Text Preview

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Distal Radius System 2.5

PRODUCT INFORMATION Distal Radius System 2.5 APTUS® Wrist 2 | Distal Radius System 2.5 Contents 3 A New Generation of Radius Plates 4 One System for Primary and Secondary Reconstruction 6 ADAPTIVE II Distal Radius Plates 8 FPL Plates 10 Hook Plates 11 Lunate Facet Plates 12 Rim Plates 13 Fracture Plates 14 Correction Plates 15 Volar Frame Plates 16 Extra-Articular Plates 17 Small Fragment Plates 18 Dorsal Frame Plates 19 XL Plates 20 Distal Ulna Plates 21 Fracture Treatment Concept 22 Technology, Biomechanics, Screw Features 24 Precisely Guided Screw Placement 25 Instrument for Reconstruction of the Volar Tilt 26 Storage 27 Overview Screw Trajectories 29 Ordering Information 47 Bibliography For further information regarding the APTUS product line visit: www.medartis.com Medartis, APTUS, MODUS, TriLock, HexaDrive and SpeedTip are registered trademarks of Medartis AG / Medartis Holding AG, 4057 Basel, Switzerland www.medartis.com Distal Radius System 2.5 | 3 A New Generation of Radius Plates Why is a new generation of radius plates needed? Distal radius fractures are the most common fractures of the stable plate systems have enabled open reduction and inter- upper extremities. The knowledge of these fractures has grown nal fixation to become an established treatment method for enormously over the last years. Treatment concepts have like- intra- and extra-articular distal radius fractures. These sys- wise been refined. It is now generally accepted that the best tems have enabled even severe extension fractures with dor- possible anatomical reconstruction of the radiocarpal joint sal defect zones to be precisely repositioned and treated with (RCJ) and distal radioulnar joint (DRUJ) to produce a func- osteosynthesis via volar access without the need for additional tional outcome is a requirement. -

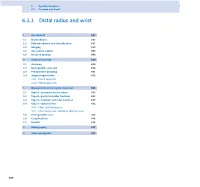

6.3.3 Distal Radius and Wrist

6 Specific fractures 6.3 Forearm and hand 6.3.3 Distal radius and wrist 1 Assessment 657 1.1 Biomechanics 657 1.2 Pathomechanics and classification 657 1.3 Imaging 658 1.4 Associated lesions 659 1.5 Decision making 659 2 Surgical anatomy 660 2.1 Anatomy 660 2.2 Radiographic anatomy 660 2.3 Preoperative planning 661 2.4 Surgical approaches 662 2.4.1 Dorsal approach 2.4.2 Palmar approach 3 Management and surgical treatment 665 3.1 Type A—extraarticular fractures 665 3.2 Type B—partial articular fractures 667 3.3 Type C—complete articular fractures 668 3.4 Ulnar column lesions 672 3.4.1 Ulnar styloid fractures 3.4.2 Ulnar head, neck, and distal shaft fractures 3.5 Postoperative care 674 3.6 Complications 676 3.7 Results 676 4 Bibliography 677 5 Acknowledgment 677 656 PFxM2_Section_6_I.indb 656 9/19/11 2:45:49 PM Authors Daniel A Rikli, Doug A Campbell 6.3.3 Distal radius and wrist of this stable pivot. The TFCC allows independent flexion/ 1 Assessment extension, radial/ulnar deviation, and pronation/supination of the wrist. It therefore plays a crucial role in the stability of 1.1 Biomechanics the carpus and forearm. Significant forces are transmitted across the ulnar column, especially while making a tight fist. The three-column concept (Fig 6.3.3-1) [1] is a helpful bio- mechanical model for understanding the pathomechanics of 1.2 Pathomechanics and classification wrist fractures. The radial column includes the radial styloid and scaphoid fossa, the intermediate column consists of the Virtually all types of distal radial fractures, with the exception lunate fossa and sigmoid notch (distal radioulnar joint, DRUJ), of dorsal rim avulsion fractures, can be produced by hyper- and the ulnar column comprises the distal ulna (DRUJ) with extension forces [2]. -

Superficial (And Intermediate) Cervical Plexus Block

Superficial (and Intermediate) Cervical Plexus Block Indications: -Tympanomastoid surgery. When combined with the auricular branch of the vagus (‘nerve of arnold’) by infiltrating subcutaneously into the medial side of the tragus), obviates the need for opiates. -Pinnaplasty or Otoplasty -Lymph node excision (within the anterior and posterior triangles of the neck) -Clavicular surgery or fractures (may require intermediate cervical plexus block and its combination with interscalene block, see below) -Central Venous Catheters: Renal replacement therapy central venous catheters, tunnelled central venous catheters and portacaths inserted into the subclavian or jugular veins (may require combination with ‘Pecs 1’ block for component of pain below the clavicle) -Tracheostomy (see below discussion on safety profile of performing bilateral blocks and risks of respiratory distress due to phrenic nerve or recurrent largyngeal nerve block) -More commonly in adults: thyroid (again, bilateral) and carotid surgery Contraindications: -local sepsis or rash Anatomy: The cervical plexus arises from C1-C4 mixed spinal nerves (fig. 1): Somatic sensory branches: -arise from C2-C4 as the mixed spinal nerves leave the sulcus between the anterior and posterior tubercles of the transverse process (note C7 does not have an anterior tubercle or bifid spinous process): -pass between longus capitis and middle scalene perforating the prevertebral fascia. Note at C4 level the anterior scalene has largely disappeared having taken the bulk of its vertebral bony origin lower down. The bulkiest of the scalene muscles is the middle scalene and remains in view at this level: -then pass behind the internal jugular vein out into the potential space between the investing layer of deep fascia ensheathing the sternocleidomastoid, and the prevertebral layer of deep fascia covering levator scapulae (fig. -

33. Spinal Nerves. Cervical Plexus

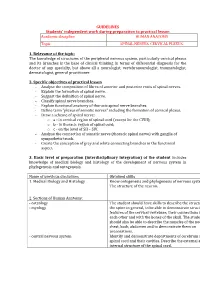

GUIDELINES Students’ independent work during preparation to practical lesson Academic discipline HUMAN ANATOMY Topic SPINAL NERVES. CERVICAL PLEXUS. 1. Relevance of the topic: The knowledge of structures of the peripheral nervous system, particularly cervical plexus and its branches is the base of clinical thinking in terms of differential diagnosis for the doctor of any specialty, but above all a neurologist, vertebroneurologist, traumatologist, dermatologist, general practitioner. 2. Specific objectives of practical lesson - Analyse the composition of fibres of anterior and posterior roots of spinal nerves. - Explain the formation of spinal nerve. - Suggest the definition of spinal nerve. - Classify spinal nerve branches. - Explain functional anatomy of thoracic spinal nerve branches. - Define term "plexus of somatic nerves" including the formation of cervical plexus. - Draw a scheme of spinal nerve: o а - in cervical region of spinal cord (except for the CVIII); o b - in thoracic region of spinal cord; o c - on the level of SII – SIV. - Analyse the connection of somatic nerve (thoracic spinal nerve) with ganglia of sympathetic trunk. - Create the conception of grey and white connecting branches in the functional aspect. 3. Basic level of preparation (interdisciplinary integration) of the student includes knowledge of medical biology and histology of the development of nervous system in phylogenesis and ontogenesis. Name of previous disciplines Obtained skills 1. Medical Biology and Histology Know ontogenesis and phylogenesis of nervous system. The structure of the neuron. 2. Sections of Human Anatomy: - osteology The student should have skills to describe the structure of - myology the spine in general, to be able to demonstrate structural features of the cervical vertebrae, their connections with each other and with the bones of the skull. -

Sustentaculum Lunatum: Appreciation of the Palmar Lunate Facet in Management of Complex Intra-Articular Fractures of the Distal Radius

A Review Paper Sustentaculum Lunatum: Appreciation of the Palmar Lunate Facet in Management of Complex Intra-Articular Fractures of the Distal Radius Ebrahim Paryavi, MD, MPH, Matthew W. Christian, MD, W. Andrew Eglseder, MD, and Raymond A. Pensy, MD key role in restoring the anatomy of the palmar distal radial Abstract metaphysis during internal fixation. This fragment in com- Fracture of the distal radius is the most common wrist minuted fractures was first ascribed special importance by injury. Treatment of complex intra-articular fractures of Melone5 in his description of common fracture patterns. In the distal radius requires an accurate diagnosis of the the present article, we describe the anatomical characteristics fracture pattern and a thoughtful approach to fixation. of the sustentaculum lunatum and the clinical relevance of We propose a new term, sustentaculum lunatum, for this fragment to management of fractures of the distal radius. the palmar lunate facet. The sustentaculum lunatum deserves specific attention because of its importance Classification in load transmission across the radiocarpal joint. It is A variety of classification systems have been proposed to char- acterize and guide treatment of fractures of the distal radius. also key to restoring the anatomy of the palmarAJO distal The earliest descriptions of fracture patterns were presented by radial metaphysis during internal fixation. We provide Castaing6 and Frykman7 in the 1960s. The Frykman classifica- a review of the structure and function of the susten- tion historically has been popular but is limited in accuracy in taculum lunatum and describe fixation techniques. This its characterization of fragments and their displacement and is article is intended to promote awareness of this frag- limited in its ability to guide treatment. -

Shoulder Anatomy & Clinical Exam

MSK Ultrasound - Spine - Incheon Terminal Orthopedic Private Clinic Yong-Hyun, Yoon C,T-spine Basic Advanced • Medial branch block • C-spine transforaminal block • Facet joint block • Thoracic paravertebral block • C-spine intra-discal injection • Superficial cervical plexus block • Vagus nerve block • Greater occipital nerve block(GON) • Third occipital nerve block(TON) • Hydrodissection • Brachial plexus(1st rib level) • Suboccipital nerve • Stellate ganglion block(SGB) • C1, C2 nerve root, C2 nerve • Brachial plexus block(interscalene) • Recurrent laryngeal nerve • Serratus anterior plane • Cervical nerve root Cervical facet joint Anatomy Diagnosis Cervical facet joint injection C-arm Ultrasound Cervical medial branch Anatomy Nerve innervation • Medial branch • Same level facet joint • Inferior level facet joint • Facet joint • Dual nerve innervation Cervical medial branch C-arm Ultrasound Cervical nerve root Anatomy Diagnosis • Motor • Sensory • Dermatome, myotome, fasciatome Cervical nerve root block C-arm Ultrasound Stallete ganglion block Anatomy Injection Vagus nerve Anatomy Injection L,S-spine Basic Advanced • Medial branch block • Lumbar sympathetic block • Facet joint block • Lumbar plexus block • Superior, inferior hypogastric nerve block • Caudal block • Transverse abdominal plane(TAP) block • Sacral plexus block • Epidural block • Hydrodissection • Interlaminal • Pudendal nerve • Transforaminal injection • Genitofemoral nerve • Superior, inferior cluneal nerve • Rectus abdominal sheath • Erector spinae plane Lumbar facet -

The Peripheral Nervous System

The Peripheral Nervous System Dr. Ali Ebneshahidi Peripheral Nervous System (PNS) – Consists of 12 pairs of cranial nerves and 31 pairs of spinal nerves. – Serves as a critical link between the body and the central nervous system. – peripheral nerves contain an outermost layer of fibrous connective tissue called epineurium which surrounds a thinner layer of fibrous connective tissue called perineurium (surrounds the bundles of nerve or fascicles). Individual nerve fibers within the nerve are surrounded by loose connective tissue called endoneurium. Cranial Nerves Cranial nerves are direct extensions of the brain. Only Nerve I (olfactory) originates from the cerebrum, the remaining 11 pairs originate from the brain stem. Nerve I (Olfactory)- for the sense of smell (sensory). Nerve II (Optic)- for the sense of vision (sensory). Nerve III (Oculomotor)- for controlling muscles and accessory structures of the eyes ( primarily motor). Nerve IV (Trochlear)- for controlling muscles of the eyes (primarily motor). Nerve V (Trigeminal)- for controlling muscles of the eyes, upper and lower jaws and tear glands (mixed). Nerve VI (Abducens)- for controlling muscles that move the eye (primarily motor). Nerve VII (Facial) – for the sense of taste and controlling facial muscles, tear glands and salivary glands (mixed). Nerve VIII (Vestibulocochlear)- for the senses of hearing and equilibrium (sensory). Nerve IX (Glossopharyngeal)- for controlling muscles in the pharynx and to control salivary glands (mixed). Nerve X (Vagus)- for controlling muscles used in speech, swallowing, and the digestive tract, and controls cardiac and smooth muscles (mixed). Nerve XI (Accessory)- for controlling muscles of soft palate, pharynx and larynx (primarily motor). Nerve XII (Hypoglossal) for controlling muscles that move the tongue ( primarily motor). -

Palmar Plating of Distal Radius Fractures – Pearls and Pitfalls

Palmar Plating of Distal Radius Fractures – Pearls and Pitfalls Michael S. Bednar, M.D. Chief, Hand Surgery Professor, Dept. of Ortho Surgery & Rehab Loyola University – Chicago Disclosure n Consultant – Biomet/Zimmer Evolution in Treatment of Distal Radius Fractures 1 External Fixation and Percutaneous Pinning External Fixation and Percutaneous Pinning External Fixation 2 Percutaneous Pinning Percutaneous Pinning Old ORIF concept: n Dorsally displaced = Dorsal plate n Palmarly displaced = Palmar plate 3 Goals of Treatment n ORIF n Indications n Displaced palmar intra and extra- articular fractures ORIF n Palmar Barton and Smith Fractures n ORIF is accepted form of treatment n Palmar plate is well tolerated n Exposure radial to FCR has low morbidity 4 Cohort Studies Volar Fixed Angle n Orbay, J. L., Fernandez, D.L. (2002). 31 partients n Kamano, M., Y. Honda, et al. (2002). 33 patients Follows the contour of the subchondral bone Pegs and screw locked into plate support articular surface when placed directed under the subchondral bone. 5 Distally angled pegs neutralize dorsal forces Joint Reaction Force §.Volar buttress neutralizes volar forces Volar locking plating indications • Dorsal or palmar angulation • Intra-articular fractures • Comminuted fractures • Osteopenia Volar locking plating indications • Dorsal or palmar angulation • Intra-articular fractures • Comminuted fractures • Osteopenia 6 3 Months Post OP Wrist Fractures = ORIF 7 ORIF 8 No metal over radial styloid, causes tendon ruputure Complications – Wrong Fracture Type n -

Locking Versus Nonlocking Palmar Plate Fixation of Distal Radius Fractures

n Feature Article SPOTLIGHT ON upper extremity Locking Versus Nonlocking Palmar Plate Fixation of Distal Radius Fractures MICHAEL OSTI, MD; CHRISTOPH MITTLER, MD; RICHARD ZINNECKER, MD; CHRISTOPH WESTREICHER, MD; CLEMENS ALLHOFF, MD; KARL PETER BENEDETTO, MD abstract Full article available online at Healio.com/Orthopedics. Search: 20121023-18 This study compared functional and radiological outcomes after treatment of extension- type distal radius fractures with conventional titanium nonlocking T-plates or titanium 1.5-mm locking plates. A total of 60 patients were included and followed for 4 to 7 years after receiving nonlocking T-plates (group A; n530) or locking plates (group B; n530) with and without dorsal bone grafting. Bone grafting was significantly more of- ten performed in the nonlocking group to increase dorsal fracture fixation and stability (P,.003). Pre- and postoperative and follow-up values for palmar tilt, radial inclination, radial shortening, and ulnar variance were recorded. Age, sex, and fracture type were similarly distributed between the 2 groups. Postoperative and follow-up evaluation re- vealed equal allocation of intra-articular step formation and osteoarthritic changes to both groups. The overall complication rate was 25%. Compared with the nonlocking system, patients undergoing locking plate fixation presented with statistically signifi- cantly better values for postoperative palmar tilt (5.53° vs 8.15°; P,.02) and radial incli- nation (22.13° vs 25.03°; P,.02). However, forearm pronation was significantly better in group A (P,.005). At follow-up, radial inclination tended to approach a statistically significant difference in favor of group B. All clinical assessment, including Mayo wrist score, Disabilities of the Arm, Shoulder, and Hand score, Green and O’Brien score, Gartland and Werley score, visual analog scale score, and grip strength, yielded no statistically significant difference between the 2 groups. -

Palmar and Dorsal Fixed-Angle Plates in AO C-Type

Jakubietz et al. Journal of Orthopaedic Surgery and Research 2012, 7:8 http://www.josr-online.com/content/7/1/8 RESEARCH ARTICLE Open Access Palmar and dorsal fixed-angle plates in AO C-type fractures of the distal radius: is there an advantage of palmar plates in the long term? Michael G Jakubietz1*, Joerg G Gruenert2 and Rafael G Jakubietz1 Abstract Background: Current surgical approaches to the distal radius include dorsal and palmar plate fixation. While palmar plates have gained widespread popularity, few reports have provided data on long term clinical outcomes in comparison. This paper reports the result of a randomised clinical study comparing dorsal Pi plates and palmar, angle-stable plates for treatment of comminuted, intraarticular fractures of the distal radius over the course of twelve months. Methods: 42 patients with unilateral, intraarticular fractures of the distal radius were included and randomised to 2 groups, 22 were treated with a palmar plate, 20 received a dorsal Pi-plate. Results were evaluated after 6 weeks, 3, 6 and 12 months postoperatively focussing on functional recovery as well as radiological results. Results: The palmar plate group demonstrated significantly better results regarding range of motion and grip strength over the course of 12 months. While a comparable increase in function was observed in both groups, the better results from the early postoperative period in the palmar plate group prevailed over the whole course. Radiological results showed a significantly increased palmar tilt and carpal sag in dorsal plates, with other radiological parameters being comparable. Pain levels were decreased in dorsal plates after hardware removal and failed to show significant differences after 12 months. -

Reconstruction of Complex Defects of the Extracranial Facial Nerve: Technique of “The Trifurcation Approach”

European Archives of Oto-Rhino-Laryngology (2019) 276:1793–1798 https://doi.org/10.1007/s00405-019-05418-4 HEAD AND NECK Reconstruction of complex defects of the extracranial facial nerve: technique of “the trifurcation approach” Dirk Beutner1 · Maria Grosheva2 Received: 28 January 2019 / Accepted: 31 March 2019 / Published online: 4 April 2019 © Springer-Verlag GmbH Germany, part of Springer Nature 2019 Abstract Purpose Reconstruction of complex defects of facial nerve (FN) after extensive cancer surgery requires individualized solutions. We describe the trifurcation technique as a modifcation of the combined approach on example of two patients with locally advanced parotid cancer. Methods Due to perineural invasion, extensive resection of the FN from the mastoid segment to the peripheral branches was required. For reanimation of the upper face, a complex cervical plexus graft was sutured end-to-end to the mastoid segment of the FN trunk. The branches of the graft enabled reanimation of three peripheral temporal and zygomatic branches. The mandibular branch was sutured end-to-side to the hypoglossal nerve (hypoglossal–facial nerve transfer, HFNT). Addition- ally, the buccal branch was independently reanimated with ansa cervicalis. Results Facial reanimation was successful in both patients. Good resting tone and voluntary movement were achieved with a mild degree of synkinesis after 13 months. Patient 1 showed the Sunnybrook (SB) composite score 69 [76 (voluntary move- ment score) − 0 (resting symmetry score) − 7 (synkinesis score)]. In patient 2, the SB composite score was 76 (80 − 0 − 4, respectively). Conclusions In this trifurcation approach, cervical cutaneous plexus provides a long complex nerve graft, which allows bridging the gap between proximal FN stump and several peripheral branches without great expenditure. -

TMPR™ Total Metacarpophalangeal Replacement Operative Technique

TMPR™ Total Metacarpophalangeal Replacement Operative Technique Balanced Natural Movement Contents Section 1 | Introduction 3 Section 2 | Operative technique 4 Contents Section 3 | Inventory 12 Section 4 | Sizing chart 13 Manufactured by MatOrtho Limited 13 Mole Business Park | Randalls Road | Leatherhead | Surrey | KT22 7BA | United Kingdom T: +44 (0)1372 224200 | [email protected] For more information visit: www.MatOrtho.com © MatOrtho Limited 2016. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording or any information storage and retrieval system. 2 | TMPR™ Total Metacarpophalangeal Replacement | Operative Technique Section 1 | TMPR™ implant design features Construction is of standard joint replacement materials i.e. cobalt chrome and ultrahigh molecular weight polyethylene. The metacarpal bearing is a section of a sphere narrowed from side to side, with an offset centre of rotation which provides a cam action to tighten the collateral ligaments during flexion. The dorsal surface has a groove for the location of the extensor tendon. Flanges cover the front and back of the Introduction metacarpal neck which is otherwise cut square. The phalangeal surface is a disc with a shallow concave surface congruent with the metacarpal head. Both implant stems extend to the mid shaft to spread the fixation stresses. The thin metacarpal stem slides in a separate polyethylene plug. The metacarpal plug has thin flexible fins in the shape of truncated triangles conforming to the endosteal surface. The phalangeal stem bears similar fins in the shape of rounded rectangles conforming to the proximal phalanx canal.