Original.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

View Full Article

ARTICLE ADAPTING COPYRIGHT FOR THE MASHUP GENERATION PETER S. MENELL† Growing out of the rap and hip hop genres as well as advances in digital editing tools, music mashups have emerged as a defining genre for post-Napster generations. Yet the uncertain contours of copyright liability as well as prohibitive transaction costs have pushed this genre underground, stunting its development, limiting remix artists’ commercial channels, depriving sampled artists of fair compensation, and further alienating netizens and new artists from the copyright system. In the real world of transaction costs, subjective legal standards, and market power, no solution to the mashup problem will achieve perfection across all dimensions. The appropriate inquiry is whether an allocation mechanism achieves the best overall resolution of the trade-offs among authors’ rights, cumulative creativity, freedom of expression, and overall functioning of the copyright system. By adapting the long-standing cover license for the mashup genre, Congress can support a charismatic new genre while affording fairer compensation to owners of sampled works, engaging the next generations, and channeling disaffected music fans into authorized markets. INTRODUCTION ........................................................................ 443 I. MUSIC MASHUPS ..................................................................... 446 A. A Personal Journey ..................................................................... 447 B. The Mashup Genre .................................................................... -

Tattoos & IP Norms

Case Western Reserve University School of Law Scholarly Commons Faculty Publications 2013 Tattoos & IP Norms Aaron K. Perzanowski Case Western University School of Law, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.law.case.edu/faculty_publications Part of the Intellectual Property Law Commons Repository Citation Perzanowski, Aaron K., "Tattoos & IP Norms" (2013). Faculty Publications. 47. https://scholarlycommons.law.case.edu/faculty_publications/47 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Case Western Reserve University School of Law Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of Case Western Reserve University School of Law Scholarly Commons. Article Tattoos & IP Norms Aaron Perzanowski† Introduction ............................................................................... 512 I. A History of Tattoos .............................................................. 516 A. The Origins of Tattooing ......................................... 516 B. Colonialism & Tattoos in the West ......................... 518 C. The Tattoo Renaissance .......................................... 521 II. Law, Norms & Tattoos ........................................................ 525 A. Formal Legal Protection for Tattoos ...................... 525 B. Client Autonomy ...................................................... 532 C. Reusing Custom Designs ......................................... 539 D. Copying Custom Designs ....................................... -

PERSONALITY Personality Not Included

Early Praise for Personality Not Included “Wow. I devoured Personality Not Included, frequently shouting ‘yes!’ as I followed Rohit’s spot-on analysis of a fundamental truth: being faceless doesn’t work anymore. Per- sonality in both people and companies is what customers get passionate about and drives seemingly unlimited success. This is one of those rare books to purchase by the case so you can give copies to employees and investors. But make sure to keep a few for yourself to read and reread so you don’t miss a thing. Bravo!” —David Meerman Scott, bestselling author of The New Rules of Marketing and PR “Personality Not Included breaks down the old barriers between marketing, advertis- ing, and PR and shows people how to nail the single objective of it all: creating pow- erful conversations with your customers and getting them to choose you over the rest.” —Timothy Ferriss, top blogger and #1 New York Times bestselling author of The 4-Hour Workweek “There are two types of small business owners—ones who know they are in the busi- ness of marketing and those who don’t. For either, Personality Not Included is an eye- opening look at what really matters when it comes to delighting your customers. If you want a guide to being more than ordinary, get this book.” —John Jantsch, award-winning blogger and author of Duct Tape Marketing “Just being pretty isn’t enough anymore, today a brand also needs a strong personal- ity to survive. In PNI, Rohit gives you the techniques and tools to help your brand go from wallflower to social butterfly.” —Laura Ries, bestselling author of 22 Immutable Laws of Branding, and cofounder of Ries & Ries “Finally. -

MELT © Heidi Wicks (Thesis)

MELT © Heidi Wicks (Thesis) submitted to the School of Graduate Studies in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts (Creative Writing) Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences Memorial University of Newfoundland May 2019 St. John’s Newfoundland and Labrador MELT A novel by Heidi Wicks 1 Melt shifts between two girls who come of age together during two economically turbulent times - the late ‘90s and present-day - in St. John's, Newfoundland. The women navigate break-ups, tanning beds, spray tans, drifting desires, at least one kid with a raisin up his nose, drunken dancing, infidelity, death, sex in Middle Cove, job loss at the CBC and love loss at the Avalon Mall. Through the pockets of their maddening but beloved city, their friendships and relationships are tested, but their brazen humour and deep- rooted friendship helps them ice-pick through the winter sludge and spring muck and get them through until it’s summer once more. 2 Chapter One “About here?” Cait slices her index finger across the middle of her right thigh, softly. A knife etching a line in butter. “Your father’s not lettin’ you get away with a slit that high.” Tilley Brophy plucks the cigarette from her lips and releases a poof of smoke that curls into the shape of an anchor. She jabs the butt into a heavy crystal ashtray and coughs like her freakin’ lungs are about to vault from her body and splat against her half-brown-carpet, half-brown- wood-panel wall in her house by the Village Mall. -

National Practices Survey Report 2017

National Practices Survey Report 2017 A survey of residential service providers for victims of domestic human trafficking Jeanne L. Allert, Editor The Samaritan Women Express permission from The Samaritan Women is required prior to reproduction or distribution of any part of this report. For more information contact: Jeanne L. Allert [email protected] © The Samaritan Women Institute for Shelter Care Section A. Background In 2016, our organization, The Samaritan Women, was gifted with the funds to host a national conference for service providers that offer residential care to victims of domestic sex trafficking. The gathering was held over a four-day period at Wheaton College in Chicago, Illinois in July of that year. Twenty-two agencies were present, and a host of individuals who aspired to get involved in survivor care. From that event, three observations emerged: 1. The majority of those in attendance were the founders of their organizations, many of whom left other occupations to pursue what they felt to be a calling on their lives. All of us had weathered long seasons of feeling alone, crazy, full of doubt, despair, and isolation...and yet we pressed on. It was poignantly clear that this group of pioneers needed the collegiality of this unique gathering. 2. Many of us were having similar experiences and making comparable decisions, but had no baseline against which to measure if we were doing things correctly. To this day there remains no credible, authoritative entity offering guidance (or dare we say, “best practices”) for how this work should be done. 3. The other group of people who attended the 2016 conference were those who were in some stage of envisioning a similar work, or having trouble getting started. -

Comment Submitted by David Crawley Comment View Document

Comment Submitted by David Crawley Comment View document: The notion that my social media identifier should have anything to do with entering the country is a shockingly Nazi like rule. The only thing that this could facilitate anyway is trial by association - something that is known to ensnare innocent people, and not work. What is more this type of thing is repugnant to a free society. The fact that it is optional doesn't help - as we know that this "optional" thing will soon become not-optional. If your intent was to keep it optional - why even bother? Most importantly the rules that we adopt will tend to get adopted by other countries and frankly I don't trust China, India, Turkey or even France all countries that I regularly travel to from the US with this information. We instead should be a beacon for freedom - and we fail in our duty when we try this sort of thing. Asking for social media identifier should not be allowed here or anywhere. Comment Submitted by David Cain Comment View document: I am firmly OPPOSED to the inclusion of a request - even a voluntary one - for social media profiles on the I-94 form. The government should NOT be allowed to dip into users' social media activity, absent probable cause to suspect a crime has been committed. Bad actors are not likely to honor the request. Honest citizens are likely to fill it in out of inertia. This means that the pool of data that is built and retained will serve as a fishing pond for a government looking to control and exploit regular citizens. -

67453 O4 Proposal Opening: May 15, 2015

For public information purposes only; not part of contract. Request for Proposal Number 4958 Z1 Contract Number 67453 O4 Proposal Opening: May 15, 2015 In accordance with Nebraska Revised Statutes §84.712.05(3), the following material(s) has no t been included due to it being marked proprietary. Firespring 1. None In accordan ce with Fed eral U.S. Copyright Law Title 17 U.S.C. Section 101 et seq., Title 1 8 U.S.C. 2319, the following material(s) has not been included due to them being copyrighted. Firespring 1. None May IS, 2015 Dear Selection Committee, Thank you for allowing us to present our capabilities and qualifications for your consideration. It is our privilege to supply you with the enclosed information in response to your request for proposal. We are e)(cited about the opportunity to help your organization increase statewide education on and pubUc awa reness of th e need for organ and tissue donation. Snitily Carr has taken on similar educational and awareness challenges before and has a proven tfack record in helping public health organizations accomplish their campaign goals. We approach these challenges seriously and strategically. To us, it's much more than a campaign-it is a mission. Ultimatel y, it is about people's lives and the well-being of Nebraska families. And to be successful, it requires much more than a client-vendor relat ionship-it requires a strategic partnership. That collaborative approach combined with our e)(perience, resources, and passion for the cause makes us ideally suited to be your communications partner. -

Open Steinle Cory Kanyecriticism.Pdf

THE PENNSYLVANIA STATE UNIVERSITY SCHREYER HONORS COLLEGE DEPARTMENT OF COMMUNICATION ARTS & SCIENCES “I THOUGHT ABOUT KILLING YOU”: CONSIDERING THE UTILITY OF RHETORICAL AND BIOGRAPHICAL CRITICAL APPROACHES TO KANYE WEST’S YE CORY N. STEINLE SPRING 2020 A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for baccalaureate degrees in Communication Arts and Sciences and Labor and Employment Relations with honors in Communication Arts and Sciences Reviewed and approved* by the following: Bradford Vivian Professor of Communication Arts & Sciences Thesis Supervisor Lori Bedell Associate Teaching Professor in Communication Arts & Sciences Honors Adviser * Signatures are on file in the Schreyer Honors College. i ABSTRACT This paper examines the merits of intrinsic and extrinsic critical approaches to hip-hop artifacts. To do so, I provide both a neo-Aristotelian and biographical criticism of three songs from ye (2018) by Kanye West. Chapters 1 & 2 consider Roland Barthes’ The Death of the Author and other landmark papers in rhetorical and literary theory to develop an intrinsic and extrinsic approach to criticizing ye (2018), evident in Tables 1 & 2. Chapter 3 provides the biographical antecedents of West’s life prior to the release of ye (2018). Chapters 4, 5, & 6 supply intrinsic (neo-Aristotelian) and extrinsic (biographical) critiques of the selected artifacts. Each of these chapters aims to address the concerns of one of three guiding questions: which critical approaches prove most useful to the hip-hop consumer listening to this song? How can and should the listener construct meaning? Are there any improper ways to critique and interpret this song? Chapter 7 discusses the variance in each mode of critical analysis from Chapters 4, 5, & 6. -

“I Know That We the New Slaves”: an Illusion of Life Analysis of Kanye West’S Yeezus

1 “I KNOW THAT WE THE NEW SLAVES”: AN ILLUSION OF LIFE ANALYSIS OF KANYE WEST’S YEEZUS A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE MASTER OF ARTS BY MARGARET A. PARSON DR. KRISTEN MCCAULIFF - ADVISOR BALL STATE UNIVERSITY MUNCIE, INDIANA MAY 2017 2 ABSTRACT THESIS: “I Know That We the New Slaves”: An Illusion of Life Analysis of Kanye West’s Yeezus. STUDENT: Margaret Parson DEGREE: Master of Arts COLLEGE: College of Communication Information and Media DATE: May 2017 PAGES: 108 This work utilizes an Illusion of Life method, developed by Sellnow and Sellnow (2001) to analyze the 2013 album Yeezus by Kanye West. Through analyzing the lyrics of the album, several major arguments are made. First, Kanye West’s album Yeezus creates a new ethos to describe what it means to be a Black man in the United States. Additionally, West discusses race when looking at Black history as the foundation for this new ethos, through examples such as Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. and Nina Simone’s rhetoric, references to racist cartoons and movies, and discussion of historical events such as apartheid. West also depicts race through lyrics about the imagined Black male experience in terms of education and capitalism. Second, the score of the album is ultimately categorized and charted according to the structures proposed by Sellnow and Sellnow (2001). Ultimately, I argue that Yeezus presents several unique sounds and emotions, as well as perceptions on Black life in America. 3 Table of Contents Chapter One -

Content Experts Reveal for Kids Their Secrets Positive Digital Content for Kids

EDITED BY REMCO PIJPERS & NICOLE VAN Den BOSCH POSITIVE DIGITAL content EXPERTS REVEAL FOR KIDS THEIR SECRETS POSITIVE DIGITAL content FOR KIDS EXP ERTS REVEAL THEIR SECRETS EDITED BY REMCO PIJPERS & NICOLE VAN Den BOSCH POSCON & MIJN KIND ONLIne CHAPTER 3 CHAPTER 5 TABLE OF 56 84 Science & Family Crowdfunding & Coding Het Klokhuis: exploring Science with an App Hello Ruby: Planting the Seed CONTENTS 96 Do-It-Yourself ‘Maker Spaces’ FOREWORD CHAPTER 1 4 26 By neelie Kroes, former Vice-President Testing & Humour of the european commission BB c App: educational and entertaining 40 Laughter & Apps INTRODUCTION 8 Children & Media, Viewpoints from Experts > Sonia Livingstone: Let Kids create and Participate CHAPTER 6 > 98 Patti M. Valkenburg: the teletubbies controversy Co-creating & Characters CHAPTER 4 & the Value of entertainment 5 4 3 2 1 the Playful World of toca Boca 70 Strategy & Innovation the Ravensburger Philosophy: enjoyment, education & togetherness CHAPTER 2 42 Gaming & Education Paxel123: Play & Learn APPENDICES 112 > c hecklist for Positive content for Kids Aged 4-12 > ten Privacy tips for App Developers > About PoSCOn & Mijn Kind online FOREWORD owadays, most of us access online child-abusive material. All of these contribute to content from many different devices, making the Internet a place where children can such as smartphones, tablets and com- have positive experiences. Nputers. Many of us produce online content too. either way, the Internet is a fantastic However, progress in this area is a shared respon- place to learn, play, interact and explore. sibility, and the PoSCOn network – funded by the eU Safer Internet programme – has also been THE My job as european commissioner for the Digi- very active in gathering experts from the public tal Agenda is to ensure that all europeans can and private sector from all over europe in order to benefit from digital technology – including kids, exchange their experiences and devise plans for who are going online at a younger and younger stimulating positive online content for children. -

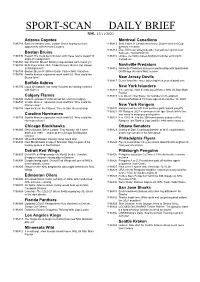

Sport-Scan Daily Brief

SPORT-SCAN DAILY BRIEF NHL 12/11/2020 Arizona Coyotes Montreal Canadiens 1196789 Back for another year, Jordan Gross hoping for more 1196813 Best trades in Canadiens history: Dryden deal set Cup opportunity with Arizona Coyotes dynasty in motion 1196814 Élise Béliveau 'always beside' Canadiens legend Jean Boston Bruins Béliveau, 'not behind him' 1196790 Report: B's could be in division with these teams as part of 1196815 Unique mentality makes Mattias Norlinder enticing to 2020-21 realignment Canadiens 1196791 Doc Emrick: Bruins' Stanley Cup window isn't closed yet 1196792 BHN Puck Links: NHL Trade Rumors, Bruins Get Hosed Nashville Predators In Realignment! 1196816 Nashville Predators announce partnership with sportsbook 1196793 Boston Bruins Hit Billion Dollar Club in NHL Valuation DraftKings ahead of NHL season 1196794 Seattle Kraken eXpansion mock draft 5.0: Who could the Bruins lose? New Jersey Devils 1196817 Devils’ franchise value takes big hit in year of pandemic Buffalo Sabres 1196795 Linus Weissbach 'not really' focused on earning contract New York Islanders with Sabres 1196818 ‘I need help’: How friends saved former NHL All-Star Mark Parrish Calgary Flames 1196819 Life Doesn’t Get Easier for Islanders in Realigned 1196796 Defence prospect Valimaki set for return to Calgary DivisionsPublished 15 hours ago on December 10, 2020 1196797 Seattle Kraken eXpansion mock draft 5.0: Who could the Flames lose? New York Rangers 1196798 How we’d run the Flames: Time to take the neXt step 1196820 Rangers will benefit from perilous path toward playoffs 1196821 NY Rangers 2021 season preview: Igor Shesterkin's time Carolina Hurricanes has come in deep group of goalies 1196799 Seattle Kraken eXpansion mock draft 5.0: Who could the 1196822 It is 2023-24. -

Strategies to Mitigate Negative Social Media Communications in Collegiate Athletics

Walden University ScholarWorks Walden Dissertations and Doctoral Studies Walden Dissertations and Doctoral Studies Collection 2020 Strategies to Mitigate Negative Social Media Communications in Collegiate Athletics Jennifer A. Parks Walden University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.waldenu.edu/dissertations Part of the Communication Commons, and the Sports Management Commons This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Walden Dissertations and Doctoral Studies Collection at ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Walden Dissertations and Doctoral Studies by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Walden University College of Management and Technology This is to certify that the doctoral study by Jennifer A. Parks has been found to be complete and satisfactory in all respects, and that any and all revisions required by the review committee have been made. Review Committee Dr. Deborah Nattress, Committee Chairperson, Doctor of Business Administration Faculty Dr. Jaime Klein, Committee Member, Doctor of Business Administration Faculty Dr. James Savard, University Reviewer, Doctor of Business Administration Faculty Chief Academic Officer and Provost Sue Subocz, Ph.D. Walden University 2020 Abstract Strategies to Mitigate Negative Social Media Communications in Collegiate Athletics by Jennifer A. Parks MBA, Midway University, 2012 BA, University of Kentucky, 1981 Doctoral Study Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of