Opera by the Book: Defining Music Theater in the Third Reich

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Carl Orffs Hesperische Musik

MATTHIAS JOHANNES PERNERSTORFER / WIEN Carl Orffs hesperische Musik Carl Orffs ‚Antigonae‘ (1940–49) und ‚Oedi pus der Tyrann‘ (1951– 58) nach Sophokles in der Übersetzung von Friedrich Hölderlin sowie der aischyleische ‚Prometheus‘ (1963–67) in der Originalsprache gehören zu den bedeutendsten Beiträgen zur musikalischen Rezeption der Antike im 20. Jahrhundert. Ich folge Stefan Kunze im Gebrauch der Bezeichnung Tragödien-Bearbeitungen für die genannten Bühnenwerke, da „kein musi- kalisches Werk (Vertonung) auf der Grundlage eines Tragödientextes … das Ziel [ist] …, sondern die [interpretative, Anm. d. A.1 ] Darstellung der Tragödie mit musikalischen Mitteln“.2 Es handelt sich um eine Form des Musiktheaters ganz eigener Art – „gleich weit entfernt vom Sprechtheater herkömmlicher Prägung wie von der Oper und von der … Bühnenmusik“.3 Auch wenn der Musikhistoriker Werner Schubert vor einigen Jahren dia- gnostizierte: „Daß es [Orff] … nicht um eine Rekonstruktion antiker Aufführungspraxis ging, muß man heute nicht mehr eigens betonen“,4 so möchte ich anmerken, daß die Tragödien-Bearbeitungen Orffs von vielen Philologen wie Theaterwissenschaftlern, die die musikwissenschaftliche Diskussion nicht mitverfolgen, wohl noch immer – sei es zustimmend oder ablehnend – als Rekonstruktionsversuche rezipiert werden. Der Grund dafür liegt in der zum Teil euphorischen Reaktion von zeitgenössischen Philologen, durch die Orffs Werke den Stellenwert von authentischen Wie- dergaben der altgriechischen Tragödien erreichten. Jahrzehntelang widmete sich Carl Orff den Tragödien-Bearbeitungen, wobei nicht von einem Weg des Komponisten in die Geistes- oder Musik- welt der Antike gesprochen werden kann. DieAntike diente ihm in Form —————————— 1 Zum Interpretationscharakter dieser „Darstellung der Tragödie“ s.u. 2 Kunze 1998, 547. 3 Schubert 1998, 405. 4 Schubert 1998, 403. 122 Matthias Johannes Pernerstorfer ihrer Texte als Medium, das er im Sinne von Höl derlins Antikerezeption mit Blick auf eine abendländische Gegenwart – deshalb ‚hesperisch‘ – gestaltete. -

By H. W. Weigert

. X . By H. W. Weigert V55:190dWOdU H2 028948 AMERICA F AC~S THE WAR A series of Pamphlets by distinguished Americans on problems raised .by the war. 'The following have already appeared. The price of each is 6d. net. r. MR. ·ROOSEVELT SPEAKS-Four Speeches made by PRESIDBMT ROOSEVELT 2. A:-1 AMERICAN LOOKS AT THE BRITISH EMPIRE, by )Aw>S TRUSLOW ADAWS 3· THE FAITH OF AN AMERICAN, by WALTRR MILLIS 4· THE MONROE DOCTRINE TODAY, by GRAYSON KIRK 5· A SUMMONS TO THE FREE, by STEPHEN VINCENT BKNIOI" 6. GER~!AN YOUTH AND THE NAZI DREAM OF VICTORY, by E. Y: HARTSHORN~ . 7· FOOD OR FREEDOM: .THE VITAL BLOCKADE, by WILLIA» AGAR H. GERMANY THEN AND NOW, by ALONZO E: TAYLOR 00 • GERMAN GEOPOLITICS, by H. W. WEIGID<T AMERICA FACES THE WAR. No. 10 --~ -- - GERMAN GEOPOLITICS Bv H. W. WeiQert OXFORD UNIVERSITY PRESS LONDON NEW YORK TORONTO BOMBAY MELBOUR!IIE THis SERIES of Pamphlets, publi~hed under the title 'America Faces the War', originates in the U.S.A. and has mucli the same object as the 'Oxford Pamphlets on World Affairs' so widely read, not only in England, .but all over the world. Just as· Americans have been interested in the English pamphlets, so will the rest of the world wish to see war problems through American eyes.· This material appeared in abridged form in the issue of Harper's Magazine for ·November 1941. Copyright 1941 in United States and Great Britain by Harper lk Brothers. First published ;, England, 1942 First PMb/ished ;, India, July 1942 I PIUNTBD IN INDIA AT THB llADRAS PUBLISHING HOUSE, MADRAS FROM" what source does Hitler draw his inspiration. -

Towner County North Dakota Families <^3

TOWNER COUNTY NORTH DAKOTA FAMILIES <^3 -^V TO! HER COUNTY NORTH DAE OTA FAMILIES ^'WmM••••*•* ••••¥!.» 5917 Myrtle Ave 1958-196 2 Mabel Jacques Hadler Long Beach, 5 v8»iii o vxi i a 1A c V*. fc» TOWNER COXHSfTY, NvD. FAMILIES. VOLUME VI. STIELY, WILLIAM, b 1877; md (2) Oct. 27, 1912, Cando, Rev. Harris; Cora Lagore., b 1876. Lived. Cando Tp. Children: 1. LEON H., Aug. 22, 1900 2. BLANCHE, Dec. 24, 1992 3. HARRY PAUL, 1910-15 STODIG, AXEL, b 1855-95; md Emma ... both foreign birth. Lived Egeland 1915. Ch, 2 of foreign birth: CARL, 1905; EBBA, 1908; NORMA, 1895-1910; WALTER, 1910-15. STOEBEB, FRANK, b Nov, 5., 1891, Streeter, 111.; d June 24, 1954, bur Cando Cath.Cem. fild Sept. 14, 1920, Cando, Fr. Garland; Agnes Stadelberger, b Aug. 17., 1895, Bavaria, Germany. (See Elsperger) She d Feb. 15, 1953, bur Cando Oath.Gem, Farmed, near Cando.; Highway maintenance 1938-53. Vet WWI. Children: 1. Sgt. FRANCIS H., Apr, 2, 1922; lost in bombing mission from New Guinea, Aug., 30., 1944. Bur Jefferson Barracks Nat'l Gem. in group burial Fab. 21, 1950. 2. NANCY M., Feb. 18, 1924| md June 9, 1948, Cando, Fr. Hart; Leo R. Martin, son of J. of Overly. Ch: Martin (1) Meride e Ann, Aug. 195(1), Walla Walla, Wash. (2) Jonathan Ramon, Jan.- 1954, Riveretale, N.D. , STOLER, JOE, born Arcadia, Wiso.; d Feb. 13, 1954, bur Cando } Cath.Cem. Surv by bro & sis: PETS & CHAS. , Wise; Mrs. Mary Bergeson, Eekart, Wise; Mrs. Margaret Elliott, Sask. Can. Preceded by bro 8a sis: NICK, BOB & BILL; Mrs. -

THE WESTERN ALLIES' RECONSTRUCTION of GERMANY THROUGH SPORT, 1944-1952 by Heather L. Dichter a Thesis Subm

SPORTING DEMOCRACY: THE WESTERN ALLIES’ RECONSTRUCTION OF GERMANY THROUGH SPORT, 1944-1952 by Heather L. Dichter A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, Graduate Department of History, University of Toronto © Copyright by Heather L. Dichter, 2008 Library and Archives Bibliothèque et Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de l’édition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A 0N4 Ottawa ON K1A 0N4 Canada Canada Your file Votre référence ISBN: 978-0-494-57981-7 Our file Notre référence ISBN: 978-0-494-57981-7 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non- L’auteur a accordé une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library and permettant à la Bibliothèque et Archives Archives Canada to reproduce, Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve, sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par télécommunication ou par l’Internet, prêter, telecommunication or on the Internet, distribuer et vendre des thèses partout dans le loan, distribute and sell theses monde, à des fins commerciales ou autres, sur worldwide, for commercial or non- support microforme, papier, électronique et/ou commercial purposes, in microform, autres formats. paper, electronic and/or any other formats. The author retains copyright L’auteur conserve la propriété du droit d’auteur ownership and moral rights in this et des droits moraux qui protège cette thèse. Ni thesis. Neither the thesis nor la thèse ni des extraits substantiels de celle-ci substantial extracts from it may be ne doivent être imprimés ou autrement printed or otherwise reproduced reproduits sans son autorisation. -

NARA T733 R10 Guide 97.Pdf

<~ 1985 GUIDES TO GERMAN RECORDS MICROFILMED AT ALEXANDRIA, VA No. 97 Records of the Reich Ministry for the Occupied Eastern Territories (Reichsministerium fiir die besetzten Ostgebiete) and Other Rosenberg Organizations, Part II Microfiche Edition National Archives and Records Administration Washington, DC 1996 TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction ...................................................... i Glossary ......................................................... vi Captured German and Related Records in the National Archives ...................... ix Published Guides to German Records Microfilmed at Alexandria, VA ................. xxiii Suggestions for Citing Microfilm ....................................... xxvii Instructions for Ordering Microfilm ...................................... xxx Appendix A, Documents from the Rosenberg Collection Incorporated Within the National Archives Collection of World War II War Crimes Records, RG 238 ........... xxxi Appendix B, Original Rosenberg Documents Incorporated Within Records of the Office of Strategic Services (OSS), RG 226 .............................. xxxviii Microfiche List .................................................. xxxix INTRODUCTION The Guides to German Records Microfilmed at Alexandria, VA, constitute a series of finding aids to the National Archives and Records Administration (NARA) microfilm publications of seized records of German central, regional, and local government agencies and of military commands and units, as well as of the Nazi Party, its component formations, -

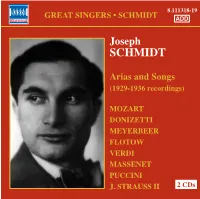

111318-19 Bk Jschmidt EU 10/15/07 2:47 PM Page 8

111318-19 bk JSchmidt EU 10/15/07 2:47 PM Page 8 8.111318-19 CD 1: CD 2: GREAT SINGERS • SCHMIDT Tracks 1, 2, 5 and 9: Tracks 1, 5 and 16: ADD Berlin State Opera Orchestra • Selmar Meyrowitz Orchestra • Felix Günther Tracks 3 and 4: Tracks 2, 6-9, 20-23: Vienna Parlophon Orchestra • Felix Günther Berlin State Opera Orchestra Selmar Meyrowitz Joseph Track 6: Berlin State Opera Orchestra • Clemens Schmalstich Tracks 3, 4, and 13: Berlin State Opera Orchestra SCHMIDT Tracks 7 and 8: Frieder Weissmann Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra • Selmar Meyrowitz Tracks 10-12, 14, 15, 18, and 19: Track 10: Orchestra • Otto Dobrindt With Max Saal, harp Arias and Songs Track 17: Track 11: Orchestra • Clemens Schmalstich Orchestra and Chorus • Clemens Schmalstich (1929-1936 recordings) Tracks 12 and 13: Languages: Berlin Symphony Orchestra • Frieder Weissmann CD 1: MOZART Tracks 14, 15, 17, 18 and 24: Tracks 1, 3-6, 9-13, 16-18, 21-24 sung in German Orchestra of the Staatsoper Berlin Tracks 2, 7, 8, 14, 15, 19, 20 sung in Italian Frieder Weissmann DONIZETTI CD 2: Track 16: Tracks 1-16 sung in German MEYERBEER Orchestra • Leo Blech Track 17 sung in Spanish Tracks 18-23 sung in Italian Tracks 19 and 20: FLOTOW Orchestra • Walter Goehr Tracks 21-23: VERDI Orchestra • Otto Dobrindt MASSENET PUCCINI J. STRAUSS II 2 CDs 8.111318-19 8 111318-19 bk JSchmidt EU 10/15/07 2:47 PM Page 2 Joseph Schmidt (1904-1942) LEHAR: Das Land des Lächelns: MAY: Ein Lied geht um die Welt: 8 Von Apfelblüten eine Kranz (Act I) 3:43 ^ Wenn du jung bist, gehört dir die Welt 3:09 Arias and Songs (1929-1936 recordings) Recorded on 24th October 1929; Recorded in January 1934; Joseph Schmidt’s short-lived career was like that of a 1924 he decided to take the plunge into a secular Mat. -

Madeline Plays Mendelssohn

Madeline Plays Mendelssohn TIMPANOGOS SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA JOHN PEW MUSIC DIRECTOR CELEBRATING Mendelssohn, Violin Concerto 10 YEARS Schubert, Unfinished Symphony February 12 & 13, 2021 7:30 pm Timberline Middle School Concert Program Donna Diana Overture (1894) Emil von Reznicek (1860-1945) Symphony No. 8 “Unfinished” (1822) Franz Schubert (1797-1828) Violin Concerto in E minor, Op. 64 (1845) Felix Mendelssohn (1809-1847) 1. Allegro molto appassionato 2. Andante 3. Allegretto non troppo – Allegro molto vivace Madeline Adkins, violin 1 Violinist Madeline Adkins joined the Utah Symphony as Concertmaster in 2016. Prior to this appointment, she was a member of the Baltimore Symphony Orchestra, performing as Associate Concertmaster for 11 seasons. She was also Concertmaster of the Baltimore Chamber Orchestra from 2008-2016. Adkins performs on the "ex-Chardon" Guadagnini of 1782, graciously loaned by Gabrielle Israelievitch to perpetuate the legacy of her late husband, former Toronto Symphony concertmaster, Jacques Israeliev- itch. She has served as Guest Concertmaster of the Pittsburgh Symphony, the Cincinnati Symphony, the Houston Symphony, the Hong Kong Philharmonic, the Indianapolis Symphony Orchestra, the Grand Teton Music Festival Orchestra, and the Grant Park Symphony Orchestra in Chicago. Adkins has also been a guest artist at numer- ous festivals including the Stellenbosch International Chamber Music Festival in South Africa, the Sarasota Music Festival, Jackson Hole Chamber Music, Music in the Mountains, and the Sewanee Summer Music Festival, as well as a clinician at the National Orchestral Institute, the National Youth Orchestra at Carnegie Hall, and the Haitian Orchestra Institute. In addition, she has served as the Music Director of the NOVA Chamber Music Series in Salt Lake City. -

Curriculum Vitae

Curriculum Vitae Lowell E. Graham 1058 Eagle Ridge El Paso, Texas 79912 Residence Work Home e-mail (915) 581-9741 (915) 747-7825 [email protected] Education Doctor of Musical Arts, Catholic University of America, 1977, Orchestral Conducting Graduate Studies in Music, University of Missouri at Kansas City, summers 1972 and 1973 Master of Arts, University of Northern Colorado, 1971, Clarinet Performance Bachelor of Arts, University of Northern Colorado, 1970, Music Education Military Professional Education Air War College, 1996 Air Command and Staff College, 1983 Squadron Officer School, 1977 Work Experience 2009 to Present Director of Orchestral Activities Music Director, UTEP Symphony Orchestra University of Texas at El Paso El Paso, Texas As the Director or Orchestral Activities I am responsible for the training and development of major orchestral ensembles at the university. I began a tradition of featuring faculty soloists as well as winners of the annual student Concerto Competition, now with an award offered by Olivas Music, providing the orchestra the opportunity to perform significant concerto literature as well as learning the art of accompanying. In 2012, I developed a new chamber orchestra called the “UTEP Virtuosi” focusing on significant string orchestra repertoire. I initiated a concert featuring music in movies and for stage in which that music is presented and integrated via multimedia with lectures and video. It has become the capstone event for the year featuring the artistry of faculty soloists and comments per classical music used in movies and music composed exclusively for that medium. Each year six performances are scheduled. Repertoire for each year covers all eras and styles. -

Sinn Und Geschichte Die Filmische Selbstvergegenwärtigung Der Nationalsozialistischen „Volksgemeinschaft„

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by University of Regensburg Publication Server Sinn und Geschichte Die filmische Selbstvergegenwärtigung der nationalsozialistischen „Volksgemeinschaft„ von Matthias Weiß Regensburger Skripten zur Literaturwissenschaft 1999 Regensburger Skripten zur Literaturwissenschaft Herausgeben von Hans Peter Neureuter µ Redaktion Christine Bühler Band 15 Gedruckt als Manuskript © beim Autor 1999 Diese Arbeit wurde im Sommersemester 1998 von der Philosophischen Fakultät III (Geschichte, Gesellschaft und Geographie) der Universität Regensburg als Magisterarbeit angenommen. Erstgutachter: Prof. Dr. Franz J. Bauer (Neuere und Neueste Geschichte) Zweitgutachter: Prof. Dr. Georg Braungart (Neuere deutsche Literaturwissenschaft) INHALT Einleitung: Der Sinn der Geschichte 5 1. Der Film als ‚sozio-semiotisches‘ System 5 2. Der Film als ‚Aufschreibsystem‘ der modernen Gesellschaft 19 3. Der Mythos des „Dritten Reiches„ 27 A: Der autochthone Sinn der „Volksgemeinschaft„ 38 1. Die Filmgeschichte als Gründungsmythos der „Volksgemeinschaft„ 38 2. „Propaganda„ als Schließung des Sinns 41 a) „Volksaufklärung und Propaganda„ als Ministerium 41 - b) Die Si- cherung der Produktion 45 - c) Die Sicherung von Form und Inhalt 53 - d) Die Präsentation des Sinns 61 3. Die Grenzen des Konsenses 68 B: Aufführungen des autochthonen Sinns 71 1. Das Modell der „Volksgemeinschaft„: Robert Koch. Der Bekämpfer des Todes (1939) 71 a) Intertext: Medizin und Sozialhygiene im „Dritten Reich„ 73 - b) Pro- duktion 77 - c) Text 80 - d) Filmsprache 90 - e) Vergegenwärtigung 92 - f) Exkurs: Zur diachronen Metaphorologie eines Filmbildes 93 - g) Würdigung 97 2. Der Feind der „Volksgemeinschaft„: Jud Süss (1940) 100 a) Intertext: Der Antisemitismus als Staatsdoktrin 102 - b) Produktion 106 - c) Text 114 - d) Filmsprache 127 - e) Vergegenwärtigung 130 - f) Exkurs: Die Inversion der Bilder im NS-Film 135 - g) Würdigung 139 3. -

Brecht's Antigone in Performance

PERFORMANCE PHILOSOPHY RHYTHM AND STRUCTURE: BRECHT’S ANTIGONE IN PERFORMANCE BRUNO C. DUARTE FCSH UNIVERSIDADE NOVA DE LISBOA Brecht’s adaptation of Sophocles’ Antigone in 1948 was openly a political gesture that aspired to the complete rationalization of Greek Tragedy. From the beginning, Brecht made it his task to wrench ancient tragic poetry out of its ‘ideological haze’, and proceeded to dismantle and eliminate what he named the ‘element of fate’, the crucial substance of tragic myth itself. However, his encounter with Hölderlin's unorthodox translation of Antigone, the main source for his appropriation and rewriting of the play, led him to engage in a radical experiment in theatrical practice. From the isolated first performance of Antigone, a model was created—the Antigonemodell —that demanded a direct confrontation with the many obstacles brought about by the foreign structure of Greek tragedy as a whole. In turn, such difficulties brought to light the problem of rhythm in its relation to Brecht’s own ideas of how to perform ancient poetry in a modern setting, as exemplified by the originally alienating figure of the tragic chorus. More importantly, such obstacles put into question his ideas of performance in general, as well as the way they can still resonate in our own understanding of what performance is or might be in a broader sense. 1947–1948: Swabian inflections It is known that upon returning from his American exile, at the end of 1947, Bertolt Brecht began to work on Antigone, the tragic poem by Sophocles. Brecht’s own Antigone premiered in the Swiss city of Chur on February 1948. -

Kodály and Orff: a Comparison of Two Approaches in Early Music Education

ZKÜ Sosyal Bilimler Dergisi, Cilt 8, Sayı 15, 2012 ZKU Journal of Social Sciences, Volume 8, Number 15, 2012 KODÁLY AND ORFF: A COMPARISON OF TWO APPROACHES IN EARLY MUSIC EDUCATION Yrd.Doç.Dr. Dilek GÖKTÜRK CARY Karabük Üniversitesi Safranbolu Fethi Toker Güzel Sanatlar ve Tasarım Fakültesi Müzik Bölümü [email protected] ABSTRACT The Hungarian composer and ethnomusicologist Zoltán Kodály (1882-1967) and the German composer Carl Orff (1895-1982) are considered two of the most influential personalities in the arena of music education during the twentieth-century due to two distinct teaching methods that they developed under their own names. Kodály developed a hand-sign method (movable Do) for children to sing and sight-read while Orff’s goal was to help creativity of children through the use of percussive instruments. Although both composers focused on young children’s musical training the main difference between them is that Kodály focused on vocal/choral training with the use of hand signs while Orff’s main approach was mainly on movement, speech and making music through playing (particularly percussive) instruments. Finally, musical creativity via improvisation is the main goal in the Orff Method; yet, Kodály’s focal point was to dictate written music. Key Words: Zoltán Kodály, Carl Orff, The Kodály Method, The Orff Method. KODÁLY VE ORFF: ERKEN MÜZİK EĞİTİMİNDE KULLANILAN İKİ METODUN BİR KARŞILAŞTIRMASI ÖZET Macar besteci ve etnomüzikolog Zoltán Kodály (1882-1967) ve Alman besteci Carl Orff (1895-1982) geliştirmiş oldukları farklı 2 öğretim metodundan dolayı 20. yüzyılda müzik eğitimi alanında en etkili 2 kişi olarak anılmaktadırlar. Kodály çocukların şarkı söyleyebilmeleri ve deşifre yapabilmeleri için el işaretleri metodu (gezici Do) geliştirmiş, Orff ise vurmalı çalgıların kullanımı ile çocukların yaratıcılıklarını geliştirmeyi hedef edinmiştir. -

The Victor Black Label Discography

The Victor Black Label Discography Victor 25000, 26000, 27000 Series John R. Bolig ISBN 978-1-7351787-3-8 ii The Victor Black Label Discography Victor 25000, 26000, 27000 Series John R. Bolig American Discography Project UC Santa Barbara Library © 2017 John R. Bolig. All rights reserved. ii The Victor Discography Series By John R. Bolig The advent of this online discography is a continuation of record descriptions that were compiled by me and published in book form by Allan Sutton, the publisher and owner of Mainspring Press. When undertaking our work, Allan and I were aware of the work started by Ted Fa- gan and Bill Moran, in which they intended to account for every recording made by the Victor Talking Machine Company. We decided to take on what we believed was a more practical approach, one that best met the needs of record collectors. Simply stat- ed, Fagan and Moran were describing recordings that were not necessarily published; I believed record collectors were interested in records that were actually available. We decided to account for records found in Victor catalogs, ones that were purchased and found in homes after 1901 as 78rpm discs, many of which have become highly sought- after collector’s items. The following Victor discographies by John R. Bolig have been published by Main- spring Press: Caruso Records ‐ A History and Discography GEMS – The Victor Light Opera Company Discography The Victor Black Label Discography – 16000 and 17000 Series The Victor Black Label Discography – 18000 and 19000 Series The Victor Black