(Icts) in Shaping Identity Threats and Responses Mary Macharia University of Arkansas, Fayetteville

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

October 24, 2013

JOB HUNTING? ALL THE LATEST The Breeze is looking for Download our mobile app copy and news editors. for news on the go at Apply at joblink.jmu.edu. breezejmu.org. Serving James Madison University Since 1922 Partly Cloudy n 52°/ 31° Vol. 92, No. 18 chance of precipitation: 10% Thursday, October 24, 2013 Dukes Teaching the craft ready for Political science professor designs virtual strategy game to teach students second leg of season Football rested after bye week, face William & Mary Saturday By CONNOR DREW The Breeze Students. Teachers. Athletes. Coaches … Reporters. Who doesn’t love a week off from working? While they may not have been sitting on their couches all day, the Dukes (5-2, 2-1 Colonial Athletic Association) are rested and ready BRIAN PRESCOTT / THE BREEZE to get back into the the thick of the Students in Jonathan Keller’s foreign affairs class discuss political strategies for their simulated counties in Keller’s foreign policy game, Statecraft. season after their bye week. “We took advantage of the bye week,” Head coach Mickey Matthews By MARY KATE WHITE improve simulated citizens’ quality of life. said. “We were beat up even before The Breeze In the game’s analog days, Keller spent hours every week calculat- the Richmond game. We needed a ing his students’ countries’ resources, growth and approval ratings. week off. We practiced in our sweats Students looking to take over the world will finally have He was eventually inspired to simulate Statecraft by strategy games all week — we did not hit … We’re as their chance, thanks to one professor’s interactive program of like Civilization and Warcraft. -

PERSONALITY Personality Not Included

Early Praise for Personality Not Included “Wow. I devoured Personality Not Included, frequently shouting ‘yes!’ as I followed Rohit’s spot-on analysis of a fundamental truth: being faceless doesn’t work anymore. Per- sonality in both people and companies is what customers get passionate about and drives seemingly unlimited success. This is one of those rare books to purchase by the case so you can give copies to employees and investors. But make sure to keep a few for yourself to read and reread so you don’t miss a thing. Bravo!” —David Meerman Scott, bestselling author of The New Rules of Marketing and PR “Personality Not Included breaks down the old barriers between marketing, advertis- ing, and PR and shows people how to nail the single objective of it all: creating pow- erful conversations with your customers and getting them to choose you over the rest.” —Timothy Ferriss, top blogger and #1 New York Times bestselling author of The 4-Hour Workweek “There are two types of small business owners—ones who know they are in the busi- ness of marketing and those who don’t. For either, Personality Not Included is an eye- opening look at what really matters when it comes to delighting your customers. If you want a guide to being more than ordinary, get this book.” —John Jantsch, award-winning blogger and author of Duct Tape Marketing “Just being pretty isn’t enough anymore, today a brand also needs a strong personal- ity to survive. In PNI, Rohit gives you the techniques and tools to help your brand go from wallflower to social butterfly.” —Laura Ries, bestselling author of 22 Immutable Laws of Branding, and cofounder of Ries & Ries “Finally. -

MELT © Heidi Wicks (Thesis)

MELT © Heidi Wicks (Thesis) submitted to the School of Graduate Studies in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts (Creative Writing) Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences Memorial University of Newfoundland May 2019 St. John’s Newfoundland and Labrador MELT A novel by Heidi Wicks 1 Melt shifts between two girls who come of age together during two economically turbulent times - the late ‘90s and present-day - in St. John's, Newfoundland. The women navigate break-ups, tanning beds, spray tans, drifting desires, at least one kid with a raisin up his nose, drunken dancing, infidelity, death, sex in Middle Cove, job loss at the CBC and love loss at the Avalon Mall. Through the pockets of their maddening but beloved city, their friendships and relationships are tested, but their brazen humour and deep- rooted friendship helps them ice-pick through the winter sludge and spring muck and get them through until it’s summer once more. 2 Chapter One “About here?” Cait slices her index finger across the middle of her right thigh, softly. A knife etching a line in butter. “Your father’s not lettin’ you get away with a slit that high.” Tilley Brophy plucks the cigarette from her lips and releases a poof of smoke that curls into the shape of an anchor. She jabs the butt into a heavy crystal ashtray and coughs like her freakin’ lungs are about to vault from her body and splat against her half-brown-carpet, half-brown- wood-panel wall in her house by the Village Mall. -

National Practices Survey Report 2017

National Practices Survey Report 2017 A survey of residential service providers for victims of domestic human trafficking Jeanne L. Allert, Editor The Samaritan Women Express permission from The Samaritan Women is required prior to reproduction or distribution of any part of this report. For more information contact: Jeanne L. Allert [email protected] © The Samaritan Women Institute for Shelter Care Section A. Background In 2016, our organization, The Samaritan Women, was gifted with the funds to host a national conference for service providers that offer residential care to victims of domestic sex trafficking. The gathering was held over a four-day period at Wheaton College in Chicago, Illinois in July of that year. Twenty-two agencies were present, and a host of individuals who aspired to get involved in survivor care. From that event, three observations emerged: 1. The majority of those in attendance were the founders of their organizations, many of whom left other occupations to pursue what they felt to be a calling on their lives. All of us had weathered long seasons of feeling alone, crazy, full of doubt, despair, and isolation...and yet we pressed on. It was poignantly clear that this group of pioneers needed the collegiality of this unique gathering. 2. Many of us were having similar experiences and making comparable decisions, but had no baseline against which to measure if we were doing things correctly. To this day there remains no credible, authoritative entity offering guidance (or dare we say, “best practices”) for how this work should be done. 3. The other group of people who attended the 2016 conference were those who were in some stage of envisioning a similar work, or having trouble getting started. -

Comment Submitted by David Crawley Comment View Document

Comment Submitted by David Crawley Comment View document: The notion that my social media identifier should have anything to do with entering the country is a shockingly Nazi like rule. The only thing that this could facilitate anyway is trial by association - something that is known to ensnare innocent people, and not work. What is more this type of thing is repugnant to a free society. The fact that it is optional doesn't help - as we know that this "optional" thing will soon become not-optional. If your intent was to keep it optional - why even bother? Most importantly the rules that we adopt will tend to get adopted by other countries and frankly I don't trust China, India, Turkey or even France all countries that I regularly travel to from the US with this information. We instead should be a beacon for freedom - and we fail in our duty when we try this sort of thing. Asking for social media identifier should not be allowed here or anywhere. Comment Submitted by David Cain Comment View document: I am firmly OPPOSED to the inclusion of a request - even a voluntary one - for social media profiles on the I-94 form. The government should NOT be allowed to dip into users' social media activity, absent probable cause to suspect a crime has been committed. Bad actors are not likely to honor the request. Honest citizens are likely to fill it in out of inertia. This means that the pool of data that is built and retained will serve as a fishing pond for a government looking to control and exploit regular citizens. -

67453 O4 Proposal Opening: May 15, 2015

For public information purposes only; not part of contract. Request for Proposal Number 4958 Z1 Contract Number 67453 O4 Proposal Opening: May 15, 2015 In accordance with Nebraska Revised Statutes §84.712.05(3), the following material(s) has no t been included due to it being marked proprietary. Firespring 1. None In accordan ce with Fed eral U.S. Copyright Law Title 17 U.S.C. Section 101 et seq., Title 1 8 U.S.C. 2319, the following material(s) has not been included due to them being copyrighted. Firespring 1. None May IS, 2015 Dear Selection Committee, Thank you for allowing us to present our capabilities and qualifications for your consideration. It is our privilege to supply you with the enclosed information in response to your request for proposal. We are e)(cited about the opportunity to help your organization increase statewide education on and pubUc awa reness of th e need for organ and tissue donation. Snitily Carr has taken on similar educational and awareness challenges before and has a proven tfack record in helping public health organizations accomplish their campaign goals. We approach these challenges seriously and strategically. To us, it's much more than a campaign-it is a mission. Ultimatel y, it is about people's lives and the well-being of Nebraska families. And to be successful, it requires much more than a client-vendor relat ionship-it requires a strategic partnership. That collaborative approach combined with our e)(perience, resources, and passion for the cause makes us ideally suited to be your communications partner. -

World Mission Report 2016 Missionaries–Shepherds Conference World Missionworld Special Report University Bible Fellowship 2016 University 2016 Bible Fellowship

“HE SAID TO THEM, ‘GO INTO ALL THE WORLD AND PREACH THE GOOD NEWS TO ALL CREATION.’” MARK 16:15 WORLD MISSION REPORT 2016 MISSIONARIES–SHEPHERDS CONFERENCE SPECIAL WORLD MISSIONWORLD REPORT UNIVERSITY BIBLE FELLOWSHIP 2016 UNIVERSITY 2016 BIBLE FELLOWSHIP SPECIAL ISSUE — WORLD MISSION REPORT 2016 1 WORLD MISSION REPORT 2016 MESSAGE UBF Newsletter BY DR. ABRAHAM KIM, GENERAL DIRECTOR WORLD MISSION REPORT 2016 A HOLY NATION 3 MESSAGE BY DR. ABRAHAM KIM, GENERAL DIRECTOR 7 REPORT BY DAVID KIM, KOREA UBF DIRECTOR 8 LIFE TESTIMONY BY STEVEN SEBBALE, MAKERERE UBF, UGANDA Exodus 19:4–6 10 LIFE TESTIMONY BY AUGUSTINE ZHDANOV, KIEV UBF, UKRAINE Key Verse: 19:5–6a 12 LIFE TESTIMONY BY GUSTAVO PRATO, CARACAS UBF, VENEZUELA “Now if you obey me fully and keep my covenant, then out of all nations you will be my treasured possession. Although the whole earth is mine, you will be for me a kingdom of priests and a holy 14 LIFE TESTIMONY BY BOB HENKINS, IIT UBF, USA nation.” 16 LIFE TESTIMONY BY ALLISON HAGA, KAOHSIUNG UBF, TAIWAN thank and praise God who has used UBF for world campus ever, they became slaves and suffered. Though they ate steak MISSIONARIES–SHEPHERDS CONFERENCE missions and blessed us for the past 55 years. I thank God and pork chops beside cooking pots, their joy lasted for just a for all missionaries, native leaders, Korean shepherds and moment. God had heard them crying in misery and came down 19 OPENING MESSAGE BY RON WARD, CHICAGO UBF, USA brothers and sisters who have dedicated their lives to God’s to rescue them (Ex 3:7–8). -

On the Same Page an Analysis of the Mommy Blogging Phenomenon

On the same page An analysis of the mommy blogging phenomenon Senni Karvonen Master’s thesis English Philology Faculty of Humanities University of Oulu Spring 2014 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 INTRODUCTION 4 1.1 Research topic and goals 5 1.2 Previous research and sources 8 1.3 Practices and ethics in doing internet research 9 1.4 The organization of the Pro Gradu 11 2 THE MOMMY BLOGGING PHENOMENON 12 2.1 Blogging in a nutshell 12 2.2 Ideology of the good mother 15 2.3 Motherhood online 19 2.3.1 Mommy blogging as a genre 19 2.3.2 The radical act of mommy blogging? 21 2.3.3 A community of the isolated contemporary mothers 24 2.3.4 The monetized mommy 26 3 DATA AND ITS CONTEXT 30 4 APPLYING ASPECTS OF CRITICAL DISCOURSE ANALYSIS TO BLOGS 36 4.1 CDA and its view on discourse, analysis, and critique 38 4.2 How to identify and characterize discourses? 41 5 CASE MARIA KANG AND THE PROTEST BY MOMMY BLOGGERS 43 5.1 What is this protest all about? 43 3 5.2 Themes and discourses 47 5.2.1 Views of maternal roles 48 5.3.2 Views of (female) social behavior 52 5.3.3 Views of health 57 5.3.4 Views of postpartum body image and appearance 65 5.3.5 Summary of discourses 70 5.3 Reinforcing community through sameness and support 73 6 CONCLUSION 79 List of references 84 Appendix 87 4 1 INTRODUCTION What is a mother to do when the writing she wants to read isn’t there? When the only discussion about maternal ambivalence is the one in the glossy magazine about whether to get the Bugaboo or the Frog stroller? [--] Mothers, as we know, are incredibly resourceful. -

Content Experts Reveal for Kids Their Secrets Positive Digital Content for Kids

EDITED BY REMCO PIJPERS & NICOLE VAN Den BOSCH POSITIVE DIGITAL content EXPERTS REVEAL FOR KIDS THEIR SECRETS POSITIVE DIGITAL content FOR KIDS EXP ERTS REVEAL THEIR SECRETS EDITED BY REMCO PIJPERS & NICOLE VAN Den BOSCH POSCON & MIJN KIND ONLIne CHAPTER 3 CHAPTER 5 TABLE OF 56 84 Science & Family Crowdfunding & Coding Het Klokhuis: exploring Science with an App Hello Ruby: Planting the Seed CONTENTS 96 Do-It-Yourself ‘Maker Spaces’ FOREWORD CHAPTER 1 4 26 By neelie Kroes, former Vice-President Testing & Humour of the european commission BB c App: educational and entertaining 40 Laughter & Apps INTRODUCTION 8 Children & Media, Viewpoints from Experts > Sonia Livingstone: Let Kids create and Participate CHAPTER 6 > 98 Patti M. Valkenburg: the teletubbies controversy Co-creating & Characters CHAPTER 4 & the Value of entertainment 5 4 3 2 1 the Playful World of toca Boca 70 Strategy & Innovation the Ravensburger Philosophy: enjoyment, education & togetherness CHAPTER 2 42 Gaming & Education Paxel123: Play & Learn APPENDICES 112 > c hecklist for Positive content for Kids Aged 4-12 > ten Privacy tips for App Developers > About PoSCOn & Mijn Kind online FOREWORD owadays, most of us access online child-abusive material. All of these contribute to content from many different devices, making the Internet a place where children can such as smartphones, tablets and com- have positive experiences. Nputers. Many of us produce online content too. either way, the Internet is a fantastic However, progress in this area is a shared respon- place to learn, play, interact and explore. sibility, and the PoSCOn network – funded by the eU Safer Internet programme – has also been THE My job as european commissioner for the Digi- very active in gathering experts from the public tal Agenda is to ensure that all europeans can and private sector from all over europe in order to benefit from digital technology – including kids, exchange their experiences and devise plans for who are going online at a younger and younger stimulating positive online content for children. -

Lower Rhetoric to Help Ease Tension in Gulf, Says US

BUSINESS | Page 1 SPORT | Page 1 Evergreen Rossi wins DOW JONES QE NYMEX INDEX Saudi to account for QATAR 2, 3, 16 BUSINESS 1-4, 7-8 Dutch INTERNATIONAL 4-13 CLASSIFIED 5-7 21,33900 9,030.44 43.01 two-thirds of $140bn -9.00 +252.71 +0.27 COMMENT 14, 15 SPORTS 1-8 title -0.04% +2.88% +0.63% GCC defi cit in 2017: IIF Latest Figures published in QATAR since 1978 MONDAY Vol. XXXVIII No. 10496 June 26, 2017 Shawwal 2, 1438 AH GULF TIMES www. gulf-times.com 2 Riyals Emir, Father Emir perform Eid prayer, receive well-wishers In brief QATAR | Offi cial Emir exchanges Eid greetings with Rouhani His Highness the Emir Sheikh Tamim bin Hamad al-Thani yesterday exchanged greetings with the President of the Islamic Republic of Iran Dr Hassan Rouhani on the advent of Eid al-Fitr during a phone call the Emir held in the afternoon. QATAR | Offi cial Emir holds phone talk with Pakistani PM His Highness the Emir Sheikh Tamim bin Hamad al-Thani yesterday held a His Highness the Emir Sheikh Tamim telephone conversation with Pakistan’s bin Hamad al-Thani and His Highness Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif to the Father Emir Sheikh Hamad bin congratulate him on the occasion of Khalifa al-Thani perform the Eid al-Fitr advent of the blessed Eid al-Fitr. During His Highness the Emir Sheikh Tamim bin Hamad al-Thani and His Highness the prayer along with citizens at Al Wajbah the phone call, the Emir also expressed Father Emir Sheikh Hamad bin Khalifa al-Thani at the Al Wajbah Palace. -

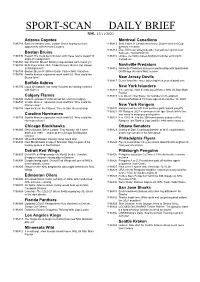

Sport-Scan Daily Brief

SPORT-SCAN DAILY BRIEF NHL 12/11/2020 Arizona Coyotes Montreal Canadiens 1196789 Back for another year, Jordan Gross hoping for more 1196813 Best trades in Canadiens history: Dryden deal set Cup opportunity with Arizona Coyotes dynasty in motion 1196814 Élise Béliveau 'always beside' Canadiens legend Jean Boston Bruins Béliveau, 'not behind him' 1196790 Report: B's could be in division with these teams as part of 1196815 Unique mentality makes Mattias Norlinder enticing to 2020-21 realignment Canadiens 1196791 Doc Emrick: Bruins' Stanley Cup window isn't closed yet 1196792 BHN Puck Links: NHL Trade Rumors, Bruins Get Hosed Nashville Predators In Realignment! 1196816 Nashville Predators announce partnership with sportsbook 1196793 Boston Bruins Hit Billion Dollar Club in NHL Valuation DraftKings ahead of NHL season 1196794 Seattle Kraken eXpansion mock draft 5.0: Who could the Bruins lose? New Jersey Devils 1196817 Devils’ franchise value takes big hit in year of pandemic Buffalo Sabres 1196795 Linus Weissbach 'not really' focused on earning contract New York Islanders with Sabres 1196818 ‘I need help’: How friends saved former NHL All-Star Mark Parrish Calgary Flames 1196819 Life Doesn’t Get Easier for Islanders in Realigned 1196796 Defence prospect Valimaki set for return to Calgary DivisionsPublished 15 hours ago on December 10, 2020 1196797 Seattle Kraken eXpansion mock draft 5.0: Who could the Flames lose? New York Rangers 1196798 How we’d run the Flames: Time to take the neXt step 1196820 Rangers will benefit from perilous path toward playoffs 1196821 NY Rangers 2021 season preview: Igor Shesterkin's time Carolina Hurricanes has come in deep group of goalies 1196799 Seattle Kraken eXpansion mock draft 5.0: Who could the 1196822 It is 2023-24. -

Mayor Gillmor July 2021 Date Time Subject Attendees 7/1

MAYOR GILLMOR AUGUST 2021 DATE TIME SUBJECT ATTENDEES Councilmember Kathy Watanabe; Ruben Torres, Fire Chief, City of Santa 8/1/2021 8:00 AM Bay 2 Brooklyn Launch Clara; Darrell Sales, Retired Firefighter and Event Lead 8/2/2021 5:00 PM US-Bangladesh Tech Investment Summit Councilmember Kathy Watanabe; Public Event Meeting regarding 1200 Memorex; Historical and 8/3/2021 1:00 PM Landmarks Commission Gary Filizetti, President, Devcon Construction 8/3/2021 5:00 PM National Night Out Public Event Glenn Hendricks, Chair, VTA Board of Directors (BOD), Carmen Montano, Phone Meeting regarding Valley Transportation Authority Director, VTA BOD; Manolo Gonzalez-Estay, Government Affairs Policy 8/4/2021 2:00 PM (VTA) Governance Matters Analyst, VTA JW House Grand Opening of New Family Suite at the 8/4/2021 4:00 PM Alderwood Community Room Public Event 8/5/2021 5:30 PM Valley Transportation Authority Board of Directors Meeting Public Meeting Supervisor Susan Ellenberg, Santa Clara County Board of Supervisors, District 8/6/2021 11:00 AM Meeting regarding Local City/County Matters 4 Ribbon Cutting Ceremonies at Abraham Agnew Elementary 8/7/2021 10:30 AM School and Dolores Huerta Middle School Public Event Geoff Brown, President, USA Properties Fund; Steve Gall, Executive Vice President, USA Properties Fund; Tippy Lambert, Vice President, USA Properties Fund; Eric Morley, Principal, The Morley Bros.; Cynthia James, 8/9/2021 1:00 PM Meeting regarding 190 N. Winchester Boulevard Principal, Noble James, LLC 8/9/2021 2:00 PM Introductory Meeting Pastor Chris