The Victor Black Label Discography

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Alshire Records Discography

Alshire Discography by David Edwards, Mike Callahan & Patrice Eyries © 2018 by Mike Callahan Alshire International Records Discography Alshire was located at P.O. Box 7107, Burbank, CA 91505 (Street address: 2818 West Pico Boulevard, Los Angeles, CA 90006). Founded by Al Sherman in 1964, who bought the Somerset catalog from Dick L. Miller. Arlen, Grit and Oscar were subsidiaries. Alshire was a grocery store rack budget label whose main staple was the “101 Strings Orchestra,” which was several different orchestras over the years, more of a franchise than a single organization. Alshire M/S 3000 Series: M/S 3001 –“Oh Yeah!” A Polka Party – Coal Diggers with Happy Tony [1967] Reissue of Somerset SF 30100. Oh Yeah!/Don't Throw Beer Bottles At The Band/Yak To Na Wojence (Fortunes Of War)/Piwo Polka (Beer Polka)/Wanda And Stash/Moja Marish (My Mary)/Zosia (Sophie)/Ragman Polka/From Ungvara/Disc Jocky Polka/Nie Puki Jashiu (Don't Knock Johnny) Alshire M/ST 5000 Series M/ST 5000 - Stephen Foster - 101 Strings [1964] Beautiful Dreamer/Camptown Races/Jeannie With The Light Brown Hair/Oh Susanna/Old Folks At Home/Steamboat 'Round The Bend/My Old Kentucky Home/Ring Ring De Bango/Come, Where My Love Lies Dreaming/Tribute To Foster Medley/Old Black Joe M/ST 5001 - Victor Herbert - 101 Strings [1964] Ah! Sweet Mystery Of Life/Kiss Me Again/March Of The Toys, Toyland/Indian Summer/Gypsy Love Song/Red Mill Overture/Because You're You/Moonbeams/Every Day Is Ladies' Day To Me/In Old New York/Isle Of Our Dreams M/S 5002 - John Philip Sousa, George M. -

Ralph W. Judd Collection on Cross-Dressing in the Performing Arts

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/kt487035r5 No online items Finding Aid to the Ralph W. Judd Collection on Cross-Dressing in the Performing Arts Michael P. Palmer Processing partially funded by generous grants from Jim Deeton and David Hensley. ONE National Gay and Lesbian Archives 909 West Adams Boulevard Los Angeles, California 90007 Phone: (213) 741-0094 Fax: (213) 741-0220 Email: [email protected] URL: http://www.onearchives.org © 2009 ONE National Gay and Lesbian Archives. All rights reserved. Finding Aid to the Ralph W. Judd Coll2007-020 1 Collection on Cross-Dressing in the Performing Arts Finding Aid to the Ralph W. Judd Collection on Cross-Dressing in the Performing Arts Collection number: Coll2007-020 ONE National Gay and Lesbian Archives Los Angeles, California Processed by: Michael P. Palmer, Jim Deeton, and David Hensley Date Completed: September 30, 2009 Encoded by: Michael P. Palmer Processing partially funded by generous grants from Jim Deeton and David Hensley. © 2009 ONE National Gay and Lesbian Archives. All rights reserved. Descriptive Summary Title: Ralph W. Judd collection on Cross-Dressing in the Performing Arts Dates: 1848-circa 2000 Collection number: Coll2007-020 Creator: Judd, Ralph W., 1930-2007 Collection Size: 11 archive cartons + 2 archive half-cartons + 1 records box + 8 oversize boxes + 19 clamshell albums + 14 albums.(20 linear feet). Repository: ONE National Gay and Lesbian Archives. Los Angeles, California 90007 Abstract: Materials collected by Ralph Judd relating to the history of cross-dressing in the performing arts. The collection is focused on popular music and vaudeville from the 1890s through the 1930s, and on film and television: it contains few materials on musical theater, non-musical theater, ballet, opera, or contemporary popular music. -

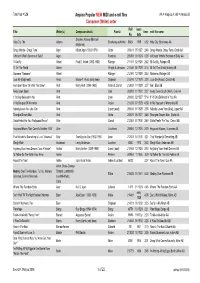

Ampico Popular NEW MIDI and E-Roll Files Composer

Total files = 536 Ampico Popular NEW MIDI and e-roll files AA = Ampico A, AB = Ampico B Composer (Writer) order Roll issue Title Writer(s) Composer details Pianist time midi file name No. date Stephen Adams (Michael Holy City, The Adams Brockway as Kmita 56824 1919 4:52 Holy City, Brockway AA Maybrick) Crazy Words - Crazy Tune Ager Milton Ager (1893-1979) Grofe 208611 05 1927 2:48 Crazy Words, Crazy Tune, Grofe AA I Wonder What's Become of Sally? Ager Fairchild 205191 09 1924 4:28 I Wonder What's Become of Sally AA I'll Get By Ahlert Fred E. Ahlert (1892-1953) Rainger 211171 02 1929 2:42 I'll Get By, Rainger AB I'll Tell The World Ahlert Wright & Johnston 211541 05 1929 3:14 I'll Tell The World (Ahlert) AB Marianne "Marianne" Ahlert Rainger 212191 12 1929 2:44 Marianne, Rainger AB Love Me (Deja) waltz Aivaz Morse-T. Aivaz (only item) Shipman 212241 12 1929 3:20 Love Me (Aivaz), Carroll AB Am I Blue? from "On With The Show" Akst Harry Akst (1894-1963) Arden & Carroll 212031 10 1929 3:37 Am I Blue AB Away Down South Akst Clair 203051 11 1922 2:37 Away Down South (Akst), Clair AA If I'd Only Believed In You Akst Lane 208383 02 1927 5:14 If I'd Only Believed In You AA In My Bouquet Of Memories Akst Arden 210233 07 1928 4:58 In My Bouquet of Memories AB Nobody Loves You Like I Do Akst Lopez (asst) 205531 01 1925 2:38 Nobody Loves You (Akst), Lopez AA Shanghai Dream Man Akst Grofe 208621 05 1927 3:48 Shanghai Dream Man, Grofe AA Gotta Feelin' For You "Hollywood Revue" Alter Carroll 212351 01 1930 2:49 Gotta Feelin' For You, Carroll AB Hugs and -

Brian Casserly, Who Also Goes by the Name "Big B" Plays Trumpet, Trombone and Is Also a Vocalist with the Band

Cornet Chop Suey – Biographies The Cornet Chop Suey Jazz Band has enjoyed a meteoric rise in popularity since its arrival on the jazz scene in 2001. The band's unique front line with Brian Casserly on trumpet, Tom Tucker on cornet, Jerry Epperson on reeds and Brett Stamps on trombone is driven by a powerful rhythm section consisting of Paul Reid on piano, Al Sherman on bass and John Gillick on drums. Best known for a wide variety of styles, Cornet Chop Suey applies its own exciting style to traditional jazz, swing, blues and "big production" numbers. Every performance by Cornet Chop Suey is a high-energy presentation and is always a memorable experience for the audience. Named after a somewhat obscure Louis Armstrong composition, Cornet Chop Suey now has six CD's available. The "St. Louis Armstrong" CD includes many of the tunes performed in the special Louis Armstrong show. The band is in great demand at jazz festivals, jazz cruises, conventions and concerts around the country. Brian Casserly, who also goes by the name "Big B" plays trumpet, trombone and is also a vocalist with the band. A professional musician since the age of 14, Brian has played for many greats in the music business, including Tony Bennett,Tex Beneke, Stan Kenton, Chuck Berry and even Tiny Tim. He has also played the prestigious Monterey Pops Festival for several years. An in-demand session musician, Brian has performed in many commercials, recordings and musicals in the U.S. and Canada and is the past musical director for the S.S. -

JUKEBOX JAZZ by Ian Muldoon* ______

JUKEBOX JAZZ by Ian Muldoon* ____________________________________________________ n 1955 Bill Haley’s Rock Around the Clock was the first rock and roll record to become number one on the hit parade. It had made a stunning introduction in I the opening moments to a film called Blackboard Jungle. But at that time my favourite record was one by Lionel Hampton. I was not alone. Me and my three jazz loving friends couldn’t be bothered spending hard-earned cash on rock and roll records. Our quartet consisted of clarinet, drums, bass and vocal. Robert (nickname Orgy) was learning clarinet; Malcolm (Slim) was going to learn drums (which in due course he did under the guidance of Gordon LeCornu, a percussionist and drummer in the days when Sydney still had a thriving show scene); Dave (Bebop) loved the bass; and I was the vocalist a la Joe (Bebop) Lane. We were four of 120 RAAF apprentices undergoing three years boarding school training at Wagga Wagga RAAF Base from 1955-1957. Of course, we never performed together but we dreamt of doing so and luckily, dreaming was not contrary to RAAF regulations. Wearing an official RAAF beret in the style of Thelonious Monk or Dizzy Gillespie, however, was. Thelonious Monk wearing his beret the way Dave (Bebop) wore his… PHOTO CREDIT WILLIAM P GOTTLIEB _________________________________________________________ *Ian Muldoon has been a jazz enthusiast since, as a child, he heard his aunt play Fats Waller and Duke Ellington on the household piano. At around ten years of age he was given a windup record player and a modest supply of steel needles, on which he played his record collection, consisting of two 78s, one featuring Dizzy Gillespie and the other Fats Waller. -

Louis Armstrong

A+ LOUIS ARMSTRONG 1. Chimes Blues (Joe “King” Oliver) 2:56 King Oliver’s Creole Jazz Band: King Oliver, Louis Armstrong-co; Honore Dutrey-tb; Johnny Dodds-cl; Lil Hardin-p, arr; Arthur “Bud” Scott-bjo; ?Bill Johnson-b; Warren “Baby” Dodds-dr. Richmond, Indiana, April 5, 1923. first issue Gennett 5135/matrix number 11387-A. CD reissue Masters of Jazz MJCD 1. 2. Weather Bird Rag (Louis Armstrong) 2:45 same personnel. Richmond, Indiana, April 6, 1923. Gennett 5132/11388. Masters of Jazz MJCD 1. 3. Everybody Loves My Baby (Spencer Williams-Jack Palmer) 3:03 Fletcher Henderson and his Orchestra: Elmer Chambers, Howard Scott-tp; Louis Armstrong-co, vocal breaks; Charlie Green-tb; Buster Bailey, Don Redman, Coleman Hawkins-reeds; Fletcher Henderson-p; Charlie Dixon- bjo; Ralph Escudero-tu; Kaiser Marshall-dr. New York City, November 22-25, 1924. Domino 3444/5748-1. Masters of Jazz MJCD 21. 4. Big Butter and Egg Man from the West (Armstrong-Venable) 3:01 Louis Armstrong and his Hot Five: Louis Armstrong-co, voc; Edward “Kid” Ory-tb; Johnny Dodds-cl; Lil Hardin Armstrong-p; Johnny St. Cyr-bjo; May Alix-voc. Chicago, November 16, 1926. Okeh 8423/9892-A. Maze 0034. 5. Potato Head Blues (Armstrong) 2:59 Louis Armstrong and his Hot Seven: Louis Armstrong-co; John Thomas-tb; Johnny Dodds-cl; Lil Hardin Armstrong-p; Johnny St. Cyr-bjo; Pete Briggs-tu; Warren “Baby” Dodds-dr. Chicago, May 10, 1927. Okeh 8503/80855-C. Maze 0034. 6. Struttin’ with Some Barbecue (Armstrong) 3:05 Louis Armstrong and his Hot Five. -

Charles Mcpherson Leader Entry by Michael Fitzgerald

Charles McPherson Leader Entry by Michael Fitzgerald Generated on Sun, Oct 02, 2011 Date: November 20, 1964 Location: Van Gelder Studio, Englewood Cliffs, NJ Label: Prestige Charles McPherson (ldr), Charles McPherson (as), Carmell Jones (t), Barry Harris (p), Nelson Boyd (b), Albert 'Tootie' Heath (d) a. a-01 Hot House - 7:43 (Tadd Dameron) Prestige LP 12": PR 7359 — Bebop Revisited! b. a-02 Nostalgia - 5:24 (Theodore 'Fats' Navarro) Prestige LP 12": PR 7359 — Bebop Revisited! c. a-03 Passport [tune Y] - 6:55 (Charlie Parker) Prestige LP 12": PR 7359 — Bebop Revisited! d. b-01 Wail - 6:04 (Bud Powell) Prestige LP 12": PR 7359 — Bebop Revisited! e. b-02 Embraceable You - 7:39 (George Gershwin, Ira Gershwin) Prestige LP 12": PR 7359 — Bebop Revisited! f. b-03 Si Si - 5:50 (Charlie Parker) Prestige LP 12": PR 7359 — Bebop Revisited! g. If I Loved You - 6:17 (Richard Rodgers, Oscar Hammerstein II) All titles on: Original Jazz Classics CD: OJCCD 710-2 — Bebop Revisited! (1992) Carmell Jones (t) on a-d, f-g. Passport listed as "Variations On A Blues By Bird". This is the rarer of the two Parker compositions titled "Passport". Date: August 6, 1965 Location: Van Gelder Studio, Englewood Cliffs, NJ Label: Prestige Charles McPherson (ldr), Charles McPherson (as), Clifford Jordan (ts), Barry Harris (p), George Tucker (b), Alan Dawson (d) a. a-01 Eronel - 7:03 (Thelonious Monk, Sadik Hakim, Sahib Shihab) b. a-02 In A Sentimental Mood - 7:57 (Duke Ellington, Manny Kurtz, Irving Mills) c. a-03 Chasin' The Bird - 7:08 (Charlie Parker) d. -

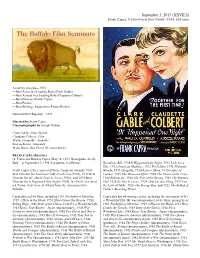

September 3, 2013 (XXVII:2) Frank Capra, IT HAPPENED ONE NIGHT (1934, 105 Min)

September 3, 2013 (XXVII:2) Frank Capra, IT HAPPENED ONE NIGHT (1934, 105 min) Academy Awards—1935: —Best Actor in a Leading Role (Clark Gable) —Best Actress in a Leading Role (Claudette Colbert) —Best Director (Frank Capra) —Best Picture —Best Writing, Adaptation (Robert Riskin) National Film Registry—1993 Directed by Frank Capra Cinematography by Joseph Walker Clark Gable...Peter Warne Claudette Colbert...Ellie Walter Connolly...Andrews Roscoe Karns...Shapeley Ward Bond...Bus Driver #1 (uncredited) FRANK CAPRA (director) (b. Francesco Rosario Capra, May 18, 1897, Bisacquino, Sicily, Italy—d. September 3, 1991, La Quinta, California) Broadway Bill, 1934 It Happened One Night, 1933 Lady for a Day, 1932 American Madness, 1932 Forbidden, 1931 Platinum Frank Capra is the recipient of three Academy Awards: 1939 Blonde, 1931 Dirigible, 1930 Rain or Shine, 1930 Ladies of Best Director for You Can't Take It with You (1938), 1937 Best Leisure, 1929 The Donovan Affair, 1928 The Power of the Press, Director for Mr. Deeds Goes to Town (1936), and 1935 Best 1928 Submarine, 1928 The Way of the Strong, 1928 The Matinee Director for It Happened One Night (1934). In 1982 he received Idol, 1928 So This Is Love?, 1928 That Certain Thing, 1927 For a Lifetime Achievement Award from the American Film the Love of Mike, 1926 The Strong Man, and 1922 The Ballad of Institute. Fisher's Boarding House. Capra directed 54 films, including 1961 Pocketful of Miracles, Capra also has 44 writing credits, including the screenplay of It’s 1959 A Hole in the Head, 1951 Here Comes the Groom, 1950 a Wonderful Life. -

Title Composer Lyricist Arranger Cover Artist Publisher Date Notes Wabash Blues Fred Meinken Dave Ringle Leo Feist Inc

Title Composer Lyricist Arranger Cover artist Publisher Date Notes Wabash Blues Fred Meinken Dave Ringle Leo Feist Inc. 1921 Wabash Cannon Ball Wm Kindt Wm Kindt NPS Calumet Music Co. 1939 High Bass arranged by Bill Burns Wabash Moon Dave Dreyer Dave Dreyer Irving Berlin Inc. 1931 Wagon Wheels Peter DeRose Billy Hill Shapiro, Bernstein & Co. 1934 Wagon Wheels Peter DeRose Billy Hill Geoffrey O'Hara Shapiro, Bernstein & Co., Inc. 1942 Arranged for male voices (T.T.B.B.) Wah-Hoo! Cliff Friend Cliff Friend hbk Crawford Music Corp. 1936 Wait for Me Mary Charlie Tobias Charlie Tobias Harris Remick Music Corp. 1942 Wait Till the Cows Come Home Ivan Caryll Anne Caldwell Chappell & Company Ltd 1917 Wait Till You Get Them Up In The Air, Boys Albert Von Tilzer Lew Brown EEW Broadway Music Corp. 1919 Waitin' for My Dearie Frederick Loewe Alan Jay Lerner Sam Fox Pub. Co. 1947 Waitin' for the Train to Come In Sunny Skylar Sunny Skylar Martin Block Music 1945 Waiting Harold Orlob Harry L. Cort Shapiro, Bernstein & Co. 1918 Waiting at the Church; or, My Wife Won't Let Me Henry E. Pether Fred W. Leigh Starmer Francis, Day & Hunter 1906 Waiting at the End of the Road Irving Berlin Irving Berlin Irving Berlin Inc. 1929 "Waiting for the Robert E. Lee" Lewis F. Muir L. Wolfe Gilbert F.A. Mills 1912 Waiting for the Robert E. Lee Lewis F. Muir L. Wolfe Gilbert Sigmund Spaeth Alfred Music Company 1939 Waiting in the Lobby of Your Heart Hank Thompson Hank Thompson Brenner Music Inc 1952 Wake The Town and Tell The People Jerry Livingston Sammy Gallop Joy Music Inc 1955 Wake Up, America! Jack Glogau George Graff Jr. -

^VOICE to Top ABCD '76 Goal MARCH 26, 1976 VOL

Parishes racing time ^VOICE to top ABCD '76 goal MARCH 26, 1976 VOL. XVIII No. 3 25c As contributions to the continued to arrive at the Arch- half of the families in the Arch- ArchBishop's Charities Drive diocesan Chancery this week, diocese at the time of the Archbishop Coleman F. Carroll meeting on March 10, it is praised the zeal and dedication anticipated that the ABCD of South Florida priests and goal of $2,500,000 will be ex- lauded the generosity of the ceeded. Victim less faithful who have expressed IN VIEW of the sacrificial their concern for the needy spirit of giving already through early donations. exhibited by South Floridians, The drive is continuing Archbishop Carroll said that following the first general there is every indication that report meeting more than one the goal will be met. He week ago when Archbishop reiterated that "this is what Carroll thanked Archdiocesan God intended we should do, priests for their work on the this is our responsibility." drive and noted that many During the weeks since the families had obviously made annual drive — inaugurated 17 sacrifices to increase their years ago by Archbishop pledges of last year. Carroll —began early in IN ADDITION, the Arch- January, thousands of persons bishop cited the "continuing throughout the Archdiocese dedication of men and women have heard first-hand the many in the Archdiocese who have needs of the more than 40 become part of the work of the charitable facilities made Church not only through available by the Church in prayer, sanctification, and South Florida to dependent sacrifice but by personal in- children, youth, drug addicts, volvement in aiding those in unwed mothers, agricultural need." farm workers, the mentally The incomplete total retarded and the aged, through reported at the general meeting donations to the ABCD. -

Newsletter “In the Can.” for a Memorial Tribute to the Late, Great Jazz Writer & Ambassador, Herb Wong

THE GREAT ESCAPE!* j *“Anything that is good jazz is a great escape. When you’re involved in playing or listening to great jazz, no one can get to you.” -Woody Herman Issue No. 31 Presented by: www.dixieswing.com Benny’s Busy Day By Browser Bob Knack Transcriptions are 16 inch discs containing music that was not Benny Goodman must have slept well on the night of available on 78s but sold exclusively to radio stations for air-play. June 6th 1935, because he and his band sure had a busy day! Back then, because of the depression, it is said that He and his Rhythm Makers Orchestra went into the studio and in transcriptions actually outsold 78 RPM records. During the one sitting recorded 50 tracks (one a medley of two) for the RCA 1970’s, there was a “direct-to-disc” recording craze where bands transcription service. recorded a “live” session directly to a master disc with no editing The backstory: Benny in 1934 had organized a big band or mixing. Bands such as Harry James, Les Brown, Buddy Rich, for Billy Rose’s Music Hall in New York City. It was run as a and Benny Goodman participated in the production of these supper club with vaudeville acts opening and the Goodman band audiophile LP’s. Fact is Benny’s 1935 transcriptions were the playing for dancing later. A fortuitous aspect of the engagement same as direct-to-disc, and all 50 sides were done with one take! was that a radio broadcast was arranged for the performances So on June 6, Goodman, happy to have the work, went and Benny got some welcome exposure. -

FOREST LAWN MEMORIAL PARK Hollywood Hills Orry George Kelly December 31, 1897 - February 27, 1964 Forest Lawn Memorial Park Hollywood Hills

Welcome to FOREST LAWN MEMORIAL PARK Hollywood Hills Orry George Kelly December 31, 1897 - February 27, 1964 Forest Lawn Memorial Park Hollywood Hills Order of Service Waltzing Matilda Played by the Forest Lawn Organist – Anthony Zediker Eulogy to be read by Jack. L. Warner Pall Bearers, To be Announced. Photo by Tony Duran Orry George Kelly December 31, 1897 - February 27, 1964 Forest Lawn Memorial Park Hollywood Hills Photo by Tony Duran Orry George Kelly December 31, 1897 - February 27, 1964 Forest Lawn Memorial Park Hollywood Hills Orry-Kelly Filmography 1963 Irma la Douce 1942 Always in My Heart (gowns) 1936 Isle of Fury (gowns) 1963 In the Cool of the Day 1942 Kings Row (gowns) 1936 Cain and Mabel (gowns) 1962 Gypsy (costumes designed by) 1942 Wild Bill Hickok Rides (gowns) 1936 Give Me Your Heart (gowns) 1962 The Chapman Report 1942 The Man Who Came to Dinner (gowns) 1936 Stage Struck (gowns) 1962 Five Finger Exercise 1941 The Maltese Falcon (gowns) 1936 China Clipper (gowns) (gowns: Miss Russell) 1941 The Little Foxes (costumes) 1936 Jailbreak (gowns) 1962 Sweet Bird of Youth (costumes by) 1941 The Bride Came C.O.D. (gowns) 1936 Satan Met a Lady (gowns) 1961 A Majority of One 1941 Throwing a Party (Short) 1936 Public Enemy’s Wife (gowns) 1959 Some Like It Hot 1941 Million Dollar Baby (gowns) 1936 The White Angel (gowns) 1958 Auntie Mame (costumes designed by) 1941 Affectionately Yours (gowns) 1936 Murder by an Aristocrat (gowns) 1958 Too Much, Too Soon (as Orry Kelly) 1941 The Great Lie (gowns) 1936 Hearts Divided (gowns)