Mapping Sensory Nerve Communications Between Peripheral Nerve Territories

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Clinical Presentations of Lumbar Disc Degeneration and Lumbosacral Nerve Lesions

Hindawi International Journal of Rheumatology Volume 2020, Article ID 2919625, 13 pages https://doi.org/10.1155/2020/2919625 Review Article Clinical Presentations of Lumbar Disc Degeneration and Lumbosacral Nerve Lesions Worku Abie Liyew Biomedical Science Department, School of Medicine, Debre Markos University, Debre Markos, Ethiopia Correspondence should be addressed to Worku Abie Liyew; [email protected] Received 25 April 2020; Revised 26 June 2020; Accepted 13 July 2020; Published 29 August 2020 Academic Editor: Bruce M. Rothschild Copyright © 2020 Worku Abie Liyew. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. Lumbar disc degeneration is defined as the wear and tear of lumbar intervertebral disc, and it is mainly occurring at L3-L4 and L4-S1 vertebrae. Lumbar disc degeneration may lead to disc bulging, osteophytes, loss of disc space, and compression and irritation of the adjacent nerve root. Clinical presentations associated with lumbar disc degeneration and lumbosacral nerve lesion are discogenic pain, radical pain, muscular weakness, and cutaneous. Discogenic pain is usually felt in the lumbar region, or sometimes, it may feel in the buttocks, down to the upper thighs, and it is typically presented with sudden forced flexion and/or rotational moment. Radical pain, muscular weakness, and sensory defects associated with lumbosacral nerve lesions are distributed on -

Superficial (And Intermediate) Cervical Plexus Block

Superficial (and Intermediate) Cervical Plexus Block Indications: -Tympanomastoid surgery. When combined with the auricular branch of the vagus (‘nerve of arnold’) by infiltrating subcutaneously into the medial side of the tragus), obviates the need for opiates. -Pinnaplasty or Otoplasty -Lymph node excision (within the anterior and posterior triangles of the neck) -Clavicular surgery or fractures (may require intermediate cervical plexus block and its combination with interscalene block, see below) -Central Venous Catheters: Renal replacement therapy central venous catheters, tunnelled central venous catheters and portacaths inserted into the subclavian or jugular veins (may require combination with ‘Pecs 1’ block for component of pain below the clavicle) -Tracheostomy (see below discussion on safety profile of performing bilateral blocks and risks of respiratory distress due to phrenic nerve or recurrent largyngeal nerve block) -More commonly in adults: thyroid (again, bilateral) and carotid surgery Contraindications: -local sepsis or rash Anatomy: The cervical plexus arises from C1-C4 mixed spinal nerves (fig. 1): Somatic sensory branches: -arise from C2-C4 as the mixed spinal nerves leave the sulcus between the anterior and posterior tubercles of the transverse process (note C7 does not have an anterior tubercle or bifid spinous process): -pass between longus capitis and middle scalene perforating the prevertebral fascia. Note at C4 level the anterior scalene has largely disappeared having taken the bulk of its vertebral bony origin lower down. The bulkiest of the scalene muscles is the middle scalene and remains in view at this level: -then pass behind the internal jugular vein out into the potential space between the investing layer of deep fascia ensheathing the sternocleidomastoid, and the prevertebral layer of deep fascia covering levator scapulae (fig. -

33. Spinal Nerves. Cervical Plexus

GUIDELINES Students’ independent work during preparation to practical lesson Academic discipline HUMAN ANATOMY Topic SPINAL NERVES. CERVICAL PLEXUS. 1. Relevance of the topic: The knowledge of structures of the peripheral nervous system, particularly cervical plexus and its branches is the base of clinical thinking in terms of differential diagnosis for the doctor of any specialty, but above all a neurologist, vertebroneurologist, traumatologist, dermatologist, general practitioner. 2. Specific objectives of practical lesson - Analyse the composition of fibres of anterior and posterior roots of spinal nerves. - Explain the formation of spinal nerve. - Suggest the definition of spinal nerve. - Classify spinal nerve branches. - Explain functional anatomy of thoracic spinal nerve branches. - Define term "plexus of somatic nerves" including the formation of cervical plexus. - Draw a scheme of spinal nerve: o а - in cervical region of spinal cord (except for the CVIII); o b - in thoracic region of spinal cord; o c - on the level of SII – SIV. - Analyse the connection of somatic nerve (thoracic spinal nerve) with ganglia of sympathetic trunk. - Create the conception of grey and white connecting branches in the functional aspect. 3. Basic level of preparation (interdisciplinary integration) of the student includes knowledge of medical biology and histology of the development of nervous system in phylogenesis and ontogenesis. Name of previous disciplines Obtained skills 1. Medical Biology and Histology Know ontogenesis and phylogenesis of nervous system. The structure of the neuron. 2. Sections of Human Anatomy: - osteology The student should have skills to describe the structure of - myology the spine in general, to be able to demonstrate structural features of the cervical vertebrae, their connections with each other and with the bones of the skull. -

Shoulder Anatomy & Clinical Exam

MSK Ultrasound - Spine - Incheon Terminal Orthopedic Private Clinic Yong-Hyun, Yoon C,T-spine Basic Advanced • Medial branch block • C-spine transforaminal block • Facet joint block • Thoracic paravertebral block • C-spine intra-discal injection • Superficial cervical plexus block • Vagus nerve block • Greater occipital nerve block(GON) • Third occipital nerve block(TON) • Hydrodissection • Brachial plexus(1st rib level) • Suboccipital nerve • Stellate ganglion block(SGB) • C1, C2 nerve root, C2 nerve • Brachial plexus block(interscalene) • Recurrent laryngeal nerve • Serratus anterior plane • Cervical nerve root Cervical facet joint Anatomy Diagnosis Cervical facet joint injection C-arm Ultrasound Cervical medial branch Anatomy Nerve innervation • Medial branch • Same level facet joint • Inferior level facet joint • Facet joint • Dual nerve innervation Cervical medial branch C-arm Ultrasound Cervical nerve root Anatomy Diagnosis • Motor • Sensory • Dermatome, myotome, fasciatome Cervical nerve root block C-arm Ultrasound Stallete ganglion block Anatomy Injection Vagus nerve Anatomy Injection L,S-spine Basic Advanced • Medial branch block • Lumbar sympathetic block • Facet joint block • Lumbar plexus block • Superior, inferior hypogastric nerve block • Caudal block • Transverse abdominal plane(TAP) block • Sacral plexus block • Epidural block • Hydrodissection • Interlaminal • Pudendal nerve • Transforaminal injection • Genitofemoral nerve • Superior, inferior cluneal nerve • Rectus abdominal sheath • Erector spinae plane Lumbar facet -

The Peripheral Nervous System

The Peripheral Nervous System Dr. Ali Ebneshahidi Peripheral Nervous System (PNS) – Consists of 12 pairs of cranial nerves and 31 pairs of spinal nerves. – Serves as a critical link between the body and the central nervous system. – peripheral nerves contain an outermost layer of fibrous connective tissue called epineurium which surrounds a thinner layer of fibrous connective tissue called perineurium (surrounds the bundles of nerve or fascicles). Individual nerve fibers within the nerve are surrounded by loose connective tissue called endoneurium. Cranial Nerves Cranial nerves are direct extensions of the brain. Only Nerve I (olfactory) originates from the cerebrum, the remaining 11 pairs originate from the brain stem. Nerve I (Olfactory)- for the sense of smell (sensory). Nerve II (Optic)- for the sense of vision (sensory). Nerve III (Oculomotor)- for controlling muscles and accessory structures of the eyes ( primarily motor). Nerve IV (Trochlear)- for controlling muscles of the eyes (primarily motor). Nerve V (Trigeminal)- for controlling muscles of the eyes, upper and lower jaws and tear glands (mixed). Nerve VI (Abducens)- for controlling muscles that move the eye (primarily motor). Nerve VII (Facial) – for the sense of taste and controlling facial muscles, tear glands and salivary glands (mixed). Nerve VIII (Vestibulocochlear)- for the senses of hearing and equilibrium (sensory). Nerve IX (Glossopharyngeal)- for controlling muscles in the pharynx and to control salivary glands (mixed). Nerve X (Vagus)- for controlling muscles used in speech, swallowing, and the digestive tract, and controls cardiac and smooth muscles (mixed). Nerve XI (Accessory)- for controlling muscles of soft palate, pharynx and larynx (primarily motor). Nerve XII (Hypoglossal) for controlling muscles that move the tongue ( primarily motor). -

Anatomy of Spinal Nerves in the First Turkish Illustrated Anatomy Handwritten Textbook

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by DSpace@HKU Childs Nerv Syst DOI 10.1007/s00381-016-3136-9 COVER EDITORIAL Anatomy of spinal nerves in the first Turkish illustrated anatomy handwritten textbook Murat Çetkin1 & Mustafa Orhan1 & İlhan Bahşi1 & Begümhan Turhan2 Received: 26 May 2016 /Accepted: 30 May 2016 # Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg 2016 BTeşrih-ül Ebdan ve Tercümânı Kıbale-i Feylesûfan^ is the the book, İtâḳî acknowledges the contributions of the Grand first handwritten anatomy textbook with illustrations written Vizier [4, 7]. in Turkish in 17th century by Şemseddîn-i İtâḳî. BTeşrih^ has Not many textbooks about anatomy existed in the Islamic different meanings such as anatomy, skeleton, and cutting a World and the Ottoman Empire until İtâḳî’sbook[9]. In other corpse into pieces [1]. BTeşrih-ül Ebdan ve Tercümânı Kıbale- medical textbooks, anatomy occupies only a few pages in i Feylesûfan ^ means dissection of the body and scholars’ different sections [4]. İtâḳî’s book is a pioneer in its area as birth knowledge [2]. Since this is the first handwritten text- it is written in Turkish, and it is supported with illustrations book in Turkish, it has great importance in the development of [4]. In addition to Turkish, the book contains mostly Arabic medicine in Ottoman Empire. This book was written while and rarely Persian terms as well [4, 6, 7]. Some editions of this Grand Vizier Recep Pasha was in power, and it was dedicated book which was written in the 17th century were reprinted in to the Sultan of that period, Murat the IVth [3, 4]. -

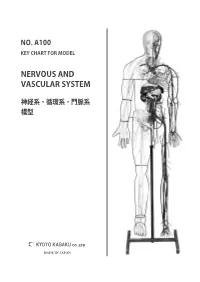

Nervous and Vascular System

NO. A100 KEY CHART FOR MODEL NERVOUS AND VASCULAR SYSTEM 神経系・循環系・門脈系 模型 MADE IN JAPAN KEY CHART FOR MODEL NO. A100 NERVOUS AND VASCULAR SYSTEM 神経系・循環系・門脈系模型 White labels BRAIN ENCEPHALON 脳 A.Frontal lobe of cerebrum A. Lobus frontalis A. 前頭葉 1. Marginal gyrus 1. Gyrus frontalis superior 1. 上前頭回 2. Middle frontal gyrus 2. Gyrus frontalis medius 2. 中前頭回 3. Inferior frontal gyrus 3. Gyrus frontalis inferior 3. 下前頭回 4. Precentral gyru 4. Gyrus precentralis 4. 中心前回 B. Parietal lobe of cerebrum B. Lobus parietalis B. 全頂葉 5. Postcentral gyrus 5. Gyrus postcentralis 5. 中心後回 6. Superior parietal lobule 6. Lobulus parietalis superior 6. 上頭頂小葉 7. Inferior parietal lobule 7. Lobulus parietalis inferior 7. 下頭頂小葉 C.Occipital lobe of cerebrum C. Lobus occipitalis C. 後頭葉 D. Temporal lobe D. Lobus temporalis D. 側頭葉 8. Superior temporal gyrus 8. Gyrus temporalis superior 8. 上側頭回 9. Middle temporal gyrus 9. Gyrus temporalis medius 9. 中側頭回 10. Inferior temporal gyrus 10. Gyrus temporalis inferior 10. 下側頭回 11. Lateral sulcus 11. Sulcus lateralis 11. 外側溝(外側大脳裂) E. Cerebellum E. Cerebellum E. 小脳 12. Biventer lobule 12. Lobulus biventer 12. 二腹小葉 13. Superior semilunar lobule 13. Lobulus semilunaris superior 13. 上半月小葉 14. Inferior lobulus semilunaris 14. Lobulus semilunaris inferior 14. 下半月小葉 15. Tonsil of cerebellum 15. Tonsilla cerebelli 15. 小脳扁桃 16. Floccule 16. Flocculus 16. 片葉 F.Pons F. Pons F. 橋 G.Medullary G. Medulla oblongata G. 延髄 SPINAL CORD MEDULLA SPINALIS 脊髄 H. Cervical enlargement H.Intumescentia cervicalis H. 頸膨大 I.Lumbosacral enlargement I. Intumescentia lumbalis I. 腰膨大 J.Cauda equina J. -

SŁOWNIK ANATOMICZNY (ANGIELSKO–Łacinsłownik Anatomiczny (Angielsko-Łacińsko-Polski)´ SKO–POLSKI)

ANATOMY WORDS (ENGLISH–LATIN–POLISH) SŁOWNIK ANATOMICZNY (ANGIELSKO–ŁACINSłownik anatomiczny (angielsko-łacińsko-polski)´ SKO–POLSKI) English – Je˛zyk angielski Latin – Łacina Polish – Je˛zyk polski Arteries – Te˛tnice accessory obturator artery arteria obturatoria accessoria tętnica zasłonowa dodatkowa acetabular branch ramus acetabularis gałąź panewkowa anterior basal segmental artery arteria segmentalis basalis anterior pulmonis tętnica segmentowa podstawna przednia (dextri et sinistri) płuca (prawego i lewego) anterior cecal artery arteria caecalis anterior tętnica kątnicza przednia anterior cerebral artery arteria cerebri anterior tętnica przednia mózgu anterior choroidal artery arteria choroidea anterior tętnica naczyniówkowa przednia anterior ciliary arteries arteriae ciliares anteriores tętnice rzęskowe przednie anterior circumflex humeral artery arteria circumflexa humeri anterior tętnica okalająca ramię przednia anterior communicating artery arteria communicans anterior tętnica łącząca przednia anterior conjunctival artery arteria conjunctivalis anterior tętnica spojówkowa przednia anterior ethmoidal artery arteria ethmoidalis anterior tętnica sitowa przednia anterior inferior cerebellar artery arteria anterior inferior cerebelli tętnica dolna przednia móżdżku anterior interosseous artery arteria interossea anterior tętnica międzykostna przednia anterior labial branches of deep external rami labiales anteriores arteriae pudendae gałęzie wargowe przednie tętnicy sromowej pudendal artery externae profundae zewnętrznej głębokiej -

Reconstruction of Complex Defects of the Extracranial Facial Nerve: Technique of “The Trifurcation Approach”

European Archives of Oto-Rhino-Laryngology (2019) 276:1793–1798 https://doi.org/10.1007/s00405-019-05418-4 HEAD AND NECK Reconstruction of complex defects of the extracranial facial nerve: technique of “the trifurcation approach” Dirk Beutner1 · Maria Grosheva2 Received: 28 January 2019 / Accepted: 31 March 2019 / Published online: 4 April 2019 © Springer-Verlag GmbH Germany, part of Springer Nature 2019 Abstract Purpose Reconstruction of complex defects of facial nerve (FN) after extensive cancer surgery requires individualized solutions. We describe the trifurcation technique as a modifcation of the combined approach on example of two patients with locally advanced parotid cancer. Methods Due to perineural invasion, extensive resection of the FN from the mastoid segment to the peripheral branches was required. For reanimation of the upper face, a complex cervical plexus graft was sutured end-to-end to the mastoid segment of the FN trunk. The branches of the graft enabled reanimation of three peripheral temporal and zygomatic branches. The mandibular branch was sutured end-to-side to the hypoglossal nerve (hypoglossal–facial nerve transfer, HFNT). Addition- ally, the buccal branch was independently reanimated with ansa cervicalis. Results Facial reanimation was successful in both patients. Good resting tone and voluntary movement were achieved with a mild degree of synkinesis after 13 months. Patient 1 showed the Sunnybrook (SB) composite score 69 [76 (voluntary move- ment score) − 0 (resting symmetry score) − 7 (synkinesis score)]. In patient 2, the SB composite score was 76 (80 − 0 − 4, respectively). Conclusions In this trifurcation approach, cervical cutaneous plexus provides a long complex nerve graft, which allows bridging the gap between proximal FN stump and several peripheral branches without great expenditure. -

The Anatomy of Spinal Nerves in the “Teşrihü’L-Ebdan Min E’T-Tıb” Written in the Fourteenth Century* XIV

The anatomy of spinal nerves in the “Teşrihü’l-Ebdan Min e’t-Tıb” written in the fourteenth century* XIV. yüzyılda yazılmış olan “Teşrihü’l-Ebdan min e’t-Tıb” adlı eserde spinal sinirlerin anatomisi İlhan Bahşii, Mustafa Orhanii, Murat Çetkiniii iMD, PhD. Department of Anatomy, Faculty of Medicine, Gaziantep University https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8078-7074 iiProf. Dr. Department of Anatomy, Faculty of Medicine, Gaziantep University https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4403-5718 iiiPhD. Department of Anatomy, Faculty of Medicine, Istanbul Medeniyet University https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6676-9005 ABSTRACT Considering that the visual dimension of anatomy cannot be ignored and an anatomy education without the visual part will make a doctor imperfect in their profession, it may be seen that pictorial anatomy books written in previous periods are highly valuable. The purpose of this study is to investigate the spinal nerve anatomy included in the work titled Teşrihü’l-Ebdan min e’t-Tıb written in the XIVth century and compare the information at that period to the information of our time. The nervous system was analyzed under a separate title in the book. Firstly, general information was provided about nerves, and then cranial and spinal nerves were described. The author stated in his work that there are two differences between humans and animals as feeling and movement. He stated that the center for feeling and movement is the brain and all nerves converge in the brain. Although there are insufficient or incorrect information in historical books of medicine, such books are highly valuable as they show the scientific progress. -

Comparative Study of Superficial Cervical Plexus Block and Nerve of Arnold Block with Intravenous Antiemetic Drugs Dexamethasone

Comparative Study of Superficial Cervical Plexus Block and Nerve of Arnold Block with Intravenous antiemetic drugs Dexamethasone and Ondansetron and Incidence of Post-operative Nausea Vomiting for Inner Ear Surgery Indiana University School of Medicine Riley Hospital for Children Principal Investigator: Malik Nouri, MD Co Investigator: Charles Yates, MD Version 2.0 Date: 01/27/2017 Page 1 of 12 Table of Contents: Study Schema 1.0 Background 2.0 Rationale and Specific Aims 3.0 Inclusion/Exclusion Criteria 4.0 Enrollment/Randomization 5.0 Study Procedures 6.0 Reporting of Adverse Events of Unanticipated Problems involving Risk to Participants or Others 7.0 Study Withdrawal/Discontinuation 8.0 Statistical Considerations 9.0 Privacy/Confidentiality Issues 10.0 Follow-up and Record Retention 11.0 Analysis of Results Page 2 of 12 1.0 Background Patients that undergo inner ear surgery often complain of postoperative nausea and vomiting (PONV) despite prophylactic antiemetic regiments with 5HT3 antagonists, steroids and vigorous hydration. Patients still experience this unpleasant feeling that may prolong hospital stay and can lead to nutritional issues such as dehydration and huge patient and family dissatisfaction. We would like to explore the use of regional anesthesia and potential antiemetic proprieties and compare it’s efficacy to the existing therapy. PONV is an unpleasant complication following anesthesia, it is well known that patients undergoing certain surgical procedures such as those involving the inner ear, the tympanomastoid cells, and the cochlear organ may be more prone to PONV. This complication can be anticipated in those instances and prophylactically treated with antiemetics, Vigorous hydration and cautious selection of anesthetic technique and avoidance of drugs known to promote nausea1, 2, 3. -

Morphology and Histology of the Testicle. Spermiogenesis

Morphology and histology of the testicle. Spermiogenesis. Ph.D, M.D. Dávid Lendvai Anatomy, Histology and Embryology Institute 2019. Michelangelo Buonarotti: David, 1501. OVERVIEW OF THE MALE GENITAL TRACT TESTICLES - FUNCTIONS • Germ-cell production (Convoluted semiferous tubules): Spermiogenesis Spermiohistogenesis • Testosteron production (Leydig-cells): secondary gender characteristics spermiogenesis sexual activity (Libido) anabolic effect male behaviors TESTICLE •Left is usually larger and it has a lower position in the scrotum •45º inclined forward •2 side surfaces : Facies med. Facies lat. •2 margins : Margo ant. (free) (4) Margo post. (with epididymis=6 together) (3) •2 Poles: Extremitas sup. (1) Extremitas inf. (2) 1 Extremitas sup. 2 Extremitas inf. 3 Margo post. 4 Margo ant. 5 Mesorchium 6 Epididymis 7 A. testicularis, Plexus pampiniformis 8 Ductus deferens TESTICLE - STRUCTURES Tunica vaginalis testis = •Visceral lamina (Epiorchium) •Parietal lamina (Periorchium) between: Cavum serosum scroti Mesorchium Appendix testis (hydatid of Morgani) = cranial end of Müllerian duct STRUCTURES OF THE TESTIS AND EPIDIDYMIS DUCTS OF THE TESTIS AND EPIDIDYMIS HISTOLOGY OF THE TESTIS AND EPIDIDYMIS overview HISTOLOGY OF THE TESTIS AND EPIDIDYMIS HISTOLOGY OF THE TESTIS AND EPIDIDYMIS HISTOLOGY OF THE TESTIS AND EPIDIDYMIS SPERMATOGENESIS • The Convoluted Seminiferous Tubules • These tubules are enclosed by a thick basal lamina and surrounded by 3-4 layers of smooth muscle cells (or myoid cells). The insides of the tubules are lined with seminiferous epithelium, which consists of two general types of cells: spermatogenic cells and Sertoli cells. • Spermatogenic cells: Spermatogoniaare the first cells of spermatogenesis. They originate in the 4th week of foetal development in the endodermal walls of the yolk sac and migrate to the primordium of the testis, where they differentiate into spermatogonia.