National Practices Survey Report 2017

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PERSONALITY Personality Not Included

Early Praise for Personality Not Included “Wow. I devoured Personality Not Included, frequently shouting ‘yes!’ as I followed Rohit’s spot-on analysis of a fundamental truth: being faceless doesn’t work anymore. Per- sonality in both people and companies is what customers get passionate about and drives seemingly unlimited success. This is one of those rare books to purchase by the case so you can give copies to employees and investors. But make sure to keep a few for yourself to read and reread so you don’t miss a thing. Bravo!” —David Meerman Scott, bestselling author of The New Rules of Marketing and PR “Personality Not Included breaks down the old barriers between marketing, advertis- ing, and PR and shows people how to nail the single objective of it all: creating pow- erful conversations with your customers and getting them to choose you over the rest.” —Timothy Ferriss, top blogger and #1 New York Times bestselling author of The 4-Hour Workweek “There are two types of small business owners—ones who know they are in the busi- ness of marketing and those who don’t. For either, Personality Not Included is an eye- opening look at what really matters when it comes to delighting your customers. If you want a guide to being more than ordinary, get this book.” —John Jantsch, award-winning blogger and author of Duct Tape Marketing “Just being pretty isn’t enough anymore, today a brand also needs a strong personal- ity to survive. In PNI, Rohit gives you the techniques and tools to help your brand go from wallflower to social butterfly.” —Laura Ries, bestselling author of 22 Immutable Laws of Branding, and cofounder of Ries & Ries “Finally. -

MELT © Heidi Wicks (Thesis)

MELT © Heidi Wicks (Thesis) submitted to the School of Graduate Studies in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts (Creative Writing) Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences Memorial University of Newfoundland May 2019 St. John’s Newfoundland and Labrador MELT A novel by Heidi Wicks 1 Melt shifts between two girls who come of age together during two economically turbulent times - the late ‘90s and present-day - in St. John's, Newfoundland. The women navigate break-ups, tanning beds, spray tans, drifting desires, at least one kid with a raisin up his nose, drunken dancing, infidelity, death, sex in Middle Cove, job loss at the CBC and love loss at the Avalon Mall. Through the pockets of their maddening but beloved city, their friendships and relationships are tested, but their brazen humour and deep- rooted friendship helps them ice-pick through the winter sludge and spring muck and get them through until it’s summer once more. 2 Chapter One “About here?” Cait slices her index finger across the middle of her right thigh, softly. A knife etching a line in butter. “Your father’s not lettin’ you get away with a slit that high.” Tilley Brophy plucks the cigarette from her lips and releases a poof of smoke that curls into the shape of an anchor. She jabs the butt into a heavy crystal ashtray and coughs like her freakin’ lungs are about to vault from her body and splat against her half-brown-carpet, half-brown- wood-panel wall in her house by the Village Mall. -

Comment Submitted by David Crawley Comment View Document

Comment Submitted by David Crawley Comment View document: The notion that my social media identifier should have anything to do with entering the country is a shockingly Nazi like rule. The only thing that this could facilitate anyway is trial by association - something that is known to ensnare innocent people, and not work. What is more this type of thing is repugnant to a free society. The fact that it is optional doesn't help - as we know that this "optional" thing will soon become not-optional. If your intent was to keep it optional - why even bother? Most importantly the rules that we adopt will tend to get adopted by other countries and frankly I don't trust China, India, Turkey or even France all countries that I regularly travel to from the US with this information. We instead should be a beacon for freedom - and we fail in our duty when we try this sort of thing. Asking for social media identifier should not be allowed here or anywhere. Comment Submitted by David Cain Comment View document: I am firmly OPPOSED to the inclusion of a request - even a voluntary one - for social media profiles on the I-94 form. The government should NOT be allowed to dip into users' social media activity, absent probable cause to suspect a crime has been committed. Bad actors are not likely to honor the request. Honest citizens are likely to fill it in out of inertia. This means that the pool of data that is built and retained will serve as a fishing pond for a government looking to control and exploit regular citizens. -

67453 O4 Proposal Opening: May 15, 2015

For public information purposes only; not part of contract. Request for Proposal Number 4958 Z1 Contract Number 67453 O4 Proposal Opening: May 15, 2015 In accordance with Nebraska Revised Statutes §84.712.05(3), the following material(s) has no t been included due to it being marked proprietary. Firespring 1. None In accordan ce with Fed eral U.S. Copyright Law Title 17 U.S.C. Section 101 et seq., Title 1 8 U.S.C. 2319, the following material(s) has not been included due to them being copyrighted. Firespring 1. None May IS, 2015 Dear Selection Committee, Thank you for allowing us to present our capabilities and qualifications for your consideration. It is our privilege to supply you with the enclosed information in response to your request for proposal. We are e)(cited about the opportunity to help your organization increase statewide education on and pubUc awa reness of th e need for organ and tissue donation. Snitily Carr has taken on similar educational and awareness challenges before and has a proven tfack record in helping public health organizations accomplish their campaign goals. We approach these challenges seriously and strategically. To us, it's much more than a campaign-it is a mission. Ultimatel y, it is about people's lives and the well-being of Nebraska families. And to be successful, it requires much more than a client-vendor relat ionship-it requires a strategic partnership. That collaborative approach combined with our e)(perience, resources, and passion for the cause makes us ideally suited to be your communications partner. -

Content Experts Reveal for Kids Their Secrets Positive Digital Content for Kids

EDITED BY REMCO PIJPERS & NICOLE VAN Den BOSCH POSITIVE DIGITAL content EXPERTS REVEAL FOR KIDS THEIR SECRETS POSITIVE DIGITAL content FOR KIDS EXP ERTS REVEAL THEIR SECRETS EDITED BY REMCO PIJPERS & NICOLE VAN Den BOSCH POSCON & MIJN KIND ONLIne CHAPTER 3 CHAPTER 5 TABLE OF 56 84 Science & Family Crowdfunding & Coding Het Klokhuis: exploring Science with an App Hello Ruby: Planting the Seed CONTENTS 96 Do-It-Yourself ‘Maker Spaces’ FOREWORD CHAPTER 1 4 26 By neelie Kroes, former Vice-President Testing & Humour of the european commission BB c App: educational and entertaining 40 Laughter & Apps INTRODUCTION 8 Children & Media, Viewpoints from Experts > Sonia Livingstone: Let Kids create and Participate CHAPTER 6 > 98 Patti M. Valkenburg: the teletubbies controversy Co-creating & Characters CHAPTER 4 & the Value of entertainment 5 4 3 2 1 the Playful World of toca Boca 70 Strategy & Innovation the Ravensburger Philosophy: enjoyment, education & togetherness CHAPTER 2 42 Gaming & Education Paxel123: Play & Learn APPENDICES 112 > c hecklist for Positive content for Kids Aged 4-12 > ten Privacy tips for App Developers > About PoSCOn & Mijn Kind online FOREWORD owadays, most of us access online child-abusive material. All of these contribute to content from many different devices, making the Internet a place where children can such as smartphones, tablets and com- have positive experiences. Nputers. Many of us produce online content too. either way, the Internet is a fantastic However, progress in this area is a shared respon- place to learn, play, interact and explore. sibility, and the PoSCOn network – funded by the eU Safer Internet programme – has also been THE My job as european commissioner for the Digi- very active in gathering experts from the public tal Agenda is to ensure that all europeans can and private sector from all over europe in order to benefit from digital technology – including kids, exchange their experiences and devise plans for who are going online at a younger and younger stimulating positive online content for children. -

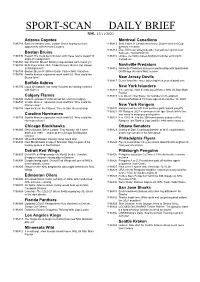

Sport-Scan Daily Brief

SPORT-SCAN DAILY BRIEF NHL 12/11/2020 Arizona Coyotes Montreal Canadiens 1196789 Back for another year, Jordan Gross hoping for more 1196813 Best trades in Canadiens history: Dryden deal set Cup opportunity with Arizona Coyotes dynasty in motion 1196814 Élise Béliveau 'always beside' Canadiens legend Jean Boston Bruins Béliveau, 'not behind him' 1196790 Report: B's could be in division with these teams as part of 1196815 Unique mentality makes Mattias Norlinder enticing to 2020-21 realignment Canadiens 1196791 Doc Emrick: Bruins' Stanley Cup window isn't closed yet 1196792 BHN Puck Links: NHL Trade Rumors, Bruins Get Hosed Nashville Predators In Realignment! 1196816 Nashville Predators announce partnership with sportsbook 1196793 Boston Bruins Hit Billion Dollar Club in NHL Valuation DraftKings ahead of NHL season 1196794 Seattle Kraken eXpansion mock draft 5.0: Who could the Bruins lose? New Jersey Devils 1196817 Devils’ franchise value takes big hit in year of pandemic Buffalo Sabres 1196795 Linus Weissbach 'not really' focused on earning contract New York Islanders with Sabres 1196818 ‘I need help’: How friends saved former NHL All-Star Mark Parrish Calgary Flames 1196819 Life Doesn’t Get Easier for Islanders in Realigned 1196796 Defence prospect Valimaki set for return to Calgary DivisionsPublished 15 hours ago on December 10, 2020 1196797 Seattle Kraken eXpansion mock draft 5.0: Who could the Flames lose? New York Rangers 1196798 How we’d run the Flames: Time to take the neXt step 1196820 Rangers will benefit from perilous path toward playoffs 1196821 NY Rangers 2021 season preview: Igor Shesterkin's time Carolina Hurricanes has come in deep group of goalies 1196799 Seattle Kraken eXpansion mock draft 5.0: Who could the 1196822 It is 2023-24. -

Strategies to Mitigate Negative Social Media Communications in Collegiate Athletics

Walden University ScholarWorks Walden Dissertations and Doctoral Studies Walden Dissertations and Doctoral Studies Collection 2020 Strategies to Mitigate Negative Social Media Communications in Collegiate Athletics Jennifer A. Parks Walden University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.waldenu.edu/dissertations Part of the Communication Commons, and the Sports Management Commons This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Walden Dissertations and Doctoral Studies Collection at ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Walden Dissertations and Doctoral Studies by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Walden University College of Management and Technology This is to certify that the doctoral study by Jennifer A. Parks has been found to be complete and satisfactory in all respects, and that any and all revisions required by the review committee have been made. Review Committee Dr. Deborah Nattress, Committee Chairperson, Doctor of Business Administration Faculty Dr. Jaime Klein, Committee Member, Doctor of Business Administration Faculty Dr. James Savard, University Reviewer, Doctor of Business Administration Faculty Chief Academic Officer and Provost Sue Subocz, Ph.D. Walden University 2020 Abstract Strategies to Mitigate Negative Social Media Communications in Collegiate Athletics by Jennifer A. Parks MBA, Midway University, 2012 BA, University of Kentucky, 1981 Doctoral Study Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of -

Hip Hop As Oral Literature Patrick M

Bates College SCARAB Honors Theses Capstone Projects Spring 5-2016 "That's the Way We Flow": Hip Hop as Oral Literature Patrick M. Smith Bates College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://scarab.bates.edu/honorstheses Recommended Citation Smith, Patrick M., ""That's the Way We Flow": Hip Hop as Oral Literature" (2016). Honors Theses. 177. http://scarab.bates.edu/honorstheses/177 This Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Capstone Projects at SCARAB. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of SCARAB. For more information, please contact [email protected]. “That’s the Way We Flow”: Hip Hop as Oral Literature An Honor Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the Program of African American Studies Bates College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Bachelor of Arts by Patrick Miller Smith Lewiston, Maine 3/28/16 2 Acknowledgments I would like to thank all of my Bates Professors for all of their help during my career at Bates College. Specifically, I would like to thank my thesis advisor, Professor Sue Houchins, for all her hard work, helping me wrestle with this thesis, and for being a source of friendship and guidance since I first met her. Professor Nero, I would also like to send a big thank you to you, you have inspired me countless times and have pushed me since day one. Professors Rubin, Chapman, Jensen, and Carnegie, thank you all very much, each of you helped me on my way to this point and I am very grateful for your guidance. -

Masculinities in Forests; Representations of Diversity

MASCULINITIES IN FORESTS Masculinities in Forests: Representations of Diversity demonstrates the wide variability in ideas about, and practice of, masculinity in different forests, and how these relate to forest management. While forestry is widely considered a masculine domain, a significant portion of the literature on gender and development focuses on the role of women, not men. This book addresses this gap and also highlights how there are significant, demonstrable differences in masculinities from forest to forest. The book develops a simple conceptual framework for considering masculinities, one which both acknowledges the stability or enduring quality of masculinities, but also the significant masculinity-related options available to individual men within any given culture. The author draws on her own life, building on her long-term experience working globally in the conservation and development worlds, also observing masculinities among such professionals. The core of the book examines masculinities, based on long-term ethnographic research in the rural Pacific Northwest of the US; Long Segar, East Kalimantan; and Sitiung, West Sumatra, both in Indonesia. The author concludes by pulling together the various strands of masculine identities and discussing the implications of these various versions of masculinity for forest management. This book will be essential reading for students and scholars of forestry, gender studies and conservation and development, as well as practitioners and NGOs working in these fields. Carol J. Pierce Colfer is a Senior Associate at the Center for International Forestry Research (CIFOR) and Visiting Scholar at Cornell University’s Southeast Asia Program, Ithaca, New York, USA. She is author/editor of numerous books, including co-editor of The Earthscan Reader on Gender and Forests (Routledge, 2017) and Gender and Forests: Climate Change, Tenure, Value Change and Emerging Issues (Routledge, 2016). -

Original.Pdf

ofElon Undergraduate Journal Research in Communications EJ Spring 4 Issue School of Communications Elon University The World of Journals Welcome to the nation’s only journal devoted to undergraduate research in communications. The website of the Council on Undergraduate Research lists about 120 undergraduate research journals nationwide (http://www.cur.org/resources/students/undergraduate_journals/). Some of these focus on a discipline (e.g., Journal of Undergraduate Research in Physics). Others are university-based and multidisci- plinary (e.g., MIT Undergraduate Research Journal). The Elon Journal is the only one with a focus on undergraduate research in journalism, media and communications. The School of Communications at Elon University is the creator and publisher of the online journal. The first issue was published in Spring 2010. The journal is published twice a year, with spring and fall issues, under the editorship of Dr. Byung Lee, associate professor in the School of Communications. The three purposes of the journal are: 1. To publish the best undergraduate research in Elon’s School of Communications each term, 2. To serve as a repository for quality work to benefit future students seeking models for how to do undergraduate research well, and 3. To advance the university’s priority to emphasize undergraduate student research. Articles and other materials in the journal may be freely downloaded, reproduced and redistributed without permission as long as the author and source are properly cited. Student authors retain copyright own- ership of their works. Celebrating Student Research This journal reflects what we enjoy seeing in our students—intellectual maturing. As 18 year olds, some students enter college wanting to earn a degree, but unsure if they want an education. -

The Impact of Social Media on Local Government

THE IMPACT OF SOCIAL MEDIA ON LOCAL GOVERNMENT TRANSPARENCY AND CITIZEN ENGAGEMENT By Lisa Mahajan-Cusack A dissertation submitted to the Graduate School-Newark Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey In partial fulfillment of the requirements For the degree of Doctor of Philosophy School of Public Affairs and Administration Written under the direction of Professor Marc Holzer And approved by ______________________________ ______________________________ ______________________________ ______________________________ Newark, New Jersey May 2016 Copyright © 2016 Lisa Mahajan-Cusack ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION THE IMPACT OF SOCIAL MEDIA ON LOCAL GOVERNMENT TRANSPARENCY AND CITIZEN ENGAGEMENT By LISA MAHAJAN-CUSACK Dissertation Director: Professor Marc Holzer Now that social media has become such a dominant form of communication and interaction among the population in general and in the business world, public sector organizations arguably have an important duty to adopt these tools in order to provide the types of personalized and transparent services expected by citizens and businesses. Governments benefit considerably from the use of these communications and engagement channels, using them to improve the effectiveness of public service delivery (both generally and when faced with emergency situations), to generate information and data, and to build trust-based relationships that help restore confidence in local government. Overall, the use of social media is likely to improve services of local government and contribute to more efficient use of public resources. Adopting and generating value from the use of social media at the local government level requires knowledge and understanding of best practices, as well as the potential pitfalls and challenges. This study is intended to contribute to the knowledge and understanding of social media usage by local governments, based on a diverse sample of local government organizations nationally, which have already established social media practices. -

Shark Makes Perfect Start for E Five Cont

FRIDAY, 11 AUGUST, 2017 Mike Ryan, Edwards=s agent in the U.S., put him in touch with SHARK MAKES PERFECT Eamonn Reilly of BBA Ireland, who initially set out to find Edwards a horse to run at Royal Ascot. While that endeavour START FOR E FIVE didn=t work out, Landshark proved worth the wait after being bought by Reilly for a sale-topping i210,000 at the Goresbridge Breeze-Up Sale in May. Edwards said, AEamonn called me and said, >I have something really special here Bob. It=s not going to be an Ascot horse but he could potentially be a really good horse.=@ Landshark was also a success story for his Goresbridge consignor Egmont Stud, that stud=s principal Mark Flannery having purchased him for just 5,000gns at Tattersalls October Book 2. Edwards has been based at Saratoga for the summer with his 15-horse string, but wasn=t able to make the trip to Ireland for Landshark=s debut, instead traveling with his family to Arizona to move his youngest daughter into college. Cont. p2 IN TDN AMERICA TODAY Landshark was the top-priced lot at Goresbridge | Racing Post photo MCCRAKEN FIRES BULLET FOR TRAVERS ‘TDN Rising Star’ and GI Haskell S. runner-up McCraken by Kelsey Riley (Ghostzapper) breezed a bullet four furlongs in :49.03 (1/31) Bob Edwards=s e Five Racing got off to a fast start in the U.S., over the Oklahoma training track Thursday morning. Click or tap campaigning GI Breeders= Cup Juvenile Fillies Turf winner New here to go straight to TDN America.