1970, 103, XI Altman, Sidney Lerman, L.S. in James, Laylin K. (ed.), Nobel Laureates in Chemistry 1901 - 1992, American Chemical Society: Washington, DC, 1993, p. 737 Anfinsen, Christian B. Husic, H.D. in James, Laylin K. (ed.), Nobel Laureates in Chemistry 1901 - 1992, American Chemical Society: Washington, DC, 1993, p. 532 Anfinsen, C.B. The Molecular Basis of Evolution, Wiley: New York, 1959 Arrhenius, Svante J.W. Proc. Roy. Soc. London 1928, 119A, ix-xix Farber, Eduard (ed.), Great Chemists, Interscience Publishers: New York, 1961 Riesenfeld, E.H., Chem. Ber. 1930, 63A, 1 Daintith, J.; Mitchell, S.; Tootill, E.; Gjersten, D., Biographical Encyclopedia of Scientists, Institute of Physics Publishing: Bristol, UK, 1994 Fleck, G. in James, Laylin K. (ed.), Nobel Laureates in Chemistry 1901 - 1992, American Chemical Society: Washington, DC, 1993, p. 15 Lorenz, R., Angew. -

Holding Hands with Bacteria the Life and Work of Marjory Stephenson

SPRINGER BRIEFS IN MOLECULAR SCIENCE HISTORY OF CHEMISTRY Soňa Štrbáňová Holding Hands with Bacteria The Life and Work of Marjory Stephenson 123 SpringerBriefs in Molecular Science History of Chemistry Series editor Seth C. Rasmussen, Fargo, North Dakota, USA More information about this series at http://www.springer.com/series/10127 Soňa Štrbáňová Holding Hands with Bacteria The Life and Work of Marjory Stephenson 1 3 Soňa Štrbáňová Academy of Sciences of the Czech Republic Prague Czech Republic ISSN 2191-5407 ISSN 2191-5415 (electronic) SpringerBriefs in Molecular Science ISSN 2212-991X SpringerBriefs in History of Chemistry ISBN 978-3-662-49734-0 ISBN 978-3-662-49736-4 (eBook) DOI 10.1007/978-3-662-49736-4 Library of Congress Control Number: 2016934952 © The Author(s) 2016 This work is subject to copyright. All rights are reserved by the Publisher, whether the whole or part of the material is concerned, specifically the rights of translation, reprinting, reuse of illustrations, recitation, broadcasting, reproduction on microfilms or in any other physical way, and transmission or information storage and retrieval, electronic adaptation, computer software, or by similar or dissimilar methodology now known or hereafter developed. The use of general descriptive names, registered names, trademarks, service marks, etc. in this publication does not imply, even in the absence of a specific statement, that such names are exempt from the relevant protective laws and regulations and therefore free for general use. The publisher, the authors and the editors are safe to assume that the advice and information in this book are believed to be true and accurate at the date of publication. -

Studies on the in Vitro Digestion of Cellulose By

STUDIES ON THE IN VITRO DIGESTION OF CELLULOSE BY RUIvIEN MICROORGANISMS By ROBERT LAWRENCE SALSBURY A THESIS Submitted to the School of Graduate Studies of Michigan State College of Agriculture and Applied Science in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Department of Dairy 1955 ProQuest Number: 10008419 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 10008419 Published by ProQuest LLC (2016). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106- 1346 STUDIES ON THE IN VITRO DIGESTION OF CELLULOSE BY RUMEN MICROORGANISMS By ROBERT LAURENCE SALSBURY rjmiirr AN ABSTRACT Submitted to the School of Graduate Studies of Michigan State College of Agriculture and Applied Science in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Department of Dairy Year 1955 Approved 1 Four methods of incubating rumen fluid for the purpose of studying cellulose digestion in vitro were examined. Under the conditions used, it was found that the maximum cellulose digestion and most reproducible results were obtained when a semipermeable sac was used and the inoculum: mineral-solution ratio was small. -

The Making of a Biochemist

book reviews disappearance of kuru as an important In the late 1920s, he looked into the effect TION episode in our understanding of the risks of light on the inhibition by carbon monox- A associated with this type of infectious ide of respiration in living cells. This work process. Informing the wider community of encompassed considerations of photo- these risks may lead to a more helpful debate chemical processes in terms of quantum about the public health policies required chemistry, and the use of the manometer, NOBEL FOUND to minimize the chances of another BSE photoelectric cell and spectroscope. From epidemic. Books such as this are useful in the shape of the curve obtained by plotting this context. the effectiveness of light against its wave- Colin L. Masters is in the Department of Pathology, length, it was possible to deduce the resem- 8 The University of Melbourne, Parkville, Victoria, blance between the respiratory ferment and 3052, Australia. haemins. Warburg was awarded the Nobel prize for physiology or medicine in 1931 for his recognition of the haemin-type nature of the respiratory ferment and its underlying The making principles. The development of Warburg’s theoreti- of a biochemist cal thinking and experimental procedures are Otto Warburgs Beitrag zur ably chronicled in Petra Werner’s introducto- Atmungstheorie: Das Problem der ry essay. Her book is the first volume of an Sauerstoffaktivierung* edition of Warburg’s correspondence Brilliant but flawed: Warburg tended to pettiness. by Petra Werner deposited in the Berlin–Brandenburg Aca- Basilisken-Presse: 1996. Pp. 390. DM136 demy of Sciences. Regrettably, the 143 pub- 1950). -

The Fessard's School of Neurophysiology After

The fessard’s School of neurophysiology after the Second World War in france: globalisation and diversity in neurophysiological research (1938-1955) Jean-Gaël Barbara To cite this version: Jean-Gaël Barbara. The fessard’s School of neurophysiology after the Second World War in france: globalisation and diversity in neurophysiological research (1938-1955). Archives Italiennes de Biologie, Universita degli Studi di Pisa, 2011. halshs-03090650 HAL Id: halshs-03090650 https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-03090650 Submitted on 11 Jan 2021 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. The Fessard’s School of neurophysiology after the Second World War in France: globalization and diversity in neurophysiological research (1938-1955) Jean- Gaël Barbara Université Pierre et Marie Curie, Paris, Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique, CNRS UMR 7102 Université Denis Diderot, Paris, Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique, CNRS UMR 7219 [email protected] Postal Address : JG Barbara, UPMC, case 14, 7 quai Saint Bernard, 75005,